4 April 2022. Assumptions | Waste

How assumptions make for bad policy. Urban ‘mining’ starts to come of age.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: How assumptions make for bad policy.

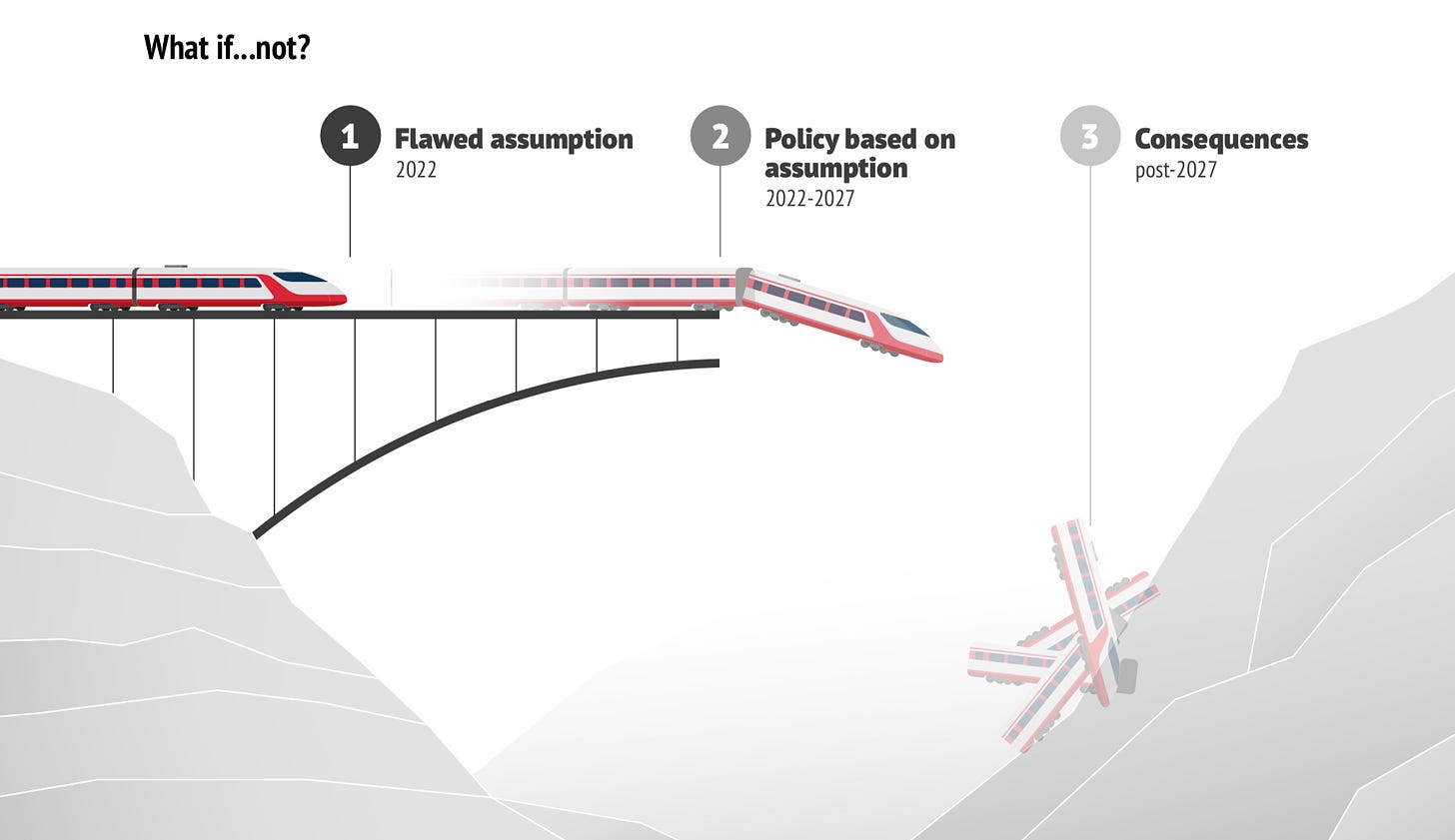

The European Union Institute for Strategic Studies has, over the past few years, been running an interesting series of publications on futures assumptions – and what happens if they are wrong. It comes with a helpful graphic of a train plunging off a half-built bridge, in case we don’t get it.

The series editor, Florence Gaub, the deputy director of the EUISS, describes the series like this:

we constantly make assumptions about the future and are therefore at risk of committing strategic blunders. That is because a massive 98% of our reasoning rests on automatic, effortless and unconscious thinking – what Daniel Kahneman has called ‘System 1’.

Of course, the reason we use System 1 thinking is to make the world manageable, cognitively. If we had to think everything through from first principles all the time, we would simply get overloaded. But of course, assumptions can be wrong.

An assumption is, after all, a belief that is not based on evidence, facts or proof. The very origin of the word is indicative of this: coming from the Latin word assumer, meaning to take up or appropriate.

Rather than "What if?" Questions, these pieces are about "What if… Not? ". What if something we believe to be true about the future turns out not to be?

The 2022 edition, called "The cost of assumptions", covers three different types of flawed assumptions.

- Type one is ‘Policies we expect to work—but what if they do not?’

- Type two is ‘Illusion of certainty: what we expect to happen, but what if it does not?’

- Type three is ‘Surprise: what we not expect to happen, but what if it does?’

In other words, these are all about different types of over-confidence about the future.

Each of the articles has the same format. There’s a little scenario ‘vignette’, set in 2027. There’s a narrative that projects the issue out from today to 2027. And then there’s a set of policy discussions on the implications for policy of the incorrect assumptions. There’s also a panel for each article listing the flawed assumption, the policy based on the assumption, and the consequences of this.

Two of the pieces in the report caught my eye, and I will come back to the second one, on climate change, tomorrow. Today I’m going to talk about Muslims in Europe. The article on this comes with a striking chart from The Guardian, showing 2016 data on how about the proportion of Muslims in European countries, and in the United States, is wildly overestimated by people in service, along with equally wild estimates on the future rate of growth.

This comes under the second type of assumption—the question is: What if there is no mass migration by Muslims to Europe?

The flawed assumption here is that there will be mass migration to Europe, mostly from the Arab world and Africa – and that this migration has negative consequences for European societies, and gives rise to populism. The policy that results from this is about the deterrence of migration designed to reduce migration generally. And the consequences of this, projecting forwards, is that European labour markets suffer shortages, with consequences for standards of living, tax take, social spending and so on.

These policies designed to appease anti-immigrant (and racist) sentiment didn’t even work. As the article, by Florence Gaub, notes,

Although these policies managed to keep my current numbers in check, they failed to weaken movements capitalising on anti-–migration rhetoric… Actors intent on stirring up dissent in Europe, such as Russia, continued to fan the flames by recognising migrants and orchestrating sustained disinformation campaigns.

She also notes that the policies were pursued even though

majorities of Europeans did not consider migration the most important policy issue. In some states, such as Italy, Poland, Romania and Spain, voters were even more concerned about emigration rather than immigration.

Obviously, writing this from Britain, we know quite starkly the costs of not making the case for the economic and cultural benefits of migration, of treating migration as a problem that needs to be deterred. The Brexit vote may have turned on the failure to do this over a period of years. The British Home Office (interior ministry) has also made “hostile environment” policies the cornerstone of government policy in the face of the evidence that it is destructive and harmful. And this is not just true in the UK, of course. It may just be more obvious here.

So it’s too easy to blame external actors, however malicious they might be. Such actors were only playing with the material they found to hand. In practice the story about Muslims in Europe is a deep narrative about the other, feeding off other deep narratives about race, religion and difference.

Trying to make policy differently in an area that feeds off worldviews and deep metaphors requires different stories. Our ageing populations and declining workforce numbers need more effective approaches to immigration. But we’ll need new metaphors first.

2: Urban ‘mining’ comes of age at last

About 15 years I did a strategic futures for a global mining company. One of the things I learned was that the cost of extracting gold from rock was steadily rising, while the cost of extracting gold from waste—such as mobile phones—was steadily declining.

One of our long-run questions for the business was whether it needed to position itself so that when those two lines crossed over, they were in a position to provide gold from such electronic waste—urban mines, as they were already being called then.

At the time, the Japanese were already making sure that waste with extraction value was being stored properly so that when the moment came they would be able to recover it.

All of this came back to me recently when I read that the Royal Mint plans to set up an ‘urban mine’ in Wales to get the gold out of mobile phones.

With e-waste estimated to reach 74 million tonnes by 2030, it’s thought that $57 billion worth of highly valued metals are being disposed of instead of reused. A single smartphone contains an estimated 0.035g of gold, depending on the model and date of manufacture, a spokesperson for the Royal Mint told IT Pro.

For the Royal Mint, this is both about reducing impact and ensuring a viable supply chain for its raw materials. Once the technology is scaled up, “the process will also be used to recover palladium, silver, and copper, which are also found in electronic waste.”

(Fairphone’s urban mine, 2011. Photo by Fairphone/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA)

In some ways it’s an example of “a future that has already happened”, in that we’ve just been waiting for the cost curve and the technology to improve.

All the same, there are significant challenges in making it work, which come down to the social and technical systems we have for managing products when they reach the end of their life.

There’s a helpful guide to all of this at Open Democracy.

Think about all the things you've put in the bin or taken to the tip over the past decade, then expand that quantity of waste by every business and home in your country. It’s a huge amount of stuff, containing a mishmash of materials, and it could have ended up anywhere. “What enables urban mining is well-sorted waste streams,” continues (Lund University researcher Jessika) Richter. “We should sort our streams at collection, as the more it is separated when we get it back, the lower the cost. Same with landfill – the more sorted the landfill, the easier it is to mine.”

There are organisations trying to help people to make sense of this. The WEEEforum (standing for ‘waste electronic and electrical equipment’ has an open access ‘urban mine platform’ that has data on stocks of such waste materials and who is using it. They’re not trivial numbers. There may be 450 million tonnes of ‘mineable products’ sitting in European homes and businesses. A lot of it is essential to an effective carbon transition.

Elements found in e-waste, such as gold, silver, platinum, indium and gallium, are not only expensive but essential for greener future technology, including wind turbines, solar panels and electric cars. If they end up in landfill, these materials can be highly hazardous, poisoning land and waterways.

But there’s always a but. In the UK, for example, the government’s ten year war on local authorities means that the local authorities haven’t got the time or the money either to educate people on electrical waste, or, increasingly, even run accessible waste facilities. It’s another reminder that austerity and outsourcing actively undermine attempts to take a holistic view of problems.

There’s also questions about the language of ‘mining’ for this exercise in more effective re-use. The Open Democracy writer, Tansy Hoskins, talked to Michelle Murphy, a Canadian activist who pointed to the violent and often exploitative relationships between mining companies and the communities they have to work with.

So the politics of language also matter. Murphy uses the phrase ‘waste-landed’ to break the link between this kind of urban recycling and the historic sources of the materials.

She’s not against the idea: she just wants us to recognise the power relationships involved.

“I could imagine a beautiful version of (urban mining),” Murphy says. “It would have to begin with: who lives there? What are the forms of governance and sovereignty and responsibility to the communities that live proximate to landfill? Can those places be turned into sites of beauty and value... What would it look like as a practice if the purpose was to meet the needs of the land, or to meet the needs of the community, as opposed to meet the needs of a manufacturer?”

Ukraine notes

I was intrigued by a story in the Guardian abut the ‘free Russia’ white-blue-white flag that Russian anti-was protestors outside of Russia have been carrying on demonstrations, so I followed it back to the Free Russia Institute, one of its sources. It’s essentially the Russian flag with the red ‘washed out’.

We want our protest against the war with Ukraine to be clear and visible to the entire world. We are Russians, but not supporters of this regime. We must find our banner, our unifying, symbolic, and non-contradictory assemblage point. And in the last week, in a number of communities of Russian emigrants, the idea of a new flag was born, which would become a unifying symbol of Russians who oppose bloodshed, who rally for a free Russia. This is a white-blue-white flag.

Why exactly that one? The tricolor is taken as its basis, but red is deliberately removed, as the color of the cult of blood, militarism, and red despotism. Many see it as a reference to Northern Russia, to free Novgorod, the veche proto-democratic Republic that challenged the Horde and Muscovites.

At Project Syndicate, Simon Johnson and Oleg Ustenko argue that the Ukraine war means that Russia is finished as a major energy power. (It’s tightly metered so you might have to get around a paywall.) Their argument in brief: that the war is accelerating the transition to other energy sources in Europe; that transitioning to Asian customers is a slow and complex process; and that while sanctions persist, Russia does not have enough of its own tanker capacity to ship its oil to new customers.

j2t#293

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.