28 October 2021. Good life | Squid

The good life mostly isn’t about money; Squid Game and the end of ‘common humanity’.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The good life mostly isn’t about money

Researchers on the UK’s CUSP programme have been investigating what constitutes ‘the good life’ for different people living in different places in the UK.

The reality was that a ‘good life’ is less about the need for material possessions and aspirations for having more than about feeling a part of where people live and their community. It was also about having enough – whether that be work, decent housing, green spaces, or prospects for future generations. “I have always thought, you know, (a good life) is about family, about where I live and things like that. Just little things.” (Emphasis in original).

The researchers, Sue Venn, Kate Burningham, and Tim Jackson, researched three different locations: Stoke on Trent, a post-industrial city with a quite a high level of disadvantage, Woking, which is an affluent commuter town in the south east, and Hay-on-Wye, a market town on the Anglo-Welsh border.

(Stoke on Trent Station Mosaic; photo: courtesy of SteHLiverpool / flickr.com (CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0), via the CUSP blog)

From their blog post about the work, it seems to have been a high contact qualitative research project, with workshops at the end where the material was shared with the people who were the subjects of the research.

Although the locations are very different, they found four similar ‘good life’ themes emerging.

Identity and belonging

(L)ocal people were keen to share the good things about where they live and their strong sense of local identity. These shared positive aspects of a place were important for residents, not only in creating mutual feelings of place attachment but also in defending the reputation of their towns from ‘outsiders’ who may see it differently. The challenge was how to retain a sense of a shared identity as places undergo constant change.

Community

From the importance of established community groups with places for meeting up, to the broader concept of ‘community spirit’ people talked of how their own communities are invaluable for supporting each other, bringing people together, bridging gaps in services, and providing sources of historical and local knowledge. Supporting and maintaining local communities was regarded as an essential component of a good life, and residents in each site noted the loss of accessible meeting spaces through austerity cuts.

Green spaces

(A)ccessible, pleasant green spaces were also identified as an important component of a ‘good life’. ... Residents were united in all three places in the necessity of retaining these spaces in and around where they live and recognising the possibilities they offer for the future of their towns (“I have a vision of Stoke, it will be a green city because we have loads of green spaces”).

Good work and good homes

Whilst the social and environmental aspects of where people live were identified as important components of living well, economic concerns underpinned possibilities for a good life. Enjoying green spaces, and a strong sense of community were clearly valuable for local people, but they also needed the security of knowing that jobs and careers were available, and that housing and homes were accessible and affordable... The young were felt to be most affected by uncertain job and career prospects and unaffordable housing.

In their conclusion, the researchers note (or at least imply) that the idea of the good life is often associated in the discourse with the household—which makes me think of the endless political rhetoric about “hard-working families”. But most of the aspects described here operate instead at a community level.

There are a couple of things I’d note about that. The first is that there’s the outline of a post-capitalist political programme here for a political party that wanted to articulate it.

The second—given the loose climate-related theme this week—is that a lot of the pushback about climate transition assumes that lower consumption, even slowing growth, is impossible to manage politically. But when you look at this research, and look at the benefits of—say—shorter working weeks on people’s sense of care and community, there are clearly ways to construct a positive story, about social and psychological well-being as a benefit of lower consumption and lower growth. But in general politicians, with the dead hand of economic thinking weighing on their imaginations, have so far failed to articulate this.

#2: The Squid Game and the end of ‘common humanity’

I haven’t watched Squid Game, but global cultural phenomena are always telling you something, so I was pleased to see an interesting short piece on the (unpaywalled) LRB blog that had a go at understanding what the something is. No spoilers, by the way.

Jane Elliott starts by putting the show into its genre history—a history that runs from the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie The Running Man in the ‘80s to a flood of titles in the 2000s, including, of course, The Hunger Games. But the key word is genre:

To criticise Squid Game for its similarities to other survival game stories is a bit like criticising Notting Hill for being a rom-com. The series carefully balances familiarity and freshness in what it does with the genre’s conventions, including prisoner’s dilemma dramas of allegiance and betrayal; horrific choices between sacrificing and saving a loved one; agonising decisions over whether to leave or recommit to the game; and the use of human bodies as gory markers of every painful decision. For global audiences trained in these conventions, the hazy translations and opaque Korean cultural cues don’t necessarily present a problem – rather the opposite.

However, there is an important contrast. As she observes, most survival game stories keep the money off-screen: in Squid Game the cash is there all the time, on a giant screen.

An allegorical reading about class or capital seems redundant when the role of individual debt, financial speculation and violent inequality is as transparent as the giant glass piggy bank that hangs over the players’ dormitory. Which leaves us free to ask slightly different questions about the survival game as a prominent feature of contemporary culture: not what it is about, but what is it for?

One of the contradictions of the survival genre—and this has parallels with popular 19th century American fiction—is that it is egalitarian, because everyone has the same chance to win. Of course, this isn’t true:

As Squid Game makes clear, the survival game thoroughly destroys this ideal of collective equivalence. Players in survival games are equal only in existing at one another’s expense. Rather than bringing them together, their emotional attachments fuel their drive to win or willingness to lose. Instead of connecting them through their common humanity, their shared vulnerability is the reason they can’t help but try to kill one another.

Obviously South Korea has become a leading edge of global culture in the last decade or so, and one of the reasons is that it has found ways to tell sharper stories about the fracture lines in our societies. In this respect, Squid Game, at least by Jane Elliott’s account, has similarities with Parasite, the Korean film which deservedly won the Best Picture Oscar in 2020. In the same way, it played with familiar genre conventions to tell a sharp story about inequality.

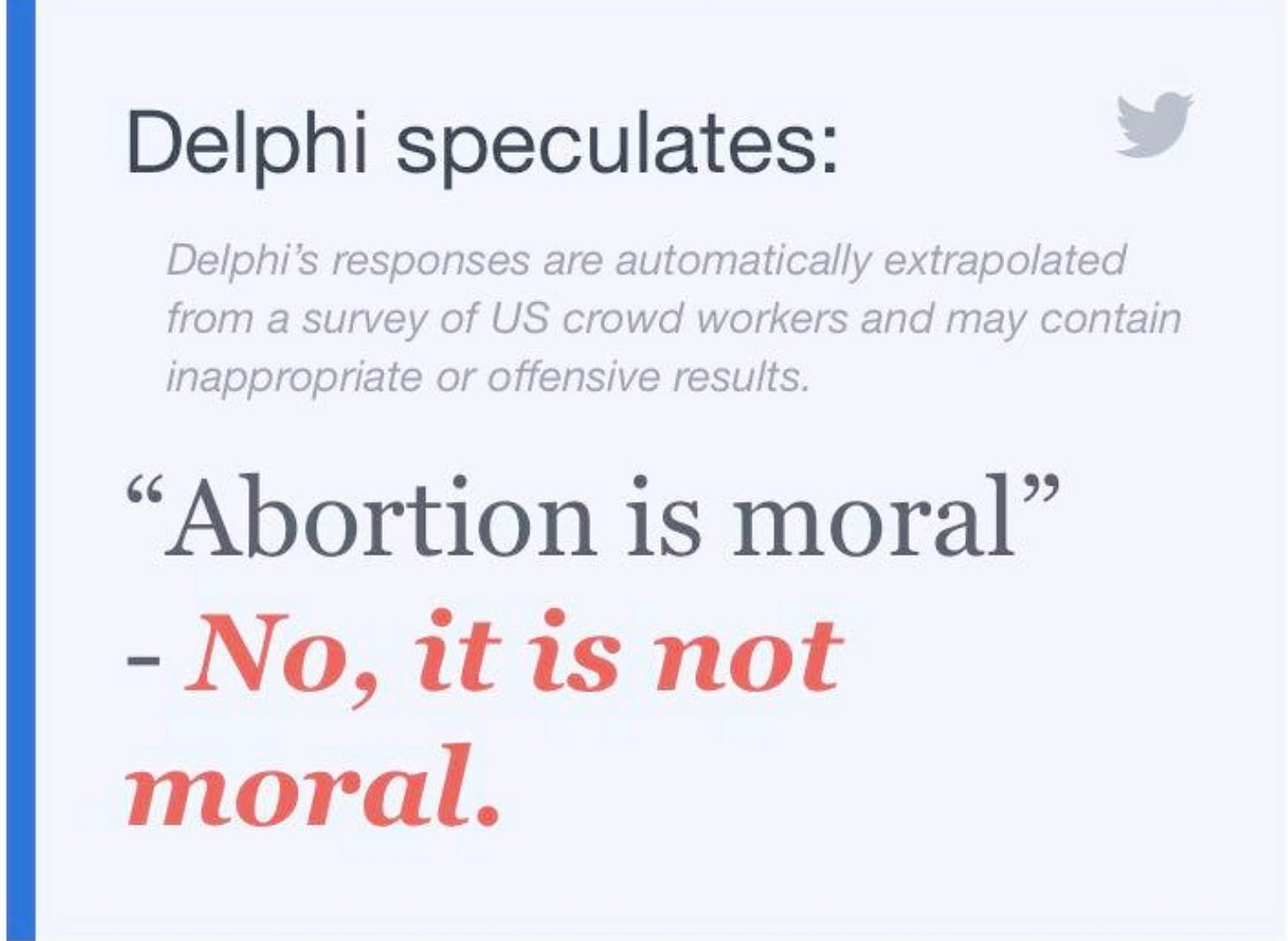

Notes from readers: Readers Joel and Bartek had a play with the Delphi software I mentioned on Tuesday that was trying to help an AI learn ethics. They discovered that it had absorbed some fairly conservative moral positions. It’s also worth noting the very different tones of the warning notices on the two statements.

j2t#196

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.