5 April 2022. Biodiversity | Energy

What if… climate neutrality is the wrong policy target? The geopolitics of energy

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: What if… Climate neutrality is the wrong policy target?

I wrote here yesterday about the EUISS project on assumptions—or more exactly, wrong assumptions. Their latest publication in this series is called ‘What If... Not?’. It comes with a handy visual aide memoire of a train plummeting off a half built bridge.

The three types of What If... Not? Assumptions they explore in the report are:

- Type one is ‘Policies we expect to work—but what if they do not?’

- Type two is ‘Illusion of certainty: what we expect to happen, but what if it does not?’

- Type three is ‘Surprise: what we not expect to happen, but what if it does?’

Yesterday I explored an assumption of the second type. Today I’m going to explore a Type one assumption—‘Policies we expect to work—but what if they do not?’

Specifically, this assumption is about climate change: ‘What if ... climate neutrality is not enough?’. It’s written by Yana Popkostova.

They have a standard format for each article: a 2027 ‘scenario’ (more accurately a vignette, since scenarios need to come in a set); a narrative from 2022-27; and then the vignette extends beyond 2027.

This story starts like this:

It should have been a morning of triumph. As of 1 September 2027, the EU had achieved its Green Deal gambit – three years prior to the 2030 milestone, greenhouse gas emissions had been reduced by 63 %. Yet, in preparation for her State of the Union address, Commission President Magdalena Wilsow... was not in celebratory mood. The latest op-ed by her former advisor filled her with foreboding. ‘Eschewing the moral imperative to protect nature is a fundamental definer of the Anthropocene. The hubris of climate leadership has eclipsed the failure to ensure stewardship of the environment. Quo Vadis, Europa?’

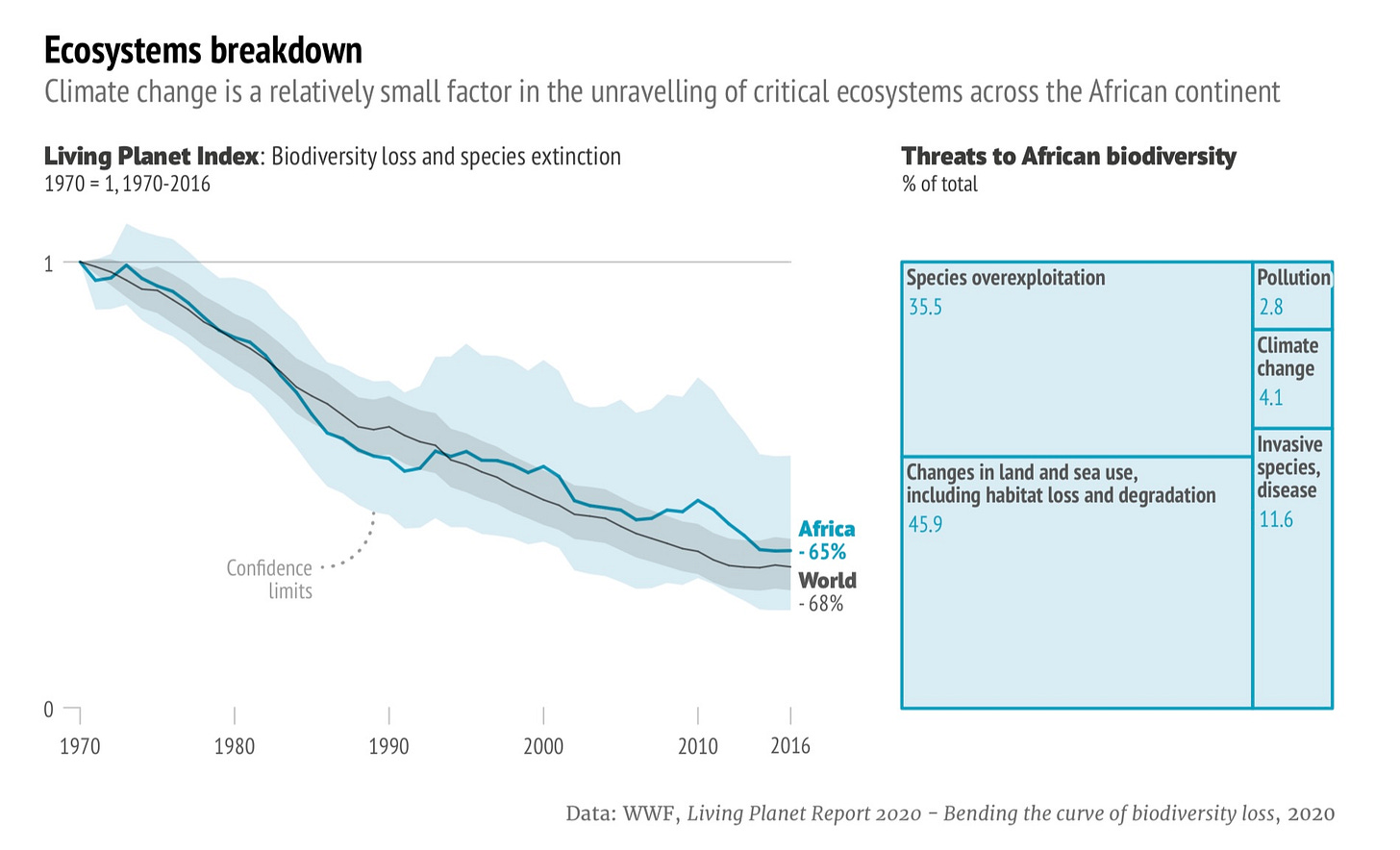

Leaving aside the thorny editorial question of whether any 2027 publication will be using ringing Latin phases in its editorial pages, the reason for this story is captured in a striking chart about African bio-diversity:

(Source: via EUISS)

And the 2022-2027 story is summed up in this paragraph:

(T)he notion that cutting CO2 emissions is just one, albeit indispensable, dimension of preventing environmental breakdown was routinely snubbed in global climate conferences from Paris to Glasgow and Sharm el-Sheikh. The preaching about carbon budgets and fixation on emissions targets disguised the sombre reality that planetary thresholds were being transgressed, stifling nature’s ability to regenerate.

The consequences are grimly predictable:

In 2027, clean technologies prevailed; renewable energy sources and electric vehicles were ubiquitous, heralding the end of the high-carbon era. Unfortunately, the corol- lary was the grim decline of nature and the stark disparities between the ‘Green haves’ and the ‘Green have-nots’. The low-carbon EU was surrounded by countries with broken ecosystems, demonstrating that emissions conditionality had not alleviated ecosystem degradation, undermining the EU’s creden- tials as a principled actor and exposing the shortsightedness of its policies.

Well, in the post-2027 scenario, they set about doing something about this: better late than never. By 2031 there has been the first COP on Environmental Integrity. The President makes a ringing speech quoting Rousseau, naturally, on the new social contract:

‘The social contract of the future goes beyond Rousseau’s dictum and makes nature the dominant party... over the past few years almost half a billion people have died because of our recklessness. The European Union pledges to give absolute priority to rebalancing our relationship with nature, humbly but with resolve.

But in some places bio-diversity had already collapsed. The pesky op-ed writer calls it ‘The clarion call that comes too late.’

The flawed assumption here is that: “Decarbonisation is the most effective way to prevent environmental degradation.” Which means that climate neutrality becomes the centrepiece of policy, and other planetary boundaries are ignored by policy makers.

As the saying goes: you might not be interested in the planet. But the planet isn’t much interested in you either.

2: The geopolitics of energy

The political scientist Helen Thompson has marked the publication of her new book Disorder by compressing her core argument about energy into a relatively short article in Nature. The article seems to be outside of the paywall.

The core story here is about the difficulty, and the likely length of the transition from fossil fuels to renewables. The length means, she says, that for the foreseeable future the geopolitics of fossil fuels will remain central to geopolitics.

For nearly 200 years, fossil-fuel energy has been central to geopolitics. The relationship between western Europe and China changed decisively in 1839, when Britain deployed coal-fired steam ships in the First Opium War. This move opened up China to a succession of imperial powers. The turn to oil in the twentieth century made the United States the world’s dominant power and began the decline of Europe’s great powers.

The consequences of energy-related conflicts can run for decades. She unravels the effects of the 1956 Suez crisis, when the US used its financial power to prevent Anglo-French action designed to secure European energy interests in the Middle East.

One consequence was that Europe turned to Soviet oil, now Russian, to secure its supplies. The legacy of that has been that dependence on Russian oil has muted European response to Putin’s expansionism. She doesn’t say this, but you can argue that in this respect Ukraine has been relatively lucky that it was invaded at a point where renewables are the cheapest part of the energy mix and are scaling quickly.

Energy transition creates new types of conflicts. The US Senate refused to ratify the Kyoto protocol in 1997 because China had been excluded, and they thought it would disadvantage the US.

But it also creates new forms of co-operation:

Despite the deterioration in Sino–US relations from around 2010, president Barack Obama struck an emissions agreement with Chinese President Xi Jinping in November 2014, which was the essential prelude to the Paris climate accord the following year. Yet even this moment of US–Chinese cooperation could not transcend geopolitics. In the same year, Xi also reached an agreement with Putin to build the Power of Siberia gas pipeline.

The fear that China will take control of the renewable age, in the same way that the US controlled the oil age, has been a visible element in American politics for close to two decades now. One reason for this is that renewable production is (currently) dependent on rare earth minerals. I say currently because there is continuing research into substitutes, and the ‘waste-landed’/ urban mining materials I discussed yesterday might also help. Be that as it may, it’s fair to say that Deng Xiaoping, a former leader of the Chinese Communist Party, was being more than mischievous when he said, some years ago,

“The Middle East has oil and China has rare earths.”

And, of course, in 2010 China blocked access to rare earths in a regional dispute with Japan, perhaps just to remind everyone else that it could. And since in geopolitics every action has consequences, Japan has spent the last decade making sure that doesn’t happen again.

Whichever way it plays, both fossil fuels and their substitutes will continue to play out in geopolitics for decades to come. Thompson concludes here article this way:

Quite simply, there is no way that governments — or the scholars who seek to advise them — can be serious about the energy transition without having a realistic strategy for the problems that history tells us will arise as the geopolitics of old and new energy sources and technologies combine.

She also discussed Disorder with her co-host David Runciman on one of the final episodes of Talking Politics before the podcast closed. I listened to this conversation a couple of weeks ago, and there’s a lot in it.

Other notes: I. M. Richard Moore

I was shocked to read last week of the unexpected death of the cycling journalist Richard Moore at the age of 49. He had beed a force for good in cycling, best known these days for being much of the energy behind The Cycling Podcast. Its coverage of professional cycling is exemplary, and it was also an early champion of women’s professional cycling.

I remembered that I’d written some pieces about his work: a review of his book Slaying The Badger, on the rivalry between Hinault and Lemond; on his book on the Tour de France, Etape, and coping with pressure; and an account of a talk he gave to my cycling club.

There’s an obituary at Cycling News.

j2t#294

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.