31 January 2024. Gender, again | Music

Unravelling the gender politics of young men // ‘Facing our reflections in the mirror of our cultures’. Remembering Martyn Bennett [#539]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Unravelling the gender politics of young men

There was some unfinished business in the piece on the gendered young people’s politics here on Monday, so I am coming back to it. I’ve also had a lot of comments, publicly and privately. ‘Young’ is 18-29.

So let’s start, briefly, with the politics of young women, radicalised in the last decade (in the UK, Germany, and the US), and the last half decade in South Korea.

In his FT piece and associated ex-Twitter thread, John Burn-Murdoch notes that this radicalisation isn’t just about gender issues. He uses attitudes to immigration as a measures for this:

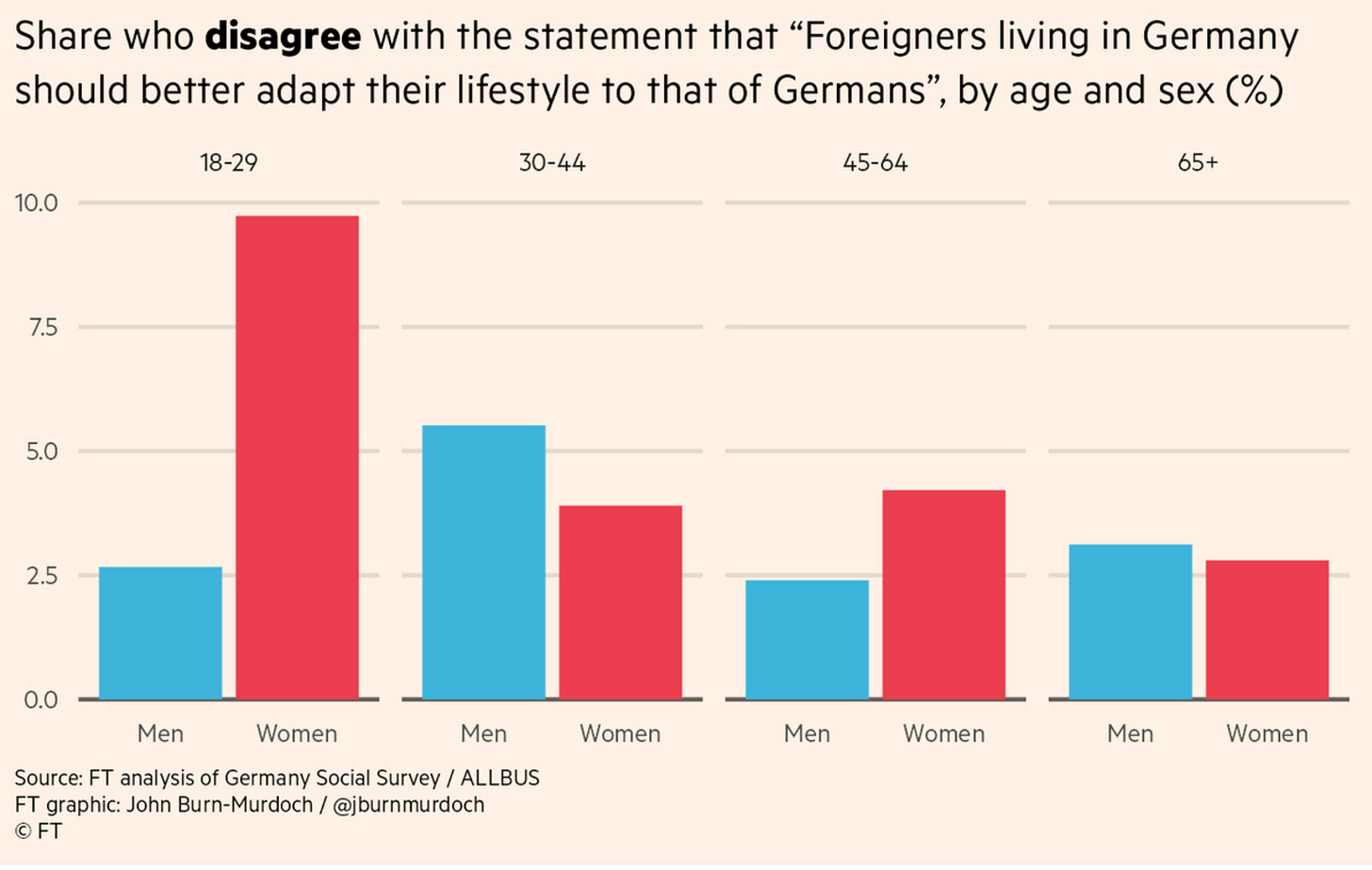

Young German women have become markedly more progressive on attitudes to immigrants, while young German men are more conservative on this than their elders.

Here’s the chart:

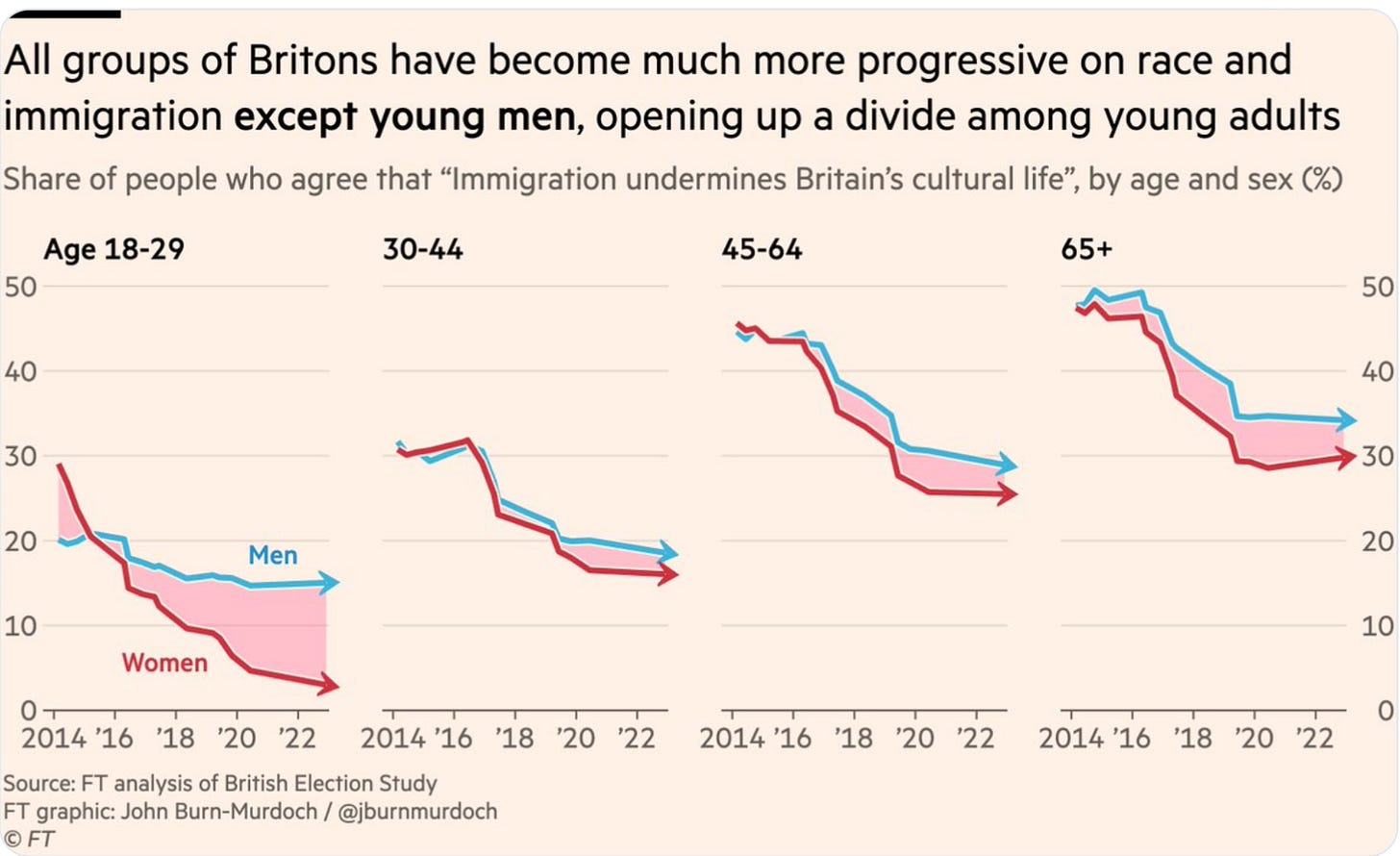

He sees a similar trend in Britain, well, sort of. This is what he writes:

All groups of people, young and old, men and women, have become more liberal on race and immigration except young men.

He calls this ‘remarkable’, although I think that British young men are getting a bit of a hard time here. Yes, young women have become almost completely progressive on immigration—the line almost goes to zero—and other cohorts have made similar progress, whereas the views of young men are much as they were six years ago. But they are still more progressive on the issue than any other cohort, except for young women.

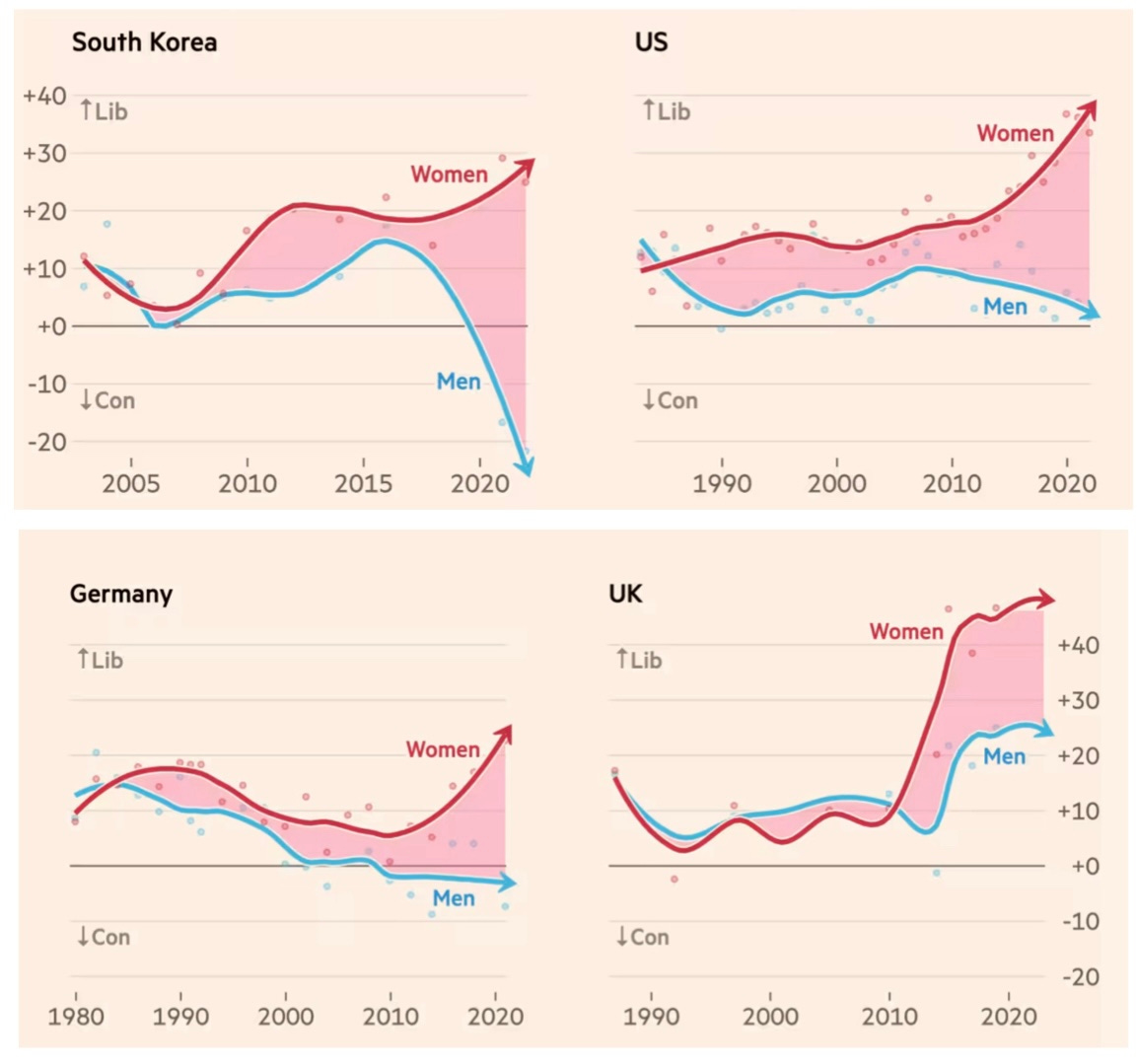

It’s worth going back to the summary chart that I shared here on Monday:

(FT graphic: John Burn-Murdoch / @jburnmurdoch. (C) FT

Looking at young men in Germany and the USA, they are around the average between being conservative and progressive for the country as a whole, while in the UK there has been a divergence in political views between young men and young women. I’ll come back to this, because I think there’s something salient here.

But the most detailed exploration of these attitudes is in the piece by Alice Evans that I referenced on Monday—I didn’t have space to get to her discussion of young men then.

In the section on the less progressive views on young men, she proposes four hypotheses, and then explores each of these:

Feminised public culture

Economic resentment

Social media filter bubbles

Cultural entrepreneurs, like Andrew Tate?

Feminised public culture

Summarising her argument: It is true that we have seen a more feminised public culture since the late 1990s, notably in some reasonably visible areas such as media, if not in other areas such as business.

As early as 1997, most of the editorial and sales executives at Time Warner were women . By 2000, women held 50% of US book copyrights . By 2020, they authored the majority of new books. Their readers were often female.

Just typing this makes you feel that this isn’t a strong hypothesis. It might explain some of the emerging conditions that make young women more progressive, but it doesn’t explain the increasing conservatism of young men.

Economic resentment

Evans writes:

A wealth of research suggests that economic stagnation fuels sexist resentment, xenophobia, far-right voting, and zero sum mentalities.

She cites a 2022 paper by Off, Charron and Alexander, which looks at ‘modern sexism’ among young men in Europe. They found that younger men are more likely to agree that

“Advancing women's and girls' rights has gone too far because it threatens men's and boys' opportunities”,

and that such resentment “is strongest among men who think that state institutions in their region are unfair, and live in regions with rising unemployment and acute job competition.”

This is connected to loss of status, which she has written more about here. In fact, in this other post, she calls status “the elephant in the room”. But the core finding is that,

Xenophobia and sexist resentment both reflect men’s unmet desire for status. A fundamental feature of patriarchy is that men want to have high status.

In turn, this is connected to the idea of “zero-sum” mentalities, which— no surprise—are more likely to emerge when you grow up in times of economic immobility and stagnation. Zero-sum attitudes mean that the only way I win is if someone else loses.

John Burn-Murdoch has done analysis in this in earlier work and the correlation is pretty stark:

Daniel Cox underlines this point in a piece in Business Insider on American men:

Out of a sense of increased insecurity, more young men are adopting a zero-sum view of gender equality — if women gain, men will inevitably lose. It's an outlook that makes them defensive, encourages them to ignore or overlook enduring challenges women face in society, and can even spur misogyny.

There’s not much on education in all of this analysis, although it seems like an obvious hypothesis to test. But the data that is here suggests that there is likely to be an educational effect here as well.

But it’s also worth noting that zero-sum politics aren’t necessarily right wing: “Eat the rich” is not right-wing slogan.

Social media filter bubbles

This is the obviously place to go, given the timings here, over the course of the decade from around 2010:

The big, structural shift that coincides with the growing gender divide is technology. … Algorithms elevate sensational, radicalising articles. They also create ‘filter bubbles’ (a term coined by Eli Pariser), by feeding people stories that appeals to their priors. This reinforces righteous resistance and group think… Polarised media fuels misperceptions and animosity.

Lewis suggests here that the effect of social media is to amplify small changes in views, in whichever direction. A perception that gender politics is unfair, combined with cultural echo chambers, would radicalise young women and do the opposite for young men.

Cultural entrepreneurs

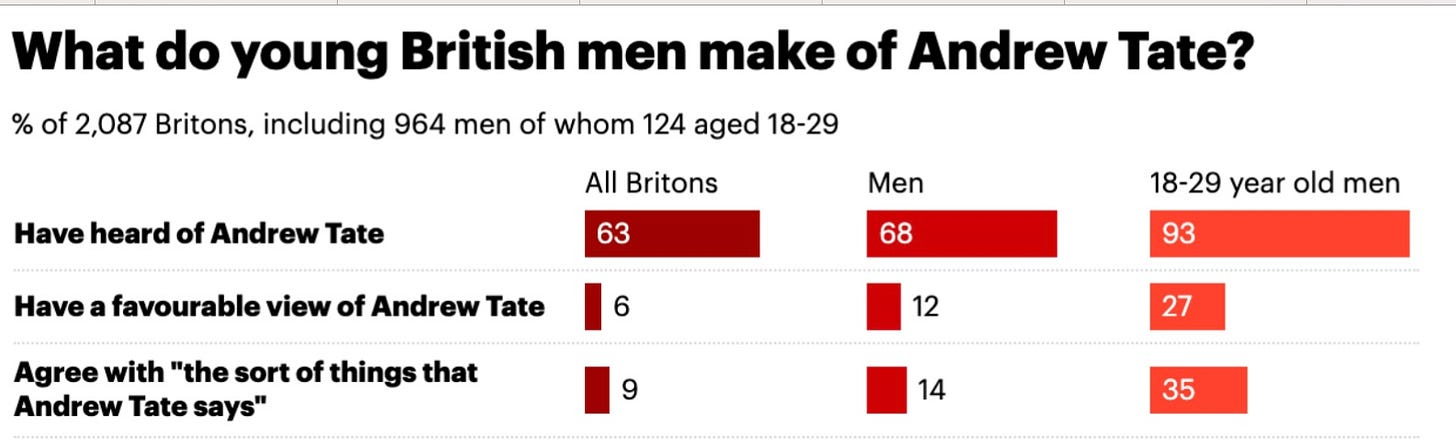

So, like zero-sum politics, social media filter bubbles and cultural echo chambers don’t necessarily head in one direction. But social media entrepreneurs can shape them in a direction that is both ideological and profitable. Lewis writes about the misogynistic influencer Andrew Tate:

A third of young British men now rate him favourably. As a multi-millionaire businessman - partying with attractive women in private jets and super yachts - he embodies many men’s idea of success.

(YouGov, 11-12 2023)

But it’s worth pausing at this point, because when you look at current voting intention by British 18-24 year olds (also courtesy of YouGov, literally published yesterday), we find that 58% of 18-24 year old women intend to vote Labour, against 55% of 18-24 year old men.

So one of the other issues here seems to be available political channels for resentment. Because in these various article, there are some stark polling and voting data. Voting intention data ahead of the recent Polish election, for example, showed that 46% of first time male voters (18-21) planned to vote for the far-right Confederation, but only 16% of women first time voters. It’s possible that the AfD performs the same role in Germany, providing a channel for resentment. In the UK, it’s possible that the lack of an outsider populist right party and the emergence of Corbynism has tempered attitudes among young men in the UK.

In a post reflecting on the Burn-Murdoch data, Robin James brings together some of these themes in a slightly richer way than I have managed here. (Thanks to Paul Raven for the link).

She connects contemporary financialised capitalism with the huge rewards to be gained through platforms for certain types of media spectacle, often around aspects of gender. She quotes the academic Sara Banet-Weiser’s on how“popular feminism” and “popular misogyny” are intertwined:

in the contemporary mediascape, popular misogyny increases in size and scope at the same time as popular feminism circulates more widely then ever before. We need to think of the call-and-response connection between them.

And James suggests—in a long piece that has a very specific focus, and some great links—that both the radicalisation of young women and the conservatism of young men have their roots in 21st century neoliberal politics:

In this economy, you have to appear like a good investment, and you can do that either by performing the identity of a historically marginalized group, or, if you’re not a member of one of those, by performing identity-based wounded entitlement. In this respect the girlboss and the alt-right bro are both privileged statuses, just on different ends of the spectrum of gendered vibes.

2: ‘Facing our reflections in the mirror of our cultures’. Remembering Martyn Bennett

(Martyn Bennett. Photo © by B.J. Stewart. https://www.instagram.com/bjstewartphoto/)

It was the anniversary yesterday of the untimely death in 2005 of the Scots-Canadian piper Martyn Bennett, of a lymphoma. He was only 33 at the time, but his short career flared like a comet across Scots music.

Looking back at his career, his impact was huge. An article by Jim Gilchrist on the BBC website 10 years after his death describes him as

'the techno piper', a dreadlocked iconoclast who took clubs and folk festivals alike by storm, combining his superb piping technique with a beefy sound system and an arsenal of beats and samples.

Bennett was born in Canada of a Welsh father and a Scots mother, the Gaelic singer and folklorist Margaret Bennett, and returned to Scotland with his mother after his parents separated. He was precociously talented, and played multiple instruments, including the violin.

But he was also a product of ‘90s culture, and his music drew on both the Scottish folk tradition and the beats and electronica of dance and trance music.

The result was a succession of innovative and intriguing records. His final record, Grit, on Peter Gabriel’s Real World label, is probably the most fully realised, even though he wasn’t able to play on it, but sampled his own playing and that of others. On the Real World site there is a short (28 minute) documentary of him working on the record, explaining how he works and how he thinks about music.

A Scotsman profile in 2002 quoted with some relish a review of his appearance at Cambridge Folk Festival in 2000, just before he was first diagnosed with cancer:

Scots music has never sounded like this before. No music has ever sounded like this before. Half the audience fled in fear of their lives.

The radical element here was the deep connection with the traditional sounds and voices of Scottish culture, especially Highland culture, and his willingness to embrace electronica, in all of its forms. Through his mother, and his childhood in the Scottish Highlands, he knew many of the singers from this culture, many of whom were quite old when he recorded them.

He talks about his attitude to this in his liner notes to Grit:

“GRIT is a serious artistic attempt to bring my own Scottish heritage forward with integrity… I find so many modern representations of Celtic culture careless and fanciful to the point that the word ‘Celtic’ has really become quite meaningless to me. As globalization is set to expand, I feel it’s time for us to face our own reflections in the great mirror of our cultures.”

(The remains of Hallaig. Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-SA-NC 4.0)

His breakthrough record was Bothy Culture, released on Rykodisc in 1998. One track on this, Hallaig, seems to capture both halves of his work. Hallaig took me by surprise when I first heard it, and it is immediately evocative, both ancient and modern. The song combines Bennett’s piping and playing and some effects with a reading by the Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean of a translation of his poem. Hallaig is, or was, a village on the Isle of Raasay, near Skye, that was emptied for sheep during the Highland Clearances. The translation is by Seamus Heaney.

The song is haunting enough that when I was in Skye in 2021 I made sure that we crossed the sound of Raasay to walk to the stones that still remain. There’s almost nothing there—except the stones that weren’t used to make the sheepfold, and the memory of the song, hanging in the air.

Three of Bennett’s records can be found in full on YouTube—Grit, Bothy Culture, and Glen Lyon, which is a collaboration with his mother. Bothy Culture and Grit are also on Spotify. There’s more information about him and his career at the website that is maintained in his memory.

(A version of this post is also published at the Salut! Live folk music blog).

j2t#539

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Very interesting both the Gender pieces. Couldnae RESTACK. Same with piece on Monday. I'm going to look up the Bennett music as it sounds fascinating