16 October 2024. Demographics | Fathers

Women don’t want to have children anymore. // ‘What does it mean, to die with nothing?’

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

It seems that Just Two Things #607, which was published on Saturday morning, may not have been emailed to all readers. If you missed it, you can read it here.

1: Women don’t want to have children any more

Nicholas Eberstadt has an article in Foreign Affairs on what he calls “The age of depopulation”. (It seems to be outside of their paywall). It would be more accurate, of course, to call it “the coming age of depopulation—we’re not quite there yet. But when global population does decline, it will be the first time since the Black Death, 700 years ago, that global population has fallen. Unlike the Black Death, however, this decline in population numbers will be driven entirely by social choices:

With birthrates plummeting, more and more societies are heading into an era of pervasive and indefinite depopulation, one that will eventually encompass the whole planet. What lies ahead is a world made up of shrinking and aging societies. Net mortality—when a society experiences more deaths than births—will likewise become the new norm.

This change is being driven by a deep-rooted collapse in fertility in most parts of the world. It’s impossible to overstate how big a change this is in human experience: we have no experience as a species of long-term depopulation:

A revolutionary force drives the impending depopulation: a worldwide reduction in the desire for children.

In some countries—mostly those who are “at war with modernity” and have much rhetoric about the importance of family life—governments have tried to reverse this decline. They have had absolutely no success. Eberhart argues that “future government policy... will not stave off depopulation.” We will end up, he suggests. With fewer workers and more demand for carers. But, he says, this is not necessarily a catastrophe: instead, it presents a difficult set of issues. But policymakers haven’t started thinking about the implications yet.

(Women on a bench. Free photo via Pexels.com)

It’s a long, long, article, so I’m just going to pull out some of the trends here and then come back to the implications later this week.

The numbers first:

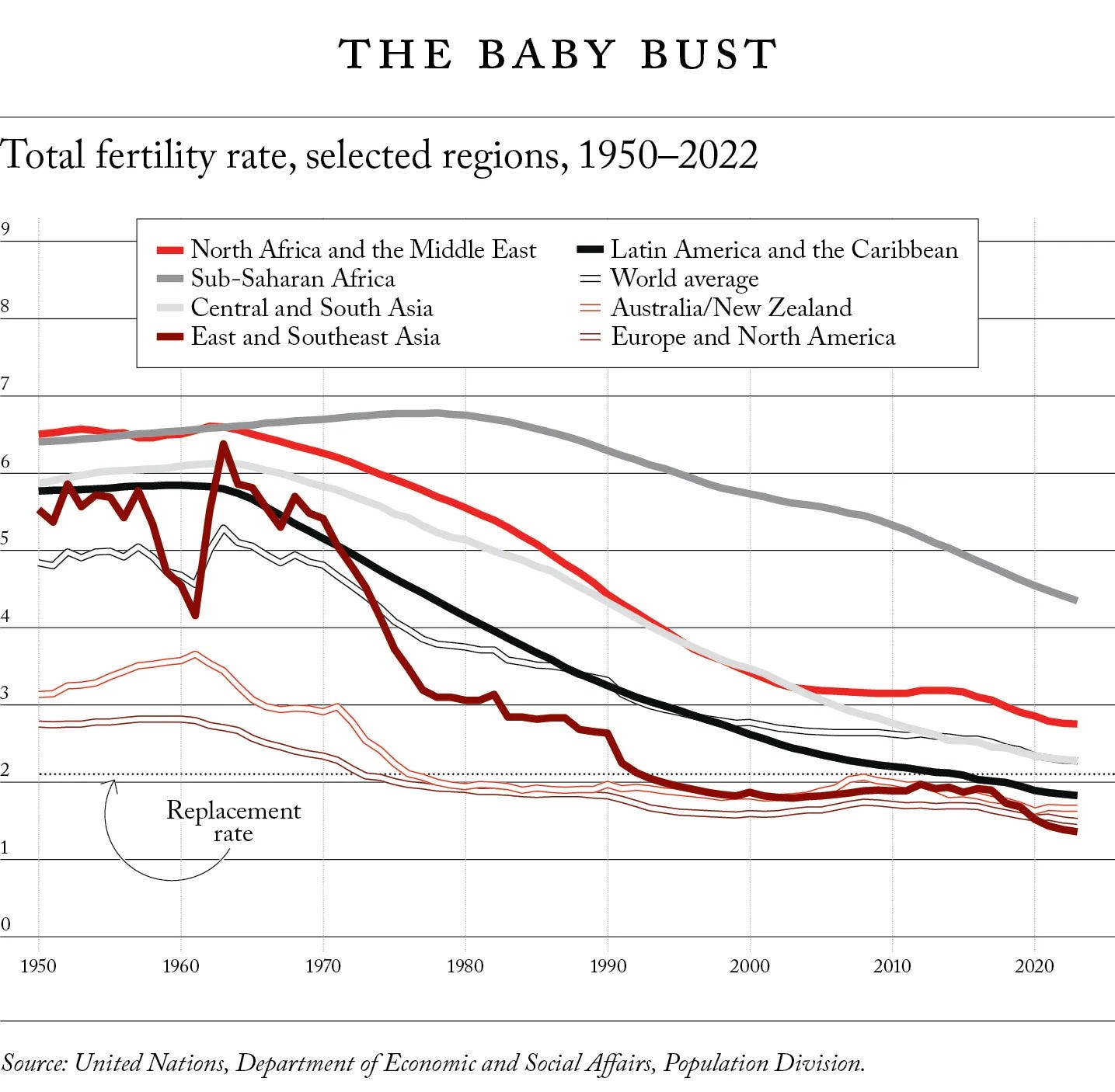

For over two generations, the world’s average childbearing levels have headed relentlessly downward, as one country after another joined in the decline. According to the UN Population Division, the total fertility rate for the planet was only half as high in 2015 as it was in 1965. By the UNPD’s reckoning, every country saw birthrates drop over that period.

By 2019, two-thirds of countries worldwide had fertility levels below the replacement rate (of 2.1 births per woman). Europe, obviously, has had low fertility rates for a while now. But in East Asia, every major country is depopulating:

By 2023, fertility levels were 40 percent below replacement in Japan, over 50 percent below replacement in China, almost 60 percent below replacement in Taiwan, and an astonishing 65 percent below replacement in South Korea.

In south-east Asia, the region as a whole is reckoned to have fallen below replacement levels in 2018; in south Asia, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka are all below, with Bangladesh about to join them. In India, in particular, the fall in urban fertility levels has been dramatic: in 2021, in Kolkatta, fertility levels fell to one birth per woman.1

There’s a similar story across Latin America and the Caribbean, where fertility levels in many countries are just a little above one; again, fertility levels in some cities are at or below one birth per woman.

And the same is true across North Africa and the Middle East.

Iran has been a sub-replacement society for about a quarter century. Tunisia has also dipped below replacement. In sub-replacement Turkey, Istanbul’s 2023 birthrate was just 1.2 babies per woman—lower than Berlin’s.

The only places where this story doesn’t hold up is in sub-Saharan Africa, where fertility rates are around 4.3 births per woman. But they are dropping quite fast.

(Source: United Nations via Foreign Affairs)

The reasons for this are still not clear. It used to be assumed that fertility levels fell as a result of material progress. But none of the traditional markers seem to hold. Countries with low income levels, high poverty levels, low education levels, and low rates of urbanisation are below replacement levels (Nepal and Myanmar, for example).

There’s a mass of sociological research on this, but the explanation seems like it might be simpler:

[I]n 1994, the economist Lant Pritchett discovered the most powerful national fertility predictor ever detected. That decisive factor turned out to be simple: what women want... Pritchett determined that there is an almost one-to-one correspondence around the world between national fertility levels and the number of babies women say they want to have.

Why now? Eberhart offers some threads. There are changes in family formation—with people getting married later, or not at all, or choosing to live alone. These seem to be the case across different cultures and different value systems. The spread of global media may also be a factor. Conversely, religious belief is generally in decline. Eberhart mentions the growth of Inglehart’s ‘post-materialist’ values, associated with the Millennials and GenZ, without mentioning Inglehart:

[P]eople increasingly prize autonomy, self-actualization, and convenience. And children, for their many joys, are quintessentially inconvenient.

One casualty in all of this is the idea that humans are somehow hard-wired to replace themselves. Instead, with a nod to Rene Girard (again without mentioning him) Eberhard says this might be a win for mimetic theory:

[I]mitation can drive decisions, stressing the role of volition and social learning in human arrangements. Many women (and men) may be less keen to have children because so many others are having fewer children.

We don’t quite know yet when the global population will turn. This is a complex system. It really depends on how quickly fertility levels fall in sub-Saharan Africa, so it could be any time between the 2050s and the 2080s. But some projections suggest that by 2050 deaths will exceed births in two-thirds of the world’s countries.

Before that, we’ll see workforces shrink as a result of sub-replacement fertility levels.

By 2050, two-thirds of people around the world could see working-age populations (people between the ages of 20 and 64) diminish in their countries—a trend that stands to constrain economic potential in those countries in the absence of innovative adjustments and countermeasures.

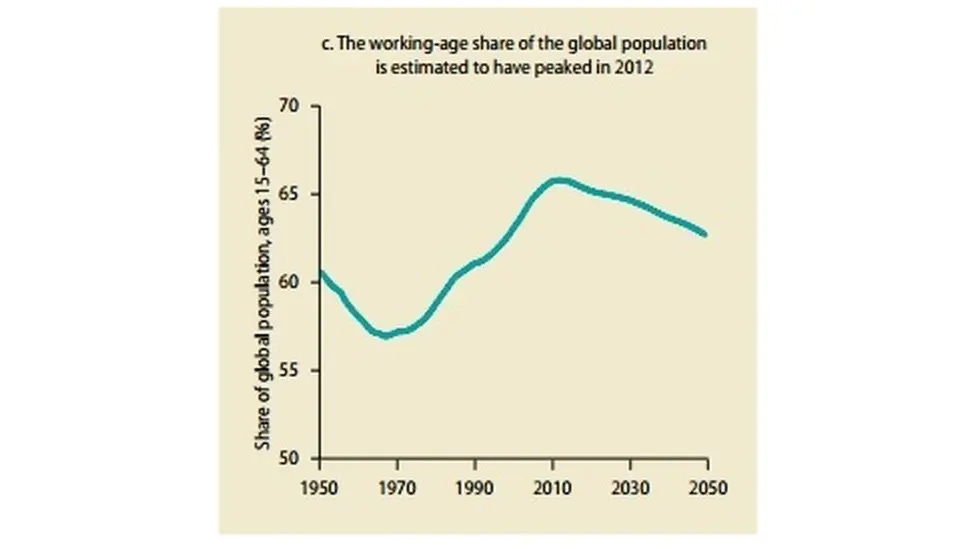

I’m a bit puzzled by this data point, because I had thought that the peak in working age population globally had happened already. Duncan Weldon, then the economics correspondent of BBC Newsnight wrote a piece based on a World Bank report in 2015:

The share of the global population of working age (defined as 15 to 64) is forecast to fall. The working-age share rose strongly for the 40 years to 2012 and the fact it is now falling (a fall driven by both rising longevity and the past impact of a falling birth rate) could have a major impact on the shape of the global economy.

(Source: Global Monitoring Report, via BBC)

No matter, perhaps. The point is that we are headed for ageing populations almost everywhere. Perhaps we are already there: the average age has passed 40 in increasing numbers of countries. And we haven’t been here before as a species. We are used to younger societies. I’ll come back to that part of Nicholas Eberhart’s article in Part II.

2: FATHERS

I’d expected to see more people mentioning Jude Doyle’s extraordinary piece on the death of his father in my feeds. It is called ‘Sixteen Failed Attempts To Write A Eulogy For My Father’. Doyle is an American writer and journalist. It is clear early on that his father was not a nice man:

My father died in a hotel room, having been evicted from every apartment he ever had, and fired from every job he ever had, and having alienated every single person he might stay with.

One of the reasons for this is that he seems to have blamed everyone else for his problems rather than him:

My mother was the last person to speak to him, because he actually never stopped calling her up to scream at her... She tells me that in their last conversation, he told her that everything was her fault...

I said, ‘we haven’t been married for thirty-five years,’ my mother told me, ‘there’s no way any of this could be my fault.’ And he said, ‘oh, yes it is,’ and he called me a bunch of names and hung up.

The coke habit probably didn’t help. His mother called Doyle one week, a few months after he had stopped talking to his father, and told him to go and stay with a friend whose address his father didn’t know, because he was threatening to go round and kill Doyle and then kill himself. Much later, when he asked his mother about this, she didn’t remember it:

When I asked her how she could forget, she said, because he threatened to do that every weekend, honey. That was just the only weekend I was out of town.

Around Attempt #11 (they count down from #16), he’s self-deprecating: “another essay about hating my father”.

But that’s the problem: I did not hate my Dad. I adored him; I worshiped him. When I was a child, I loved him more than anyone on the planet. He loved me that way, too, and he told me so, many times.

You are my reason, the best thing I ever did. You are all the good in me. They took all the good out of me and made it into you...

He would hold my hands and look into my eyes and say these things, over and over, because I was his favorite. I know that, too, because he said all of this in front of my brother, who was also in the room.

But his brother didn’t get the same treatment from his father:

My brother got called fat and a faggot, and sometimes he got furniture thrown at him, for emphasis, because boys have to grow up tough. That was my Dad. He couldn’t even love somebody without using it to hurt somebody else.

At the funeral, his brother gave a eulogy that was respectful, and talked about the kinds of things you can still find to say about a father no matter what: about him playing them Sympathy for the Devil and following the Cleveland Browns, “just good enough to break your heart”.

The drug habit meant that he spent all his money. As Doyle says, “What does it mean, to die with nothing?” His father had had nice things—large screen TVs, a convertible car, leather jackets, “crates and crates” of records, a stereo system, but the money wan’t steady enough and never went far enough. When he finally goes to collect his father’s things from the motel where he lived and died, the manager says to him:

We didn’t know he had any family, the manager said. Nobody came to see him.

Yes, I said. He had some problems.

I mean, you never came to see him.

Yes, I said. But we’re here now.

Well, you see, said the manager of the Motel 6, he left me quite a nice little bill.

As Doyle gets further into the story, the whole thing gets more and more claustrophobic. His father was emotionally needy, over-protective, and censorious. There is constant emotional blackmail. It is a terrible combination. I’m not going to try to capture this; I wouldn’t do the writing justice by picking an extract. But it is chilling.

There was a five-day gap between the last time anyone saw his father and when his body is found in Room 211 at Motel 6. Doyle translates the medical language in the autopsy report as “He drank until his heart stopped working.”

How does a human being die, completely alone, with nothing? It’s an argument here, a thrown chair there; it was the first beer he ever drank, it was the first time he hit my mother; it’s a homophobic slur, it’s a missed visitation day, it’s a shitty remark at an intervention — it’s all just a series of mistakes, large ones and small ones, but mistakes, and then one day he passed the point of no return.

You’ll get the idea that it is a long piece, and he says as much in a note at the end, and in an age when there is a lot of performative writing about difficult family relationships, it feels like an honest attempt to deal with a lifetime of hope dashed by disappointment.

As he writes in Attempt #2,

Maybe every failed relationship has its perfect moment — that one day you can look back on, and say, that’s what it would have been like, if it was good.

The article comes with a pair of Spotify playlists. The first is called ‘Like Father’, and is subtitled, “Songs that my father thought were about him”.

It catches almost exactly the self-delusional sense of the man that Doyle has conveyed in the article.

The second is called ‘Like Son’, and is sub-titled, “Songs that I think are about my father”.

It is less mainstream, but it is the perfect soundtrack for the article.

Update: Dams and salmon

I wrote here last year about the plans to remove the four dams from the Klamath River, which runs along the Oregon-California border, after a long and often frustrating campaign by native American peoples. At the time, ecologists expected the river system to start regenerating quite quickly after the dams had gone.

So I was interested to see how quickly in a piece last week in Energy Collective:

On Oct. 3, researchers saw something nobody had seen for a century. Chinook salmon were swimming freely along the Klamath River in California and Oregon. The arrival of the salmon signaled that the last and largest dam standing of the four hydroelectric dams on the river, the Iron Gate dam, was no more. The dam officially came down on Oct. 2.

The four dams were removed in just eighteen months. All the same, there’s still a lot of ecological work to be done around the river:

Habitat restoration will follow, led by Virginia-based Resource Environmental Solutions, which bills itself as “the nation’s largest ecological restoration company.” The radio account said, “The revegetation of the Klamath River has been called the largest river restoration project in American history. Collecting, propagating, and growing enough seeds and plants to populate the reservoir footprints — approximately 2,200 acres in all — is a staggering task.

Read more: The science of dam removal ( 9 April 2024)

j2t#608

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

This is probably what happens when you combine increasing women’s educational attainment with shocking levels of misogyny and male privilege.