29 January 2024. Gender | Plastics

Young women are becoming more radical. Young men aren’t. // Trying to ban plastics runs into the fossil fuel lobby. That’s only part of the problem. [#538]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Young women are becoming more radical. Young men aren’t.

The data journalist John Burn-Murdoch is consistently one of the most interesting writers on the Financial Times—so much so that I currently have two pieces from him that are jostling for a place in Just Two Things.

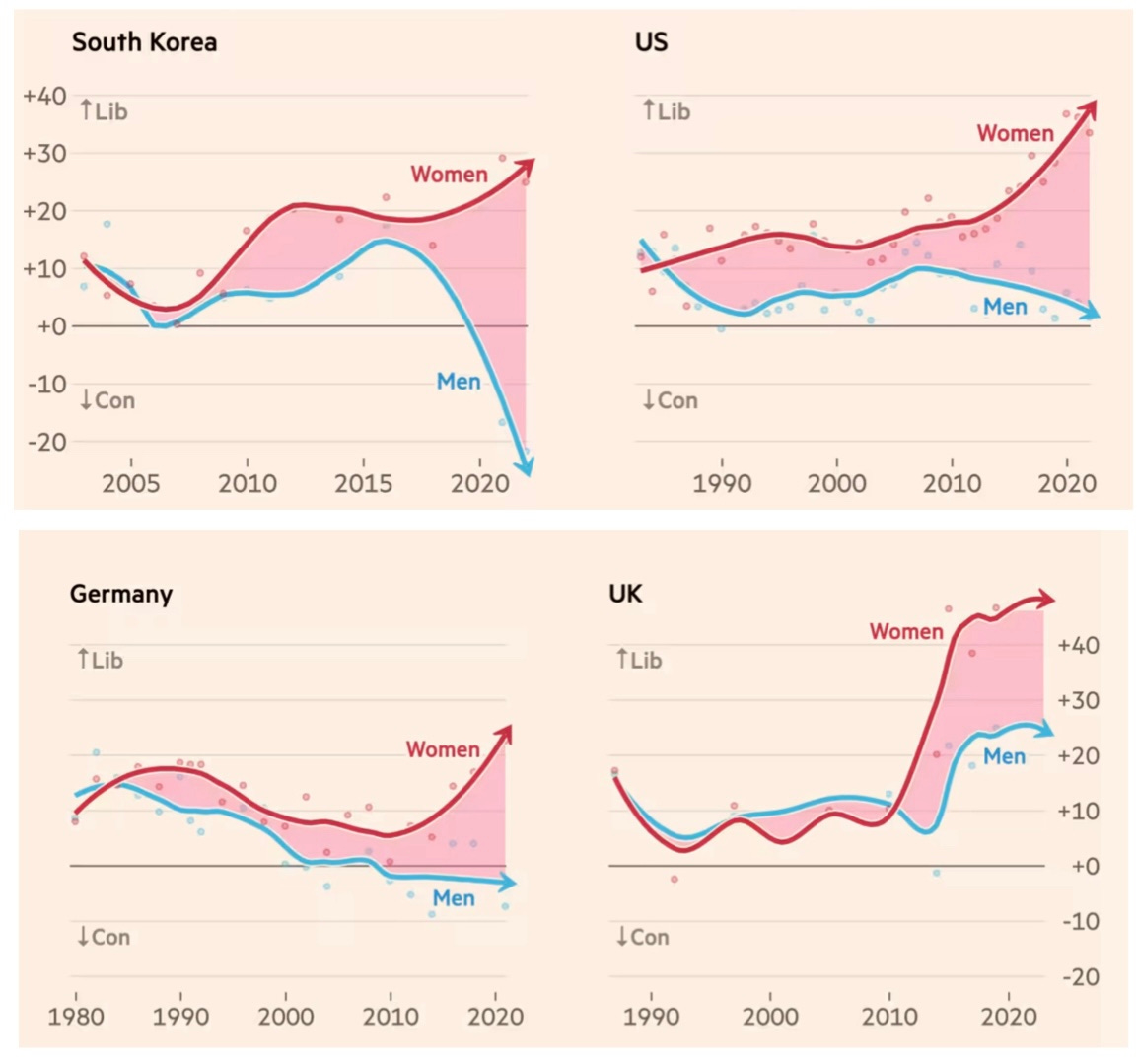

His FT article last week, which was also the subject of a long thread on ex-Twitter, points out some dramatic changes in political and social attitudes between young men and young women. In fact, this piece is likely to be mostly a set of charts. Here’s the headline data for the changing social and political attitudes of young men and young women, from 18-29 years old, in South Korea, the United States, Germany and the UK.

(Sources: Daniel Cox, Survey Center on American Life; Gallup Poll Social Series; FT analysis of General Social Surveys of Korea, Germany & US and the British Election Study. US data is respondent's stated ideology. Other countries show support for liberal and conservative parties All figures are adjusted for time trend in the overall population. FT graphic: John Burn-Murdoch / @jburnmurdoch. (C) FT)

Just for clarity, the data points at any moment in time show the attitudes of the 18-29 year olds at that time.

There are four elements in all of this that are immediately striking.

The first is that the gender divergence in attitudes is—in research terms—obviously significant. It’s around 25 percentage points in Britain, 30 in the Germany and the United States, and off the scale in South Korea.

The second is that, historically, as Burn-Murdoch says in his FT article:

One of the most well-established patterns in measuring public opinion is that every generation tends to move as one in terms of its politics and general ideology. Its members share the same formative experiences, reach life’s big milestones at the same time and intermingle in the same spaces.

The third, also historically, is that women’s attitudes have—certainly in richer countries—been more conservative than men. There are theories about why this was that may also be relevant to what’s changing now.

Fourth, this isn’t just about women. Something is going on with men as well, and not in a good way.

Burn-Murdoch’s explanation of this divergent is the #MeToo movement:

The #MeToo movement was the key trigger, giving rise to fiercely feminist values among young women who felt empowered to speak out against long-running injustices. That spark found especially dry tinder in South Korea, where gender inequality remains stark, and outright misogyny is common.

That might be true of South Korea, but just looking at the data for the US, Germany, and the UK, the divergence comes earlier, around 2010.

That women (of all ages) used to be more conservative than men was typically explained by their greater connection to the church and lower exposure to the workplace and social institutions such as trades unions.

In general, there have been signs that this has been changing for several decades. An article by Rosie Campbell and Rosalind Shorrocks in The Conversation quotes work by Inglehart and Norris from 2000, which described this as a generational process:

In this model, younger cohorts of women, who have experienced higher labour force participation, higher education, and less traditional gender roles, become more economically left-leaning, socially liberal and supportive of gender equality. This pushes them to the left of men in their party choices.

Looking specifically at the data on young women, it’s also clear that their more progressive views are not just about gender. Burn-Murdoch says:

In the US, UK and Germany, young women now take far more liberal positions on immigration and racial justice than young men, while older age groups remain evenly matched. The trend in most countries has been one of women shifting left while men stand still, but there are signs that young men are actively moving to the right in Germany, where today’s under-30s are more opposed to immigration than their elders

The best explanation for what might be happening here comes from Alice Evans’ newsletter The Great Gender Divergence. Burn-Murdoch thanks Evans, an academic, for helping him with his thinking and research, and in a piece published this week she offers a synthetic theory of those factors that might reduce gender divergence, and those factors that might increase it.

The factors that might reduce it:

Men and women tend to think alike in societies where there is

Close-knit interdependence, religosity and authoritarianism, or

Shared cultural production and mixed gendered offline socialising.

So these are at opposite ends of the spectrum—the first would lead to convergence around relatively traditional views, while the second would likely be more progressive. I haven’t the space to discuss this here, but she has a qualitative stories about Morocco, India, and Turkey in the article to discuss how the first works in practice, and about Catalonia for the second of these.

Increased gender polarisation might, she says, come from:

Feminised public culture

Economic resentment

Social media filter bubbles

Cultural entrepreneurs.

Here, she discusses South Korea and China as examples from Asia, and then a section using data from a set of Western countries. The critical question here is what’s happening with young men.

I’m going to have come back to some of the detail of this later this week, because the explanation is quite nuanced. For the moment, today, it’s worth noting a couple of data points from a couple of different countries about the attitudes of young men.

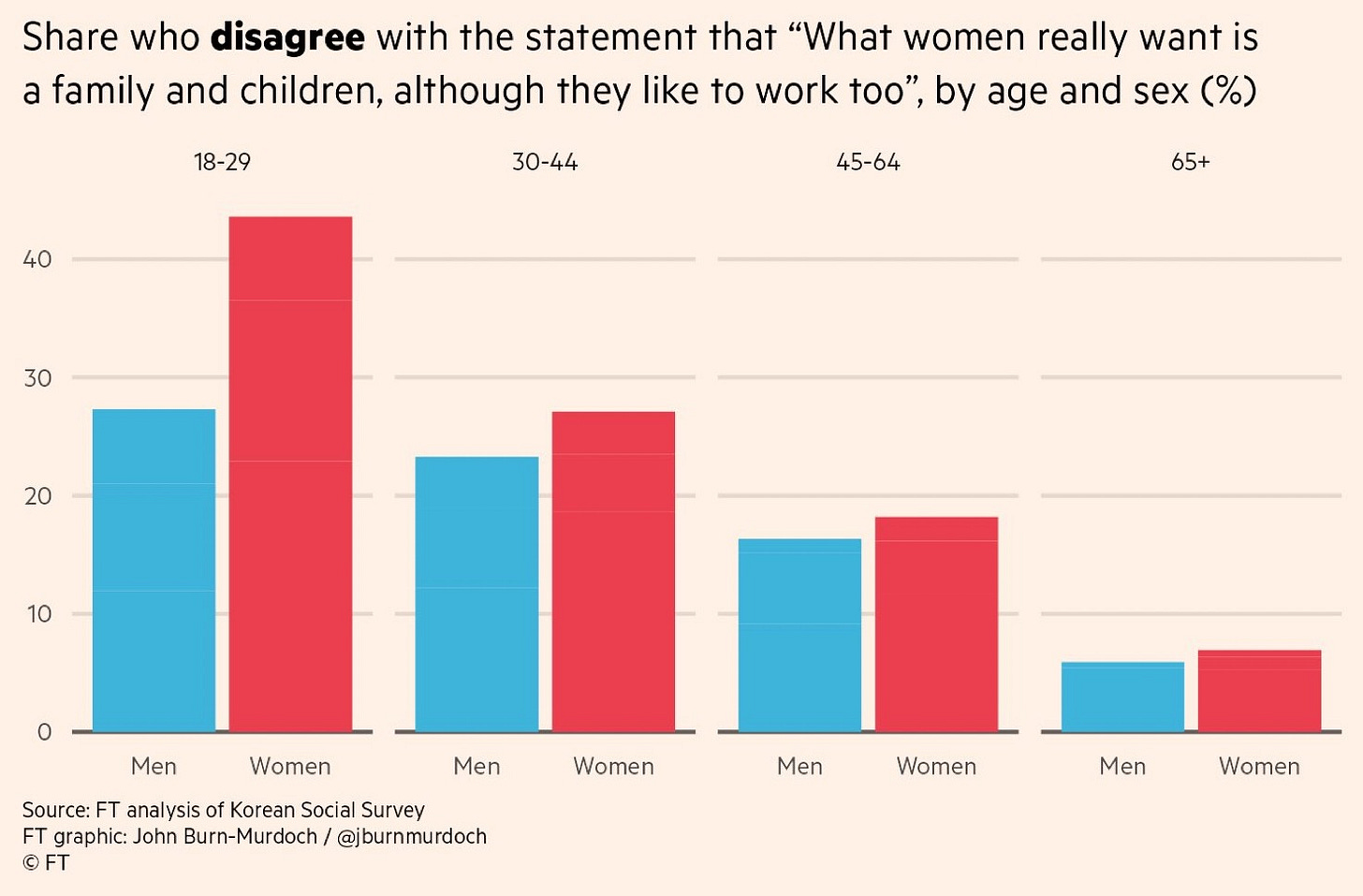

Here’s a survey question from South Korea about women and work:

Burn-Murdoch:

Here’s South Korea, where the ideology divide between young men and women is famously wide. Young women have become markedly more progressive on gender norms, but young men have not budged.

To spell this out: young men (18-29) are more likely to disagree with this than older men (actually, they’ve budged a bit), so this effect is not as strong as the headline divergence between genders in South Korea.

All the same, some of the effects might be far-reaching:

This is having huge impacts, including reducing rates of marriage and births in Korea, whose birth rate has plummeted to become the lowest of any country in the world.

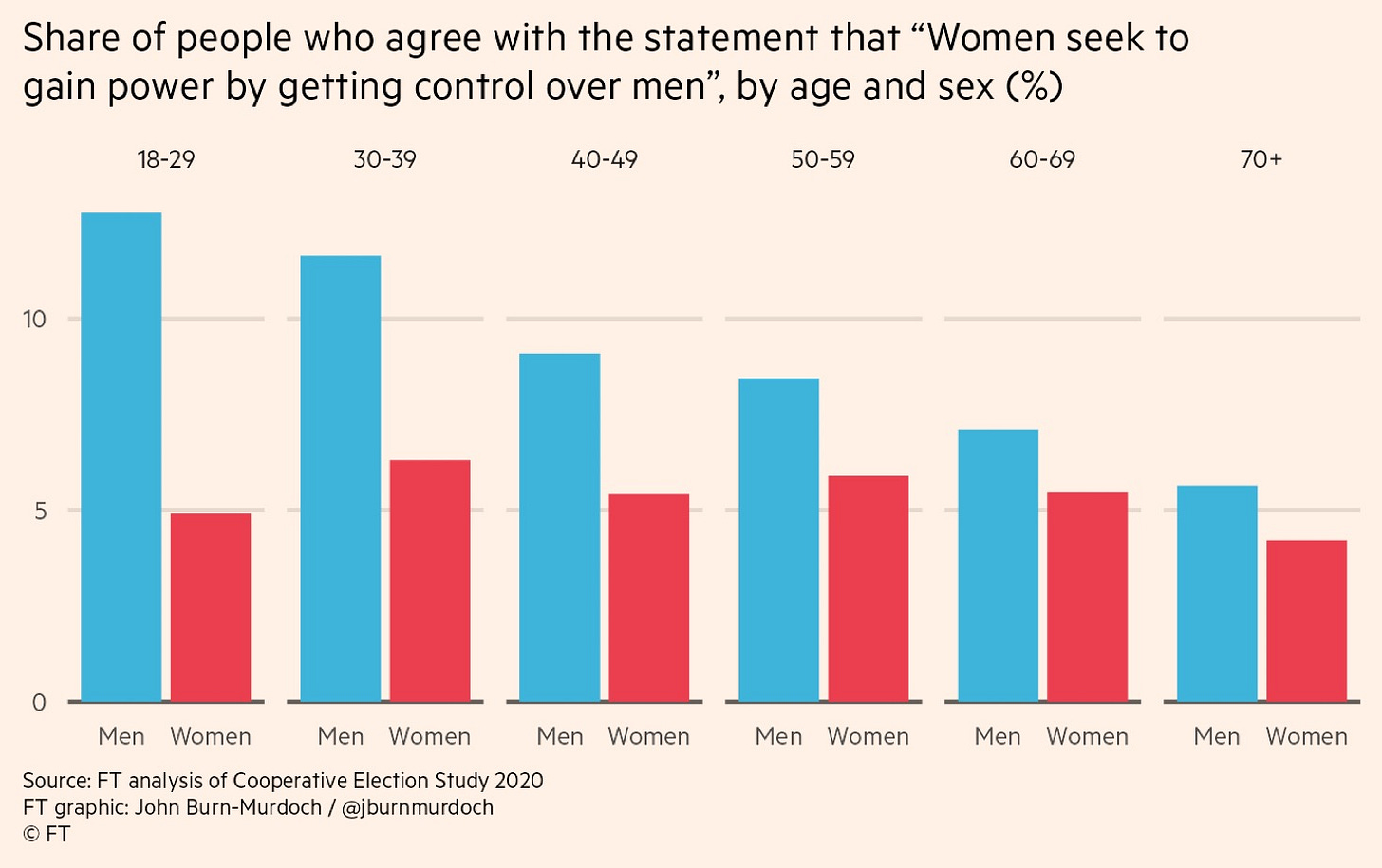

In the United States, in contrast—this is a very different question, and it’s worth noting that these are all relatively low percentage numbers—but all the same, young men are more likely to be more suspicious of women than older men.

It’s possible that these polarised views will start to converge again. But it’s also possible that they won’t. One of the other beliefs in the social attitudes literature is that, broadly, your attitudes about the world tend of harden as you move into your thirties.

But I’m still puzzled by the timing. What happened around 2010 that caused these similar effects in US, Germany, and the UK? I can’t help thinking I’m missing something obvious here.

(Thanks to Ian Christie for the tip.)

2: Trying to ban plastics runs into the fossil fuel lobby. That’s only part of the problem.

A couple of years ago Iwrote here about the agreement at a United Nations meeting to develop a binding treaty on plastics. It was, for those there, an emotional meeting and an emotional meeting. Two years on, however, and the environmental news site China Dialogue reports that things aren’t going well, despite the endless reports that say that plastics particles are now everywhere. (In the clouds above Mount Fuji, for example.)

The negotiators are supposed to get to agreement on the Treaty by the end of this year, and the third of five rounds of negotiations was held in Nairobi in November, to discuss what’s known as the ‘Zero Draft’, an early version of the treaty. Li Jiacheng, who wrote the China Dialogue article, was an observer at those talks.

The TL:DR version of the article:

Much remains to be done in order to achieve an international, legally binding plastics treaty. These actions include reaching a global consensus on the definition of “plastic pollution”, which is far from being achieved due to countries’ differing interests in plastic, as well as an agreement on how voting should work on substantive issues within the negotiations.

Reading this account, it’s clear that the same conflicts that bedevil every other attempt to reduce environmental impact on the planet are being played out here as well.

(Image: rawpixel. CC0)

One of the critical issues for the treaty is how it deals with “virgin plastic polymers”. Despite the name, these are new plastics created by the oil industry. They are

newly manufactured resin produced from petrochemical or biomass feedstock used as the raw material for the manufacture of plastic products and which has never been used or processed before.

A short Environmental Investigation Agency briefing reportsuggests that this production of ‘virgin plastic’ has reached “unsustainable levels”:

Countries are inundated by an acute overabundance of inexpensive virgin plastic, undermining secondary markets for recycled material and investments in collection and recycling infrastructure. This has been partly driven by the oil and gas industry turning to plastics to hedge against the possibility that a serious climate change response will reduce demand for their products.

So guess what: countries with fossil fuel interests—Russia, Saudi Arabia, and others—are hard at work trying to undermine the sections of the treaty that address this over-supply of virgin plastic:

14 oil-producing nations spoke against the proposal in the Zero Draft on virgin plastic polymers. The proposal offered three options for such polymers, with varying degrees of restriction, and the oil-producing nations objected on the grounds that it exceeded the mandate of the UN Environment Assembly Resolution.

The Chinese delegate suggested that plastic polymers should be removed completely from the treaty.

And, of course, the place was crawling with fossil fuel lobbyists. According to the US Center for International Environmental Law:

Over 143 lobbyists from the petrochemical industry attended the meeting, a 36% increase on the previous one in Paris. Not only concerned with the upstream, petrochemical lobbyists, including ExxonMobil, also wanted a piece of the downstream pie.

Another issue that seems familiar from other international environmental negotiations is, in effect, the problem of waste, including plastics, that gets shipped from the richer world to elsewhere. China banned these shipments in 2018, following an international agreement on global rules on cross-border shipments of plastic waste. The result seems to have been that more ends up in other parts of the world, Asia included.

It’s worth going back to a Yale 360 report looking at plastic waste in Indonesia that I didn’t get around to writing up in the second half of last year:

some countries on the receiving end of the developed world’s waste exports are acting on their own. Indonesia, like its neighbors Thailand and Malaysia, was hit by a tidal wave of foreign trash after China — long the top destination for rich nations’ discarded plastic — stopped accepting it, and exporters in North America, Europe, Australia, Japan, and South Korea scrambled to dispose of mountains of waste that quickly accumulated.

Staying with the Yale 360 report, Indonesia responded by tightening its own rules, and formally, at least, only accepts well-sorted plastics waste, there are still vast plastic dumps outside the cities:

While Indonesia has begun to get a grip on its imports, the scrap trade’s opaque global web is an ever-shifting cat-and-mouse game. When one country erects barriers, those with material to get rid of often just find someplace else to send it. The U.S., for example, ships less plastic waste to Southeast Asia than it did even a year ago, but it sends more to Mexico and India. European nations that previously shipped to Thailand now favor Turkey, data show .

This spilled out into the Nairobi meeting, at least in some of the side meetings.

Pui Yi Wong, an observer delegate from Malaysia.. asked how China had cleaned up the plastic that had leaked into the environment as a result of imports before the ban, which had entered into force by the end of 2017. Regrettably, this question was not directly answered.

By the end of the Nairobi meeting, the 31 page Zero Draft had grown to 70 pages, and had attracted more than 2,000 comments, almost a third of them “in opposition.” The fourth round of negotiations is taking place in Ottawa in April, but the proposal to do interim work before then was not adopted, and many of the procedural issues had been put into the too hard tray. It might be tough going in Canada.

Yes the planet got destroyed. But for a beautiful moment in time we created a lot of value for shareholders.

j2t#538

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Thanks!

"What happened around 2010 that caused these similar effects in US, Germany, and the UK?"

"2010" as a specific year is probably not useful to look at since this is a structural change in political culture. Following the introduction of the first smartphones in 2007-2008, when 4G rolled out in 2009 it created the field for the always-online lives that we now take for granted. While there were many other factors involved, this one seems to be the most obvious - complete transformation of the mass communication which is the prerequisite for political formation.