Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Good inflation

Suddenly we’re seeing a lot of noise about inflation, especially from the financial sector. So it’s worth pointing out that inflation can be a good thing.

On this point, there’s a good piece by the economic historian Harold James at Project Syndicate that talks about the role of inflation in sending useful signals to buyers and sellers.

Some examples:

The current surge in the price of computer chips reflects a shortage of supply, which in turn is curtailing production of automobiles, refrigerators, and other products that rely on these components. ... it is giving chip producers a clear signal to ramp up production and increase supply.

Or again, the increasing demand for freight transport, which is pushing up fuel prices, and possibly wages:

What higher gasoline prices will do is signal to consumers that it pays to reduce one’s fuel consumption and dependence on fossil fuels. That message aligns nicely with a wider recognition that the economy urgently needs to shift away from carbon-intensive energy sources. Again, we should allow prices to perform their proper function of guiding consumers’ behavior and future consumption plans.

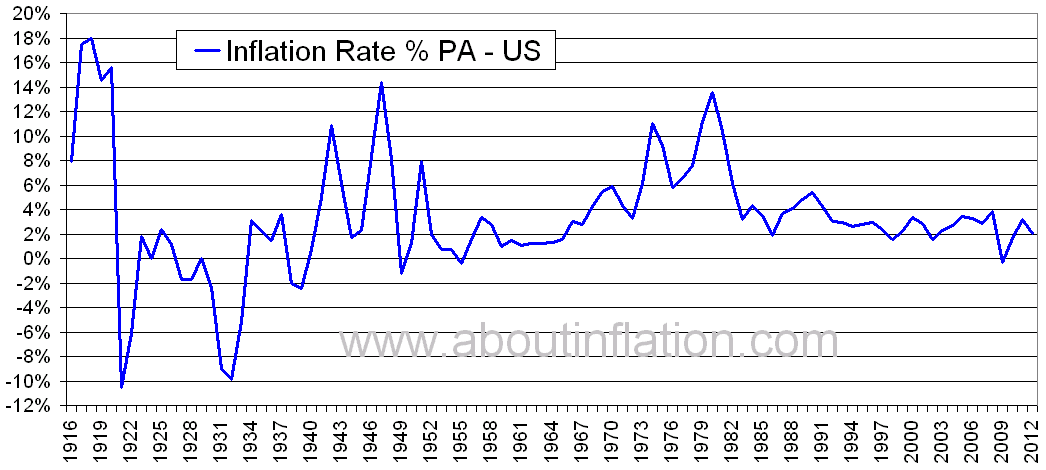

Of course, the spectre that’s always waved around at this point is the rapid inflation of the 1970s, caused by the series of oil shocks. Inflation of that order isn’t a good thing, but even then you can live with it. But the accelerating inflation that causes policy fright is usually associated with periods of accelerating globalisation, or wars.

(A hundred years of American inflation)

James makes a wider point here, which is the policy expectation that inflation should be kept low (2%-2.5%, say) is a leftover from a previous world, the NICE (“non-inflationary continuing expansion”) world described by the former Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, in the pre-financial crisis days.

But we’re no longer in that world. Instead, the world we’re in is one that involves dealing with climate change and other issues which also living with the wake of the global pandemic. This requires dramatic changes in behaviour:

When radical, society-wide shifts in consumption patterns are both expected and desired, it is no longer appropriate to base policy responses on one simple price index. We need to disaggregate prices in a way that aligns with our shared principles and priorities. For example, we should consider excluding the prices of anti-social or otherwise undesirable goods, such as fossil fuels and tobacco products, from the calculation. And we should think of other metrics to help guide us in measuring how efficiently societies and countries are responding to today’s defining challenges.

There’s more to be said here about the political economy of inflation, and I plan to come back to this later in the week.

#2: Unhealthy food

The Financial Times had a story about a leaked internal Nestle presentation which said that less than 40% of the company’s food and drink portfolio, by revenues, met health standards.

Health standards were defined as exceeding 3.5 on the Australian 5-star system. The Australian health star system is regarded as an international reference point.

(I’ve linked to a version of the story republished in the Irish Times because it has a slightly more forgiving firewall).

Overall, the food and drink businesses represent about half of Nestle’s overall £72 billion turnover. So we’re not talking about anything trivial.

By product, around 70% of Nestlé’s food products failed to meet that threshold, 96% of beverages (not including pure coffee), and 99% its confectionery and ice cream portfolio.

Water and dairy products scored a lot better.

And some of the individual products referenced in the article have shocking sodium and sugar levels.

Or, as the presentation puts it, “our portfolio still underperforms against external definitions of health in a landscape where regulatory pressure and consumer demands are skyrocketing.”

This reminded me of one of the six themes in our recent urban food futures report (pdf). The work focussed on food choices in lower income areas, so isn’t completely comparable, but we had a theme called ‘Health in the chain’, which we summarised like this:

As awareness of the lifetime costs of unhealthy diets rises, will regulators and businesses work together to increase access to healthier options in lower income areas? Or will corporate lobbying protect food deserts from regulation?

We analysed this through a set of causal loops, which are also included as an appendix to the report.

(The causal loops for the “Health in the Chain” domain. The top loop increases the availability of healthy foods. The bottom loop reduces it. Source: Urban Food Futures, SOIF/Shift, published by Impact on Urban Health, 2021: p. 65)

I was a journalist for a while, a long time ago, and it’s always interesting when an internal document is leaked to the press. Although the article comes with the usual corporate platitudes, people usually leak things because they’re dissatisfied with how things are going inside an organisation—that they’re not taking something seriously enough, for example.

That might be the case here.

Looking at the article through the lens of the causal loops diagram, it seems to capture both the positive and negative loops. On the one hand, Nestle is, apparently, working to update its internal nutritional standards.

On the other, it’s also thinking of moving some of its categories outside of the standards—for example some of its confectionery products.

At the same time the Chief Executive is not persuaded that “processed” foods are unhealthy per se.

The fact is that it’s difficult to improve the health profile of processed foods, as the distinguished nutritional scientist Marion Nestle (no relation) told the paper:

“Food companies’ job is to generate money for stockholders, and to generate it as quickly and in as large an amount as possible. They are going to sell products that reach a mass audience and are bought by as many people as possible, that people want to buy, and that’s junk food,” she said.

“Nestlé (has) ... a real problem . . . Scientists have been working for years to try to figure out how to reduce the salt and sugar content without changing the flavour profile and guess what, it’s hard to do.”

It’s hard, but it’s not impossible. The companies that don’t apply themselves to the task are likely to face more regulatory scrutiny, may be marked as higher -risk investments, and will end up attracting lower quality recruits.

Update: Peter Curry wrote a Just One Thing last week about Kate Crawford’s work on unravelling an AI. Crawford was interviewed in The Guardian over the weekend on her new book, which builds on the long article Peter discussed.

j2t#113

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.