5 September 2024. Misinformation | Drugs

Most of what we’re told about misinformation is wrong // Hacking Big Pharma—the anarchist approach [#599]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Most of what we’re told about misinformation is wrong

A column by Tim Harford in the Financial Times suggests that most of the things we think we know about misinformation are wrong. Here’s his summary of the current conventional wisdom about misinformation:

misinformation — or perhaps Russian disinformation — is everywhere, that ordinary citizens are helpless to distinguish truth from lies, and furthermore that they do not want to.

As a line of argument, this emerged after the annus horribilis of 2016, the double whammy of Trump and Brexit, and the sight of Putin smirking in the wings.

But Harford has been reading an article in Nature by Ceren Budak, Brendan Nyhan, David Rothschild, Emily Thorson and Duncan J Watts that says that this is basically not true. The story about misinformation is much more specific than this.

This is a credible group of researchers, and their article was published in June, but behind the very aggressive Nature paywall. (I know that Nature has a business model to protect, but it also makes claims to have an interest in the public interest, which is why they publish some pieces free-to-air. On an important matter of public policy such as this, especially in the year of scores of elections, you’d have thought that putting this article in front of the paywall had crossed their minds).

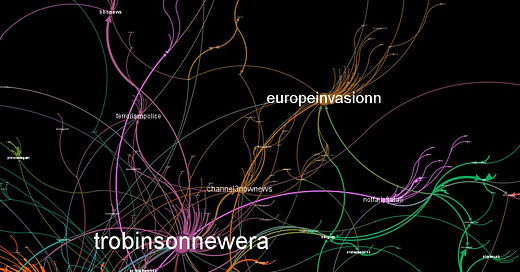

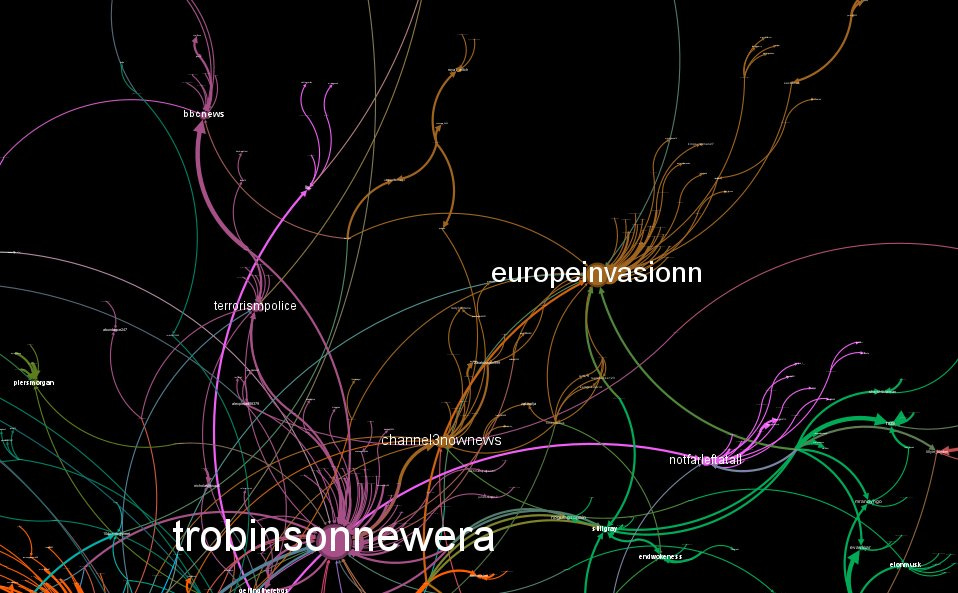

(How misinformation is organised: analysis by Marc Owen Jones of post-Southport anti-Islamic posts.)

In the publicly available abstract to the article, the researchers have their own version of widely held misconceptions about misinformation that are not supported by evidence:

that average exposure to problematic content is high, that algorithms are largely responsible for this exposure and that social media is a primary cause of broader social problems such as polarization.

Their research, which is based on a review of behavioural science research into misinformation, suggests instead that:

in general there is “low exposure to false and inflammatory content”; and

that the viewing of such content is “concentrated among a narrow fringe with strong motivations to seek out such information”.

Staying with the abstract—indeed, milking pretty much all of the substantive content from it—this has immediate policy implications:

we recommend holding platforms accountable for facilitating exposure to false and extreme content in the tails of the distribution, where consumption is highest and the risk of real-world harm is greatest.

Although the Nature piece is tightly paywalled, the media arm of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania spoke to some of the researchers when the article was published, since Duncan Watts runs the CSS Lab at UPenn.

The article breaks out the main errors in discourse about misinformation, and expands on the policy proposals summarised above.

Misleading use of statistics

In a lot of the discussion of misinformation there are eye-catching stats about the volume of misinformation. In practice, we live in such a sea of data these days that such figures represent tiny proportions of content:

For example, in 2017, Facebook reported that content made by Russian trolls from the Internet Research Agency reached as many as 126 million U.S. citizens on the platform before the 2016 presidential election. This number sounds substantial, but in reality, this content accounted for only about 0.004% of what U.S. citizens saw in their Facebook news feeds.

That’s not to say that the impact of misinformation is not large, as we saw in the highly targeted case of the Southport-related riots. (I wrote about that on Just two things here). But treating it as a problem of volume leads to the wrong policy conclusions.

Over-emphasis on the effect of algorithms

The narrative suggests that algorithms push harmful content towards people. The researchers found that the algorithms tended to push people towards more moderate content. Instead,

exposure to problematic content is heavily concentrated among a small minority of people who already have extreme views.

Further, they appear well able to seek it out, and to amplify it, as we saw in the case of the Southport riots.

Social harms

Again, the popular discourse suggests that exposure to misinformation on social media is the source of a number of social and political harms.

One of the researchers, David Rothschild, who works for Microsoft Research Lab, observes that because social media has a relatively short, two decade, history, it is possible to correlate it with a number of negative social outcomes in that time, but:

empirical evidence does not show that social media is to blame for political incivility or polarization.”

It’s worth going back to Tim Harford’s article at this point, since he references a study that looked specifically at ‘untrustworthy websites’.

Researchers constructed a list of nearly 500 “untrustworthy” websites operating in 2016, but of all the visits made to news sites by US citizens in 2016, this long list of dubious sources explains less than 6 per cent.

As Harford says, 6 per cent is still too much, but there’s a different problem here—public perception about the proportion of ‘untrustworthy sites’ is way out of line with this number:

A Gallup study in 2018 found that US adults believe 65 per cent of news on social media is misinformation. That suggests to me that we should be less concerned about people falling for fake news stories and more worried that ordinary citizens are cynical about stories that are trustworthy.

The good news from this research is that it turns it from a policy problem that is difficult to address to one that is much more straightforward. Apart from the “more research would be a good thing” recommendations here, two stand out, and they’re spelt out in the UPenn article:

Measure exposure and mobilization among extremist fringes

Platforms and academic researchers should identify metrics that capture exposure to false and extremist content not just for the typical news consumer or social media user but also in the fringes of the distribution. Focusing on tail exposure metrics would help to hold platforms accountable for creating tools that allow providers of potentially harmful content to engage with and profit from their audience,

Reduce demand for false and extremist content and amplification of it by the media and political elites

Audience demand, not algorithms, is the most important factor in exposure to false and extremist content. It is therefore essential to determine how to reduce, for instance, the negative gender- and race-related attitudes that are associated with the consumption of content from alternative and extremist YouTube channels.

And the second part of this is about increasing accountability among mainstream actors in amplifying misinformation:

As it happens, we’re watching an example of what all of this might mean in policy terms play out in front of our eyes at the moment, in Brazil. The story is a bit complex, and has become mired in some legal issues in which X has failed to comply with court orders. (Between them Counterpunch and Ryan Broderick have a reasonably good account). In essence the Brazilian Supreme Court has enforced a request to Twitter/X to suspend the accounts of seven prominent Bolsonarists who are accused of spreading misinformation and hate speech.

In that case, X’s failure to comply has meant that the Brazilian government has shut down Twitter.

The letter from the European Commissioner Thierry Breton to Twitter/X during the Southport riots (and ahead of the love-in between Musk and Trump on the platform) has the same import: we will regulate you if you don’t control hate speech and misinformation.

In other words, if the researchers are right about this, we can limit misinformation by using existing law. Given that Elon Musk covers his hard-right politics with a “libertarian” commitment to free speech, we’ll then watch Twitter go out, as in Brazil, country by country, across the planet. Facebook might be harder to deal with.

H/t to The Overspill.

2: Hacking Big Pharma—the anarchist approach

Four Thieves Vinegar Collective is an anarchist group that has spent a number of years teaching people how to make cheap DIY versions of pills that can help cure or manage health conditions. They are basically anarchist chemists. They are based in the US, so the market cost of these pills is often hundreds of times higher, even if your health insurance company is willing to pay for them.

The collective calls this “a right of repair for your body.” On its website it describes its purpose as

“enabling access to medicines and medical technologies to those who need them but don’t have them.”

Obviously I was attracted immediately by the collective’s name. The article, in 404 Media, is by Jason Koebler: his principal interviewee for the piece is Mixael Swan Laufer, the chief spokesperson for the group. Even anarchists need some structure.

(Mixael Swan Laufer onstage at DEFCON32. Photo: Four Thieves Vinegar Collective)

And this is also a trend that one has been able to see coming for a number of years now, as the cost of digital tools has fallen and biochemistry has become more digital. I think I first discussed this in a project on drugs that I ran for UK Foresight in 2004.

All the same, the US numbers are staggering. Laufer uses the example of a drug called Sovaldi, which cures hepatitis-C. The course of treatment runs for 12 weeks—you take a pill a day during that time—and the pills cost $1,000 each. So if you have $84,000, this works fine. Unsurprisingly, insurance companies prefer to pay for the cheaper drugs that suppress the condition rather than curing it. Forms of rationing based on cost exist in all health systems, of course: they are just more visible, and more stark, in the US.

The Collective decided to see what it would cost to make a pill that had Sovaldi’s properties, and came up with sofosbuvir:

Chemists at the collective thought the DIY version would cost about $300 for the entire course of medication, or about $3.57 per pill. But they were wrong. “It’s actually just a little under $70 (83 cents per pill), which just kind of blew my mind when they finally showed me the results,” Laufer said. “I was like, can we do the math here again?”

Hepatitis-C kills about a quarter of a million people worldwide each year.

Similarly with the abortion drug misoprostol, now hard to obtain in some US states following the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling. Normal cost is $160; it can be manufactured for 89 cents.

So what are they doing here? Well, the first thing is, they’re not selling anything themselves:

Instead, they are helping people to make their own, identical pirated versions of proven and tested pharmaceuticals by taking the precursor ingredients and performing the chemical reactions to make the medication themselves.

There’s an explanation of some of the ways they do this in the article, and also on their website, but in summary they are building a set of tools that helps people figure out for themselves how to create the open source drugs that they need but can’t afford.

These have catchy titles: Chemhacktica is a forked version of an MIT-DARPA project that uses machine learning to map out chemical pathways for molecule synthesis; the Microlab is an open-source piece of lab equipment that can assemble the drugs identified by Chemhacktica, which can be assembled from readily available parts for well under $1,000. The Collective has published detailed instructions about how to build this, along with the code to make it run.

There are some other building blocks on the site as well. The Apothecarium is a drag-and-drop recipe system that tells you how to generate a file that the Microlab can run, and gives step by step instructions to make specific medications.

The Collective’s intention is to put these out into the open and then disband themselves:

“Our ultimate hope is to get to a point where we’re no longer necessary because the notion of DIY medicine, no matter anybody’s opinion of it is common enough that if it comes up in conversation, someone can say ‘Oh I’m just going to 3D print a replacement.’”

Jason Koebler first heard about the Four Thieves Vinegar Collective in 2018, when he was editing a piece for Motherboard. As he explains in the piece, this is of more than professional interest—it’s not just “a good story”. In his 20s, a close friend of his who suffered from cystic fibrosis could not afford medication she needed for the condition, and she died at the age of 25. He wrote about this in an article in Vice. In the 404 article, he says:

At the time, a miracle drug called Kalydeco had recently been approved for use on some patients with cystic fibrosis. It cost $311,000 per patient, per year.

He spells out the name of the drug to Laufer during the call, who puts the information into their tools, and tells him, during the course of the conversation, how you could generate an affordable alternative:

“What? This is a nothing molecule,” he said, pulling up the molecular structure of the drug on Wikipedia. “Look. You’ve got two benzine rings, an NH here, a second ring with an alcohol here, and then two ammonias coming off of it. I mean, that’s so fucked. Like, you can I could make that in a weekend.”

Of course, there’s a whole set of questions buried in here about the proper rate of return for research, and whether pharma companies would ever develop anything if cheap copies were immediately available. And there’s another set of questions about the impact of cheap information and processing power on the traditional pharma sector business model. Obviously Laufer knows where he stands on this:

“We are hitting a watershed where economics and morality are coming to a head, like, ‘Look: intellectual property law is based off some ideas that came out of 1400s Venice. They’re not applicable and they’re being abused and people are dying every day because of it, and it’s not OK’.”

As it happens, when you read the history of Kalydeco on Wikipedia, it turns out that a lot of the research costs were put up by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, although the company insists that it spent billions of its own money to do the research as well. But often, when it comes to drug patents, you discover that much of the research started out in public and non-profit institutions.

James Boyle, who wrote the definitive book on the public domain, argues that this is a problem of power and politics. “Intellectual property”—the metaphor is telling—is supposed to balance the private benefit of financial return with the public benefit of open access to knowledge. But as he says:

“One of the most stunning pieces of evidence to our aversion to openness is that, for the last 50 years, whenever there has been a change in the law, it has almost always been to expand intellectual property rights.”

The reason for this:

[W]e have a problem of attention asymmetry in which interest groups whose business is threatened by new technologies and open sharing pay close attention to intellectual property law and work to ensure it promotes their interests... the countervailing motivations to preserve a robust public domain are relatively weak.

As for Laufer, he finds that the best way to get attention for the work of the Four Thieves Vinegar Collective is to stand on stage at hacker conferences and commit a number of federal felonies as he gives out anarchist-produced drugs from the stage.

A video of his talks at the hacker conference DEFCON 32 can be seen here (1h 16):

https://kolektiva.media/w/uvD1wWTRoh7HEto8zeSswr?start=3s.

j2t#599

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.