Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

The idea of building cities on the sea has a long pedigree: apparently the Aztecs thought about this, and inevitably Buckminster Fuller knocked up a design in the 1960s. But with sea levels rising, and 40% of the world’s population living in coastal regions, the idea is becoming more pressing.

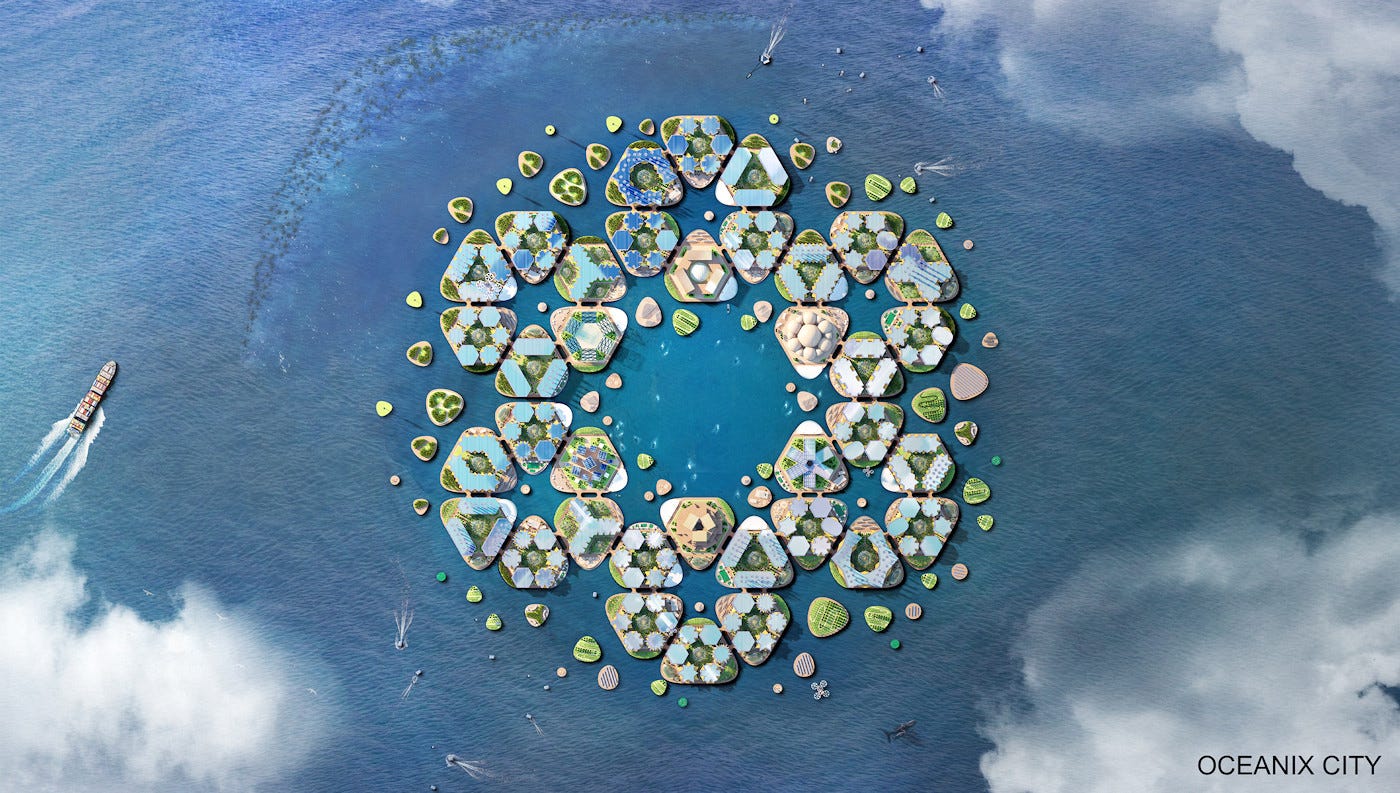

So it’s worth noting a Fast Company story about a presentation by Oceanix the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) to the United Nations earlier this year—partly because there are features of this design that look as if they might work.

And just to be clear, this is a world away from the “seasteading” proposals floated by various Silicon Valley sociopaths, which are more about avoiding paying tax, and which in practice would be like a waterborne version of Snowpiercer.

Image: BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group

The Oceanix design, for a start, is modular, building up from 4.5 hectare islands that can each house around 300 people—and can then be connnected together:

Combining six of these islands forms a small village around a central open port, with each island having some kind of dedicated communal use–like healthcare, education, spirituality, exercise, culture, and shopping. Then, if you continue to scale up and loop six villages together, you end up with a small city of 10,800 people. Outside the floating city there would be small uninhabited islands with dedicated purposes, like to collect energy from the sun or to grow food. These would also double as a buffer against waves and wind.

The Fast Company story notes five features of the design which are worth summarising here:

Drinking water comes from the air (rain) and the ocean (through desalination). Rain is better, so the design collects evry drop of rain that lands on the island.

The islands would grow all their own food. So they’d be almost entirely vegetarian—and have to have a circular food economy.

Resource efficiency also leads to a “sharing economy”. This would be based on renting not owning, partly to manage resource flows.

Transport would be low impact. The design allows for 60% of trips to be made by walking or cycling, but there’d also be some electric boats.

Everyone would have a personal energy budget—their share of the energy generated by the city. Electric transport makes a dent in this, but the biggest consumer of electricity is agriculture.

Last week I mentioned in passing that our present cities have a vast ecological footprint, and Herbert Girardet’s idea of ‘Ecopolis’, which brings this down. So the Oceanix/BIG project also acts as a valuable thought experiment: what happens if a city has to live inside its own footprint?

There’s much more detail in the Fast Company article.

Oceanix was founded by the entrepreneur Marc Collins Chen, who was Polynesia’s minister of tourism for a while. Obviously Polynesia will be one of the first casualties as seas rise, so the floating cities project was based on a response to a real problem. The Oceanix website is also worth a visit.

Image: BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group

#2: The long afterlife of vinyl

Tom Gatti had a piece in the British New Statesman magazine (tightly metered paywall) on the afterlife of vinyl as a recorded music form. (He’s recently edited a collection in which various luminaries wrote about records that they “cherished”.)

I’m not going to discuss those selections. Gatti’s article is more interesting on the afterlife of vinyl, a dominant recording form for maybe 40 years, and written off by many as it was replaced by CD and then streaming became dominant.

His story starts when he discovers Michael Jackson’s Thriller as a child, both the last great swansong of vinyl and also, still, the largest selling long-playing record ever.

By then, at least technically, the LP was fifty years old (it was invented in 1932) but it took a while for materials to be stabilised and for record companies to agree on a length:

After the Second World War, Edward Wallerstein, the president of Columbia Records, was offered prototype discs of between seven and 12 minutes per side. But after a week exploring the label’s backlist, he settled on a figure of at least 17 minutes per side: enough for most classical works to be contained on a single record. The final product was 12 inches in diameter and 22 and a half minutes a side.

The history from there is familiar: it took two decades for musicians to work out the possibilities of the new format (Pet Sounds, then Sergeant Pepper). In 1969, long-players outsold singles for the first time.

(Image by Nigel Featherstone)

The piece traces the familiar cultural history of the rise of the CD, followed by the emergence of streaming. The CD gets a bad press:

The compact disc gets a bad press. David Hepworth describes buying a CD in a megastore in the Nineties as “more akin to an act of surrender than to an expression of devotion”. When Bret Easton Ellis imagined a yuppie serial killer, he made him a CD collector: in American Psycho, Patrick Bateman is an obsessive fan of Phil Collins and Huey Lewis and the News and takes great care of his compact discs

But it also created a boom in long-format music—“In 2000, 942.5 million CD albums were sold in the US, compared to 344 million LPs at vinyl’s peak in 1977. “ But while music executives were worrying about the risks of bootleg CDs, they were blindsided by streaming. And streaming represented the return of the single track—with some added cultural tweaks.

But vinyl has survived: one in eight long-format records sold in 2019 were vinyl and weren’t just nostalgia, since top-sellers included Billie Eilish. A plant in the Czech Republic is pressing 24 million records a year.

Gatti thinks that this is because we like stories, and the long-format does this in a way that Spotify never can.

You might recall the thrill of the concerts in the 2000s in which artists from Brian Wilson to Sonic Youth would perform an LP in its entirety, or you might have joined Tim Burgess’s lockdown album-listening parties on Twitter... (l)isteners are returning to the album as an unbroken artwork: something with an emotional and sonic arc, to be played from start to finish without interruption.

j2t#12x

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.