12 January 2024. Post Office [3] | Mars

The Post Office, the government, and being better ‘guardians’ // We’re not going to be living on Mars any time soon. [#532]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: The Post Office, the government, and the ‘guardian’ syndrome

This is the third of three posts on the UK Post Office scandal. The first was on how the Post Office was able to bully its sub-postmasters, and the second about corporate governance in the Post Office. This third post is about the Post Office and the government, and the deeper meaning of the scandal.

The lawyer who blogs as ‘Cyclefree’ suggested earlier this month that the Post Office’s misdemeanours over Horizon were a familiar UK story. We have seen them before over the last 60 years, in how the National Coal Board behaved over the Aberfan disaster, by the police after the Hillsborough tragedy, by the NHS in multiple medical scandals, by the British government in the blood contamination scandal and over Windrush. She didn’t mention it, but the Australian robodebt scandal has similarities, even if that was more ideologically driven.

The details differ in each case, but the pattern of misbehaviour by those with power is “so very similar”. She lists:

– the refusal to listen to concerns

– the lies and cover ups

– the stingy callous approach to apologies and compensation

– the refusal to accept responsibility

– the avoidance of accountability.

At the core of this, there are two repeating behaviours:

The first is the arrogance of indispensability. It is this which leads to the abuse of power which lies at the heart of the actions taken. The Post Office’s conduct over nearly two decades might best be described as a rampage of extortion with menaces, based on lies.

And the second?

It is an indifference to ordinary people, to the human consequences of misbehaviour, to the impact on others. [Her emphasis].

One way to think about this is through the lens of Jane Jacobs’ book Systems of Survival. It’s an odd book, written as a set of dialogues between fictional members of a study group, but it concludes that human societies work on two systems or ‘syndromes’. One is based on territory (‘Guardians’) and the other is based on exchange (‘Traders’).

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

I blogged about the book here, and should nod towards Victoria Ward, who introduced me to it.

When things go wrong, it is either because people in a syndrome are over-zealous, or because people in one syndrome are behaving in a way that belongs to the other.

There’s a list in the book of 15 principles for each of the two syndromes, and an explanation of how she arrived at them. The 15 Guardian principles, for example, include:

Be Obedient and Disciplined

Adhere to Tradition

Respect Hierarchy

Be Loyal

Shun trading

My suggestion here is that the Post Office, and the Royal Mail, are both Guardian organisations. I know they sell things, but they are there in different ways to support the state. The state monopoly on the post was created by an Act of Parliament in 1657, in the dog days of the Commonwealth, and the first Postmaster-General was appointed by Charles 1 in 1661. The picture of the monarch on the stamps is also a clue here, along with the fact that the Post Office has its own right of prosecution.

Guardian organisations go wrong in two ways. The first is that they ape traders, which leads to personal corruption. The second is that they become over-zealous versions of themselves. That’s what seems to have happened here. We see this in the language used by investigators, the bonuses they were paid for successful prosecutions, and by the fatal lack of a distinction in the internal prosecution process between investigation and assessment of the case—as in Jarnail Singh’s dismal emails, for example.

HM Customs, another ‘Guardian’ organisation that used to have the right in-house to prosecute, lost it as a result of breaching normal procedures and disregarding the law.1

And we also see it in the hierarchical culture, where everyone inside the Post Office stayed in line, asked no questions, and repeated the same myths about Horizon when asked about it:

Among both its management and audit team at the time... there was a hierarchical culture in which criticism was not welcomed... Despite individual appeals by sub-postmasters, Post Office managers did not challenge the leadership or organisation, and apparently believed their systems, including Horizon, were infallible.

Or, as the Post Office told BBC South in 2011. In 2011!

"The Horizon computer system is absolutely accurate and reliable".

That’s only half of the story, though. The other thing that was happening, throughout this story, was a desire by governments first to privatise the Royal Mail, and, from 2012, to reduce the losses being made by the now independent Post Office. This seems to be why Paula Vennells, with her retail background, was appointed Chief Executive. Her objective, set by the government, was to get to breakeven.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

It’s overlooked, but she achieved this goal, even if she did it partly by cutting payments to sub-postmasters, and partly through sell-offs and co-location deals that meant it was hard—while banks were closing branches—to be strategic about using the Post Office to ensure some basic level of local financial services provision. This is probably the rationale for the misjudged award of Vennells’ CBE in 2019.

If that’s one part of the process of hollowing out the capacity of the state, the other part was in the IT contracts. It’s sometimes forgotten that Post Office engineers built the first computer in the world, as part of the UK war effort at Bletchley Park.

As Helen Margetts of the Oxford Internet Institute writes at The Conversation, Britain had become, over the ‘80s and ‘90s, a “global leader in procuring the ‘mega-IT contract”. This didn’t mean that it got good at it, however:

Over the years, government departments in the UK stopped innovating with technology, and have started contracting it all out to computer services providers... During this period, the National Audit Office (NAO) produced a stack of politely damning reports on government IT outsourcing – about cost overruns, failed projects, error-ridden systems and troubled contract relationships.

In the case of the Horizon proposal with Fujitsu, Geoff Mulgan recalls being asked to look at it when he was working in Downing Street in the late-90s. (He was called to give evidence to the Public Inquiry because his memos turned up). He had, at the time, recommended cancellation.“It was,” he says, “obvious that poor decisions were being made”

There were two particular flaws, as he said in his testimony:

It was insane that politicians were having to make judgements about complex technical and business issues, far beyond their competence or experience. In this particular case the design of the PFI meant that the post office in general and sub-postmasters in particular played no role in designing the system.2

The government insists that it merely sets objectives for the Post Office. It says the organisation

"operates as an independent, commercial business within the strategic parameters set by government.”

The evidence says otherwise. This piece is already too long, so let one piece from Nick Wallis’ coverage stand for the whole. In 2020, he asked a senior Post Office insider about it:

(T)hey nearly spat out their drink with laughter. The insider told me that whilst they were there, Post Office staff with varying levels of seniority were running in and out of BIS (the relevant government department) the whole time. They also told me that culturally, within the Post Office, senior management priorities revolved around what the government wanted. What the government wanted, I was told, to the exclusion of almost anything else, was for the Post Office to become profitable.

And it seems clear from some accounts that the government’s target that the Post Office break even—which is also likely to have been a factor in their bonus payments—was not far from their minds around the Boardroom table as they were trying to avoid paying compensation to those they had wronged. Be careful what you wish for: the provision for compensation in the Post Office accounts is currently £244 million.

The ITV drama has had the effect of accelerating both the legal process to reverse the unsafe convictions, and of paying compensation. Paula Vennells has at last returned her CBE. There is, not before time, some scrutiny of Fujitsu’s role in all of this. Former government ministers are busy covering their backs.3 These are all welcome outcomes.

But even though the Post Office has a new Chief Executive, a new Chairman, and a new Board, which includes sub-postmasters for the first time, it is still behaving in the same entitled ways.

The legislation that created the independent Post Office in 2012 includes a mechanism to turn it into a mutually owned organisation. I suspect that the only way for the Post Office to regain trust is to do this: to become a mutual, with proper public objectives about serving our communities. To be a proper Guardian, in other words.

(Sub-postmasters at the Royal Courts of Justice after the first appeals were upheld. Source: Hudgell Solicitors.)

2: We’re not going to be living on Mars any time soon

When Jim Dator was still teaching futures students in Hawai’i, one of the exercises that he set them was to take a blank sheet and design some governance systems for a human colony on Mars.

I felt my undergraduate students were becoming too conventional and uncreative... Finally, in the early 1980s, I said, "Well, forget about Earth and its political history. Let’s go to Mars. Let's design for a settlement there. Almost everything on Mars is different from Earth. So just leave your Earthly baggage at home and let's start afresh."

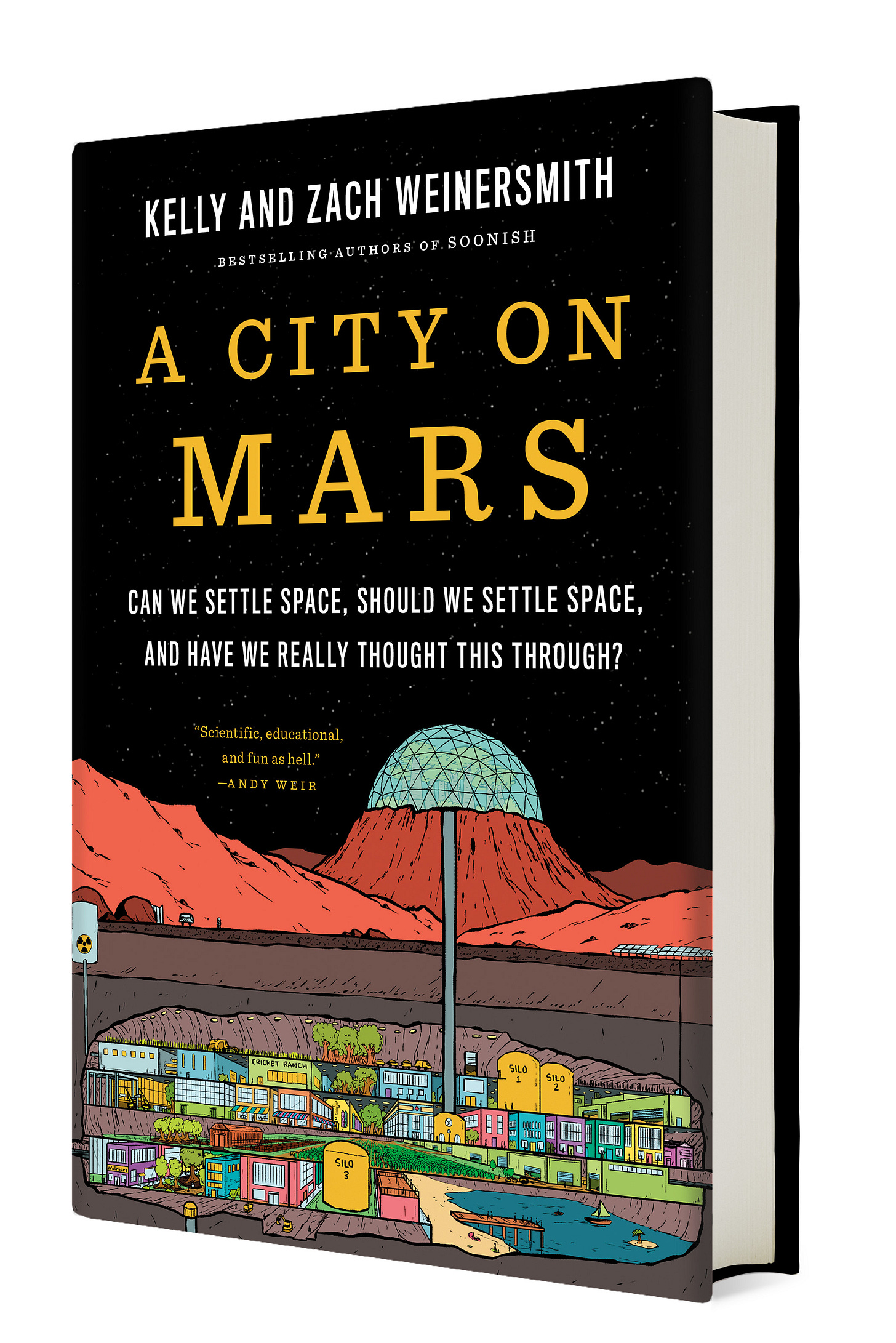

As a teaching device this seems to have worked. And it was what I was reminded of when I saw a long piece by Cory Doctorow about the recent book A City on Mars, by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith.

(Source: A City On Mars.)

She is an ecologist, and he’s a cartoonist. They’re married. Their last book, which I missed but looks great, was called Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That’ll Improve And/Or Ruin Everything.

Anyway, what they set out to write was a book about the governance of space colonies, since there are lots of people who keep telling us that these are just around the corner. What they found was that no-one’s going to be living in a space colony any time soon. I’ll let Cory Doctorow pick up the story:

The Weinersmiths make the (convincing) case that every aspect of space settlement is vastly beyond our current or reasonably foreseeable technical capability. What's more, every argument in favor of pursuing space settlement is errant nonsense. And finally: all the energy we are putting into space settlement actually holds back real space science, which offers numerous benefits to our species and planet (and is just darned cool). (His emphasis.

The reason for the first issue is that anywhere that we might feasibly land in space is grimly inhospitable—far more so than Earth, and more so even than an Earth with several more degrees of warming.

Mars is covered in poison and the sky disappears under planet-sized storms that go on and on. The Moon is covered in black-lung-causing, razor-sharp, electrostatically charged dust. Everything is radioactive. There's virtually no water. There are temperature swings of hundreds of degrees every couple of hours or weeks.

There’s also never going to be a business case in which it is cheaper to extract minerals from other planets, or steroids, or whatever, than it is to make them or extract them on earth. Nor will space save us from the climate emergency:

The unimaginably vast trove of material and the energy and advanced technology needed to lift it off Earth and get it to Mars is orders of magnitude more material and energy than we would need to resolve the actual climate emergency here.

And the whole business of colonies in space needs a lot of people to be living in these colonies, if it is going to work.

The number of humans you need in a colony to establish a new population is hard to estimate, but it's very large. Larger than we can foreseeably establish on the Moon, on Mars, or on a space-station. But even if we could establish such a colony, there's little evidence that it could sustain itself – not only are we a very, very long way off from such a population being able to satisfy its material needs off-planet, but we have little reason to believe that children could gestate, be born, and grow to adulthood off-planet.

Finally, it’s worth just mentioning space law, the subject that started the Weinersmiths down this track in the first place. There’s lots of noise from space entrepreneur types that when they land on an asteroid they’ll definitely just say it’s theirs, but space law is both real and enforceable:

Not only would any space settlement be terribly, urgently dependent on support from Earth for the long-foreseeable future, but every asteroid miner, Lunar He3 exporter and Martian potato-farmer hoping to monetize their products would have an enforcement nexus with a terrestrial nation and thus the courts of that nation.

It’s worth saying that the Weinersmith’s aren’t anti-space. They just want us, as a species, to do it properly. Because sending people out into space and landing them on anything is mind-bogglingly expensive. You can do a lot of space science for the same amount of money.

For the price of a crewed return trip to Mars, you could put multiplerobots onto every significant object in our solar system, and pilot an appreciable fleet of these robot explorers back to Earth with samples. For the cost of a tiny, fraught, lethal Moon-base, we could create hundreds of experiments in creating efficient, long-term, closed biospheres for human life.

(Future astronauts hard at work on the moon. Source: NASA

Because, for example, if we are ever going to have sustainable human colonies in space, we’ll have had to learn how to create credible ecosystems in space first. So we’d need first to learn how to breed animals, and probably insects as well.

It’s a long piece, so I’m going to let you go into the detail yourselves, but Doctorow suggests that the important part of space science is what we learn from it for improving outcomes here on Earth:

If we can figure out how to extract resources as dispersed as Lunar He3 or asteroid ice, we'll have solved problems like extracting tons of gold from the ocean or conflict minerals from landfill sites... If we can build the robots that are necessary for supporting a space society, we will have learned how to build robots that take up the most dangerous and unpleasant tasks that human workers perform on Earth today.

Settling space, in other words, is really hard: much, much, harder than solving problems on Earth. But doing science in space can really help us to solve those problems. And we need all the help we can get.

j2t#532

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

A 1997 prosecution brought by Customs led to a trial that was halted by the judge because of a “catalogue of flawed procedures, misleading requests, illegalities and incompetence at a number of levels.” It sounds familiar. There were two independent inquiries into separate failed Customs’ prosecutions that MPs discussed in the House of Commons.

Eleanor Shaikh has written more than you are ever likely to want to know about the early days of Horizon.

Ed Davey, for example, who was Minister for Postal Affairs from 2010 to 2012 and says the Post Office misled him. Computer Weekly published seven serious stories about the scandal between 2009 and 2012. He could have asked a researcher to read them rather than relying on the old boys’ club.