10 January 2024. Emissions | Post Office [2]

Giving up on 1.5 degrees // The Post Office’s closed belief system and failed culture

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Giving up on 1.5 degrees

There’s a short, sharp and depressing New Year message at the Energy Central site written by Tony Paradiso. It suggests that our collective New Year’s Resolution should be stop deluding ourselves that we’ll be able to keep the increase in global warming to within 1.5 degrees:

We can only hope that going beyond that limit doesn’t permanently damage the environment, because beyond it we will go.

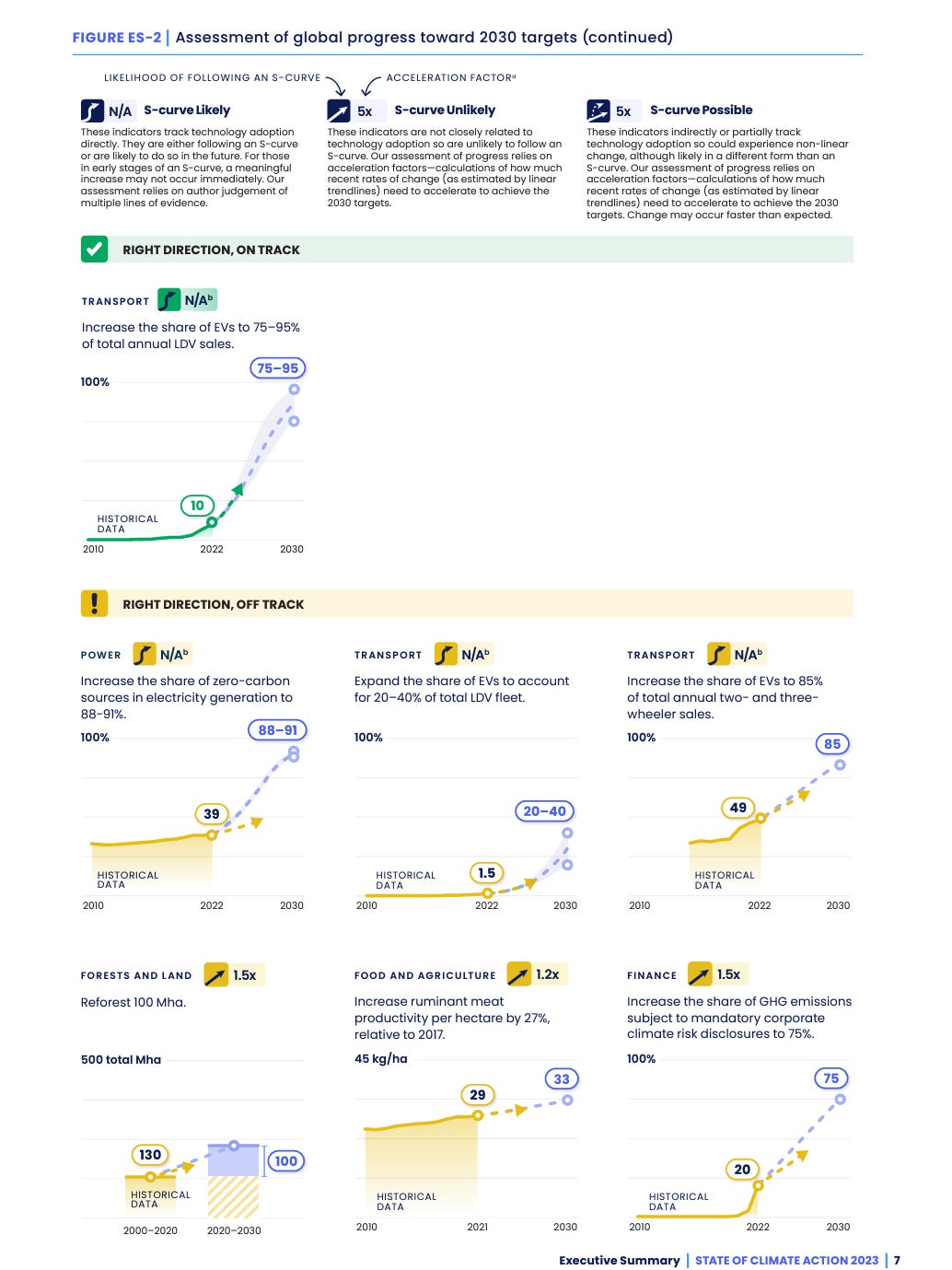

He’s come to this conclusion from reading the World Resources Institute’s State of Climate Action 2023 (long pdf) report, which came out in November. The report includes 42 benchmarks of climate change progress. Of the 42, one of these is on track, which is the progress towards electric vehicles. Six of them are going in the right direction, but are off track. The report describes these as “promising but insufficient”:

These include zero-carbon electric generation, EV fleet metrics, ruminant meat productivity, reforestation, and the percentage share of global GHG emissions under mandatory corporate climate risk disclosure.

(Well performing climate indicators. Source: World Resources Institute.)

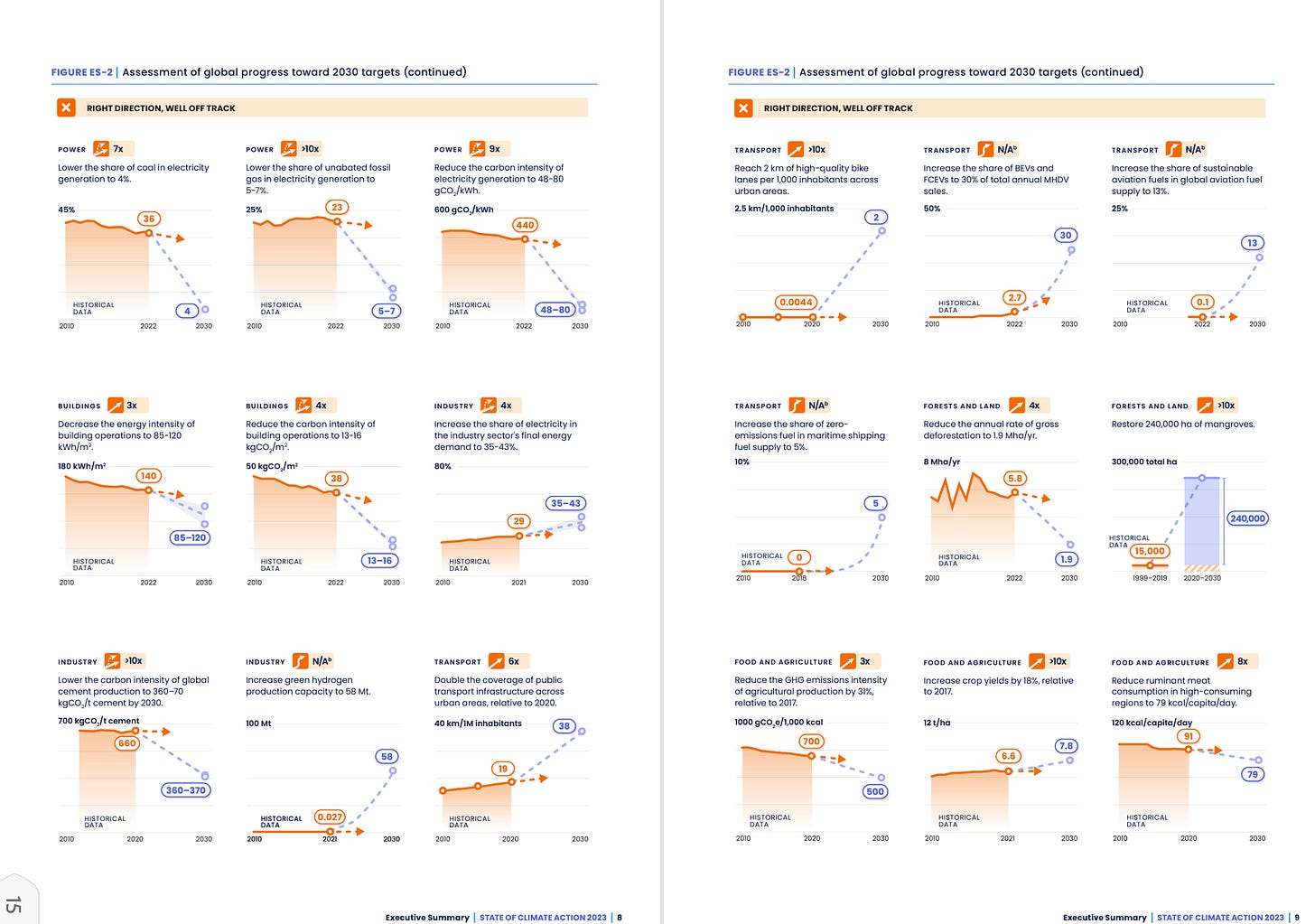

So that leaves another 35 benchmarks. Of these, 24 are are going in the right direction, but are way off track (“well below the required speed”), and six are going in the wrong direction, and so need a U-turn. These include the carbon intensity of steel; the percentage of trips travelled in private cars; the proportion of buses that are electric powered; reducing the rate of annual loss of mangrove; “reducing the share of food production lost” (yes, this is unclear to me as well); and phasing out financing for fossil fuels, including public subsidies.

The last five can’t be measured because there isn’t enough data.

(A selection of poorly performing climate-related indicators. Hint: look at the difference between the orange lines and the dotted lines. Source: World Resources Institute.)

Looking at this whole dashboard, on pages 6-11 of the State of the Climate 2023, Paradiso concludes:

1.5 degrees C was a worthy and perhaps a necessary goal. However, at this point it’s unachievable. The rationale response: reassess and realign your goals. I’d start by using the 42 metrics to conduct a “post-mortem.”

The reason he’s pessimistic is that we don’t have much time to stay inside the carbon budget for 1.5 degrees and—I’m reading between his lines here, but only slightly—the things that need to change will change too slowly:

Here’s the reality: financing levels will invariably fall short of desired targets. Fossil fuels will not be quickly phased out. And because of insufficient grid infrastructure investments, even clean power generation isn’t likely to reach its longer-term targets.

He argues that the the two main roadblocks are the need to build the necessary infrastructure and the need fundamentally to change behaviour. Infrastructure change takes decades and substantial investment.

You can argue with some of this, of course. There’s a reasonable volume of research out there that says that the infrastructure question is largely a question of political will, because globally we already spend a lot of money on new infrastructure, and the marginal cost of channelling that into transition infrastructure is only a few percentage points of GDP.

People like Tim Benton, the food expert, think that behaviour change could come quite quickly when people realise how stark the effects of global warming are and how little their political leaders are doing. I quoted him to this effect in a piece here a couple of months ago:

the combination of the costs of the current system, and events triggered by crises in the current system, could well drive this systemic change. As Tim concluded, “The politics will change as the world changes.”

The World Resources Institute isn’t quite as Panglossian about 1.5 degrees as Paradiso suggests. They acknowledge that the window is closing fast, and that it will take urgent action by political leaders. I’d say that it’s this bit that is the real problem, since our political leaders seem to be over-attached to fossil fuel interests. (This is even true of those politicians who don’t think that climate change action is a form of culture war).

They also note that some of the technologies in their list could potentially hit rapid growth through combinations of economies of scale and scope, even if they are off track at the moment.

But all this does raise interesting questions about the politics of 1.5 degrees. This was reviewed in an article in Scientific American in 2022, ahead of the COP in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022. Its assessment was that few scientists thought it likely that we would stay below 1.5 degrees. Indeed a UNEP report in 2022 found that

there is “no credible path” to 1.5 C.

And in 2021 Nature polled anonymously the scientists who had contributed to that year’s IPCC report, who had a similar view:

Out of the 92 anonymous respondents, the vast majority expected the world to warm by more than 1.5 C by the end of the century. Sixty percent of them predicted warming of at least 3 C.

Some scientists didn’t want to say this publicly while there was still a possibility, even an unlikely one, of staying within the target. And even if we do pass 1.5 degrees, it could be decades before we know this for sure.

Others were reluctant to say so because of the political effects this might have on campaigns for climate action:

there are concerns that publicly declaring it a failure could dampen global climate action. Once the world has missed a major target, it could become easier for some people to simply give up. It’s critical to communicate that a missed target necessitates greater urgency, not less, and that every bit of additional warming that’s prevented makes a difference to the world.

Some look at the possibility of temporarily passing 1.5 degrees and then pulling it back again, although this would involve “negative emissions” technologies, finding ways of sucking emissions out of the atmosphere. With this—apart from the largely unproven, or unknown, technologies—you get into questions of how far you might overshoot 1.5 degrees or how long you are allowed to overshoot for. But most models that see us staying within 1.5 degrees involve some kind of negative emissions.

(Non-violent action by Scientist Rebellion, 2022. Source: Scientist Rebellion)

At the same time, there are also groups of scientists who think the politics of this work differently. There’s an open letter on the Scientist Rebellion site that says that effective climate action is being blocked by vested interests, and that it’s only by being honest about this that we’ll get the political mobilisation that we need:

Overcoming these vested interests requires a large-scale mobilisation of society. It has happened before: without strong social movements, there would be no civil rights, no women’s right to vote, no weekends, no holidays, nor much of the welfare that considerable parts of the world enjoy today. And it can happen again: citizens in the Netherlands recently forced their government to plan a phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies, while people in Ecuador prevented oil extraction in the Amazonian Yasuni National Park.

2: The Post Office’s closed belief system and failed culture

In the first part of this post, I wrote about the history of the UK Post Office scandal and the reasons the Post Office was able to bully and victimise their sub-postmasters. Although this story has moved on faster than I could have imagined at the weekend, there’s not enough attention being paid to the corporate culture in the Post Office that led to this behaviour. (This seems to extend, by some accounts, to the way the Post Office is currently treating the Statutory Public Inquiry.)

It takes a certain type of corporate culture to keep on doing things in the face of mounting evidence that they are the wrong things to do. A corporate culture, in other words, with “no reasonable doubt”, in the memorable phrase of the management academic Charles Handy.

(Reasonable doubt. Source: Pofoshop, Etsy)

This lack of reasonable doubt seems to have come from two beliefs inside the organisation. The first is the idea of “technological infallibility”, and the second was the idea that the Post Office brand needed protecting at all costs. Combining this creates a belief system that:

(1) the losses were real, not fictional;

(2) it was bad for the Post Office’s reputation if people thought that sub-postmasters were dishonest; and

(3) they therefore needed to be prosecuted. Because the Post Office also had the right to conduct its own prosecutions, this quickly turned into a grim vicious cycle.

The idea of “technological “infallibility” comes up in the article in The Conversation that I quoted in the first part of this. The researchers write:

This... factor is particularly pertinent for disputes around technology, in which people can easily fall prey to what researchers call “automation bias”, a psychological bias in which people readily discount information that does not conform to what technology advises or has determined.

You also see it in witness statements by accused sub-postmasters about their interaction with the Post Office auditors. Nicola Arch recalls:

(The auditor said) ‘You popped it in your purse.’ I said: ‘No, I didn’t.’ I told him the daily totals were right and I had evidence to show that, but I couldn’t access it. And he replied that he was not interested in what I said as the computer was the most hi-tech equipment you could wish for.

The notion of “protecting the brand” also ran deep through the culture. The ITV drama has a court-room scene (I’m assuming that this is from a court transcript) in which Angela van den Bogerd, in the witness box, states this as a rationale for the policy. She had at that point been with the Post Office for 30 years, she was a Director, and she had been central to the Horizon process and the investigations since 2010. The judge stops her and asks her to explain what this means.

At this point we need to back up a bit, because some of the messy corporate history of the Post Office is relevant.

When all of this starts, and Horizon is rolled out in 1999, the Post Office is a division of the Royal Mail, which at that stage was a publicly owned corporation. The Royal Mail was mostly privatised in 2011 (and fully privatised in 2015), and you may have your own views of the efficacy of that, given that it runs the UK’s universal postal service. The same legislation created the Post Office as an independent entity which was wholly owned by the government, as from April 2012.

Paula Vennells, who had joined the Post Office in 2008 as Group Network Director, from a private sector background—Unilever, Argos, Whitbread, Dixons, etc— became the chief executive of the newly formed organisation.

In the summer of 2012, under pressure from MP James Arbuthnot, one of the good guys in the story, Vennells agreed to fund an independent investigation by Second Sight into the claims by the sub-postmasters that their losses had been caused by the Horizon system. Second Sight was, and is, a specialist financial fraud investigation company. It issued an interim report in 2013, and two further briefing reports in 2014 and 2015.

(Second Sight’s interim report)

Second Sight was only able to get so far, and there’s some evidence that Fujitsu actively sought to mislead them. All the same, even their interim report raised enough questions to cause doubts. Enough anyway, for the Post Office to propose a mediation scheme. (It then sabotaged this, but that’s a different part of the story.)

It’s hard to read up on this without thinking—and this is the kindest interpretation—that Paula Vennells was a long, long way out of her depth as CEO, and that the governance structures of the Post Office were missing in action. As a separately constituted business the Post Office had a a non-executive Chair, appointed by the government, and a number of independent non-executive directors, including—always—one non-executive director nominated by the government.

As Investopedia explains, non-executive directors are supposed to keep the Board accountable, by raising issues of performance, strategy, and risk, either formally or informally. As the Corporate Governance Institute says,

An effective non-executive director is not a person who is there on behalf of the CEO as a box ticker and ‘yes’ person.

You always need to distinguish what was known at the time from what we have learned later, but these are some of the things that were known in 2013 that ought to have raised big flags for the non-executive directors:

The initial Second Sight reports didn’t find evidence of “systemic problems” with Horizon, but they found plenty of examples of faults that produced phantom losses.

The Post Office’s internal management information systems were terrible, as a 2013 report identified. As journalist Nick Wallis says:

the Post Office had no real control over its internal accounting systems for the duration of its Horizon-related prosecution spree... and so it didn’t know where money was going, nor could it properly account for where it came from.

In 2009 Accountancy Age had covered the Horizon issue and made a specific editorial recommendation that “The Post Office should consider an IT audit to show it has taken the matter seriously. “

In 2011, the Post Office’s auditors, EY, had advised it “that the Post Office and Fujitsu did not apply normal, basic management controls over the testing and release of system changes.” (These two points from James Christie’s blog.)

Sub-postmasters were highly vetted people who were subject to “good character” checks before they were appointed. The idea that there was a large and sudden increase in criminality after Horizon was rolled out was implausible. The prosecution rate post-Horizon jumped from 2 or 3 a year to 50 or 60, and no-one appears to have asked why this was.

No-one seems to have raised a question of risk—that if the prosecutions turned out not to be safe, the consequences for the Post Office would be reputationally and financially catastrophic. Yet Second Sight had already found a Post Office investigator’s report, written prior to the prosecution of Jo Hamilton in 2006, that said “I was unable to find any evidence of theft or that the cash figures had been deliberately inflated."

And Alan Bates, who ran the Justice for Sub-postmasters Alliance (JSA) had raised the possibility of this risk in 2012 with then then Minister for Posts, Ed Davey, in an email that said “the accounting scandal could leave taxpayers exposed to "astronomical" costs.”

No-one senior seems to have properly interrogated the critical question of whether it was possible to access the sub-postmasters’ accounts remotely through Horizon until Vennells and van den Bogerd were called in front of the Business Affairs’ Select Committee in 2015.

In fact, both the ITV drama series and the accompanying documentary made quite a lot—rightly—of an internal email from Vennells to senior colleagues, including van den Bogerd, ahead of the 2015 Select Committee hearing. This was found during the discovery process for the civil cases that the JSA launched against the Post Office in 2018. Vennells wrote in the email:

"Is it possible to access the system remotely?"

Underneath, she has written: "What is the true answer? I hope it is that we know it is not possible and that we are able to explain why that is. I need to say no it is not possible and that we are sure of this because of xxx (sic) and we know this because we had the system assured.".

In short, at least on the face of it, the lack of both situational awareness and curiosity is staggering. It’s possible that non-executive directors raised these points, but were ignored. It seems unlikely. As far as I can see, none of them have come forward to say so, and Alice Perkins, who was Chair from 2012 to 2015, has declined the opportunity to be interviewed about it.

And what we know from piecing together the court evidence the Post Office has provided (this is mostly down to the work of Nick Wallis) is that although in 2012 Perkins instigated the process that led to the Second Sight investigation, after that the non-executives, including the government representatives, were actively involved in Board decisions which were about watering down the mediation scheme and trying to block compensation payments.

It probably doesn’t “go all the way to the top”, but the British government is deeply implicated.

j2t#531

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The FT published a piece on Horizon yesterday that included this line: "The show does make some disparaging references to the British state, which owns the Post Office. But that state is not so much a dark, controlling force as a quagmire."

I think you're right to note that the PO's inability to effectively frame and evaluate experiences outside of its accepted scripts was a major issue here. It was a scandal of ineffective processing as much as deliberate evil.

https://www.ft.com/content/c7a4f51a-994e-4e73-83a9-8ef9faf97fa5?shareType=nongift