24 November 2023. Food | Culture

Breaking the industrial food system // The Romantic movement and the revolt against technology [#518]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Sorry to miss the post on Wednesday—pressure of work! Have a good weekend.

1: Breaking the industrial food system

I was at an AFN meeting (Agri Foods for Net Zero) this week which was a follow up to the scenarios work that I did earlier this year (more about that here).

Most of it was designed to develop the group’s research agenda, which is about accelerating the transition to Net Zero, and most of it was unattributable.

But Tim Benton, of Chatham House and Leeds University, opened with short presentation on the “triple lock in” that is shaping the food sector in ways that are quite destructive.

Quite destructive? Three measures of that. We’re currently producing enough to feed the world’s population, but close to one-in-ten people globally are under-nourished, and this number has been increasing again after a long period of decline. 770 million—also close to one-in-ten of the world population—are obese. The FAO has recently estimated that the external health costs of the food system are at least $10 trillion annually:

The report found that the biggest hidden costs, more than 70 percent, are driven by unhealthy diets that are high in ultra-processed foods, fats and sugars, leading to obesity and non-communicable diseases, and causing labour productivity losses. This is particularly the case in richer countries. One fifth of the total costs are environment-related, from greenhouse gas and nitrogen emissions, land-use change and water use, with all countries affected.

There are also hidden costs associated with poverty and under-nourishment, especially in poorer countries, but there are also, in richer countries, lost opportunities and lifetime health costs caused by hunger in childhood. (The FAO’s full report is here.

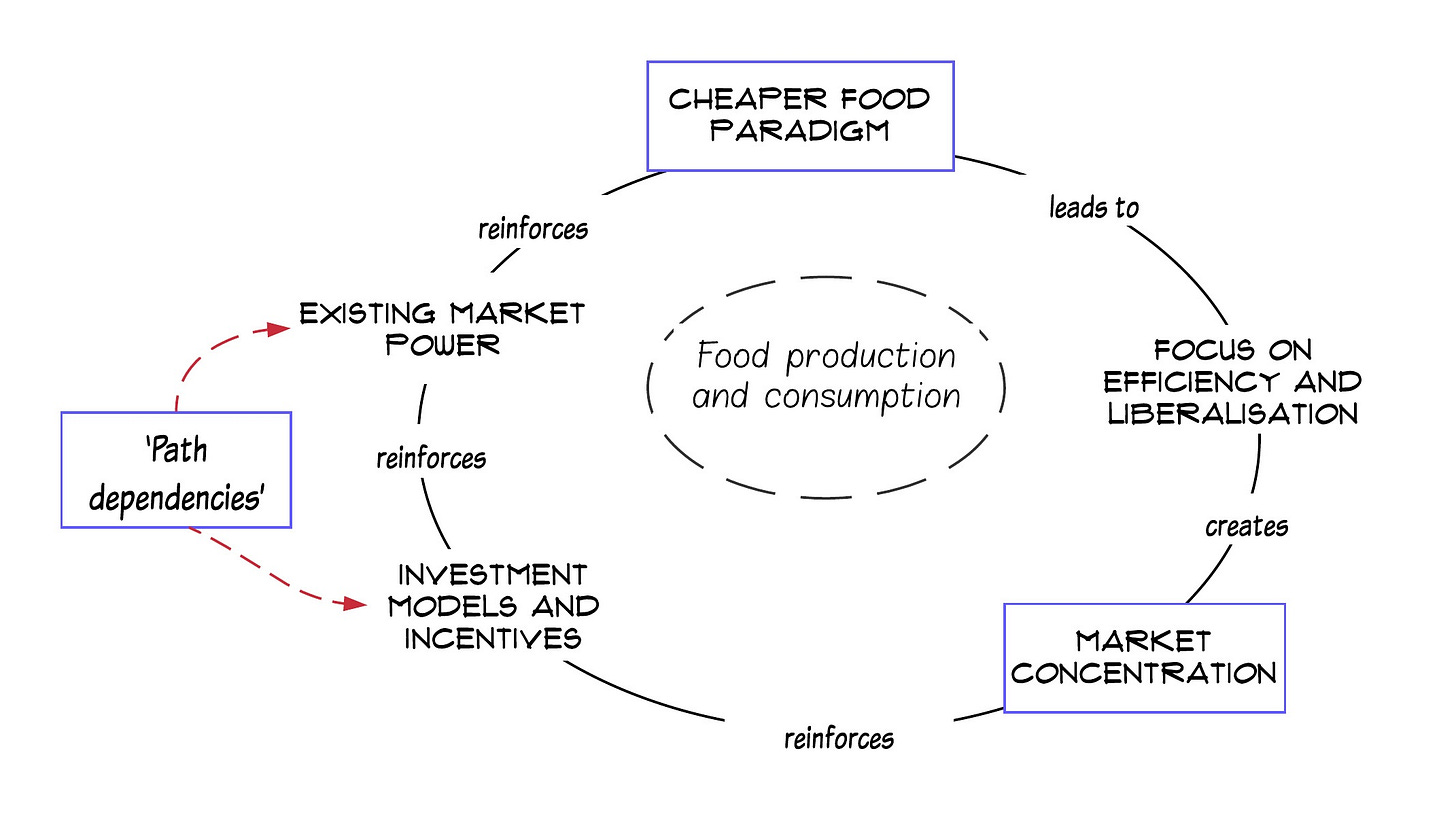

Benton basically summarised three lock-ins, which are inter-connected:

The cheaper food paradigm

Market concentration

Path dependencies

In some ways the first of these drives the rest of the system, through the assumptions that sit behind it and the policy decisions that it drives.

The cheaper food paradigm

The assumptions that sit behind this are that: consumption drives growth; that cheaper food is good for growth; that markets are the best way to provide cheaper food; that changing diets is not the job of government, and that food safety nets are not needed—or need only to be minimal.

Policy therefore focuses on driving efficiency and market liberalisation, while not worrying about waste (an inevitable product of the system) or ill-health. Farming focuses on a few commodities, grown intensively and at scale.

Market concentration

Markets are dominated by few, big players, with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Their market position means that they can absorb competitors and acquire innovators, while their own innovation focuses on scale and efficiency. New entrants and disruptors face significant barriers to entry.

Path dependencies

The weight of the investment in the food sector acts to reinforce this system, and it is reinforced by most of the incentives in it—including (although Tim didn’t mention it) the way in which investors assess publicly quoted companies, meaning those listed on stock markets. The near monopolies created by market concentration are able to leverage pricing in ways which means that means that “cheap food” often has high margins, which investors like but which has terrible external costs.

Some of these external costs include environmental impacts, which are not costed, and the whole system generates huge barriers to transformative change, both politically and economically.

The overall cycle looks something like this.

(‘The triple lock in’. Tim Benton/Chatham House, adapted Andrew Curry.)

Although this all looks pretty entrenched, Benton’s view is that it is quite unstable. It looks familiar but it’s already threatened by changing circumstances. The health and environmental costs of this model are already undermining perceptions of the cheaper food paradigm, and on top of that some of the geopolitical conditions that support it—such as relative global stability, open markets, and so on—have started to fragment into a world of onshoring and ‘ally-shoring’. Protectionism and nationalism are undermining the model.

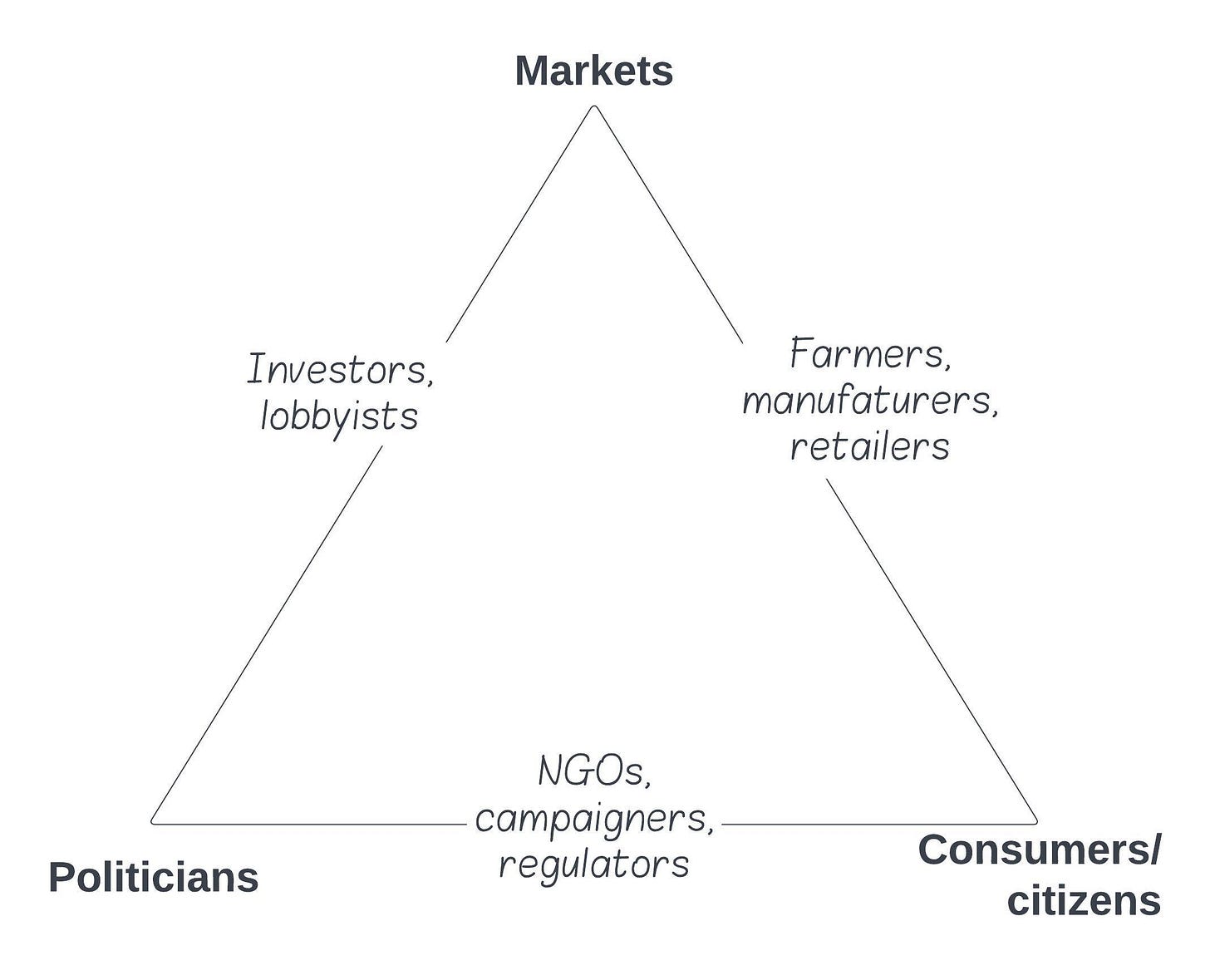

So it’s also worth looking at the story that Benton told about the political environment in which the food system gets negotiated. He had a chart which showed a triangle of markets, politicians, and consumers/citizens. (And whether consumers/citizens see themselves primarily as citizens or consumers does matter here.)

(The political economy of food. Tim Bention/Chatham House, adapted Andrew Curry)

The politics of food plays out between these different actors and the intermediaries between markets, politicians, and citizens/consumers. I’ve added some extra intermediaries to Tim’s diagram here. It’s possible to imagine—but I was trying not to complicate things too much—that there are also interactions between the different intermediaries running across the middle of the triangle as well.

This triangle, he argued, is being destabilised by externalities. Events that were triggered by these externalities would, he thought, change the political dynamics around food at some point. Events might shift values as well. He thought that this might happen quite quickly, as possibly also quite soon.

In short: unlocking the triple lock-in is essential if we are going to get to systemic change in the food system, and that systemic change is necessary if we are going to address the climate and health impacts of food.

But the combination of the costs of the current system, and events triggered by crises in the current system, could well drive this systemic change. As Tim concluded, “The politics will change as the world changes.”

2: Art for art’s sake, and the Romantic moment

History doesn’t repeat itself but it sometimes rhymes. That is roughly the hypothesis that the music writer Ted Gioia is testing in a recent post at his Substack. He has been looking at the rise of Romanticism at the start of the 19th century, and wondering if there are parallels between that time and now.

Of course, this kind of talk is catnip for futurists.

This idea started life as a throwaway remark, “almost a joke”, as he says in the article:

I said that technocracy had grown so oppressive and manipulative it would spur a backlash. And that our rebellion might resemble the Romanticist movement of the early 1800s.

And then he decided to do some research. Summarising a bit, this is the world of 1800, as he describes it.

Rationalist and algorithmic models were dominating every sphere of life at that midpoint in the Industrial Revolution—and people started resisting the forces of progress.

Companies grew more powerful, promising productivity and prosperity. But Blake called them “dark Satanic mills” and Ludditesstarted burning down factories...

Even as science and technology produced amazing results, dysfunctional behaviors sprang up everywhere. The pathbreaking literary works from the late 1700s reveal the dark side of the pervasive techno-optimism.

There’s a bit more here. As the turn of the century approached, composers and writers started attacking these new strands of rationalism. New works “celebrated human feeling and emotional attachments”. That’s 1800, give or take.

His version of what this might look like today:

Imagine a growing sense that algorithmic and mechanistic thinking has become too oppressive. Imagine if people started resisting technology. Imagine a revolt against STEM’s dominance. Imagine people deciding that the good life starts with NOT learning how to code.

So, he tells us, about nine months ago he started to do some serious research on the Romantic movement, and he says he’s been working on this several hours every day, reading the books and the secondary sources, listening to the music and looking at the paintings.

He’s not sure what to do with this material, but anyway he shares some of the research notes he’s been making as he goes (and it’s always good to watch a researcher at work).

I put a lot of energy into note-taking—so this may also be of interest to readers who have asked about my research methods. Consider the notes below as typical of the material I write for my own benefit, but rarely publish.

They’re maybe a bit less random than he claims them to be. They are also oriented around music:

I firmly believe that music is an early indicator of social change. The notes below are offered as evidence in support of that view.

The notes cover the years 1800 to 1804. I’m just going to share some of these here.

1800

Haydn publishes The Creation in 1800—a milestone moment for those (like me) fascinated by artists who grow bolder in their 60s and 70s. But the modernism here goes beyond the music. Haydn leaves church patronage behind, and performs his hot new work for ticket holders at Covent Garden and elsewhere.

Wordsworth announces (the arrival of pop culture) in the new edition of his Lyrical Ballads (1800), inserting a flaming manifesto as preface. He mocks previous writers for their elitism, and insists that the language of the common people is more artistic—from now on poets should focus on “incidents and situations from common life ... in a selection of language really used by men.”

Of course, Wordsworth’s poems don’t sound anything like ordinary speech (nor those of co-author of Lyrical Ballads, Samuel Coleridge). But they are different. They sound like folk ballads. In Germany, Herder has already done something similar, drawing on folk ballads to define an “authentic” culture. Still in 1800:

Beethoven turns thirty, and this is much more than a symbolic coming of age. Over the next three years, Beethoven invents an entirely new emotional vocabulary for Western music... This is also the year of his first symphony and the third piano concerto—works full of anticipatory rebellion. You feel the beast trying to break out of the cage.

And still in 1800, Schelling publishes System of Transcendental Idealism, in which

art heals the divide between objectivity and subjectivity, the inner life and outer world, philosophy and science, etc.

Gioia suggests that Schelling’s concept of the unconscious prefaces the work of Jung a century later:

The unconscious here isn’t something to fear. It is now the source of freedom.

1803

Beethoven, who has moved to the country because of the onset of his deafness, is working on his Eroica Symphony.

Has there ever been a composer operating so far ahead of peers and rivals? Nobody in the world, circa 1803, has even started to assimilate what Beethoven is doing. Who are his leading competitors after Haydn steps aside? Hummel or Weber? Salieri or Cherubini?

1804

The first use of the phrase “art for art’s sake” dates from this year—it quickly spreads all over Europe. This is more than a defense of the creative spirit. It’s also a rebuttal to scientism and its pretensions as the ultimate ruler of human destiny.

Gioia has this odd but interesting theory in his notes that our ways of seeing the world are shaped by whether we see the world as light or dark. In 1801 Novalis died shortly after publishing Hymns to the Night, which starts to create “the noir aesthetic”:

Darkness will never be more fashionable than at this moment in time. The first step, it seems, in countering rationalism, is to remove the light from the Enlightenment. So we will now see an avalanche of poems about sleep, dreams, nightingales, stars and moon, as well as the dark recesses of the inner life.

In the current moment, he suggests, we are similarly moving from an aesthetics of light to an aesthetics of dark:

When rationalistic and algorithmic tyranny grows too extreme, art returns to the darkness of the unconscious life—and perhaps of the womb.

(Caspar David Friedrich, ‘The Abbey in the Oakwood’. 1809-10. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Public Domain)

In 1804, Beethoven turns against Napoleon:

Not long ago, Beethoven and other artists looked to French rationalism as a harbinger of a new age of freedom and individual flourishing. But this entire progress-obsessed ideology is unraveling.

That’s the Romantic bit of the argument, anyway. Gioia finds it interesting, as someone who is best known as a music writer, that this is the first time in history that music takes the lead as an agent of cultural and social change.

If music did that now, he asks, what would it sound like? What’s the 21st century equivalent of Beethoven?

Update: The Beatles

It was the 60th anniversary this week of the Beatles second LP with the beatles, and the music writer Richard Williams wrote a short column noting how radical it was when it came out in 1963. The look, first: more like the French New Wave than the typical pop music promo shot. And then there was the selection of music: again breaking the mould for early 1960s pop releases, the record didn’t include ‘From Me to You’ or ‘She Loves You’, which had been No. 1 hits earlier in the year, or their about to be released single ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’. Yet despite this, or because of it, the record had advance sales of half a million copies.

But Williams, who was 16 when it was released, is more interested in the impact, which was immediate:

Within days of its appearance on 22 November 1963, with the beatles was a presence in just about every home in the land containing one or more teenagers, irrespective of social class. For a pop record, that universality was a first. It also arrived just in time for Christmas parties, at which it became a fixture, whether in stately homes or council houses. In my memory, it represents the moment that sealed their acceptance as something much more than just the latest chart sensation.

j2t#518

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.