29 August 2023. Population | Fossil fuels

Imagining a world with declining population. // The costs of fossil fuel subsidies [#491]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Imagining a world with declining population

We’ve all been brought up to be concerned about the impact of population increases on the planet. This is unsurprising, since global population has increased from around 1.6 billion in 1900 to around eight billion now.

There was also a huge Malthusian scare in the 1970s at around the time population growth hit its maximum rate in the ‘70s. This turned out to be unfounded, at least at the time. Right now, although global population is still increasing, the rate of increase is slowing down fast.

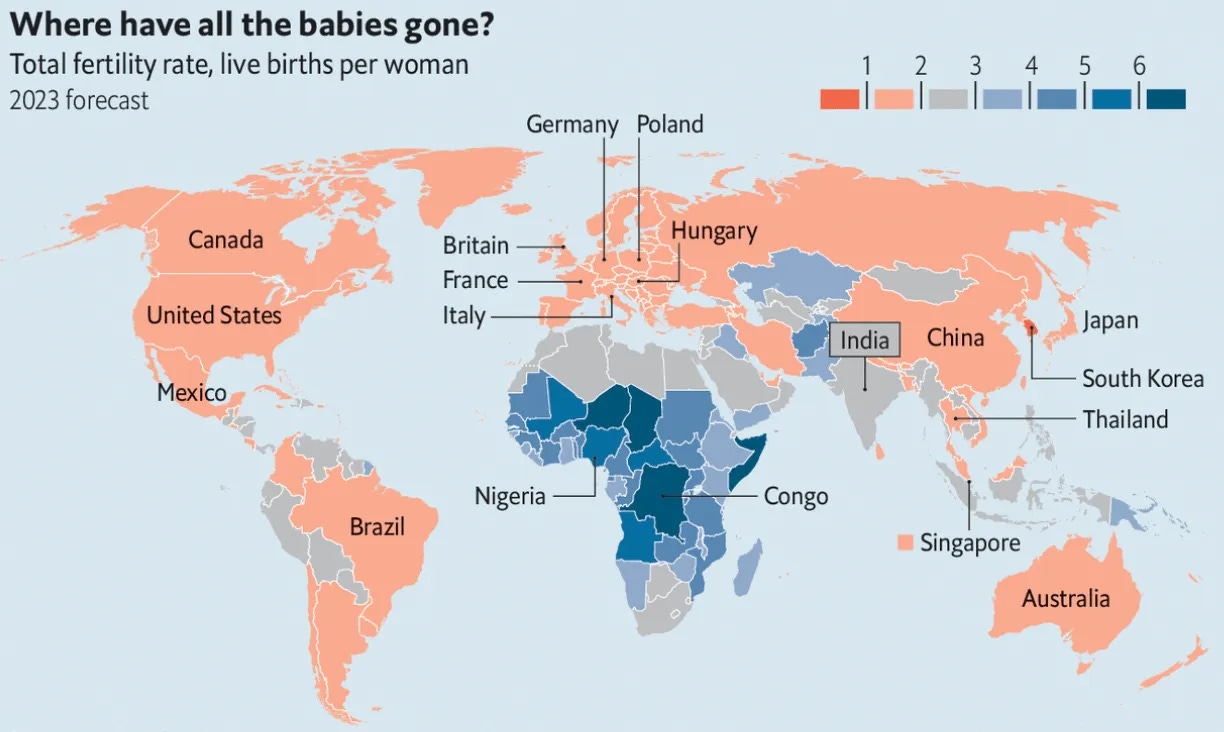

In many countries in the world, fertility rates are below replacement level, and in many more they’re hovering close to it. In sub-Saharan Africa, and in a few parts of Asia, fertility rates are still high enough to see population increasing.

Here’s a map—I think from the Economist—which conveys this. The orange countries are already below replacement rate, and the grey countries are at between two and three children per woman. The more blue, the higher the fertility levels are above replacement rate.

(Source: The Economist).

When the United Nations upped its population forecast a few years ago, it controversially assumed that fertility rates in sub-Saharan Africa would stay the same, even though they had fallen sharply in many other parts of the world.

It turns out that this assumption is wrong. Fertility rates are also falling in those ‘blue’ African countries—they are mostly following the same trajectory as in other parts of the Global South, but a few years later.

(Source: Our World in Data)

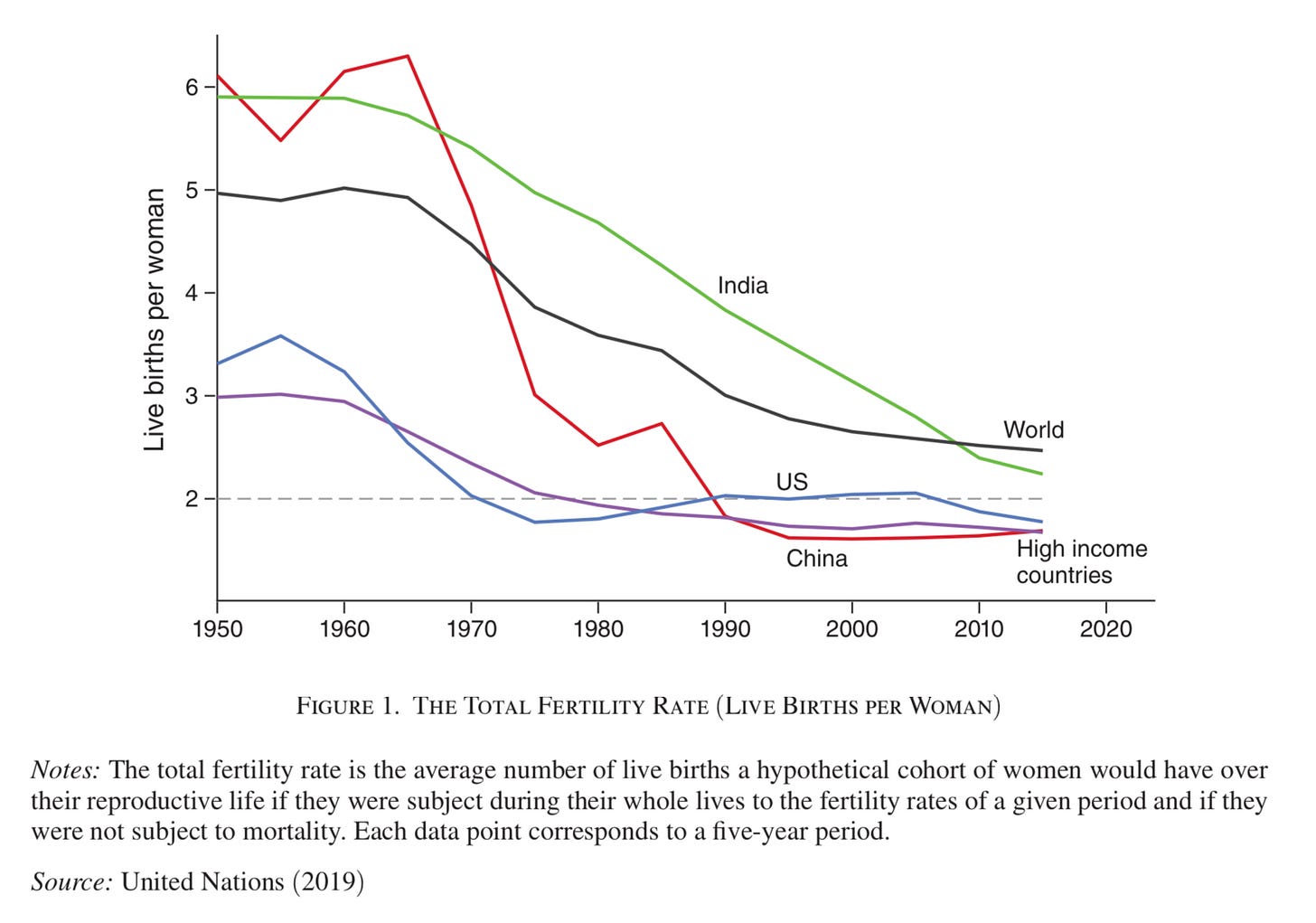

This chart comes from a newsletter by Noah Smith that is mostly behind a paywall. But the section that is peaking over the top of the paywalled fold is interesting enough.

For example, the data in this chart may be on the high side, as Smith says:

Other sources have these countries at even lower rates , and the other sources may be right. As a recent Economist article noted, every time demographers go take careful measurements in big African countries like Nigeria, they’re surprised on the downside. Africa’s population is still going to rise a lot thanks to population momentum, but hopes that it would defy the general trend toward childlessness appear increasingly far-fetched.

It’s worth pausing, and mentioning why this happening. Our World in Data points out that globally over the last five decades, or less than three generations, the average woman on the planet has moved from having five children each, to having 2.5 children each. The reasons:

In brief, the three major reasons are the empowerment of women (increasing access to education and increasing labour market participation), declining child mortality , and a rising cost of bringing up children (to which the decline of child labor contributed).

There may also be some global mimetic effects here as well. Although people tend to imagine that no-one had a clue what was going on elsewhere in the world before the world wide web arrived, first wave feminism made waves around the world in the 1970s, helped along by the spread of global broadcast media distribution.

Anyway, all of this means that the world is heading away from population growth. This suggests that countries like Japan and South Korea, which this is already happening, are possible versions of our future. It also means that competition for migrants might replace the current hostility:

Immigration can help specific countries (especially the U.S.) maintain their populations for a while at the expense of others, but as the whole world converts to small families, even that stopgap solution will become less feasible.

All of this has led Robin Hanson to imagine a set of scenarios that might reverse these falling fertility levels. His take on the data is quite stark: you can have exponential growth in population numbers, but you can also have exponential decline:

Fertility usually falls more rapidly from 4-7 down to (around) 2, then falls more slowly below 2. Rich nations now average 1.4, with some as low as 0.8. If world fertility averaged 1.4 for 25-year generations after a peak of 10 (billion), humanity would go extinct in 1660 years. If fertility instead averaged 1.0, that would take only 830 years.

He doesn’t think an extinction scenario is likely, but he doesn’t want to rule it out. Even decline is problematic, because he is persuaded that shrinking populations lead to shrinking economies, and shrinking economies don’t innovate, and has argued this case in a previous post. He also points to a paper in American Economic Review that makes the same argument, also in the context of declining population, but with more and better equations and a summary of the literature.

I’ll come back to some of this lower down, but let’s start with Hanson’s scenarios, which are trying to identify circumstances in which fertility might increase again.

There’s sixteen of them, and they’re short. I’m not going to go through them all, but will try to identify commonalities. There are really only a few variations within the sixteen.

One is that increasing poverty creates circumstances in which the traditional rationale for more children re-emerges, as a kind of economic insurance policy for the family. Some of the scenarios feature ways in which this might happen.

A second is that health or medical technology allows child rearing to be done over a longer period of life, which removes some of the biological constraints.

A third set involve a reversion to more traditional gender roles, in different ways.

A fourth group is some kind of collectivisation of child rearing: “robot nannies” (scenario 7), for example, or “parenting factories” (scenario 11) where children are raised collectively. This is the closest the scenarios get to suggesting that fertility levels might increase with actual gender equality.

The conclusion to Chad Jones’ American Economic Review paper says:

From a family’s standpoint, there is nothing special about “above two” versus “below two” and the demographic transition may lead families to settle on fewer than two children. The macroeconomics of the problem, however, make this distinction one of critical importance: it is the difference between an Expanding Cosmos of exponential growth in both population and living standards and an Empty Planet, in which incomes stagnate and the population vanishes.

There’s a lot of questions going on here, but also a lot of issues. Increasing global population has got us into the position we are in today, with a climate emergency and a biodiversity crisis. So a declining population is a good thing, but it matters how we get there.

Secondly, as a species, we have been used historically to a globally flat population, and also a globally increasing population, but not a globally declining one. This comes with an ageing population, so we’re in new cultural territory as a species. Old frames of reference may not apply.

Third, some of the assumptions about innovation here draw on economic models that by design work better in a world of growth. A declining population is a form of complexity reduction, and forms of innovation in this world might also be about reducing complexity. As Hanson notes, these future generations will be able to work with a large stock of capital, and a large stock of knowledge.

(My thanks to Walker Smith for the link to the Robin Hanson scenarios post).

2: The costs of fossil fuel subsidies

There are, generally, three questions you need to ask when you’re scanning for signs of change. They are:

Does this confirm something that I know?

Does this change something I know?

Is this new?

The futurist Wendy Schultz adds that with the third question, you also need to ask if this is “new to you”, or “new to everybody”, although in practice the class of things that is new to everybody is both tiny and typically a long way away from having an impact on the world. As you discover when following the current excitement about room temperature superconductivity.

But the first question also has some nuance about it. You can read something that doesn’t change what you know, but it is being said by someone whom you wouldn’t expect to be saying it. Which is also one of the reasons why futurists also use S-curves.

This is a long way in to noticing that the ‘Chart of the week’ on the International Monetary Fund’s blog last week was about fossil fuel subsidies hitting record levels. Here’s the chart:

The blog post is based on a recent IMF working paper, with supporting country data, which is freely downloadable.

Fossil-fuel subsidies reached seven trillion dollars worldwide last year. Some of this is in the form of what the authors call “explicit subsidies” to users, to reduce direct energy costs. The rest is in the form of “implicit subsidies” the majority of which is in the form of environmental costs that aren’t paid for by producers, including global warming and air pollution. $7 trillion is obviously a big number, and the authors put the scale of it into context:

As the world struggles to restrict global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and parts of Asia, Europe and the United States swelter in extreme heat, subsidies for oil, coal and natural gas are costing the equivalent of 7.1 percent of global gross domestic product. That’s more than governments spend annually on education (4.3 percent of global income) and about two thirds of what they spend on healthcare (10.9 percent).

It’s also worth noting that this $7 trillion figure can be thought of as an estimate on the low side. The authors made the assumption that the costs of global warming “are equal to the emissions price needed to meet Paris Agreement temperature goals”.

If instead they had used the “social cost of carbon” price calculated in an article in Nature last year, the figure would be almost twice as high.

Different fossil energy sources have different levels of subsidy. From the working paper executive summary:

Differences between efficient prices and retail prices for fossil fuels are large and pervasive across fuels, but especially for coal. Globally, 80 percent of coal consumption was priced at below half of its efficient level in 2022.

(‘Efficient’ prices are prices without subsidies: the definition is explained in the footnote).1

The authors expect the explicit subsidies to fall as energy prices continue to decline from their peak last year, but implicit subsidies to rise as developing countries increase their consumption of fossil fuels toward the levels of advanced economies.

The results of fossil fuel subsidies are three fold:

“Environmental damages like global warming costs and local air pollution deaths are far too large;

“Governments rely extensively on more distortive taxes like taxes on work effort and investment and too little on more efficient ones like taxes on fossil fuels, or they do not adequately fund public investments, for example for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); and

“... poverty reduction objectives are undermined, as most of the benefits from inefficiently low fossil fuel prices accrue to better off households.”

There are therefore significant benefits to removing fossil fuel subsidies that go beyond the environmental benefits. In the blog post they summarise them this way:

We estimate that scrapping explicit and implicit fossil-fuel subsidies would prevent 1.6 million premature deaths annually, raise government revenues by $4.4 trillion, and put emissions on track toward reaching global warming targets. It would also redistribute income as fuel subsidies benefit rich households more than poor ones.

Of course, removing fuel subsidies is a tricky business. Like food markets, it is the kind of thing that leads to protests, riots, and governments being brought down. The health and environmental benefits appear in the longer term, but the costs appear in the short term. But you can design the transition in ways that helps poorer households, which reduces the pain.

My slight surprise at all of this is that the International Monetary Fund has been regarded by its critics for several decades—not wrongly—as an enforcer of neoliberal market policies. Sure, it softened this approach in the wake of the global financial crisis, although Greek readers might have a different view. All the same, rummage around on the IMF site and you will find some articles concerned that neoliberalism increases inequality, which undermines growth.

And this IMF analysis on fossil fuel subsidies is still very much a market-based analysis, based on economic modelling. The thing that’s changed in the meantime is that the view of the scope of what needs to be included when looking at markets—in institutions that are still central to how the global economy works—has started to change.

j2t#491

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The economically efficient price for a fossil fuel product is given by: (unit supply cost + unit environmental cost) × (1 + general consumption tax rate, if applicable).

Peter Curry suggested that this breakdown of the subsidies was worth including here:

“Underpricing for local air pollution and global warming account for nearly 60 percent of global fossil fuel subsidies and underpricing for supply costs and transportation externalities (such as congestion) explain another 35 percent (the remainder is accounted for by forgone consumption tax revenue).”