Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

I have been away for a few days and my son, Peter Curry, has kindly stepped in with some contributions to Just Two Things this week.

Peter Curry writes: This is maybe the closest that AI researchers will ever come to writing a Norse saga, so grab your drinking horn and cuddle up to the hearth.

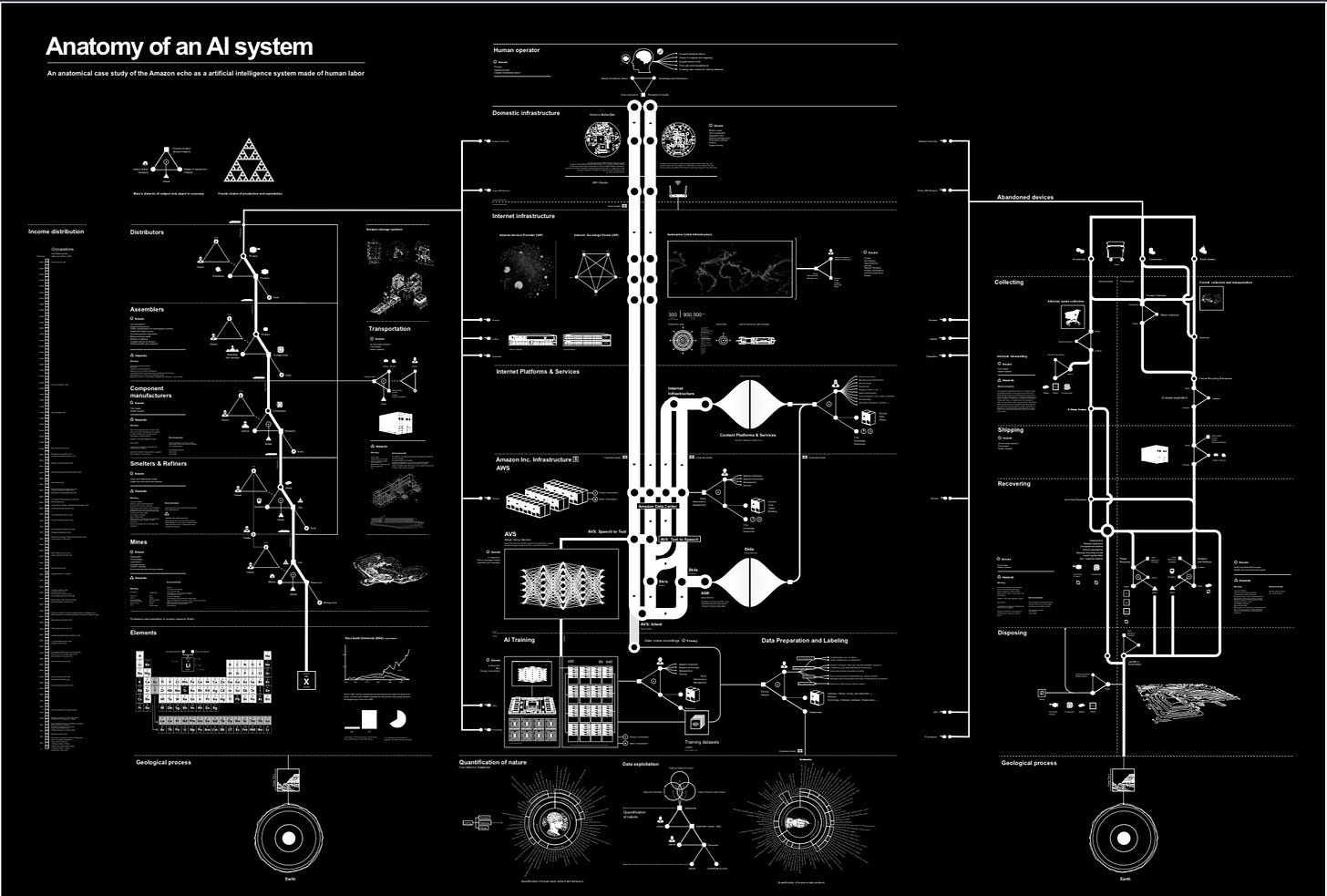

Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler cover every single thing that comprises an Amazon Alexa, from the raw materials, to the research, to the marketing, to the living conditions of the miners, to the deep geological time that we emerged from and will all one day fade back into.

“Put simply: each small moment of convenience – be it answering a question, turning on a light, or playing a song – requires a vast planetary network, fuelled by the extraction of non-renewable materials, labor, and data.”

Crawford and Joler relentlessly document the frangible future of AI, which depends on an endless string of non-renewable resources and exploited labour.

Source: Crawford and Joler

They also produce a map, shown here, documenting the Anatomy of an AI. It’s worth downloading a PDF of the map and having a play, because it is information dense.

“If you read our map from left to right, the story begins and ends with the Earth, and the geological processes of deep time. But read from top to bottom, we see the story as it begins and ends with a human. The top is the human agent, querying the Echo, and supplying Amazon with the valuable training data of verbal questions and responses that they can use to further refine their voice-enabled AI systems.

At the bottom of the map is another kind of human resource: the history of human knowledge and capacity, which is also used to train and optimise artificial intelligence systems.”

Let’s visit the bottom of the map for a moment. The circle in the image below outlines the source data of AI. If you follow this newsletter closely, you’ll be familiar with some of the problems of AI, but as you go around the circle, the complexity of turning so much data into any sort of cohesive system is made manifest.

There are multiple problems with sorting and refining any of those data points into uniform data tranches that are easier for machines to work with. (Here, here, and here, for more on this).

Source: Crawford and Joler

I’m not going to be able to represent even a fragment of the depth and detail that has gone into the entirety of this piece, but there are two more things that are worth reviewing.

The first is the sheer complexity of the supply chains that create these simple tools. Mines, smelting, component manufacture, transportation, assembly, waste. All of these are inordinately complicated in their own right, and a focus on physical supply chains misses the organisational structures that shape AWS and the internet, or decisions about how AI is trained, which would demand essays in their own right.

“One illustration of the difficulty of investigating and tracking the contemporary production chain process is that it took Intel more than four years to understand its supply line well enough to ensure that no tantalum from the Congo was in its microprocessor products.”

It took Intel more than four years to understand its own supply chain. If you’re Intel, it is nigh on impossible to track the companies that you’re being supplied by, because they in turn have their own supply chains, which have their own supply chains. It is a nightmare for the company itself, let alone any researcher or journalist. That there is a new academic field of supply chains, as mentioned in this newsletter a few weeks ago, is a positive step, but also a monumental task.

The second is the ‘Mechanical Turk’. One of Crawford and Joler’s main arguments centres on the idea that AI will look big and scary and monolithic from the outside, but will actually require a significant amount of human intervention on the inside. The Mechanical Turk is Amazon’s admission of defeat on the ability of neural networks and machine learning algorithms to fully train themselves. Instead, they pay online workers scarily low wages to help train the machines.

The original story of the Mechanical Turk is a more comical affair. Invented by Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1770, the Turk was the first ever chess “computer.” It was also a big fat lie. It was just a big machine that let a person hide inside and play chess. Sometimes it is true that the world is overfilled with complexity and that understanding is impossible. Sometimes you just need to pull back the curtain:

#2: Dumping plastics

I realise that Just Two Things is a little obsessed with plastics, but they are everywhere, and so far attempts to manage plastic waste have not been effective.

So this is a nod to the Greenpeace ‘ad’ (1 minute 50) that came out a couple of weeks ago to highlight the amount of plastic waste that the UK generates—and the fact that we’re dumping some of it illegally. The short film is the work of Park Village Studios.

Here’s some of Greenpeace’s notes on why they made the video:

What you see in the film is the amount of plastic we dump on other countries every single day. That’s on average, 1.8 million kilograms a day – or 688,000 tonnes a year of our plastic waste that is fuelling health and wildlife emergencies around the world. Plastic kills hundreds of thousands of marine birds, sea mammals and turtles every year – but it’s not just harming wildlife and our oceans, it’s harming people too. Plastic being sent overseas is being dumped or burned in the open air, with local communities in Turkey and Malaysia reporting serious health problems, like respiratory issues, nosebleeds and headaches.

It’s also illegal to send plastic overseas unless you know that it is going to be recycled, but the UK is sending plastic to countries where it’s not being recycled, as—for example—in the case of Turkey.

The lines in the film from the Johnson and Gove characters are taken from speeches. They did say all of this.

Update: I speculated about the origin of the idea that “data is the new oil” in Just Two Things last week. In his Observer/Guardian column on technology yesterday, John Naughton attributes the phrase to Clive Humby, whose company built the Tesco supermarket loyalty card in the 1990s.

j2t#108

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.