Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The future of skills probably isn’t about AI

I’m talking this afternoon about the future of skills on a panel organised by Not9To5 and RSA Scotland. (There may still be time to book).

I’m going to argue three things.

One: That the fears of the ‘robo-apocalypse’ are wildly exaggerated. Yes, people will need to learn how to do their jobs with digital augmentation, but working with machines has been a feature of work since at least the Industrial Revolution.

One of the problems here is that we’re still living in the shadow of the 2013 Frey and Osborne paper and its figure that 47% of all jobs were at risk from automation, but as I have written here before, there are multiple reasons why that was wrong. Their timescales were vague; they didn’t allow for the evolution of jobs over time; they treated jobs as single things rather than as bundles of tasks; they didn’t allow for new jobs created by digitisation. The list goes on. The at-risk figure shrinks every time there’s a new report.

Two: the way the city works is central to how jobs evolve (and this has probably been true since Sumerian times). I have done some research on this for a chapter that will be published in Planetary Cities, edited by Jose Ramos and Bharat Dahiya, and started with Geoffrey West’s analysis of the city as a system in Scale.

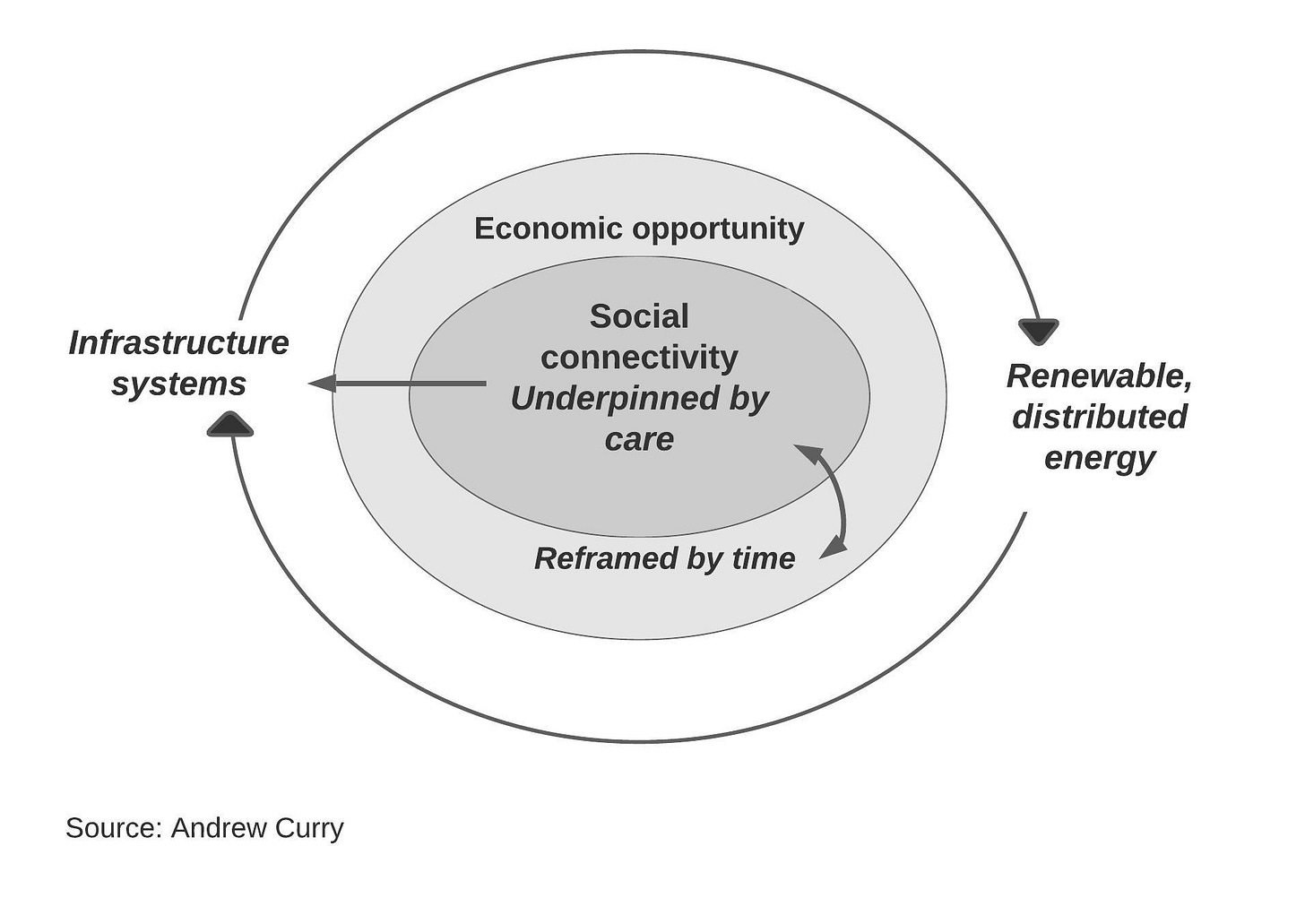

The current system has a vast footprint; infrastructure and energy engage in a mutually reinforcing dance with each other.

But this system is oil-dependent and increasingly vulnerable, not least because it is getting worse at reproducing its social systems. So there’s a new version—currently fighting with the old one—in which the footprint shrinks (so more local energy and food production, and probably more repair, and less distribution and warehouses). Herbert Girardet described this as the shift from Petropolis to Ecopolis. At the same time, care needs to change so the city can look after the people who do the work, as well as the increasingly ageing population.

And there’s also new battle going on about working time, which changes the way people think about jobs and skills. We’re seeing this in experiments about the four day week and the five day hour.

Three: we might be at peak system complexity. And if this is true, the system will either collapse or simplify itself. We’re already seeing signs of this. The organisations that are growing profitably are organisations that have decentralised themselves, whether in social care (such as Buurtzorg) or in appliances (Haier). In fact Corporate Rebels has a neat graphic and article about the job roles in Buurtzorg. These are probably the skills of the future.

#2: Degrade yourself

(Pilar Quinteros, Janus Fortress: Folkestone. Photo by Thierry Bal)

My attention was caught by a piece on the England’s Creative Coast website about a new sculpture that’s been unveiled overlooking Folkestone, a port town on the south of England. The sculpture, called ‘Janus Fortress: Folkestone’ is based on the Roman god, and there’s a certain amount of art curator type talk in the article about how the sculpture faces both ways, out to sea and back over the town, while representing ‘the duality of borders’ etc.

But I was more interested in the fact that it will degrade over time. The Chilean artist, Pilar Quinteros, has made it out of a plaster composite that resembles the nearby chalk cliffs, and so it will be affected by weather, and people:

Quinteros cedes sculptural control to her materials through her work’s built-in fragility and metamorphosis, and in this way her work suggests an acceptance of mortality and of not being able to control life. It is, she says, “a monument to uncertainty”.

(Pilar Quinteros, Janus Fortress: Folkestone. Photo by Thierry Bal)

j2t#120

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.