3 November 2023. Jobs | Migration

Britain’s ‘bad jobs’ problem. // ‘Those who move freely and those who are forced to move’ [#510]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: Britain’s ‘bad jobs’ problem

One of the best books on labour markets is The Case for Good Jobs, by the Turkish American-based academic Zeynep Ton. Off the back of that book she created the Good Jobs Institute, which consults with businesses which want to create good jobs. I was reminded of this book by a few things.

The first was a recent review of the 2014 book by Joost Minnaar at Corporate Rebels. The second was an FT article by the paper’s data journalist John Burn-Murdoch on how Britain’s graduates were suffering because the UK economy wasn’t producing enough decent jobs. And the third was a piece by Jonn Elledge in his newsletter about the relationship between the quality of jobs and productivity.

So let me thread my way through the connections here.

Because Zeynep Ton’s work isn’t just about the benefit of good jobs. It’s also about the problems caused by bad jobs. Minaar’s review focusses on the bad jobs first:

Ton argues that most traditional companies have a pay issue. That is, they underpay their people. Most notably, they underpay their frontline people... So, most people are neglecting the people who have the most significant influence on their customers. And that's a big mistake. Ton calls jobs that are underpaid "bad jobs." They are called that because they launch the companies (that underpay their people) into a vicious cycle of bad performance.

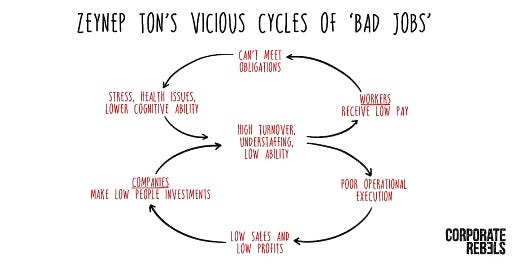

She describes two interlocking cycles of decline created by bad jobs, starting from high turnover of staff, understaffing, and low ability. The Corporate Rebels guys have turned this into one of their distinctive graphics.

(Image: Corporate Rebels, based on the work of Zeynep Ton.)

If you’re used to looking at diagrams like this as the two halves of a causal loop diagram, one balancing, one reinforcing, you’ll be confused by this. But the point is that both these loops are spirals of decline.

To the top, low pay leads to workers who can’t afford to live, which leads to stress and health issues. To the bottom, poor quality staff lead to poor execution, which reduces sales and profits (and increases costs), which means that the company can’t invest in people. And off it goes again.

Good jobs do pay better than bad jobs. But that’s not enough. We know that pay is just a hygiene factor. So to create good jobs, you need to invest in people.

Minaar summarises the four characteristics of this process, and I’ll catch the headlines here:

Focus and simplify: “Good companies” (with good jobs) have a strong focus on those things that add value to the customer. They maintain discipline in keeping things simple.

Standardize and empower: Good companies let go of command and control. Instead, they leverage front-line workers' knowledge, time, and ability.

Cross-train: Good companies design the work so employees can balance specialization, flexibility, and motivation...

Operate with slack: Good companies ensure their employees have enough time to serve customers and do their work without mistakes. Moreover, they do not force staff to work at full capacity, so they also have time to focus on improvement and innovation.

In the book Ton acknowledges that none of this is new. But it seems new because of the way that companies declared war on labour from the 1980s onwards. The book has a number of examples, including the Spanish supermarket chain Mercadona, which effectively used a good jobs strategy to compete from a position of market weakness.1

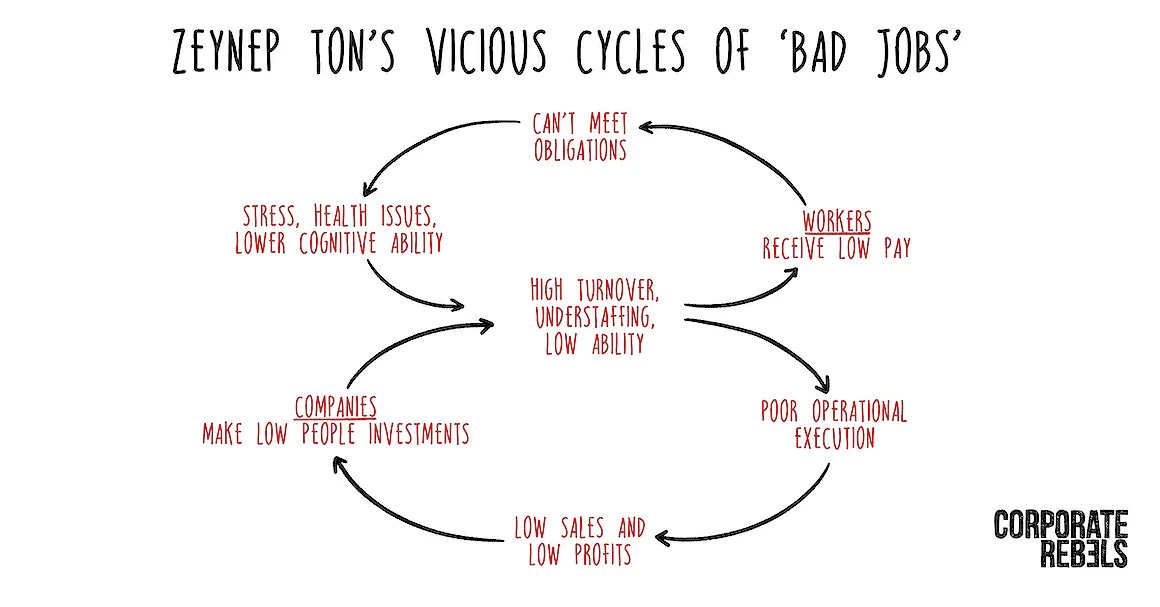

(Source: John Burn-Murdoch, Financial Times)

This is related to John Burn-Murdoch’s investigation into why, in Britain’s labour market, the graduate premium has been shrinking whereas this is not true in other labour markets. The chart shows that all levels of educational attainment, short of a university degree, earnings in the two countries are similar, adjusted for inflation and price levels. But graduate pay in the UK has been sliding.

On the eve of the global financial crisis 15 years ago, British graduates made just 8 per cent less than US grads; that gap has ballooned to 27 per cent. These are essentially the same people. Same age, similar educational milestones achieved, increasingly inhabiting the same culture as the internet and social media blur national boundaries. Yet one group is paid 40 per cent more. What can explain such a dramatic divergence?

It’s not to do with choice of degree, which is broadly similar. It’s down to the British economy not producing enough skilled jobs. The only place where the graduate premium has been maintained is in London.

The UK’s skilled workforce is clearly underutilised, but America’s far better results with a similarly sized and skilled labour pool suggest Britain is burdened with weak demand for valuable skills, not oversupply of skills. The correction needs to be through the supply of suitable jobs.

In short, the whole of the British economy has a bad jobs problem. The two cycles of decline in the Corporate Rebels diagram have been caused by years of under-investment, exacerbated by austerity and Brexit.

In his newsletter, Jonn Elledge ventured into this space, perhaps slightly inexpertly, since he was making a point that left-leaning economists have been making for a few years now. But the point is still important. And the point is that productivity follows higher wages and good jobs, because higher wages encourage employers to invest.

This is for two reasons. First, because getting workers to do the things they do best is more important when wages are higher. (Aditya Chakrabortty made a similar point in a Guardian article a few years ago when he observed that the rise of “car wash by hand” places was a function of a low wage, low investment economy).

The second is that higher wages get spent, and therefore increases demand, so companies can afford to invest.

As Elledge put it:

The argument against wage rises has always been that they aren’t affordable unless productivity is increasing. But – call me a Keynsian – I’ve begun to suspect the causality here is the wrong way around. What if employers haven’t needed to increase productivity because wages aren’t rising? If the wage bill was going up, after all, employers would have to invest in training and equipment to make sure its staff were earning their keep.

He also makes a direct link between the government’s policy of austerity and low wages for graduates. The public sector, directly and indirectly, was a heavy employer of graduates, at reasonable wages. One good sector keeps the rest of the labour market honest. Fixing this, argues John Burn-Murdoch, will require taking the economic challenge of “levelling up” seriously. Because we need this investment to happen outside of London.

2: ‘Those who move freely and those who are forced to move’

I was in Istanbul last week to facilitate a workshop on migration and mobility for the International Organisation of Migration. I can’t say much about the workshop yet, but there will be a report out in the new year.

As I was preparing for the workshop I looked around for pieces that would stretch my thinking, and one of these was by a Bosnian-Australian writer, Dženana Vucic, on returning to Bosnia from Australia and finding that she didn’t fit in there. She now lives in Berlin, after a period of time in Glasgow. Her piece was published in the Sydney Review of Books, and I don’t have space to do it complete justice here.

(Migrating birds. Via Pixahive, CC0)

Her mother had left Bosnia during the Balkan war, and she had been back once before, while still a child: Bosnia is a long way from Australia, and the flights are expensive:

When I went back to Bosnia a second time, as an adult and alone, I stayed for three weeks. It wasn’t enough so I returned for six months, intending it to be forever. This is the kind of decision you can make at twenty-five. Impulsive, reckless... I wanted to know where I had come from, and whom. In Bosnia, I learned to speak my mother tongue, albeit haltingly; to drink coffee short and strong and sweet; to cook grah with Vegemite in place of suho meso. I learned, too, that I had been gone too long, that I could not stay.

Much of the village where she was a child was destroyed by the war, and the nearby village where her mother was born. Young people have left in search of work, leaving the old to grow food in the fields. (This is also a reminder that most migration doesn’t cross borders.)

Bosnia has high unemployment, and Vucic’s extended family, cousins with “useful degrees” from “respected Bosnian universities” mostly have to settle for the work they can get. Even staying in Bosnia they end up servicing the economies of high income countries:

they take jobs doing whatever they can: operating heavy machinery; cooking meat in a ćevabdžinca; waiting tables at the local hotel; telemarketing dodgy investments to rich Americans; online customer service for German multinational white goods companies; assembly-line work in the munitions factory next to Tito’s bunker.

She realises she can’t stay there, because, as she puts it, “I was – am – too much the hyphen”. But she wanted to stay close enough to visit every year, which ruled out a return to Australia. After a while she settles in Berlin:

My relationship to Berlin is one of necessity and convenience. Islamophobia curls through conversations – even on the left, sometimes especially on the left – and my name makes bureaucrats grit their teeth. Eastern Europe is not Europe and Muslims are not Europeans. A certain kind of German wants us Kanaken to remember that.

Being Bosnian in Germany is not unusual. There have been Bosnian gastarbeiter in Germany since the end of world war two. These days, German employers, such as Munich airport, still come to Bosnia to look for workers:

(W)omen for customer service jobs for which they would need a modicum of English; men for jobs in luggage handling and waste disposal for which they would need only their desperation. Visas are not offered with these jobs; if they were, the workers would need to be paid a liveable minimum. But without work, there is hardly any hope for a visa except through marriage or the visa lottery.

Her cousin’s fiancé, with a degree in traffic engineering, gets a job operating machinery in a factory near Ulm. But her cousin could not get a job there because, he was told, they did not hire women.

One of the other things I read before the workshop was John Berger’s 1975 book A Seventh Man, made with the photographer Jean Mohr. It is about the experience of migrant male workers in Switzerland, and they, too were there on sufferance to do the dirty work, in this case building a tunnel underneath Geneva:

The workers, except for a specialist mechanic and electrician, are on nine-month contracts. When the contract finishes they return to their Bosnian or Andalusian or Calabrian villages and then re-apply for another year's chance of tunnelling under the international metropolis. According to Swiss law the residence-permits (Type A) of these workers do not permit them to stay longer than 9 months (although they may continue to come year after year) nor to bring with them any of their family.

In her article, Vucic quotes the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, who said that there were two classes of people in the world:

those who move freely and those who are forced to move – by war, climate change, lack of resources. ‘Tourists’ and ‘vagabonds’ he called them. With an Australian passport I am the former, slipping past borders with shameful ease. Certainly, in Germany, passport control officers still linger on my documents, still bark rhetorical questions (You travel a lot, no?! You’re in Bosnia a lot, I see! Your visa will expire in October, okay?!) while flicking through my passport page by page.

Reading her article made me wonder about the way in which politicians—usually conservative ones—are dismissive of people who they label as ‘economic migrants’, as if travelling to find work was somehow a bad thing, or a new thing.

But one of the dirty if obvious secrets of migration and mobility is that the rich, and people with power in the labour market, get to move more or less unencumbered—and are rarely called migrants—but people without that power get short contracts and no visas. There are evident dimensions of class, nationality, and ethnicity here.

3.6% of the world’s population live outside of the country they was born in, but five per cent of the world’s labour force, or 169 million people, is made up of migrants, according to the ILO. 99 million of these are men, and 70 million are women. They work in service industries, or in agriculture, or in industry:

Their ‘host’ will most likely be a high-income or upper-middle income country, and they will make up almost twenty per cent of that country’s workforce ... For many Gastarbeiter, to live in the West is not cheap. Even so, migrant workers typically send money home or save it to spend at home, often living in cramped, dormitory-like shareflats, subsisting off rice and bread with pavlaka.

The ‘tourists’, meanwhile, from the high income countries, are increasingly offered the chance to live and work in poorer countries with better weather where the cost of living is lower. Portugal now allows non-European citizens to live and work in the country for up to five years provided they earn €2,800 per month, or four times the country’s minimum wage. In Latin America, too, countries are trying to attract workers—‘digital nomads—from North America who are now able to work remotely. They live in nice parts of the city and price out the locals.

j2t#510

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

My former colleagues at the commercial consultancy used to joke that after I read The Good Jobs Strategy they could tell one of my presentations because I’d always work in a reference somewhere to Mercadona.