10 May 2024. Technology | Eurovision

How technology “enshittification” works in practice // Looking at Eurovision through a loser’s lens. [#569]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: How technology “enshittification” works in practice

Cory Doctorow’s Pluralistic newsletter and articles are must-follow if you’re interested in the political economy of technology, and last year he introduced a new term to the technology lexicon: “enshittification”. This refers, broadly, to the process whereby the technology giants have, over time, systematically locked in users and then degraded the value that they get from those services. (I wrote about his idea here).

He’s come back to this in a recent article in Locus magazinebecause he observes that if all of the tech giants are doing it, then it must be a systemic feature of the sector.

Just a reminder, before we get into this, of what this process involves:

(E)nshittification is a three-stage process: first surpluses are allocated to users until they are locked in. Then they are withdrawn and given to business-customers until they are locked in. Then all the value is harvested for the company’s shareholders, leaving just enough residual value in the service to keep both end-users and business-customers glued to the platform.

He proposes YouTube as a case in point. Here’s his list of the ways in which YouTube has deteriorated as a customer offer over the past year:

Google has:

Dramatically increased the cost of ad-free Youtube subscriptions;

Dramatically increased the number of ads shown to non-subscribers;

Dramatically decreased the amount of money paid to Youtube creators;

Added aggressive anti-adblock;

Then, this week, Google started adding a five-second blanking interval for non-Chrome users who have adblockers installed.

(Image: Rush4Art, CC)

Reading his article, Doctorow is suggesting that the reason this happens is an interplay between two things. The first is what I might call micro-forces within the company—about product managers with targets trying to meet their KPIs (performance indicators), which are also typically linked to career progression and, in the American corporation, end of year bonuses.

The second is about the wider macro corporate objectives: maintaining Google’s market share and vast profit margins. The individual KPIs of the individual product managers are an imperfect management tool that is designed to connect the second to the first, the macro to the micro.

And of course, this is a strategy. As Roger Martin says in a piece I noticed this week,

A company’s strategy is what it does. Its strategy is the set of choices that it has put into action over time.

Doctorow suggests that the first one, typically, starts out as an argument in a meeting. This might be product development, or it might be a marketing meeting or a finance meeting. For example:

At some product planning meeting, one person will propose doing something to materially worsen the service to the company's advantage, and at the expense of end-users or business-customers.

Doctorow is writing about Google because he knows the company quite well, and because it’s an example that everyone knows. But once you know about the “enshittification” framework you start to see it everywhere.

Of course, there are risks in making a product worse. It alienates your workers, for one thing:

People like doing a good job, and they take pride in making good things. Many have sacrificed something that mattered in the service of making the product better. It's bad enough to miss your kid's school play so you can meet a work deadline – but imagine making that sacrifice and then having the excellent work you put in deliberately degraded.

At the project management level, this personal discomfort can sometimes be allied with an argument about the impact on usage or revenues, to at least some effect. The fact that this seems not to be happening any more confirms to me that the digital technology sector is now at the end of its S-curve. (Carlota Perez’ technology model would suggest this as well.) It’s reached the market maturity stage—‘winter’, as the S-curve king Theodore Modus described it—where there’s no new customers and no easy money any more. Hence they are responding to investor pressure by doing whatever they can to milk their customer base.1

This is why this is now a systemic issue across the tech sector. In Facebook, as Jason Koebler pointed out in a recent post at 404 Media, it now takes the form of a “zombie internet” in which AIs and bots compete to attract the attention of human users while steadily diminishing the quality of their user experience.

Doctorow observes that companies are normally restrained through one of three things: fear of competition; fear of regulation; and fear of customer reaction. The first isn’t really working at the moment, because the anti-trust system in the US has been broken for most of the past 30 years and so these companies are vast quasi-monopolies. The second is starting to show some teeth, belatedly, on both sides of the Atlantic. The third: It’s hard to walk away as a customer, but people do instal ad-blockers in significant numbers (33% of users worldwide, in 2023), and they do just use services less as their experience of them degrades.

But the pressure from investors is the noise that companies hear most loudly, which is one of the reasons why capitalism is so toxic at the moment. I tried to do some work on this when thinking about the fight between the short-term and the long-term in a report I co-wrote on “better business”. I wrote about this here about a year ago, and that piece has the detail in it.

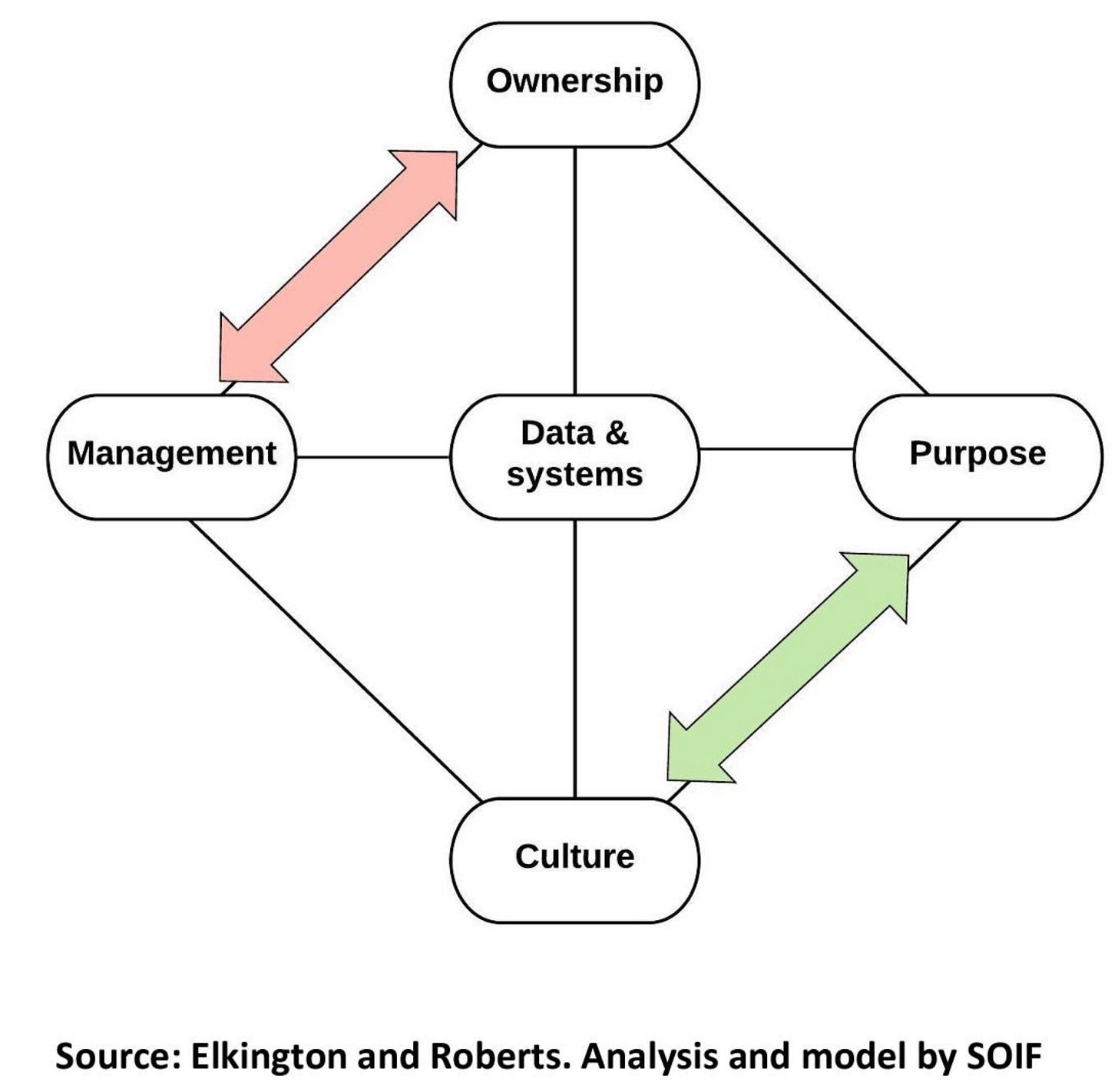

In over-simplified summary through, the fight between short-term and long term ends up being a fight between an ownership-management axis on the one hand, and a purpose-culture axis on the other.

The “enshittification” process works by imposing systems of management control and staff incentives that are designed to weaken sense of purpose and a culture about doing worthwhile work. This is also, always, where the “saying/doing” gap is in organisations: an FMCG/ packaged goods business might talk a good game on sustainability but if the sales teams have KPIs based on the volume of product they shift, the talk won’t mean much.

This is one of the reasons why financially driven short-termist owners (I’m thinking about Boeing here) need to attack cultures that are about technical excellence. In Boeing’s case, if they’d stuck with the culture and purpose the business already had, the shareholders would now be much better off, as it happens. Not all businesses are at war in this way, although the influence of investors—actual or perceived—is generally malign. And that’s one of the other reasons why good, effective, regulation is needed—to reinforce cultures of quality against the attacks of finance.

2: Looking at Eurovision through a loser’s lens

It’s time for the Eurovision Song Contest again, and at the perhaps unlikely location of the European Review of Books, and in front of their paywall, there’s an article by the Lithuanian writer Justina Buskaitė on the experience of Eurovision from the perspective of a small nation with an unimpressive track record. It’s called, ‘We are the winners of Eurovision’. She’s been watching Eurovision, with its endless Lithuanian disappointments, since 2004.

(Outside the Eurovision Song Competition venue, Malmo, 2024. Photo: News Oresund, CC BY 2.0)

In 1994, the Lithuanian entry ‘Lopšinė mylimai’, by Ovidijus Vysniauskas, placed last with nul points, and Lithuania were disqualified from the competition for three years. Things haven’t been as bad as that since then. But there are many ways to lose at Eurovision. Of Lithunia’s entries since 1994,

☞ seven failed to qualify for the Eurovision final;

☞ eight placed at the bottom half of all the entries;

☞ three have placed so low that Lithuania was disqualified from competing in the next year’s contest;

☞ three have made it to the top 10!

☞ zero have been close to the podium.

The language of the song lyrics doesn’t make any difference. Lithuanian has lost with songs in Lithuanian, in Samogitian (a west Lithuanian dialect), in English, in French, in German, in Russian, and in American Sign Language.

We all know what a Eurovision winner sounds like, as she reminds us:

Can you imagine it playing in a shopping mall in Slovenia? What about a gas station in Italy? That is your Eurovision-winning song. It should feel, in a good way, like listening to the radio in a foreign country, a thing you both have and have not heard before, sung with a depth of commitment and a conspicuously clear enunciation of every single word.

But losing is a whole different matter. And even for a small country like Lithuania, losing at the Eurovision Song Contest is quite an expensive hobby.

The competition is the creature of the the European Broadcasting Union, which is described on Wikipedia as “an alliance of the world’s public service broadcasters”. Eurovision was created in 1956 as a vehicle to promote post-war unity in Europe. These days the Eurovision network extends beyond Europe, which is why Australia gets to take part in Eurovision, and Israel, controversially this year.

But back then it was a European initiative. At first there were no conditions on language, until Sweden entered an English-language song in 1965, and the rules were changed to ensure that competitors sang in one of the national languages of the country they represented. The rule was removed for a brief window in the early ‘70s—long enough for Abba to climb through it with ‘Waterloo’ in 1974–then finally removed for good in 1999.2

The EBU charges for participation. In recent years a small country like Lithuania has paid anywhere between €30,000 and €90,000 to enter, while one of the ‘big five’ broadcasters—the UK, Italy, France, Germany and Spain—can pay up to €400,000.

That’s just to get into the competition, and staging costs are on top of that:

it is up to the selected act and the national broadcaster to cover everything that will deliver a winning performance to 160 million people: costumes, stage design and props, lighting. Special effects like pyrotechnics, wind, and fog are rumored to cost around €10.000 to €20.000. Eurovision sells the most expensive wind in the world.

Buskaitė jokes—I think it is a joke—that taking part in Eurovision seems to be a necessary step for any country hoping to join the EU:

First EBU, then Eurovision, then membership in the European Union and/or NATO? That, at least, has been the path that most eastern European countries have taken since the early 1990s. Eurovision would seem to be the most anti-political or even utopian item on that list.

There is a serious point in here. In theory, at least, Eurovision songs are not supposed to be political, even if unmistakable political meanings get smuggled in from time to time. Cultural politics is different: there have been drag bands and same-sex kisses (by Lithuania, in 2004, even though same-sex marriage has even now not been legalised in Lithuania.)

But I need to get back to her thread about losing Eurovision.

The worst and surest formula for losing Eurovision — or maybe the cheapest one? — is to write a song about winning Eurovision. In 2006, Lithuania’s song was ‘We Are the Winners’. It’s dominated by its a chanting chorus “we are the winners of Eurovision / we are, we are / you gotta vote, vote, vote, vote, vote for the winners”. Today we’d call this manifesting.

She describes it at length, and it sounded dismal enough that I thought additional research was required:

It didn’t win, but it did come sixth—Lithuania’s highest ever placing. But maybe it touched the zeitgeist that year, since Iceland tried a similar strategy, less successfully. These are the lyrics of ‘Congratulations’, by Silvia Night:

“Eurovision nation, your dream’s coming true / You’ve been waiting forever for me to save you,” she sang. “Born in Reykjavik in a different league, no damn Eurotrash freak / The vote is in, I’ll fucking win.”

She didn’t win. She didn’t get out of the semi-finals. And no song about Eurovision has won Eurovision.

After the financial crisis, in 2010, the Lithuanian entry had to be subsidised by a commercial company. The head of Lithuania’s public service broadcaster, LRT, said publicly,

Given the current economic situation, God forbid Lithuania wins Eurovision this year.

That year’s entry was ‘Easter European Funk’, by the ska-funk band InCulto. Lithuania had seen a huge wave of outward migration as a result of the crisis—to Norway, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Great Britain. The song—in English—spoke to that sense of being a second class citizen:

Yes sir we are legal we are

Though we are not as legal as you.

No sir we are not equal no

Though we both are from the EU.

The song ended with a flourish that was a visual play on a Lithuanian phrase, nusimaus paskutinius triusikus, which means “to take off one’s last pair of underwear.” It’s about extreme measures or last resorts. In the voting it did very well in those countries with a sizeable Lithuanian diaspora. (If you’re only going to watch one former Lithuanian Eurovision entry from this post, make it this one. It’s much more fun than ‘We are the winners’.)

There’s a lot more here: the EBU’s anti-booing technology, which makes sure that neither the performers, nor the television audiences, can hear the audience in the hall if they boo. She deals with the difficult issue of the relationship between the ‘professional juries’ and the votes from the national public in each country. Only once since 2015 have the juries and the public picked the same winner. Last year the professional juries, who preferred the Swedish entry to the public’s Finland, seemed to be swayed by a notion of what a Eurovision song ought to sound like.

She concludes that Eurovision is “the moral equivalent of war”, a phrase coined in 1906 by the American philosopher William James (the brother of the novelist). She thinks that this sums up Eurovision pretty well:

Eurovision entails the competitive passion, a quasi-militaristic sense of national pride... The contest itself sets international alliances in motion, and activates diasporic fifth columns. And what does victory bring? The winner gets to reclaim not only the title of the winner for the year, but also to host the battleground for the next year’s competition.

Fortunately, losing at the moral equivalent of war makes her feel better. Because losing is about supporting the institution of Eurovision—and that makes her feel like a good European. If you have Lithuania’s history, losing is still winning.

j2t#569

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The constant ‘look over there’ noises about shiny new objects with no obvious revenue streams—the metaverse, AI—are another symptom.

For a period in the 1960s and 1970s the Soviet bloc ran a competing competition, Intervision, and it is a sign of the times that Russia—once a Eurovision participant—is currently trying to revive Intervision. Soft power has no limits.