1 May 2024. May Day | Climate politics

The Red May Day and the Green May Day // What ‘backlash’? European voters are in favour of climate action [#566]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The Red May Day and the Green May Day

As May Day approached this year I finally got round to a small project I’d been meaning to do for a few years now. This was to read Peter Linebaugh’s book The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day, which is a collection of pieces he has written over the years—some pamphlets, some articles—for and about May Day.

Peter Linebaugh is a radical American historian, probably best known for his books on English history—on 18th century capital punishment in The London Hanged, on the history of the commons in The Magna Carta Manifesto. He’s clear which side he’s on.

We usually associate May Day with the history of the labour movement, and there are good reasons for this, which I’ll come back to. Linebaugh calls this ‘Red May Day’. But he argues that the history of this version of May Day is completely intertwined with a much older and longer tradition which we see across much of Europe. In Celtic culture, this festival is known as Beltane, and it sits about half way between the spring equinox and the longest day of the year. This is ‘Green May Day’.

He connects this part of the history of May Day with what he calls the “Woodland Epoch of History”, when the huge forests across Europe, Asia and Africa provided our ancestors with the resources they needed to live:

In Europe, as in Africa, people honored the woods in many ways. With the leafing of the trees in spring, people celebrated "the fructifying spirit of vegetation," to use the phrase of J.G. Frazer, the anthropologist. They did this in May, a month named after Maia, the mother of all the gods according to the ancient Greeks, giving birth even to Zeus.

Different cultures celebrated this in different ways. The Greeks had sacred groves, the Romans had games, the Celts and the Scandinavians lit fires:

Everywhere people "went a-Maying" by going into the woods and bringing back leaf, bough, and blossom to decorate their persons, homes, and loved ones with green garlands. Outside theatre was performed with characters like “Jack-in-the-Green" and the "Queen of the May." Trees were planted. Maypoles were erected. Dances were danced. Music was played. Drinks were drunk, and love was made. Winter was over, spring had sprung.

(These quotes, by the way, come from the title essay of the book, originally written in 1986 and printed as a pamphlet with alternate red and green covers. It’s the single best in the book.)

The Red and Green May Days can be described in ways that create the kinds of opposites that narratologists get excited by:

Green is a relationship to the earth and what grows there-from. Red is a relationship to other people and the blood spilt there among. Green designates life with only necessary labor; Red designates death with surplus labor. Green is natural appropriation; Red is social expropriation. Green is husbandry and nurturance; Red is proletarianization and prostitution. Green is useful activity; Red is useless toil. Green is creation of desire; Red is class struggle. May Day is both.

The Red May Day has its roots, in particular, in the bloody history of the American labour movement, and in particular in the city of Chicago, which in the late 19th century was an epicentre of both industrialisation and globalisation.

The story of the Haymarket riots is told in different ways in most of the pieces in the book. It has May Day at its heart. On May Day 1867, the machinists who made reaping machines for McCormick went on strike for an eight-hour day. McCormick was a huge agricultural machinery business by the standards of the time. The workers didn’t make much progress with this, but over the next twenty years Chicago became known for its waves of strikes and the repressive violence that met them.

In 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades Unions of the United States and Canada declared 1st May 1886 as the date which would mark the start of the eight-hour working day. Throughout the spring of 1886 there was agitation throughout the US for shorter hours. An organisation called the Knights of Labour composed a song for the movement:

We want to feel the sunshine

We want to smell the flowers

We’re sure that God has willed it

And we mean to have eight hours.

And on 1st May, a “storm of strikes swept Chicago”, and four machinists who had been locked out by McCormick were shot dead by police. On 4th May, the strikes continued, and thousands of people gathered in Haymarket Square in Chicago to hear speeches from organisers. During the evening—this part might sound familiar—the police charged the crowd, a home-made bomb was thrown, and in the ensuing violence, many were killed, including seven policemen.

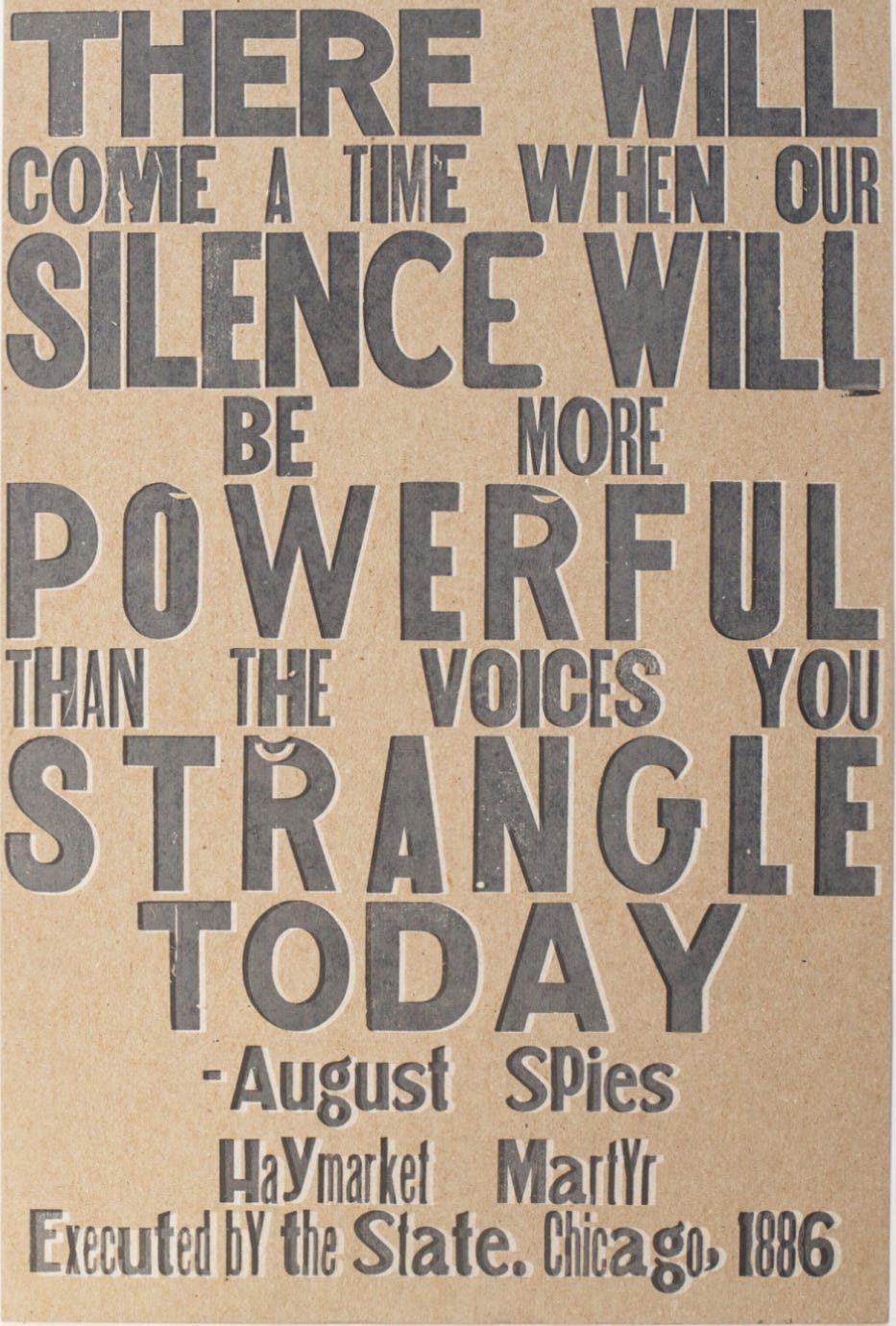

Hundreds were rounded up, and eventually eight radical leaders were charged with conspiracy. Nothing linked the defendants to the bomb, but after a show trial, four of them were hanged.

(The last words of the hanged socialist editor, August Spies. Image: Entangled Roots Press.)

Lucy Parsons, the widow of one of the hanged men, set out to tell the world about this miscarriage of justice. In England she encouraged workers to make May Day a holiday dedicated to a shorter working week; her friend William Morris wrote a poem in her support, in which the Earth talks to the workers. The American Federation of Labour declared it a holiday, and the American union leader Sam Gompers sent someone to Europe to have European trades unions declare it International Labour Day.

By then the idea had caught on: the 1905 Russian revolution started on 1st May. This history runs on through the 20th century. In Mexico, Linebaugh says, May Day is still called “the day of the Chicago Martyrs”. This all spooked American capital enough to declare May Day un-American and move American Labour Day to the autumn.

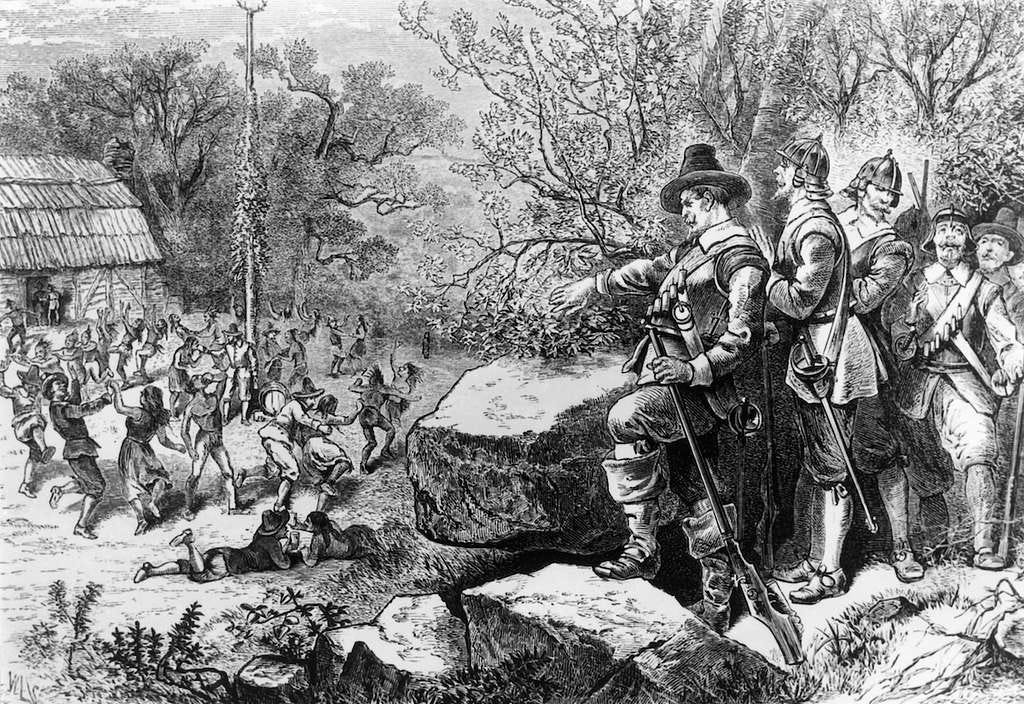

But if this is Red May Day, this violence started much earlier in American history, in suppressing a Green May Day on ‘Merry Mount’ (or Merrymount), as the English migrant Thomas Morton called it, at what is now Quincy, Massachusetts. This history I didn’t know. Thomas Morton had arrived from England in 1625, and found Mount Merry ‘Paradise’. He settled among the native Americans:

Thomas Morton was a thorn in the side of the Boston and Plymouth Puritans, because he had an alternate vision of Massachusetts. He was impressed by its fertility; they by its scarcity. He befriended the Indians; they shuddered at the thought. He was egalitarian; they proclaimed themselves the "Elect." He freed servants; they lived off them. He armed the Indians; they used arms against Indians.

On May Day 1627, he and the local native Americans erected an eighty-foot Maypole, and garlanded it. Songs were sung, and beer was brewed. Verses were nailed to the Maypole:

With the proclamation that the first of May

At Merry Mount shall be kept holly day.

(Captain Miles Standish and his men observe the 'immoral' behavior of the Maypole festivities of 1628 at Merrymount. 1850 engraving, public domain, via Wikipedia.)

As Linebaugh says, Merry Mount became a refuge for runaway servants and the discontented of all kinds. The Governor of Massachusetts called them “all the scume of the countrie.” Morton was told that he was violating the King’s Proclamation, and replied that it was “no law”. The settlement was attacked and burnt down by the Massachusetts Puritans, and Morton was sent back to England as a prisoner, although the Puritans complained about the cost of this.

In the face of this history, it’s hard to be optimistic. Linebaugh sees the struggle over May Day as a fight about establishing the discipline of work. The Puritans were the vanguard of this, “with their belief that toil was godly and less toil wicked”. Isaac Newton bought London’s 100-foot may pole and used it to prop up his telescope, in one of those details that screams metaphor.

All the same, his near 40-year old idea of the Green and Red May Day, with the values they wrap themselves around, seem suddenly to combine themselves into a necessary programme for our times. Our current forms of work, and the double exploitation they involve of planet and people, are at the heart of the climate crisis: ecological justice also requires social and economic justice.

2: What ‘backlash’? European voters are in favour of climate action

One of the current features of the political discourse about environmentalism is that there is a ‘backlash’. Politicians who should know better are running for cover in parts of Europe as farmers protest noisily and effectively about environmental issues.

Even the shrewd Chris Stark, the outgoing Chief Executive of the UK’s Climate Change Committee, muses that ‘net zero’ doesn’t need to be a totem. (I think he’s fundamentally wrong about this, but I’ll come back to this later.)

Fortunately, in the face of this noise, some people are still doing actual research. At Social Europe, Jannik Jensen has summarised a longer report published by the Jacques Delors Centre that he’s been involved in writing. (The data is also available).

The protests create the opportunity for far-right or hard-right politicians to portray pro-environmental protests as being “burdensome”, shifting the centre of gravity of the politics about climate change:

This has led to a growing reluctance among liberal and centre-right politicians to endorse Green Deal initiatives, calling instead for a pause on climate legislation in response to what they seem to perceive as a broader shift in public sentiment. In an apparently hurried attempt to quiet the farmers’ blaring horns in the run-up to the elections, the European Commission even proposed to slash environmental standards that determine eligibility for funding under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

In the face of this, thank heavens for some social research. The Jacques Delors Institute surveyed 15,000 citizens in Germany, France and Poland, which is a decent sample size in each of these countries. They found that in all three countries people were significantly concerned about climate change:

In Germany and Poland around 60 per cent of those surveyed said that they were already negatively affected by climate change or expected to be so in the next five to ten years. In France this proportion even reached 80 per cent.

As a result, when asked, people say they want to see more action on climate change, not less, and this view extended well across the political spectrum:

(W)hen questioned on whether existing climate policies were overly ambitious or needed to be intensified, a majority—57 per cent in France, 53 per cent in Germany, and 51 per cent in Poland—favoured more action... advocates of increased climate ambition outnumbering sceptics across almost all political affiliations in the three countries, including among liberal and conservative voters.

There is a substantial minority in all three countries that are sceptical—roughly 30 per cent of the population in Germany and Poland and 23% in France. But there’s no evidence that this proportion has increased in recent years, or that it is caused by economic hardship. Instead it reflected existing political views. The chart shows attitudes to climate change by political affiliation in each country: the more ecological parties are at the top, the harder right parties at the bottom.

(On a scale from 0 to 10, do you think that politics should do more to combat climate change (0) or has it already gone too far (10)?’ (sceptics 5). Source: Jacques Delors Centre.)

Of course, policy still needs to work. The research found that voters had two main priorities. They are in favour of a focus on green investment and pro-climate industrial strategy. These are particularly influential with centrist voters. They are against what the researchers call “broad regulatory measures and price-based instruments”. The researchers suggest that such policies need to be coupled with mechanisms to help the least well-off.

The researchers, therefore, conclude that there’s no benefit in centrist and progressive politicians repeating the narrative about environmental ‘backlash’. Instead:

(P)arties should compete on the best mix of green-investment and just-transition policies to address the EU’s regulatory imbalance. While implementing transition policies will entail significant costs and require political stamina, succumbing to calls for a rollback on climate action would misdiagnose where voters stand on the issue—and ultimately prove more costly.

Some observations from me. The first is that the survey sizes are big enough, and the countries different enough, that we would probably see similar results if we repeated these questions across western Europe.

The second, of course, is that we see these types of results in political research over and over again, across all sorts of subjects. Immigration also comes to mind. There is a hard core of voters, in most countries, that are against modernity, and instead of facing them down, progressive and centrist politicians (whose political interests are generally opposed to this) repeatedly try to accommodate them, and therefore normalise these views.

I struggle with why this is, but I have two hypotheses, which may be related. The first is that corporate interests find it convenient to amp up the rhetoric on issues such as climate change where, frankly, their short-run commercial returns are threatened by policy, and this creates an echo chamber around politics. This has some directly harmful effects. The aggressive criminalisation of climate protest, in many countries, shifts the centre of political gravity towards climate change delayers and deniers.

Related, precisely because of this echo-chamber, it is harder to energise centrist or progressive voters, because they no longer trust politicians to represent their interests properly. This becomes part of a cycle in which democratic politicians fail to understand why voters who would support progressive policies are detached.

And this is why I have doubts about moving away from ‘net zero’ as a target. I’ve been doing some work recently on the connection between visions and goals, and for all of its issues as a measure, net zero is a goal that articulates a vision. (The net zero mobility roadmap report I co-wrote, which illustrates this, is here.)

And the minute you decide to move away from it, we just know how all the bad and bad faith actors will start to redefine our climate targets in such a way that they quickly become meaningless.

j2t#566

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.