8 February 2025. Risks | Food

The Doomsday Clock moves closer to midnight. // Improving resilience to food system shocks [#629]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

It’s been hard to write here recently. There’s so much noise out there that it’s hard work to discern the signal, and my own work schedule in January has been overloaded, reducing my own ability to process the data. But in getting stuck on that I forgot one of the rules of writing: that when you get stuck on something that’s complex, you should turn to something simpler.

There is some theory to this, although I’m not sure what the neuroscience says. But it’s to the effect that by going away from something, by not staring at it directly, you have your brain do some processing in the background.

Anyway, it has worked, and I’ll come back here soon to the billionaire cabal that is trying to dismantle the American state. For the moment, here are a couple of more straightforward pieces.

1: The Doomsday Clock moves closer to midnight

It’s worth noting that The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has moved the Doomsday Clock a symbolic second closer to midnight, and it now stands at 89 seconds from 12. Symbolic, because it’s now closer to midnight than it ever has been in its 78-year history.

(Source: © The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists)

The annual decision to shift the clock time, published this year on 28th January, always comes with an explanation.

In 2024, humanity edged ever closer to catastrophe. Trends that have deeply concerned the Science and Security Board continued, and despite unmistakable signs of danger, national leaders and their societies have failed to do what is needed to change course.

There’s more, of course. Yes, it’s only a single second, but:

Because the world is already perilously close to the precipice, a move of even a single second should be taken as an indication of extreme danger and an unmistakable warning that every second of delay in reversing course increases the probability of global disaster.

The roll-call of potential disasters is familiar but still alarming. Russia’s war in the Ukraine could spiral out of control through mistake or miscalculation. Israel’s war on Gaza could equally tilt into a regional conflict, even if there have been steps towards a ceasefire since the Bulletin statement was drafted. Meanwhile,

[t]he nuclear arms control process is collapsing, and high-level contacts among nuclear powers are totally inadequate given the danger at hand.

Then there’s climate change. The statement is terse on this but covers a lot of dismal ground:

The global greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change continued to rise. Extreme weather and other climate change-influenced events—floods, tropical cyclones, heat waves, drought, and wildfires—affected every continent. The long-term prognosis for the world’s attempts to deal with climate change remains poor, as most governments fail to enact the financing and policy initiatives necessary to halt global warming.

And as they note, despite all of this, the evidence from election campaigns in the United States and elsewhere, it remains a low political priority.

(Avian flu, as if we haven’t got enough to worry about. Source: IAEA Imagebank/ flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

As an organisation, The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists follows other risks as well, notably biological risks. Avian flu gets a namecheck here, for example, and its spread to farm animal, and to some humans. As with nuclear weapons, oversight of biological risks is not fit for purpose:

Supposedly high-containment biological laboratories continue to be built throughout the world, but oversight regimes for them are not keeping pace, increasing the possibility that pathogens with pandemic potential may escape.

All of this could be exacerbated by large language models and artificial intelligence. For example:

Rapid advances in artificial intelligence have increased the risk that terrorists or countries may attain the capability of designing biological weapons for which countermeasures do not exist.

Or again:

Systems that incorporate artificial intelligence in military targeting have been used in Ukraine and the Middle East, and several countries are moving to integrate artificial intelligence into their militaries. Such efforts raise questions about the extent to which machines will be allowed to make military decisions—even decisions that could kill on a vast scale.

There’s competition in space as well, which seems to extend to military competition.

And all of this plays out against a background of misinformation or disinformation that fuels conspiracy theories, itself amplified by forms of artificial intelligence. This is also something that has been weaponised by states:

[N]ations are engaging in cross-border efforts to use disinformation and other forms of propaganda to subvert elections, while some technology, media, and political leaders aid the spread of lies and conspiracy theories. This corruption of the information ecosystem undermines the public discourse and honest debate upon which democracy depends.

Sitting behind the statement is a set of concise briefing statements: on nuclear risk; on climate change; on biological threats; and on disruptive technologies.

None of them make for cheerful reading.

If I have a disagreement with the argument in the statement, it’s with this:

The battered information landscape is also producing leaders who discount science and endeavor to suppress free speech and human rights, compromising the fact-based public discussions that are required to combat the enormous threats facing the world.

I think it’s the other way around. The leaders who suppress free speech are also producing “the battered information landscape” because it is to their political advantage. Those leaders are—pretty much without exception—opposed to “fact based public discussion” and the shared expectations required for nations talk to each other about mutually beneficial common goals.

Their short-run incentives are completely at odds with the long-run interests of all of the rest of us.

2: Improving resilience to food system shocks

I’ve been waiting for Professor Tim Lang’s report on UK food security for the UK’s National Preparedness Commission to arrive since I saw him present on it to a meeting of the Agri Foods for Net Zero group last month. Now it has arrived, it is vast—even the executive summary is 52 pages. (The whole report runs to almost 400 pages). No wonder, as said in the presentation, that it took him longer than he expected when he started out.

Tim Lang? This description from the website of EAT catches it:

Tim Lang has been Professor of Food Policy at City University’s Centre for Food Policy since 2002 [now Emeritus Professor]. He was a hill farmer in the 1970s and for the last 38 years has engaged in public and academic research and debate about food policy.

In writing it up, I’m mostly just going to work from the Executive Summary.

Just as an aside, I didn’t realise that the UK had a National Preparedness Commission, since there are few signs of it in practice as I look around the UK, and it seems completely disconnected from Whitehall activities such as the Government Resilience Framework, and government documents such as UK’s the National Risk Register. 1

Indeed, the NRR has only one food risk in it: supply chain contamination. This seems myopic to me.

The report captures the state of Britain’s food in a few swift brushstrokes early on:

Diets, supply and tastes have changed and become more used to more plentiful, diverse and a-seasonal food. Where the British buy from and what is purchased has changed. So have tastes and expectations. At the same time, access to food has become more dependent on fewer, larger suppliers, while still being subject to the vagaries of unequal incomes and living standards.

It sets out to understand what might happen if this status quo were disrupted, partly because it believes that we need to improve what it calls “civil food resilience”:

the capacity of people in their daily lives to be more aware of risks to food, more skilled in reducing unnecessary risks, and more prepared to act with others to ensure all society is well fed in and after crises.

This, in turn, requires infrastructure, skills and support. But perhaps there’s a need to test the case for the need for greater resilience before we turn to the steps that are needed to get us there.

In fact the report spends little time on this—again, it’s not much more than a sketch in the Executive Summary, and there but implicit in the full report. It’s not that it’s a difficult case to make, it’s just that the authors don’t really do it. I wonder if this is a gap.

One of the problems here is that over the past seventy years or so the UK has moved from a model where food security (and food production) was an important element of national policy, to one that assumes that food is an open international market and that it will always be possible to import food. A lot of public policy seems to be stuck in this assumption, even while the discourse among experts is that this open market model is breaking down, through multiple factors including climate crisis and changing geopolitics. (This is putting to one side the long term health crises caused by ultra processed foods.)

During his talk, for example, Lang mentioned that the reason that the Russians assaulted Mariupol early in the Ukraine war was precisely to disable Ukraine’s ability to earn revenue from exporting wheat.

The over-concentration of the food industry, and its consequences, were also seen during the pandemic, when supermarket shelves started emptying. When he was at the New Economics Foundation, Andrew Simms gave a Schumacher Lecture called Nine Meals From Anarchy which anticipated this by more than a decade.

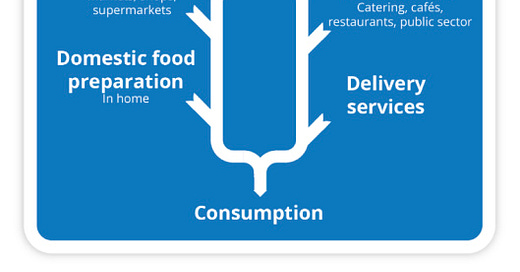

(Source: Lang (2025), Just in Case: narrowing the UK civil food resilience gap. National Preparedness Commission)

The report includes a useful schematic, in the same colours as a British motorway sign, that maps out the food system on route to reviewing its many vulnerabilities. A table lists out about 26 of these, if I counted them right, from “Extreme aggression e.g. blockade; destruction of food infrastructure” at the top to “Disinformation and fake news exposes limited public knowledge” at the bottom. No report is complete these days without a mention of disinformation.

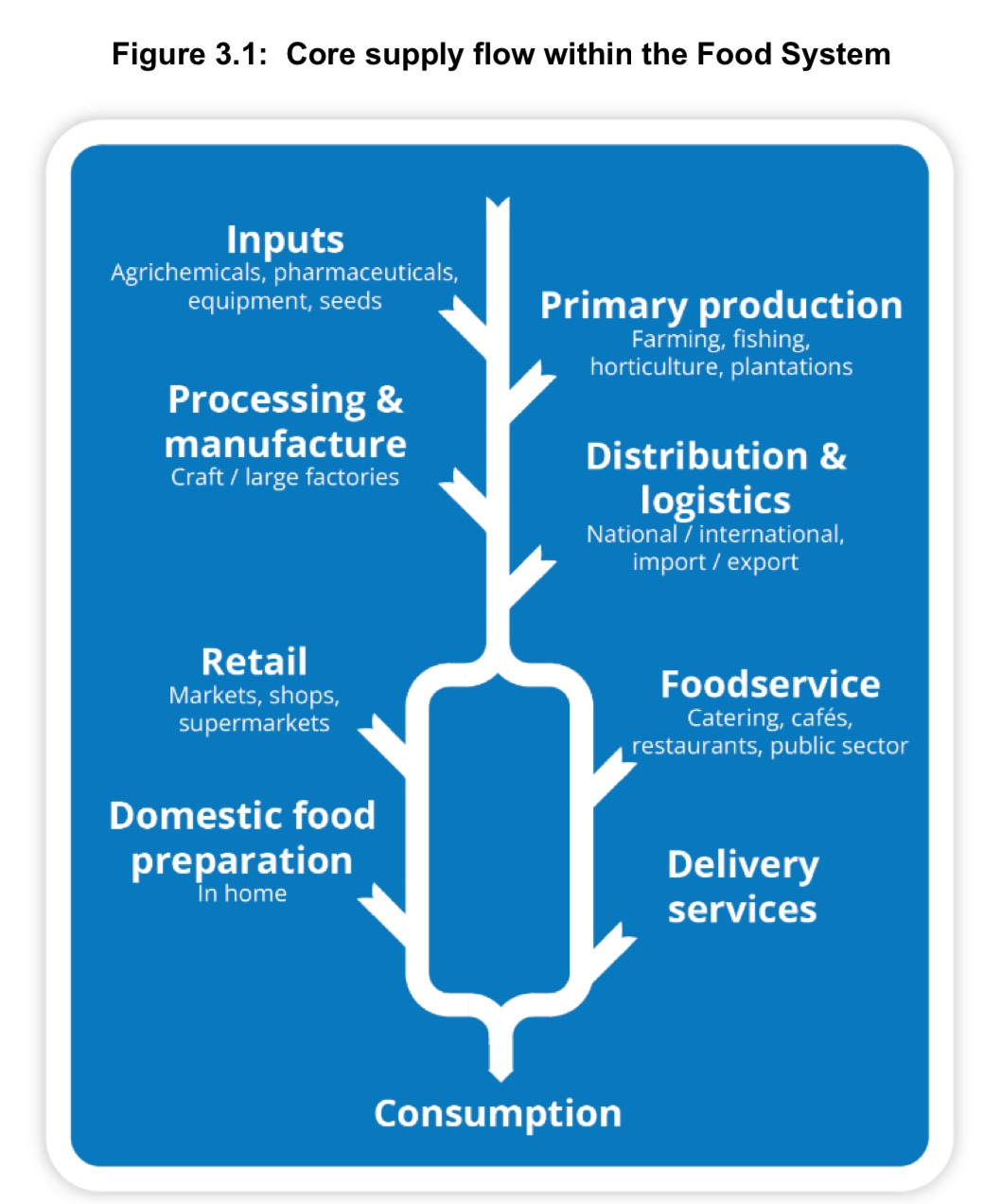

There’s a related table which tries to set out a typology of vulnerabilities, in terms of scale, intensity, duration and so on.

(Source: Lang (2025), Just in Case: narrowing the UK civil food resilience gap. National Preparedness Commission)

Both the report and the executive summary have a (recommended) discussion on definitions of resilience, which I’m going to bypass here, except to say that Lang settles on a three step cycle of ‘Prepare-Respond-Recover’, sourced from RAND. There’s a related discussion of the nature of networks, and how their design increases or decreases resilience.

But I’m going to cut to the seven steps the report proposes to build food resilience.

1. Learn from the other countries

There’s a lot been done elsewhere. Some of this is about making a distinction between how you respond to short term as opposed to long term shocks; some is about how you advise households to prepare to possible disruptions.

2. Assess the public’s mood, perceptions and engagement

A community focus is better than an individual response (we saw this in the way that US communities responded to the recent hurricane). Rationing may be necessary, but is not best done through markets.

3. Map the community’s food assets – ‘prepare, share, care’

This might include its ability to cook at scale, in the short term, and the ability longer-term to increase its growing resources. Wales, unlike England, has revived its horticulture sector through skills development and other actions.

This feels like it might be a good thing to do anyway, to try to reduce dependence on Big Food and its many adverse outcomes.

4. Local authorities are key to building civil food resilience

There is already a lively food culture in many local areas. But local authorities lack the powers to plan for food resilience in their areas, and need legislative changes to be able to do this.

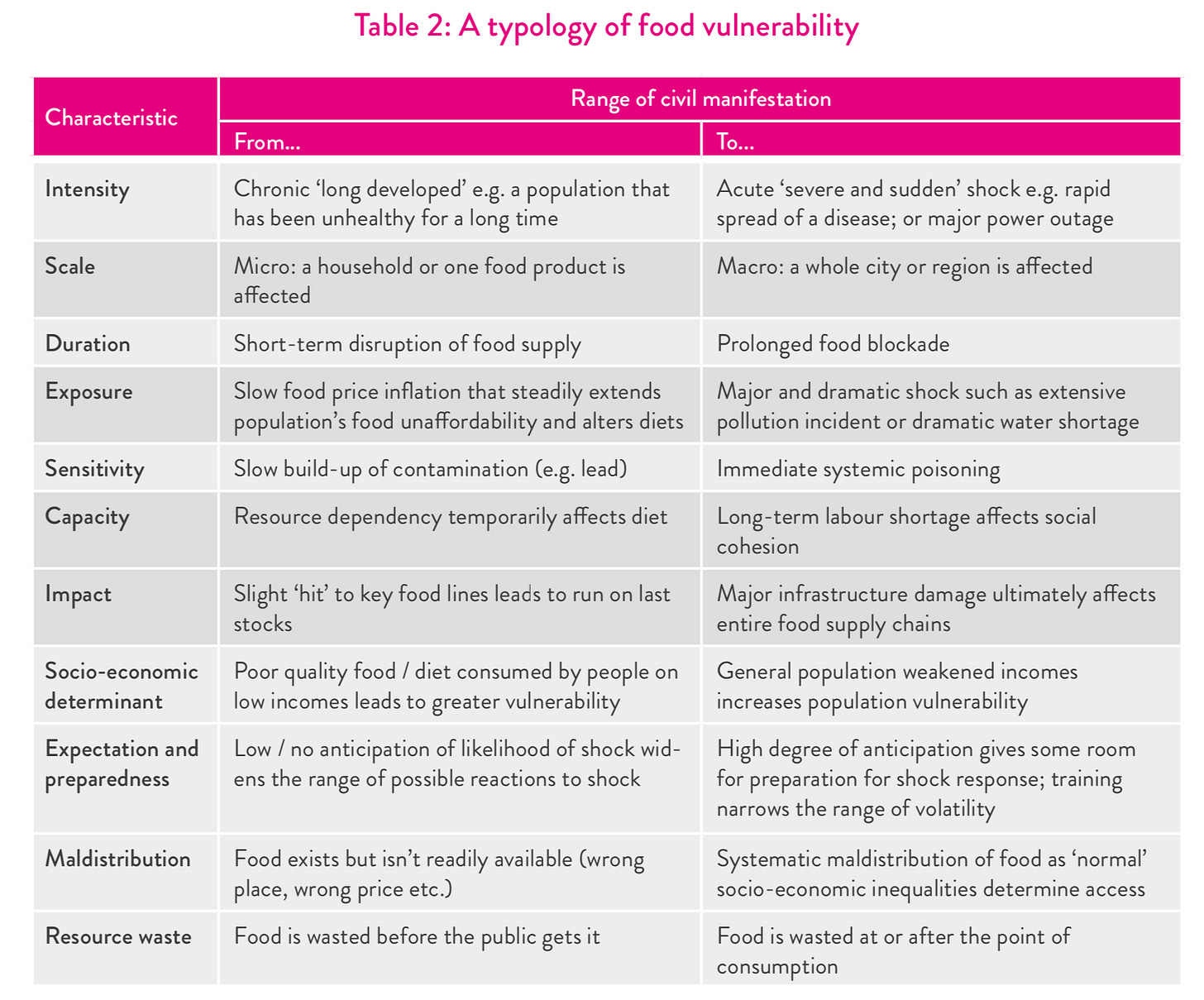

5. Create local Food Resilience Committees to co-ordinate resilience preparation

The UK actually has Local Resilience Forums, set up in 2004. They’re not currently very interested in food. But this means the framework is there if you want to use it. The authors think, though, that it’s better to create new local Food Resilience Committees, which has a certain Wold War II air to it.

(Source: Lang (2025), Just in Case: narrowing the UK civil food resilience gap. National Preparedness Commission)

6. The UK Central State must create and maintain a coherent food policy

Ha!... Seriously though:

A national food policy is overdue but urgently needed. This should provide clear goals, guidelines and indicators on many of the issues raised by the report. It should also improve cross-UK and multi-level co-ordination between existing ministries, agencies, regions and local authorities. Currently, local authorities have no legal obligation to ensure people are fed in crises, yet co-ordination of different ‘actors’ is urgently required to build civil food resilience.

Sweden seems to be an example worth following here.

7. Re-set the Government Resilience Framework for food

It’s just plain incoherent at the moment. Here’s the proposal in the report of what this might look like. We have a Government Department with ‘Food’ in its title, so maybe it could start there.

(Source: Lang (2025), Just in Case: narrowing the UK civil food resilience gap. National Preparedness Commission)

Sadly, you just know that doing anything about all of this will take a crisis—just as the Blair government in the 2000s government only introduced after truckers blocked motorways in protest against rising fuel prices.

On the other hand, doing all of this might also help to improve food policy overall—not just increase our food resilience in case of shocks.

Other writing: music

I was a big fan of Marianne Faithfull, who died last week at the age of 78. I was able to write about her at the folk music site Salut! Live, where I am a contributor. Here’s an extract:

From 1967 to 1970 Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull had a four year affair—she had left her husband for him—and they were a showbiz glamour couple always in the full glare of the British press, not always for the right reasons. The Rolling Stones’ boys club wasn’t perhaps the best place for a young woman to be in the late 1960s. She had to go to court to get her co-writing credit for Sister Morphine, and then there were the drugs.

When it fell apart, she fell hard. A miscarriage and a suicide attempt didn’t help. She ended up as a heroin addict on the streets of Soho before friends pushed her into treatment. Her return to music at the end of the 1970s was described by Vulture as “one of the most striking second acts in the history of music”. Broken English is a post-punk classic that seems to channel all of the distress of the previous decade.

j2t#629

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

There’s a reason for this. From its website: “The National Preparedness Commission (NPC) is an independent and non-political body, whose fundamental objective is to promote policies and actions to help the UK be significantly better prepared to avoid, mitigate, respond to, and recover from major shocks, threats and challenges.”