3 February 2022. Ulysses | Children

How ‘Ulysses’ contested the future in 1922. The prospects for children in 2022

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

Apologies for the late delivery of Just Two Things yesterday morning: I think it was a Substack glitch, but it might have been user error.

1: How Ulysses contested the future

It was the centenary of the publication of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses yesterday, and there has been some excellent coverage. In this short post, I’m planning to discuss the book and its publication as a ‘futures object’—albeit with the benefit of hindsight. Ulysses is, of course, one of the greatest texts of the Modernist movement.

(First edition of Ulysses. Photo: The Little Museum of Dublin, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0)

At the time, in the 1920s, it was way, way, over the edge. As Rachel Potter notes in The Conversation:

Ulysses, by the standards of the day, was extremely sexually explicit, showing Bloom being fisted in a brothel and his wife Molly musing on the joys of being “fucked” hard by her lover. As well as being a vast collection of literary and religious quotations and everyday trivia, it is also an encyclopaedia of obscene words.

At Memex 1.1, John Naughton, who’s a big Ulysses fan, dipped into Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book, published in 2015. The publishing response to the book, and the legal response and the (divided) literary response, makes it clear that it was a signal from the future.

Sylvia Beach, at the English language bookshop Shakespeare & Company in Paris, decided to publish after everyone else had turned it down (including progressive publishers such as the Wolff’s Hogarth Press). John Naughton:

The book was banned as obscene, officially or unofficially, throughout most of the English-speaking world for over a decade. And the fact that it was forbidden is part of what made the novel so transformative. Ulysses, says Birmingham, “changed not only the course of literature in the century that followed, but the very definition of literature in the eyes of the law”.

In the UK, it wasn’t published until 1936. In the US it was prosecuted before it was published, under a law forbidding the circulation of obscene material in the US Mail:

A portion was burned in Paris while it was still only a manuscript draft, and it was convicted of obscenity in New York before it was even a book (parts of it were published in instalments by a small magazine)... Government officials on both sides of the Atlantic confiscated and burned more than a thousand copies.

According to Wikipedia, the publisher Random House changed the US legal position by importing one of the editions published in France, arranging to have it seized by customs, and then challenging the seizure—successfully—in court.

Of course, Ulysses wasn’t unique in this. Lady Chatterley’s Lover, published privately in 1928, wasn’t published in Britain in an unexpurgated edition until Penguin won its court case in 1960. Lawrence’s The Rainbow was also banned as obscene.

It wasn’t just obscenity. Rachel Potter also points out that Ulysses

was blasphemous, beginning with the character Buck Mulligan mocking the rituals of the Catholic Church.

One of the reasons that first editions of Ulysses are now so expensive is that there aren’t many of them left. The ones that did survive were stored out of the way at Shakespeare & Company:

(A)s one writer remembered, “Ulysses lay stacked like dynamite in a revolutionary cellar.”

The Guardian has republished its review of the book, which dates from March 1922. (The reviewer was a fan).

What, it will be asked, is the good of a book which must be carefully locked up, which only a handful of people will read, and which will be found unspeakably shocking even by that little handful? But one must not talk about the utility, the wisdom, the necessity, of a work of art. It is enough to know that Mr Joyce felt that he had to write Ulysses, and that accordingly, he wrote Ulysses.

Wikipedia also has an intriguing section on the immediate critical and literary response.

On the one hand, T.S. Eliot liked it:

"I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape."

Other reviewers weren’t so keen. The Daily Express thought it contained

“ secret sewers of vice ... canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images, and pornographic words (that) debases and perverts and degrades the noble gift of imagination and wit and lordship of language".

The Quarterly Review called it

"literary Bolshevism ... experimental, anti-conventional, anti-Christian, chaotic, totally unmoral".

These reviews remind me of the response in 1960 to Michael Powell’s experimental, and now revered, horror film Peeping Tom, which well respected film reviewers felt should be flushed ‘swiftly down the nearest sewer’ and never seen again. When reviewers think that something is in the worst possible taste, it’s because a whole set of conventions have been breached.

Joyce was a pacifist, and much of Ulysses was written during World War 1; he was fiercely anti-clerical, and barely visited Ireland after his mid-20s (and not at all after the age of 30). Naughton points us to a piece by Chris Hedges on Joyce’s view of language:

For Joyce the language we use to know ourselves, whether in official pronouncements, mass culture or the press, which he calls “dead noise,” fragments reality into small digestible bits, sound bites highlighting the trivial, the mythic or the extraordinary. This rhetoric and language obfuscate rather than elucidate... In the name of fact and objectivity, it distorts and lies.

Put like that, Ulysses seems impossibly modern.

Because the sorts of signs that indicated that Ulysses was a “novelty”—Jim Dator’s phrase for something new, something that we haven’t seen before—are harder to see, a hundred years later.

Cultural controversies are less likely to be played out in court. In a post-modern world, critics are less influential and also less likely to defend the cultural canon. “Dead noise” has obfuscated almost everything. Our current cultural controversies seem to be more about a contested past than a contested future. Mark Fisher was right about that.

2: The prospects for children in 2022, and beyond

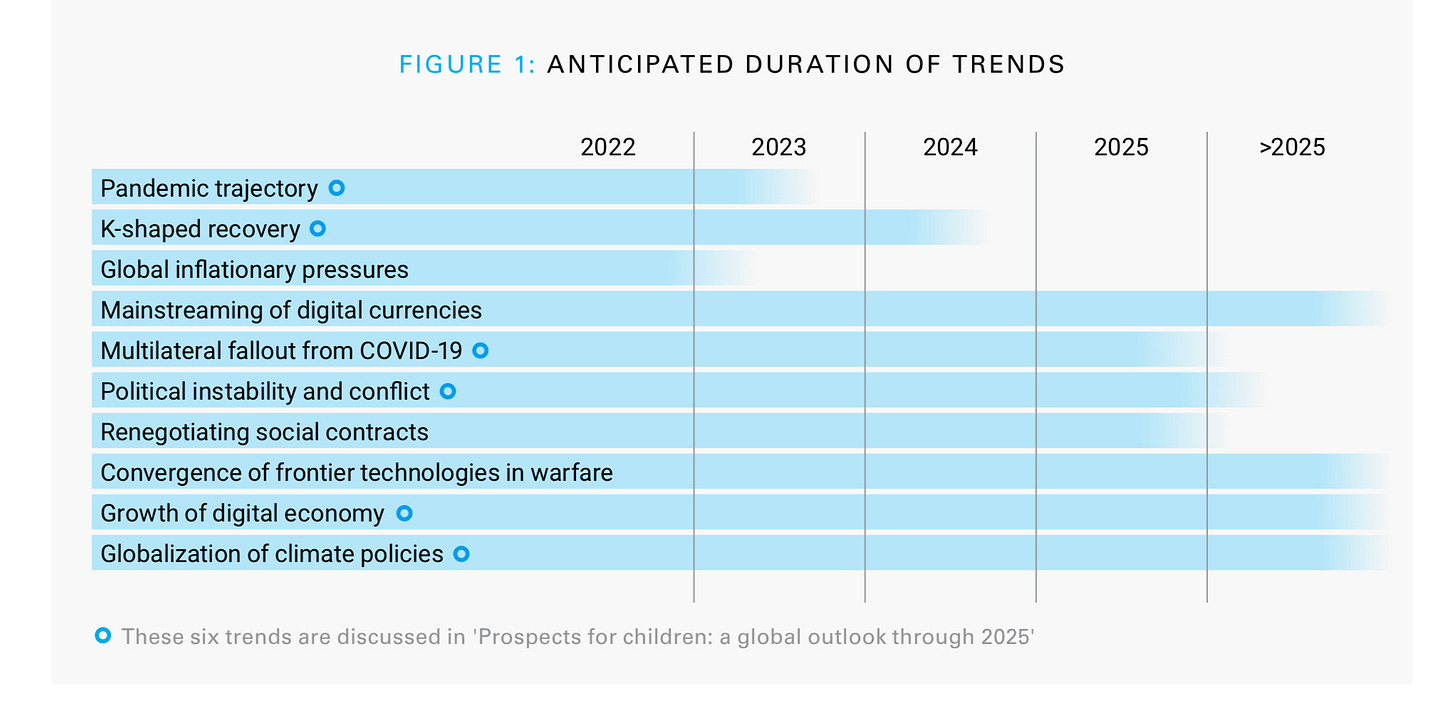

I’m short of time tonight, so this is just a quick note to mention UNICEF’s report on the prospects for children in 2022 and beyond. The report lists 10 big trends that will impact the lives of children worldwide, and comes with a handy little infographic listing the trends and showing how long the impact is likely to last for.

(Source: Unicef)

It’s a smartly design report with interactive links to make navigation easier.

In the short run, they see the pandemic hanging over pretty much everything else when it comes to the prospects for children:

What next for the world’s children in the year ahead? As in the past two years, prospects for children will continue to hinge foremost on the pandemic and how it is managed... Myopic thinking has led to school closures being seen as a largely benign and efficient measure to stem the spread of an infectious disease. yet as we look ahead to 2022 and beyond, the consequences of such steps will increasingly be counted: learning losses that are worse than originally anticipated, school dropouts, negative coping strategies including child labour and child marriage. Without remedial steps, we will continue to count their effects in the years ahead in terms of lost productivity and lower wages.

The report reminds us that we expect 2022 to be a year of record humanitarian needs, with emergencies growing in Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Myanmar. Climate change will not go away, or the extreme weather events that it brings:

As climate change grows in severity each year, it will trigger new disasters, fuel instability, and exacerbate communities’ existing vulnerabilities in health, nutrition, sanitation and their susceptibility to displacement and violence. If the global response to CoVID-19 reveals the ill-health of multilateralism, conflict and climate change serve as a reminder that the deterioration of multilateralism has occurred when it is needed more keenly than ever.

And the effects of technologies are not necessarily benign:

The proliferation of armed drones and their unregulated use is poised to dramatically alter the nature of warfare, while the increased frequency and intensity of cyberattacks pose a threat to various institutions on which children’s livelihoods depend, including schools, other public infrastructure, and banks.

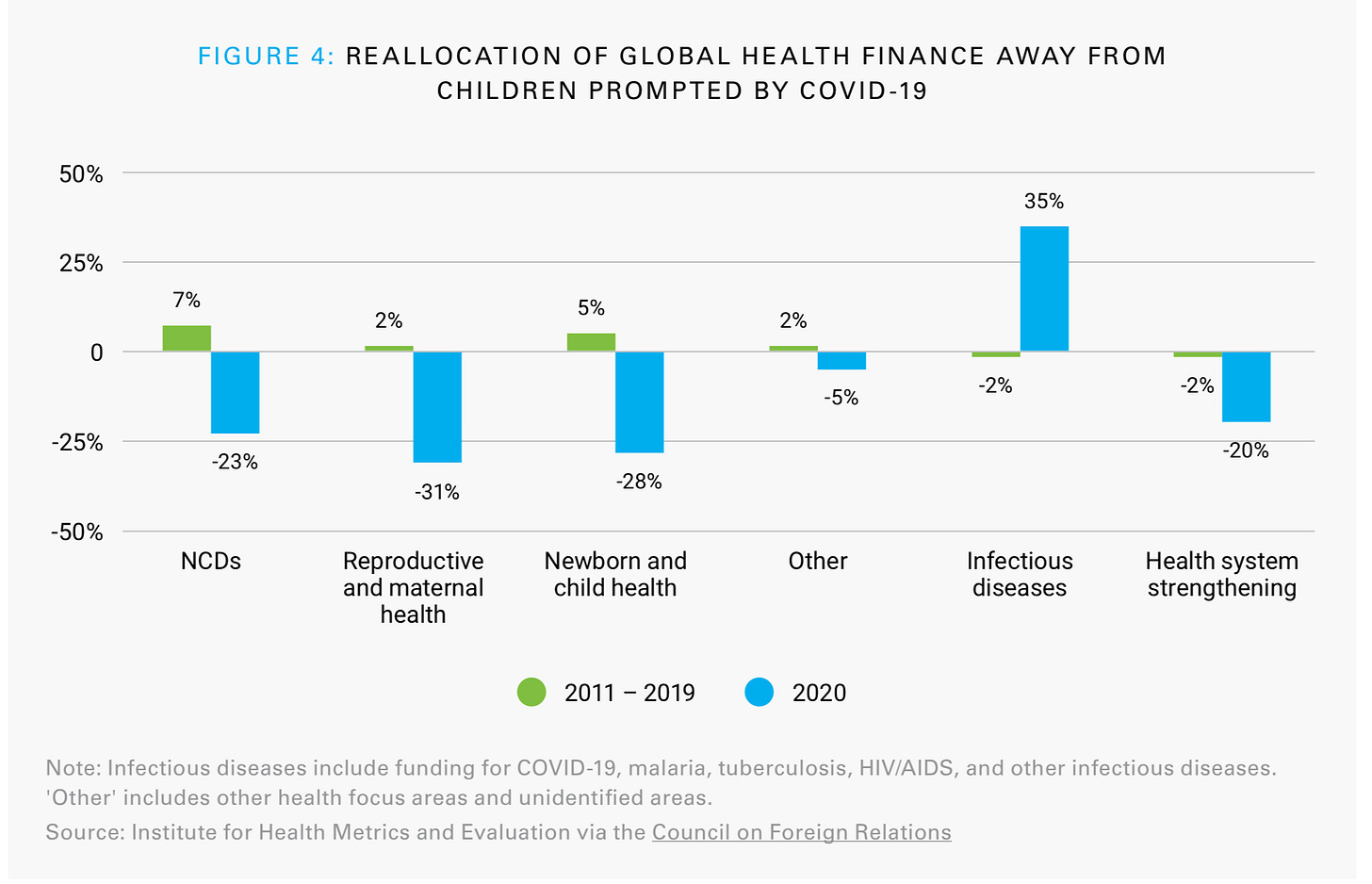

Each of the 10 topics comes with analysis and in some cases useful charts on the impact on children—I was struck by this one on the way in which health resources had been allocated away from children as a result of the pandemic.

(Source: Unicef)

In among this gloom, the tenth trend offers some glimmers that things might get better. It discusses the prospect that “globalization of climate policies, finance and justice movements can spark investments into programmes and sectors that better serve children.”

There’s also a section at the end on tipping points, “black swans” (and how I hate this construction), and “white swans”. The possibility of “military confrontations” between “existing or emerging nuclear powers” is not a black swan. One of the tipping points is also benign: the transition from a fossil-fuel driven transport system to an electric one. Though maybe not in 2022.

Update:

Since I’ve written this week about the efforts of the marketing and advertising industries to address climate change, I should probably mention that there’s a similar initiative from the insight industry. The Insight Climate Collective has just produced ‘Net-Zero In Sight’ (I see what they just did there) which it describes as a “foundational report covering our industry emissions profile, clear steps on how to reduce them and explores other areas where our sector can have most impact.”

j2t#256

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.