19 October 2024. Demographics (2) | Ballard

The coming world of protracted population decline. It’s not good. // J.G. Ballard’s dystopian dreams about technology [#609]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The coming world of protracted population decline. (It’s not good).

I wrote here earlier this week on the ageing of the world’s population everywhere, pretty much, outside of sub-Saharan Africa, drawing on Nicholas Eberstadt’s recent article in Foreign Affairs (it can be unpaywalled in exchange for an email address.)

In that first piece, I covered the existing data on the decline in fertility levels and the consequences for ageing societies. Eberstadt says it’s definitely a policy problem, but it may not be a catastrophic one. I’m less sure about it not being catastrophic, but I’ll come back to that later on.

Some of the projections for societies such as South Korea that are at the leading age of falling fertility levels, and by extension, the development of ageing, are stark to the point of being dramatic—indeed, Eberhart uses the phrase “mind-bending”:

Current projections have suggested that South Korea will mark three deaths for every birth by 2050. In some UNPD projections, the median age in South Korea will approach 60… South Korea will have just a fifth as many babies in 2050 as it did in 1961. It will have barely 1.2 working-age people for every senior citizen. Should South Korea’s current fertility trends persist, the country’s population will continue to decline by over three percent per year—crashing by 95 percent over the course of a century.

It’s a useful reminder that exponential trends can head down as well as up. But Eberhart’s point is that South Korea is effectively the “frontier” country for these trends. Where it leads, the rest of us will follow.

(South Korea is the poster child for an ageing world. Busan City 2018. Image: Bryan…/flickr.)

The consequences are not good.

The pervasive graying of the population and protracted population decline will hobble economic growth and cripple social welfare systems in rich countries, threatening their very prospects for continued prosperity. Without sweeping changes in incentive structures, life-cycle earning and consumption patterns, and government policies for taxation and social expenditures, dwindling workforces, reduced savings and investment, unsustainable social outlays, and budget deficits are all in the cards for today’s developed countries.

And not just in developed countries. Until now, the countries that have grayed the soonest have been richer countries with reasonable social safety nets in place. But one of the consequences of falling fertility rates in more places is that poorer countries will also need to adapt, with less economic cushion to do so:

The poor, elderly countries of the future may find themselves under great pressure to build welfare states before they can actually fund them. But income levels are likely to be decidedly lower in 2050 for many Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and North African countries than they were in Western countries at the same stage of population graying.

The problem—as Eberhart positions it—is that 60- and 70-somethings may well be active, even economically active, the same is not true for over-80s. This group is the world’s fastest growing cohort (albeit from a fairly small base) and by 2050 in some countries there will be larger numbers of over-80s than children.

(Source: United Nations via Foreign Affairs.)

But the same changes in family structure that have contributed to this demographic shift, which were discussed in Part 1, also mean that is harder for families to help cope with it:

As familial units grow smaller and more atomized, fewer people get married, and high levels of voluntary childlessness take hold in country after country. As a result, families and their branches become ever less able to bear weight—even as the demands that might be placed on them steadily rise.

Eberhart doesn’t really have a solution to this. He thinks that technology might eventually be able to help, but not soon. Carers might come from non-family members. He’s not a fan of the state doing the work, because he thinks it is an expensive substitute for the family, “and not a very good one”.

However, he is confident, I’d say over-confident, that the same trends that have enabled growing prosperity over the past two or three generations might come to our rescue.

The essence of modern economic development is the continuing augmentation of human potential and a propitious business climate, framed by policies and institutions that help unlock the value in human beings... Improvements in health, education, and science and technology are fuel for the motor generating material advances. Irrespective of demographic aging and shrinking, societies can still benefit from progress across the board in these areas.

Even with this level of optimism, he says that the transition to an ageing world will be disruptive. The social care systems we have are basically designed to benefit from growing populations, which is why they have worked over a century or so in which global population has grown sharply:

In depopulating societies, today’s “pay-as-you-go” social programs for national pension and old-age health care will fail as the working population shrinks and the number of elderly claimants balloons.

He thinks that the societies that succeed will be more open—more open to innovation, more open to migrants. I can see the second point, although this is most likely to make the ageing crisis more acute in countries with less resources as people leave. This is a beggar-your neighbour world. I understand the theory about the first point, but one of the things we also know is that the rate of innovation is slowing down.

Eberhart also seems blind to the likely effects of climate change in this future world, which is also likely to impose much greater costs on states. And climate change will have worse effects on older citizens—extreme heat, notoriously, is hard for the very old and the very young to deal with.

This is Foreign Affairs writing, and inevitably he has a poke at the geopolitics. Most of the young people in this future world will be African, but this will not lead, he says, to “an African century”, since skills and investment levels remain patchy on the continent. (Even though young workers are at a premium in this world?).

India’s population profile means that it will be “a leading power” by 2050. But again, although some of its top level skills are world class,

ordinary Indians receive poor education. A shocking seven out of eight young people in India today lack even basic skills—a consequence of both low enrollment and the generally poor quality of the primary and secondary schools available to those lucky enough to get schooling.

China—ageing far more quickly—has a far more skilled population in comparison.

And although the United States has sub-replacement fertility levels, it has a younger population than many places because of relatively high immigration levels, and will, says Eberhart, prosper, at least relatively, if it continues with its relatively open immigration policies.

The other big question is how countries react to this crisis of ageing.

Nothing guarantees that societies will successfully navigate the turbulence caused by depopulation... To achieve economic and social advances despite depopulation will require substantial reforms in government institutions, the corporate sector, social organizations, and personal norms and behavior.

He doesn’t say this, but in practice we have already seen some of what happens in depopulating societies, since regional depopulation is already associated with the rise of far right political parties, and people who have less optimistic views of the future are also more likely to turn to the right. We don’t know yet whether this effect is a cohort effect or not—older voters in declining areas may also hold more traditional values, whereas the 60-70 year olds in 2050 are Millennials, and may have different values. (Eberhart doesn’t discuss this).

But the economics are stark: most of the world’s GDP is produced in countries that will be depopulating in 2050:

The nightmare scenario would be a zone of important but depopulating economies, accounting for much of the world’s output, frozen into perpetual sclerosis or decline by pessimism, anxiety, and resistance to reform.

2: Ballard’s dystopian dreams about technology

You know how it is. You don’t think about J G Ballard for months, and then two articles come along at once. (Well, strictly speaking one article came along at the same time as I stumbled on the other in a book I happened to be reading.)

The article first, since it is more wide-ranging. It is on the book review site Book Post, and is written by the novelist Deborah Levy:

J. G. Ballard, England’s greatest literary futurist, changed the coordinates of reality in British fiction and took his faithful readers on a wild intellectual ride. He never restored moral order to the proceedings in his fiction because he did not believe we really wanted it.

Ballard was born in China, where his father ran the China Printing and Finishing Company, and spent some of the Second World War in a Japanese internment camp in Shanghai. He wrote about this, eventually, in his book Empire of the Sun, which was filmed by Spielberg. When Levy asked him why it took so long to write the novel, he told her

that it took him “twenty years to forget and twenty years to remember.”

He first set foot in the UK in late 1945, at the age of 15, and there’s a sense that he was never completely at home here. He always saw it with the eye of an outsider.

(Cover designs by David Pelham. Source: Jim Linwood/Flickr. CC BT 2.0)

That’s the argument that Zadie Smith makes in her piece on Ballard’s 1973 novel Crash. It was written as an introduction to a 2014 reissue, and is republished in her 2018 collection Feel Free, which I happened to be reading.

She met Ballard in the early 2000s, a few years before his death, when he was in his 70s and she was a Young British Writer. It was on a pleasure boat on the Thames that was full of writers, for reasons that she forgets. They talked at cross-purposes:

Ballard was a man born on the inside, to the colonial class, that is, to the very marrow of British life; but he broke out of that restrictive mould and went on to establish— uniquely among his literary generation—an autonomous hinterland, not attached to the mainland in any obvious way. I, meanwhile, born on the outside of it all, was hell-bent on breaking in.

Almost all of his literary career was spent making the modern world in general, and Britain in particular, seem strange. Smith’s discomfort with Ballard’s work, and in particular with Crash, was partly that he took the urban landscapes of west London where she grew up and turned them into monstrosities. This is an extract that she quotes from Crash:

'The entire zone which defined the landscape of my life was now bounded by a continuous artificial horizon, formed by the raised parapets and embankments of the motorways and their access roads and interchanges. These encircled the vehicles below like the walls of a crater several miles in diameter.’

This is, of course, the landscape of Smith’s life as well, reinterpreted to her:

Ballard was in the business of taking what seems 'natural’—what seems normal, familiar and rational—and revealing its psychopathology.

In her piece, which focuses more on Ballard’s later novels, Levy suggests that much of Ballard’s fiction—often patronised early in his career as ‘science fiction’ by a British literary establishment that preferred to be dismissive rather than discomfited—was about making sense of those early years in wartime Shanghai:

I have always thought that his books, with the exception of Crash, which seems to me an abstract attempt to grieve for his dead wife, were already written in that one room he shared with his parents between 1943 and 1945... Home was the imagination. I too was attracted to the paintings of de Chirico and Delvaux, with their dreamplaces—empty, melancholy cities, abandoned temples, broken statues, shadows, exaggerated perspectives. Ballard was going to make worlds we had not seen before in British fiction.

The world of Crash certainly went beyond the literary world. It influenced many of the electronic artists who emerged in Britain in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It inspired Daniel Miller to write ‘Warm Leatherette’, later covered by Grace Jones. As Simon Reynolds suggested, it’s hard to imagine that John Foxx would have recorded ‘Underpass’ before Crash was published.

The novel was regarded as almost pornographic when it was published in 1973, and Ballard didn’t shy away from this. He called it the first “pornographic novel about technology”. But it also prefigures some important ideas about technology. It captures the convergence of celebrity and car crash, depicting the death of a fictional Elizabeth Taylor, in a line that runs from the non-fictional James Dean and Grace Kelly to Princess Diana.

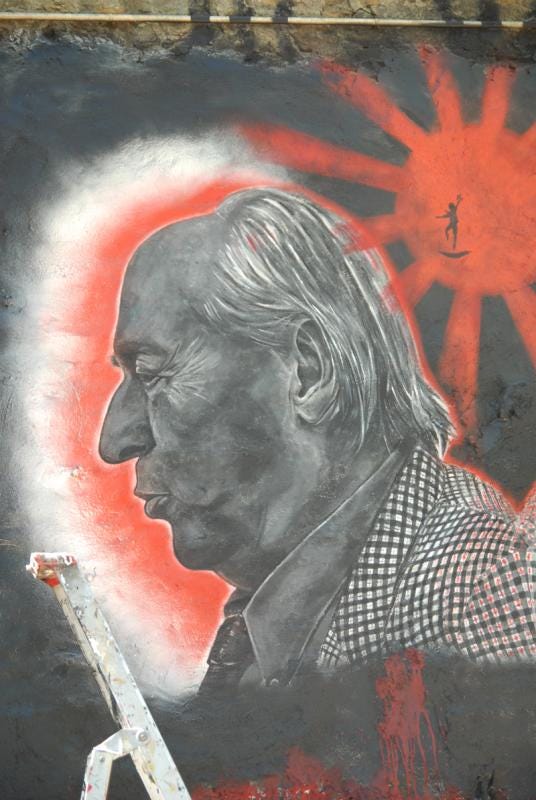

(Portrait of JG Ballard by Thierry Ehrmann/flickr. CC BT 2.0)

Crash also seems like an early echo of Paul Virilio’s famous later line about how all technologies carry within them their inversion:

When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution…Every technology carries its own negativity, which is invented at the same time as technical progress.

The most interesting sections of Smith’s introduction to Crash are about Ballard’s relationship to technology, and therefore our relationship with it:

The real shock of Crash is not that people have sex in or near cars, but that technology has entered into even our most intimate human relations. Not man-as-technology-forming but technology-as-man-forming... The iciness of Ballard's style is party a consequence of inverting the power balance berveen people and technology, which in turn deprives his characters of things like interiority and individual agency. They seem mass-produced, just like the things they make and buy.

Smith suggests that in Ballard’s work there is always “a sweet spot where dystopia and utopia converge.” Because, as she concludes, we have got the technology that we dreamed of:

The dreams have arrived, all of them: instantaneous, global communication, virtual immersion, bio-technology. These were the dreams. And calm and curious, pointing out every new convergence, Ballard reminds us that dreams are often perverse.

j2t#609

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.