3 May 2024. Climate, again | Murals

The problem with politicians and climate change // Bringing the city walls to life [#567]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: The problem with the politics of climate change

I wrote something here earlier this week about the so-called climate ‘backlash’, and some actual evidence on this. To summarise the research, from the Jacques Delors Institute, they found from surveying 15,000 people across France, Germany and Poland, that

In Germany and Poland, 60% said they were already affected by climate change, or expected to be in the next five to ten years. In France this was 80%

A majority in all three countries wanted their governments to do more in response to climate change

Although there is a minority in all three countries who are delayers or deniers, this number had not increased in recent years.

Which raised the question for me of why progressive and centrist politicians kept appeasing the delayers, when doing so was not in their political interests. I had a couple of theories about this:

The first was that particular corporate interests choose to amp up the noise of climate delay, and they have good access to politicians

The second was that appeasement reduced the trust levels of progressive and centrist voters, and they stop believing that their interests are going to represented in the political system.

I had another thought at first, which I discarded: that it is always easier to aggressively oppose something than advocate for it. The delayers, on this reading, want it more. This is a staple of political science. I discarded it because it is not true; the advocates of action on climate change have wanted it a lot, and have been quite aggressive.

But they have been largely silenced by the law and the courts, in Britain and elsewhere. They have criminalised pro-climate activism, and silenced pro-climate voices, treating it as a policing and legal problem, while treating anti-environmental protests as a political problem. This has shifted the political centre of gravity away from pro-climate action.

Anyway, this prompted a lively email discussion with Ian Christie, and I’ll try to reflect that here. Any errors are mine, of course. It

One of the starting points in this was that pro-climate discourse is also damped down because people have a belief that others care less about climate change than they do. This finding was reported by Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data, and seems to be a worldwide phenomenon.

She draws on a 2024 paper by Peter Andre in Nature Climate Changethat drew on 130,000 respondents in 125 countries worldwide. The research

It asked people if they’d be willing to give 1% of their income to tackle climate change. Across the 125-country sample, 69% said “yes”. They then asked the same participants what share of others in their country would say “yes” to the same question. The average across countries was just 43%. This wasn’t just the case in some countries; it was the case in every country.

(By the way, I suspect that this doesn’t tell us that that many people would actually give 1% of their income to tackle climate change. I think it’s just a clever research device). Anyway, the data looks like this:

(Source: Our World in Data)

In short, if people thought other people would be exactly as willing to give 1% of their income as they were, the dots would follow the dotted line exactly, rather than being below it.

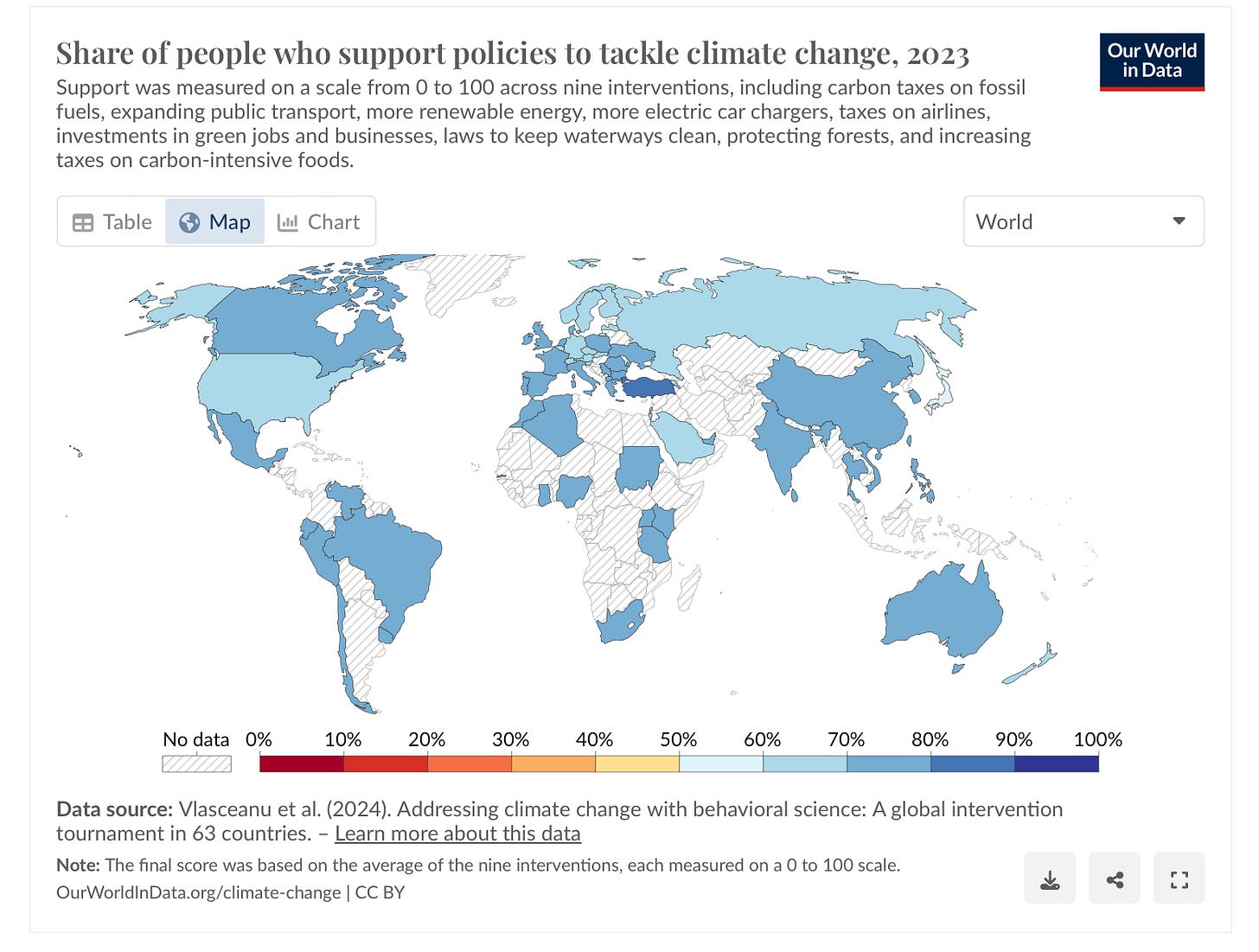

Ritchie also quoted 2024 research by Vlasceanu et al that a global majority supported action to tackle climate change—an average of 72% worldwide. So this is consistent with the Jacques Delors Centre research, although the methodology is a bit different—they tested specific climate responses.

(Source: Our World in Data)

So the first thought here is that support for climate change policies is consistently underestimated, and not just by politicians. But politicians are quite likely to reflect the same perceptual biases as other citizens.

But in our discussion, Ian and I didn’t think this was the main reason why politicians find it hard to advocate for climate change.

This seems more likely to be an issue of the timing of professional formation. Most politicians get trapped in the worldviews that dominated when they arrived in politics, and most of our current political leaders have been conditioned by their arrival in politics in the heyday, pre-financial crisis, of neoliberalism. (Obviously this will change over time, but it will likely take another decade or so).

So they have been conditioned to believe that business leaders are interested in deregulation, privatisation, and markets, rather than industrial strategy. This is despite the fact that actually existing business leaders repeat ton them over and over again that they are in favour of consistent, long-run, and well-regulated approaches to climate action.

There are some leading politicians who are exceptions to this. Ian mentioned the example of the Green vice-chancellor of Germany, Robert Habeck, who has good communications skills and has tried to face down resistance to pro-climate policies. But he doesn’t get support from his partners in the German Coalition, who prefer to shy in the face of any delaying or denying noise.

There is also something relentlessly short-termist about all of this. The French Government has been surprised by anti-environmental protests so often now that it shouldn’t be a surprise to it. You would have expected that the EU’s futures capability (which isn’t trivial) to have red-teamed some of the climate delay policies.

But no.

At the moment I’m reading Dan Davies’ book The Unaccountability Machine, in which he sets out to rehabilitate Stafford Beer’s management cybernetics. I wrote about part of this recently, and I’ll come back to it again here when I have finished it. But for the moment, without going too deep into it today Beer argued that viable systems have five systems, all of which are necessary.

System 4 can be described as “intelligence”, which looks outside of the organisation at its wider environment and also tries to anticipate change in that environment. System 5 is translated by Davies from Beer’s more technical language as “purpose and identity”.

Together these two systems are necessary to enable any kind of long term thinking and strategy, and any kind of adaptive strategy.

One of the things that the climate discussion makes clear is that the System 4 and System 5 in most contemporary politics are deformed or underdeveloped. The political crisis about climate change—which is, of course, making the climate crisis worse—is a function of this wider failure.

2: Bringing the city walls to life

I haven’t done a visual essay here recently, but a thread on ex-Twitter by James Lucas provides an excellent reason to do one. He looks at the power of murals to transform dead urban space into something that seems to come alive.

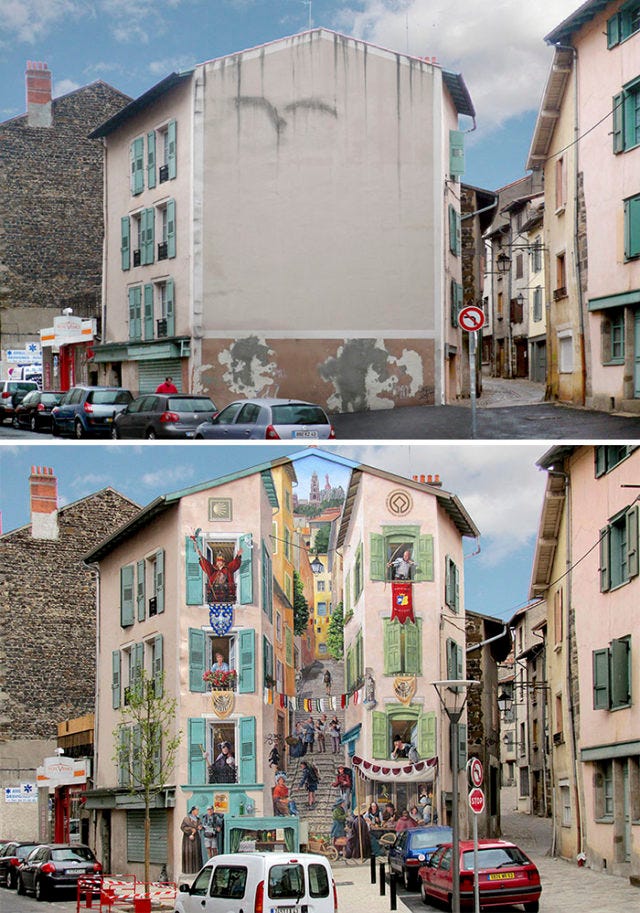

The first example here is by the French mural artist Patrick Commecy.

Before above, after below:

(Patrick Commecy)

Commecy is quoted as talking about the mural as a form of public art:

"When you paint a wall, you are creating something for the public. Anyone can see it: young, old, rich, poor, people of all creeds, nationalities and political views."

The Brazilian artist Fábio Gomes Trindade uses plants and bushes to bring his murals to life. (Detail in the top part of the picture).

(Fábio Gomes Trindade)

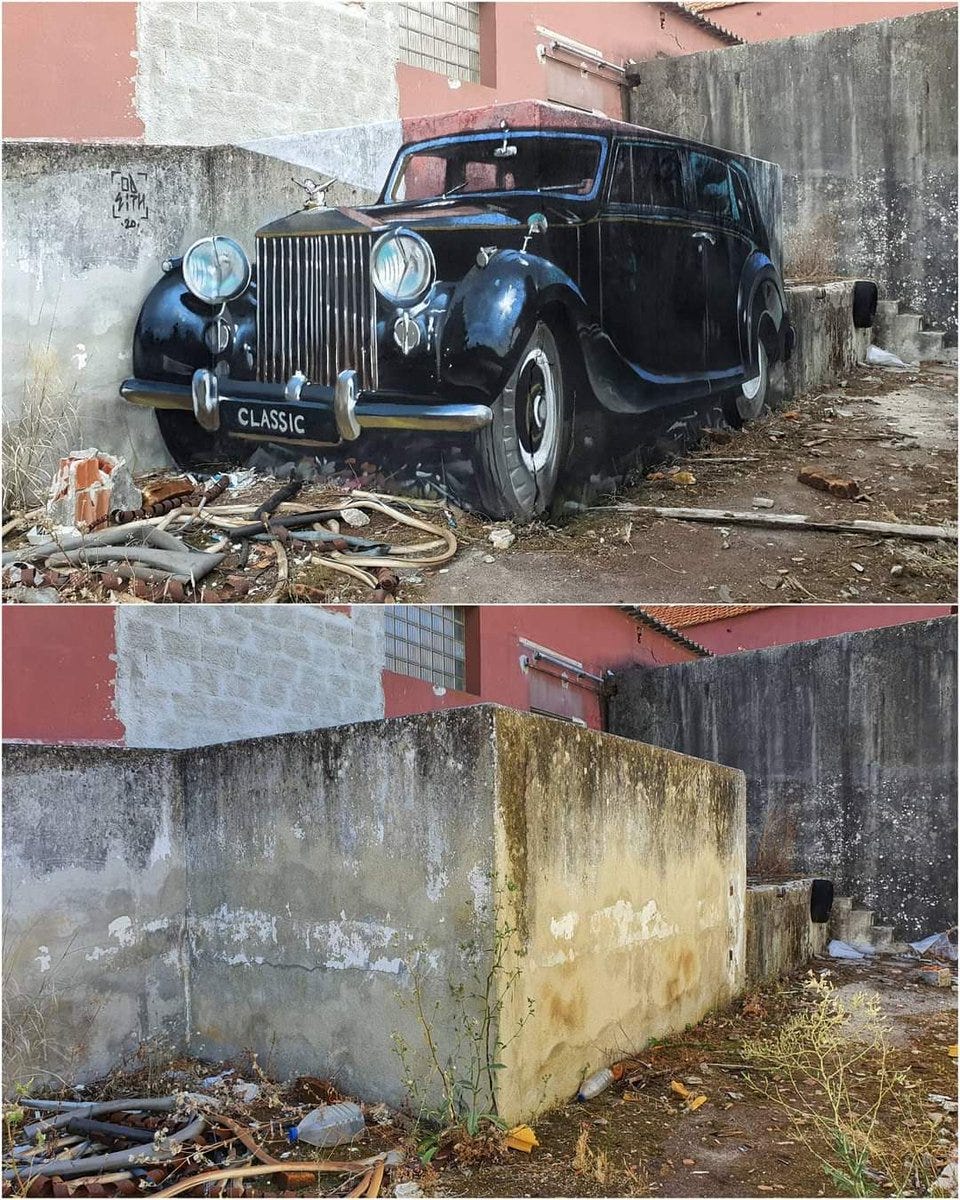

The Portuguese graffitti artist Sergio Odeith also uses location apparently to bring things to life. The three dimensional effect here is based on the shape of the walls he is working with.

(Sergio Odeith)

Kevin Lee used a flight of steps to create this mural, known as ‘The Invisibility of Poverty’.

(Kevin Lee)

I’ve only picked up a few of his examples here, but some of the ones he showcases work because of their sheer scale. Jorit’s Maradona, in Naples, for example.

(Jorit)

And there’s something transcendent about this Glasgow mural, called St Mungo, which also benefits from scale. It’s by ‘Smug’.

(Smug)

You don’t necessarily need walls. Lucas showcases the ephemeral pavement work of David Zinn, who works in chalk and whose pieces are washed away by the next rain. It took me a couple of looks to realise what he’d done here in incorporating the rock into the picture.

(David Zinn)

I have a small amount of skin in this particular game. About 40 years ago I bought a house in Brixton, in south west London, on the end of a terrace that had a huge gable end. The main visual features were occasional bursts of racist graffiti, that the council would come round and clean from time to time.

The neighbourhood association asked me if I’d be willing to have a mural painted on there—they had asked the previous owner, who had turned them down flat.

The artist who was commissioned to do the work turned it into a rural scene, called ‘Big Splash’. The local kids (at the time) played around the pool; our car nudges out through a trompe l’oeil window. It’s still there—and has even made the pages of Wikipedia.

('Big Splash’, on Glenelg Road (London SW2) by Christine Thomas, assisted by Dave Bangs and Diana Leary. Photo: LeticiaGolubov (2010), CC BY-SA 3.0)

j2t#567

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.