29 March 2024. Organisations |

The difference between ‘strong-link’ and ‘weak-link’ problems // Learning from the mistakes of technology reporting [#576]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The difference between ‘strong link’ and ‘weak link’ problems

At his Stumbling and Mumbling blog Chris Dillow makes a distinction that I had not seen before between “strong link” problems and “weak link” problems. It sounds like a bit of jargon, but the difference matters quite a lot to how you might address a question of policy or strategy or business. It’s also a surprisingly rich distinction.

This is how he defines the difference between them:

A weak-link problem is where success depends upon the quality of the worst component, whereas a strong-link problem is where it depends upon the quality of the best.

Chris Dillow likes his football, and he uses the England football team as an example: if you take the “strong link” version of the team, it has a collection of attacking players who are genuinely world class. If you take the “weak link” version it has a creaking defence that makes at least one howler every game.

In football, the distinction isn’t decisive: teams win tournaments sometimes with great attacks and average defences, and sometimes with excellent defences and average attackers.

But if you are running an airline, or an oil exploration company, the distinction ends up framing your whole approach to your business:

If you're running an airline, oil rig or nuclear plant your focus must be on eliminating the weak-links that can cause catastrophes. Other businesses, though, have strong-link problems. It doesn't much matter if there's a lot of rubbish on Netflix as long as there's sufficient good stuff to attract customers. It has the strong-link problem of how to find good shows and can ignore the weak-link one of what to do about rubbish.

(Netflix: a ‘strong-link’ business because people just need to find the good stuff. Photo: Stock Catalog/flickr, ‘Watching Netflix’. CC BY 2.0.)

In the piece, he applies the framework to stages in company growth, to investment models, to economic development, and to political strategies.

In company growth, the early stages of growth are strong-link problems, as you need to stand out from the crowd. But when you are a mature business, it becomes a weak-link problem. You are likely operating in a commoditised market, and your customers can go elsewhere if they want to, so you need to focus instead on the weak link problem of not irritating them with, say, poor customer service, so they go somewhere else.

And managers can fail because they bring a strong link mind set to weak link businesses, and vice versa. Dillow paraphrases Boris Groysberg:

He's shown that when a good manager of growth companies takes over a mature business (or vice versa) the result is often poor performance; a growth manager has a strong-link mindset whereas mature businesses need weak-link thinking. What matters is not merely an individual's skills, but the match between them and the job requirement.

Similarly, venture capital businesses are a strong-link business, because they only need one or two of every ten companies to produce outstanding economic performance to more than cover the losses of the other eight or nine.

A state investment bank is a similar strong-link business, from an economic perspective. But since journalists treat it as a weak-link business that should trying to avoid losses and shouldn’t be “subsiding failure”, they become politically contentious.

In terms of economic development, for most emerging economies this is a weak link problem: make the roads better, improve the electricity supply, get the internet to work, and more cost-effectively, ensure that regulation is effective, and so on.

Inside richer economies, at least in theory, these weak link problems have been fixed, and we should be able to treat economic development as a strong link problem. But it turns out that advanced economies have created their own weak link problems by over-concentration:

As we saw in 2008, the collapse of banks led to big falls in GDP. The crisis taught us that when thinking about banks we have a weak-link problem: the priority is to avoid disaster.

He contrasts this with the failure of (UK) retailers such as Wilko and Debenhams, and suggests that here substitution means that in other areas of the economy we have a strong-link problem. I wonder if there comes a point where hyper-concentration means this is no longer true: I’m not quite sure where to go for general goods now that both Woolworths (a decade or so) and Wilko (last year) have collapsed into receivership. Especially if I don’t want to feed the aggressively anti union monopolist that is Amazon.

And Dillow thinks that the water sector is a strong link problem as well, but I’m definitely not persuaded of this. He says:

is the impending collapse of Thames Water a weak-link problem like NatWest or a strong-link one like Wilko? I suspect the latter: it doesn't matter if Thames Water can't supply water as long as somebody can; the logo doesn't matter as long as the taps still run.

No, it’s a weak-link problem. If the company that supplies the water instead also operates with a weak regulator, misaligned incentives, insufficient maintenance and repairs, and a bias toward maximising shareholder dividends, then it is still going to pour shit into our rivers the minute it rains. Solving this weak link problem is about making sure that the water companies comply with basic social standards.

But there are plenty of places where people confuse the two. There’s a whole industry that is designed to recruit “top talent”, but most of the research on high-performing workplaces suggest that they are about fair reward systems, supportive operating systems, and screening out toxic colleagues—the first is a strong link approach, the latter is a weak link approach.

There’s a whole lot more examples in the post. But there’s two points here. The first is that organisational incentives are misaligned—executives are often rewarded for strong link, risk-taking, behaviour, when they should be rewarded for ensuring good operations and minimum standards. As we saw in Boeing. Or in the Post Office.

The second point is that one of the purposes of organisations is to make choices, but they need to select for the right things. Strategy is about structure:

All institutions - be they companies, markets, government departments, elections or whatever - are selection mechanisms: they select for some behaviours and against others. The questions are: what do we want our institutions to select for or against; how well do they do such selections? and; how might we improve them?

2: Learning from the mistakes of technology reporting

At the Wall Street Journal, the technology columnist Christopher Minns has marked a decade in the role by looking back at his mistakes. It’s behind a paywall, so I’ll extend the quotes a bit.

There’s five of them:

Disruption is overrated

Human factors are everything

We’re all susceptible to this one kind of tech B.S.

Tech bubbles are useful even when they’re wasteful

We’ve got more power than we think

(And a hat-tip to Charles Arthur’s Overspill blog for spotting this.)

Disruption is overrated

The most-worshiped idol in all of tech—the notion that any sufficiently nimble upstart can defeat bigger, slower, sclerotic competitors—has proved to be a false one.

As he points out, Microsoft, Apple and Google are bigger than ever. And although disruption does happen, it just doesn’t happen very often. Because: the leaders of these large monopolies have spent a lot of money in killing off anything that might disrupt them.

One is that many tech leaders have internalized a hypercompetitive paranoia—what Amazon founder Jeff Bezos called “Day 1” thinking—that inspires them to either acquire or copy and kill every possible upstart.

(He doesn’t mention it, but they have also been largely unimpeded by regulators while they did this.)

But it’s also the case that large high margin businesses can also throw a lot of money at problems in other ways. And one of the things that this reminds me is that—as an idea— Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma is in long-term decline. It probably wasn’t ever true (at best, it was true only for a moment at the start of the technology surge), but it’s definitely now an idea that has lost its credibility.

Human factors are everything

Pop quiz: What’s the number one factor governing the pace of technological change?

If you said R&D spending, a country’s net brain power, or any of the other factors experts typically cite, you’ve made the all-too-common error of technological determinism—the fallacy that all it takes for the next big thing to transform our lives is for it to be invented.

He says that Elon Musk is the “all-time world champion of this particular cognitive bias.” Minns is refreshingly candid about his own mistakes here. He has predicted

that we were all about to abandon our laptops, that car ownership was not long for this world, and that, I kid you not, the end of food was imminent.

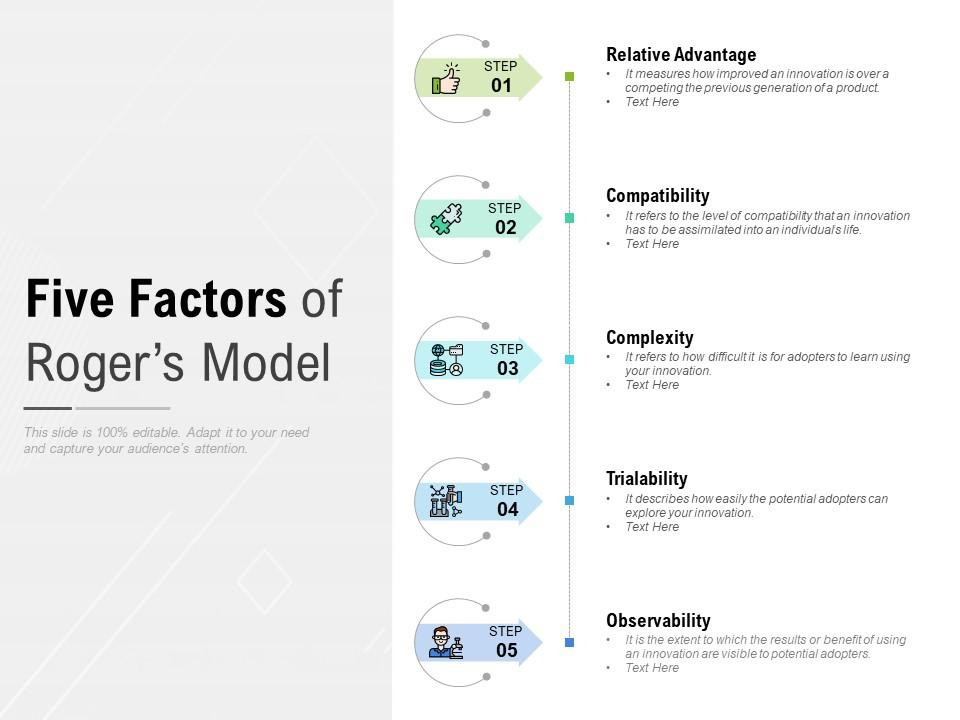

But actually, as we know from the work of Everett Rogers, the thing that determines the largest part of the uptake of an innovation is a set of five social factors (Minns doesn’t mention this, but this is what he means). What he does say is this:

The challenge of getting people to change their ways is the reason that adoption of new tech is always much slower than it would be if we were all coldly rational utilitarians bent solely on maximizing our productivity or pleasure.

(Everett Rogers’ Five Factors. Source: Slide Team)

We’re all susceptible to this one kind of tech B.S.

Tech is, to put it bluntly, full of people lying to themselves. As countless cult leaders, multilevel marketing recruits, and CrossFit coaches know, one powerful way to convince people that following you will change their life is to first convince yourself.

He doesn’t blame them for this. Tech start-ups fail all the time, and the only way to keep yourself sane is to lie to yourself about how your technology or your innovation is going to change the world.

Early in my tenure at the Journal, I also made the error of buying into someone else’s belief system about how their company is going to change the world. When inventor James Dyson explained why he had faith in a new battery company, I duly wrote it up, and years later realized just how unlikely that company had been to succeed…. Equally cringeworthy: my foray into writing about prefab construction unicorn Katerra, which later collapsed under the weight of its attempts to reinvent every part of a complicated industry.

This reminded me of one of Steven Schnaars’ recommendations in his classic book Megamistakes, about forecasting errors: ‘Avoid technological wonder’.

Tech bubbles are useful even when they’re wasteful

(P)ointing out that most new ideas aren’t going anywhere should not be confused with moralizing about innovation in general. Something Bill Gates ~told Rolling Stone~ in 2014 has stuck with me. He said that most startups were “silly” and would go bankrupt, but that the handful of ideas—he specifically said ideas, and not companies—that persist would later prove to be “really important.”

In other words, this is definitely a strong-link problem. Tech bubbles throw up a lot of junk, but they also generate some valuable innovations.

We’ve got more power than we think

The “we” here is doing a fair bit of work, but it means the rest of us: all of us who aren’t intimately associated with the tech industry.

Early in my career, I bought into the notion, espoused by science-fiction author William Gibson, that all cultural change is driven by technology. I’ve now witnessed enough of both technological and social change to understand that the reverse is also—and perhaps more often—true.

In short, we have some agency over how technology evolves, and we need to use it:

Creating and rolling out new tech without guardrails is a recipe for a world in which tech is as likely to supercharge our worst impulses, as it is to enhance our lives.

And, just contextualising this again, this is another sign that the digital technology sector is now somewhere inside the final quadrant of its 60-year S-curve, the “winter” stage, as Theodore Modis called it. Because even a decade ago, a technology correspondent, even on a major newspaper, would not have ended a piece like this in this way.

j2t#576

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

A particular brilliant issue!

The strong / weak link issue nicely illustrates the fractal nature of existence. A company face weak link issues but a (functioning) market is likely a strong link phenomenon. Really nice example of how the scale at which we analyze is one of the most important aspects of problem framing and understanding.