31 October 2023. Turkey | Tech

Put out more flags: Turkey at 100 // The trouble with technological optimism [#509]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. If the email is clipped, please open it in Substack. Comments are open.

1: Put out more flags: Turkey at 100

By complete chance I find myself in Istanbul on the weekend that marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of modern Turkey. There are flags everywhere, some huge ones, including one that partly obscures the window of my hotel room.

(Anniversary cake in a window in Istanbul. Photo: Andrew Curry CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

There’s branding, of course, a little visual play on ‘100’ and the Turkish crescent and star. There are T-shirts. There is branded stationery.

There’s a street parade, and although it’s in another part of the city, we have seen streets blocked off and lines of police cars and fire trucks heading to join it. Later on Sunday there will be a desultory flypast, a naval parade on the Bosphorus, and—in case that seems rather old fashioned—a drone display as well.1

Many of the people heading for these displays carry flags, but discreetly, rolled up or wrapped around the handles of their bags. Some wore red to mark the day, a few the full red and white.

(Coming home from the parade. Photo: Andrew Curry CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In Taksim Square, there is a temporary pavilion showing a set of short films about Turkey’s last hundred years. I can’t follow the narration, but the iconography is unmistakable: speed, power, thrust, more power. One film, showing Turkey’s transformation in the past 100 years, is a relentless story of development and modernisation. It cuts from the black and white of the 1920s to the full colour 2020s. Roads, cars, infrastructure, medicine, armaments, but also soldiers, tellingly wearing the blue caps of the United Nations peacekeepers.

There is no narration to this: instead it is cut to the Turkish national anthem, sung by what might be an army choir.

We came across a similar pavilion, showing the same films, in a district of the city on the other side of the Bosphorus. I’m guessing that there might be sixty or more of these pavilions scattered across Turkey. People were recording the entire show on their phones.

There’s an obvious subtext here—so glaring that it’s barely a subtext at all. During 2022 and 2023, Erdogan has talked about the “Turkish Century”, with an implication that he is to 2023 what Atatürk was to 1923.

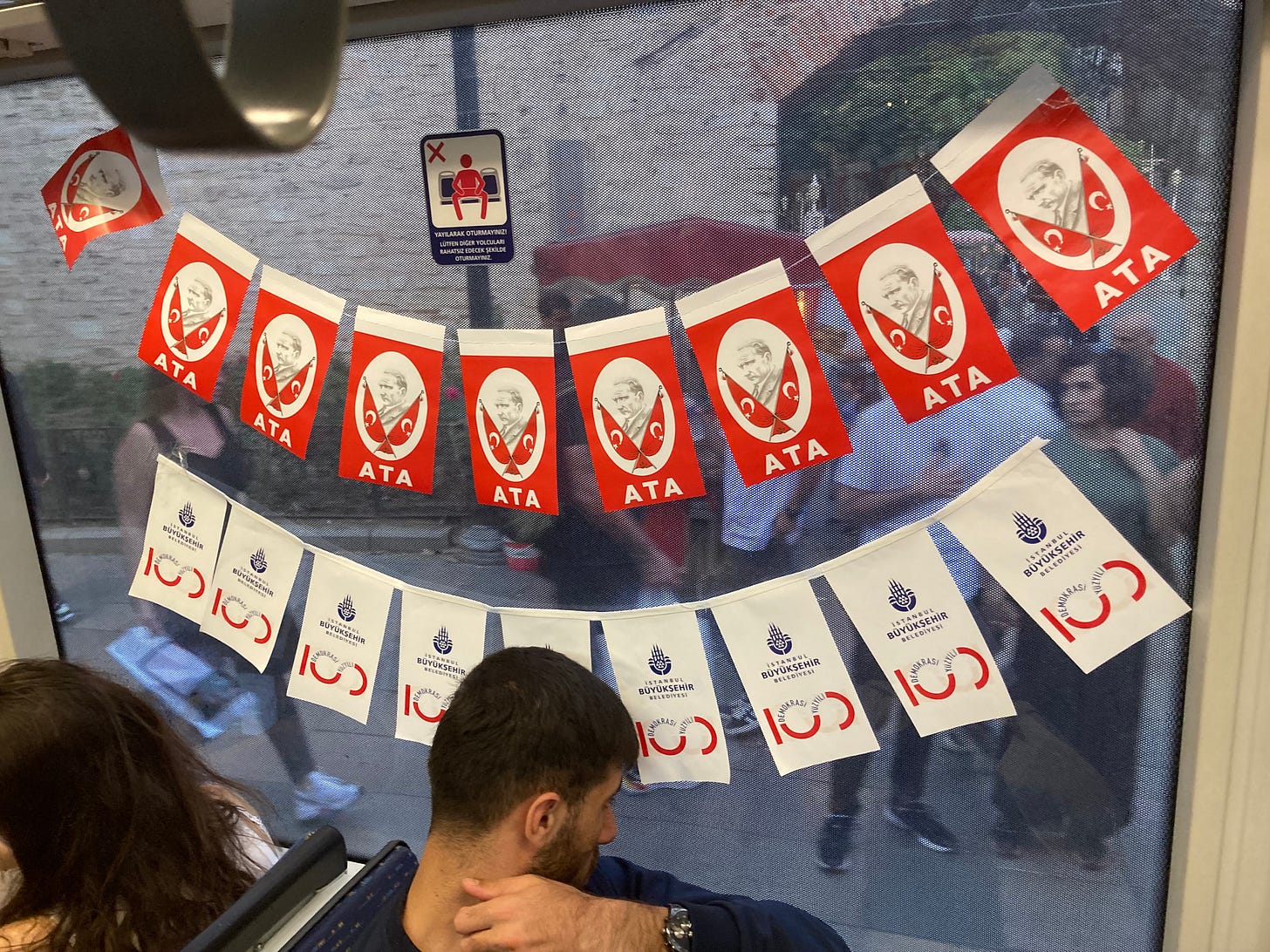

(Ataturk flags hung on the metro windows. Photo: Andrew Curry CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

I was told by someone who had lived and worked here that Erdogan isn’t really running against his political opponents: he is always running against the memory of Atatürk. The Al-Monitor journalist Amberin Zaman once described Erdogan as having “Atatürk envy”. And so, where Atatürk was merely the founder of the nation, Erdogan tries to be the leader of the region, a player on a world stage.

Hence, for example, his offers to mediate between Ukraine and Russia. This doesn’t always go so well. When he said last week that Hamas was not a terrorist organisation, the Turkish stock exchange slumped by 7%..

And of course, Erdogan has to run against Ataturk, for he is clearly not his political heir. Atatürk’s achievement in creating Turkey out of the ashes of World War 1, and starting its modernisation process, were formidable, as Hugh Pope explained in Politico earlier this year:

To reboot the country, Atatürk created a new culture for this new people, especially for those to whom this was a new land. Thus, an empire once ruled by a sultan-caliph became a republic with a nominal electoral system; the Ottoman language was stripped of Arabic and Persian loan words and switched to Latin script; Islam was demoted from the prime source of national identity in favor of an overbearing secularism; and Istanbul’s Byzantine cathedral of Aya Sofya — for centuries an Ottoman mosque — was symbolically turned into a museum.

Erdogan is a conservative nativist who is at war with many forms of modernity. He promotes Islam and is trying hard to put tight limits on democracy. He re-opened the Aya Sofya as a mosque, amid protests, and promoted the vast new mosque at Çamlıca, which can hold 62,000 at prayer and 100,000 in the aftermath of an earthquake.

Opponents have criticised the mosque as being unnecessary, but even so modernity has a way of creeping in. Çamlıca was designed by two Turkish women architects, and they deliberately ensured that it had good access and good facilities for women to participate in the life of the mosque.

In practice, it is hard to run against Atatürk. Conservatives may not like his secularism, but they value him as the founder of the state who defended Turks and and ended the sultanate. Liberals value his commitment to democracy and secularism. It is, for British readers, a bit like having a Churchill figure without Churchill’s terrible politics.

Like the other populist nativists, Erdogan’s base is in the country, not the city, the old not the young. These are shrinking political assets. The last election was closer than he seems to have expected, probably because inflation is running hot and the economy is suffering.

(Left: Erdogan’s image on the temporary pavilion in Taksim Square. Right: outdoor advertising: the headline reads ‘Century of peace’, according to Google Translate. Photos: Andrew Curry CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

All this has meant that the 100th anniversary celebrations were more subdued than they might have been. Erdogan’s decision to call a huge pro-Palestinian demonstration the day before almost seems like a deliberate distraction, according to some commentators. Others have suggested that the government was using the war in Gaza as an excuse to mute the celebrations. Much of the broadcast coverage of the anniversary was also cancelled, with Gaza as the excuse:

Turkey’s scaled-down centennial celebrations angered some citizens who believe Erdogan is glossing over the occasion to undermine Ataturk’s secular legacy in pursuit of his own political vision — and that of his religious support base... Still, many Turks held their own private celebrations, while opposition-run municipalities organised concerts and parades. Music, including a song that was written to mark the republic’s 10th anniversary, blared from cars adorned with Turkish flags.

A report in France 24 noted that there were few foreign guests here for the occasion, and quoted the Turkish academic Soli Ozel:

Erdogan "didn't really want to celebrate the republic," said Soli Ozel, a professor of Istanbul's Kadir Has University. "People are unhappy. Nothing has been done to create a festive atmosphere."

As Hugh Pope concluded in his piece earlier this year:

it is safe to say that for the foreseeable future, it is Atatürk’s image that will remain on every Turkish coin, banknote and office wall.

(Ataturk and the flag: Seen from the river. Photo: Andrew Curry CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

2: The trouble with technological optimism

I’m willing to admit that I’m going to be sceptical when one of Silicon Valley’s most successful venture capitalists feels the need to publish a 5000-word manifesto, as Marc Andreesen did recently, on his company’s website.

I don’t just think this because of the form of ‘The Techno-Optimist Manifesto’—a succession of paragraphs with short crossheads that scream “I’m being serious here”. The first eight cross-heads, in this order, are: Lies; Truth; Technology; Markets; The Techno-Capital Machine; Intelligence; Energy; Abundance. At the end, there’s a sequence that runs, The Meaning of Life; The Enemy; The Future.

(Source: a16z)

It’s also because the manifesto, as a form, is usually a shout from the edges. It is the sound of someone who wants the world to be different but has little voice to make it so. In Graham Molitor’s S-curve framework, they are trying to move a set of ideas or a worldview from the ‘Framing’ stage, where it is still a bit inchoate, into the ‘Advancing’ stage, where it can attract interest, and maybe adherents.

Think of, for example: The Communist Manifesto, the Manifesto of Surrealism, or more recently and much less famously, the Slow Thought manifesto.

Clearly this description of the S-curve positioning of the manifesto does not apply to Marc Andreesen. As Wikipedia states:

He is the co-author of Mosaic, the first widely used web browser with a graphical user interface; co-founder of Netscape; and co-founder and general partner of Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz... Andreessen is... an inductee in the World Wide Web Hall of Fame. Andreessen's net-worth is estimated at $1.7 billion.

In short, he’s not short of opportunities to speak, and the idea that digital technologies are transformational has been the dominant idea of our culture for the past thirty years or so.

But let me just take all of this at face value for a moment. Andreesen’s case is that people are railing against technology:

We are told that technology takes our jobs, reduces our wages, increases inequality, threatens our health, ruins the environment, degrades our society, corrupts our children, impairs our humanity, threatens our future, and is ever on the verge of ruining everything.... The myth of Prometheus – in various updated forms like Frankenstein, Oppenheimer, and Terminator – haunts our nightmares.

There’s a lot more “we are tolds” in this section, which are doing quite a lot of rhetorical work here. Those are the ‘lies’, anyway. Then there’s the ‘truth’. I’ve shortened this slightly, but left the layout the same:

Our civilization was built on technology.

Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential.

For hundreds of years, we properly glorified this – until recently.

I am here to bring the good news.

We can advance to a far superior way of living, and of being...

It is time, once again, to raise the technology flag.

The rest? In praise of growth, in praise of “free markets”, of the “techno-capital machine (“the engine of perpetual material creation, growth, and abundance”), against the “howling from Communists and Luddites” (which suggests that he understands neither of these), in favour of intelligence and Artifical Intelligence, in praise of a coming age of nuclear fusion, in praise of America, against Utopia, in praise of courage, in praise of the scientific method and the Enlightenment, in praise of competition, evolution and the truth.

“We believe” pops up a lot, and as in “we are told”, the “we” is also doing a lot of work here. It might be a reference to the “patron saints of techno-optimism” at the end of the manifesto, some of whom, were they alive, might be surprised to find themselves here. The first six, in a long list, are: Ada Lovelace; Adam Smith; Andy Warhol; Bertrand Russell; Brad DeLong; Buckminster Fuller.

But I’m not going to take you all of this way without dropping you off at the terminus. The last section, “The Future”, concludes like this (and this is the original formatting):

What world are we building for our children and their children, and their children?

A world of fear, guilt, and resentment?

Or a world of ambition, abundance, and adventure?

We believe in the words of David Deutsch: “We have a duty to be optimistic. Because the future is open, not predetermined and therefore cannot just be accepted: we are all responsible for what it holds. Thus it is our duty to fight for a better world.”

We owe the past, and the future.

It’s time to be a Techno-Optimist.

It’s time to build.

My feeds have had different views of all of this. The economics blogger, Noah Smith, liked it. This is his headline summary:

Marc focuses squarely on technology’s ability to bring abundance. And he appropriately frames abundance not just as “more stuff”, but as more choice in general for human beings, and more control over our world.

Smith has a sideswipe about “degrowth” later on, a position that he keeps mentioning but doesn’t properly understand. He came back to techno-optimism in an extended post a couple of days later. I don’t have space for much on this, but the post included a techno-optimist’s 2x2, seen in the diagram. Worth noting that although one of the axes is about positivist versus normative techno-optimism, this whole chart is very normative.

(Source: Noah Smith)

The tech blogger, Dave Karpf, didn’t like it:

Reading it felt a lot like walking past preteens wearing Nirvana tshirts or seeing an ad for the Frasier reboot: “Oh, have we decided it’s 1993 again? I guess I didn’t get the memo.”

Karpf, who has been reading old editions of Wired magazine as part of a research project, pointed out that both halves of this story—that “they” are lying to us and that techno-optimism is a panacea—are long-time Silicon Valley tropes. It’s also a long (and entertaining) piece, so let me just pull out a few lines:

Technological optimism has been the dominant paradigm throughout my adult life. We have spent decades clapping for Andreessen and his buddies. We have put them on magazine covers. We stopped regulating tech monopolies. We cut taxes for the wealthy... The sort of technological optimism that Andreessen is asking for is a shield. He is insisting that we judge the tech barons based on their lofty ambitions, instead of their track records.

So what’s going on here? The Read Max newsletter traces some useful threads—to Andreesen’s more conventional 2020 newsletter, ‘It’s Time to Build’, and to Silicon Valley tropes about ‘effective accelerationism’, or ‘e/acc’. After several years in which a16z has basically promoted crypto schemes, NFTs and other bits of digital froth, the manifesto, he suggests, is basically just marketing, in particular for a16z’s new ‘American Dynamism’ practice:

After a decade of high-profile failures and embarrassments, venture investing is no longer seen as credible or reliable. The political economy of the U.S. has shifted in labor’s favor, and economists and wonks are increasingly in favor of industrial policy as an engine of growth and stability... A V.C. confronted with this reality might both shift his strategy away from software platforms and crypto companies and toward the more reliable proposition of government contractors--and he might also grumble about all the people holding him back.

But maybe something more as well. Using Carlota Perez’ long waves model, we are clearly approaching the end of the information and communication technologies wave. As with all of these waves, we are at a point where the external costs are swamping the boat. We are also close to the end of the far longer wave of modernity. (Hardin Tibbs and I wrote about this in a paper after the financial crisis). And the external costs of this are literally starting to swamp everything.

And this is the best way to understand ‘The Techno-Optimist Manifesto’. It’s a howl from a rich and privileged man who senses that the world that has made him rich and privileged is moving on. But he doesn’t understand how, and he hasn’t got the time—despite his connections and his advantages—to stop and try to work out why.

j2t#509

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

My top travel tip, for anyone planning to go to Istanbul for the 125th anniversary, is not to travel on the tram that runs to the Bosphorus in the hour before the big event on the Bosphorus starts.