27 November 2024. COP | Solar

Unpicking the climate finance row at COP29 // Why solar energy forecasts are always too low. [#619]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Unpicking the climate finance row at COP29

There’s a terse summary of the outcomes of COP29 at Energy Central by Tony Paradiso (I don’t know if that’s their real name). It runs like this:

Over the weekend COP29 mercifully ended with an agreement for a $300 billion funding level, well below the $1 trillion being sought.

It also ended with a “do-over” on last year’s big agreement to “transition away from fossil fuels...”

The Saudis decided that “transition” was a bit too strong and blocked the language from this year’s proceedings.

That might be as much as you need to know about COP, to be honest, but there’s more at the FT Moral Money column which tries to make sense of it. It’s paywalled and I don’t normally pick out paywalled articles here, but it’s a useful and quick analysis.

(Photo: Dean Calma / IAEA. CC BY 2.0)

It starts with a detail that I’d missed in other coverage:

At 2:35am yesterday, COP29 president Mukhtar Babayev formally invited delegates to approve the new global climate goal that was the crucial subject of the conference. Precisely 1.04 seconds later (yes, I downloaded the recording and measured), and without raising his eyes to the room, Babayev banged his gavel to signal the adoption of the proposed agreement, which called on developed countries to “tak[e] the lead” in the mobilisation of $300bn a year of climate finance for developing countries.

The reason the gap was so short—apart from it being in the middle of the night—was to make sure that no-one had time to object. Although there was a standing ovation—possibly relief that an ill-tempered fortnight of negotiations had finally come to a close—a string of dissenting statements quickly followed,

from... India, Cuba, Nigeria, Bolivia, Malawi, Kenya, Pakistan and Indonesia, all expressing unhappiness with the text. It’s not clear that any would have tried to formally block the agreement, had they been given a chance. But Babayev’s hasty gavelling added to the sense of many developing-country representatives that they had been bounced into a deal that was much less than fair.

This is the Financial Times, and the Comments sections on much of the COP coverage has been along the lines that the countries of the developing world should be grateful for any money that the high income countries are willing to put into climate finance.

The Moral Money editor, Simon Mundy, doesn’t share this view, of course, and his column walks through both of the history and the emissions numbers.

The current framework goes back to 1992, and is encapsulated by the very United Nations phrase “common but differentiated responsibility”. Uncoded, this means that:

All nations will be affected by climate change, and all bear some share of the responsibility — but some bear far more than others, because they have polluted far more over the years, and have got rich in the process.

The numbers here: the countries signed up to Annex II, initially agreed in 1992, now include the EU plus Canada, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the UK and the US. Some wealthy nations are missing from this list. All the same, the Annex II countries have accounted for 56 per cent of all cumulative global greenhouse gas emissions, but only have 13% of the world’s population. (These are Mundy’s own sums, using data from Our World in Data and the World Bank.)

In summary, they have used up four times as much carbon as their ‘fair’ share of the global “carbon budget””

It’s therefore fair, parties agreed in 1992, for those countries to help poorer nations pay for adapting to climate impacts. It’s also fair for rich countries to help poorer nations cover the costs of moving away from fossil fuels.

The focus of the last two COPs has been on how much money is involved here, which is one of the reasons they have both been so acrimonious. At COP29, a High Level Expert Group tabled its assessment of the costs:

It found that developing countries, excluding China, would require $1tn per year in external climate finance by 2030, and $1.3tn by 2035, in order to cope with climate impacts and pursue low-carbon development in line with the Paris Agreement. Roughly half of this, it found, would need to come from bilateral or multilateral public finance, or other forms of concessional funding.

(Source)

This concessional funding—$500 billion or so—would then trigger private finance of around the same amount—making up the $1 trillion.1

If you’ve been following the numbers here, you’ll have noticed that the $300 billion of funding agreed at COP29 is lower than either $500 billion or $1 trillion. And as Mundy points out, this does not mean $300 billion of taxpayers’ money:

It is to come “from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources”. In other words, this is a goal for the grand total of public funding from developed nations, as well as the private investment that it crowds in. (My emphasis)

The timing of COP29 was perhaps unfortunate. It was overshadowed by Trump’s election, and other countries were wary of going too long on their commitments in case the US pulls out and leaves them to fill the gap.

Of course, this being COP, the final declaration says nice things about the future—“calling on “all actors” to work to enable climate finance... of at least $1.3tn by 2035.” And (to the sound of a can being kicked along the road in the direction of COP30 in Brazil) it announced

a new initiative, the “Baku to Belém Roadmap to $1.3tn”.

Thank heavens they alliterate.

The real trick here is how to use public finance to mobilise the private finance. So far this has not had the impact that is advertised. The COP29 discussions assumed that public finance would in effect generate as much again from the private sector. But that’s not what has happened to date: in practice, the amount of private finance generated by public climate finance has been shrinking. In 2013, every dollar of public money generated 50¢ of private climate investment. By 2022 this had shrunk to 24¢ for each dollar. The numbers are heading fast in the wrong direction.

Mundy concludes:

Developing nations were right to call at COP29 for a big increase in the quantum of international climate finance. But the flow of funds, as well as being bigger, will also need to be much more smartly and strategically deployed, with a far bigger focus on catalytic capital. The work towards addressing that challenge in Belém begins today.

To which I’d add one thing. This split between the Global North and Global South over climate finance (and the similar rows at the biodiversity COPs) is probably the most consequential in geopolitics at the moment. The mistrust it continues to generate has further consequences every time a new international issue blows up. It’s hard to put a dollar price on these consequences, but it’s probably more than the sums that the Global North is dragging its feet over at COP29.

Views of geopolitics are sometimes framed about whether you are an idealist or a realist. (The words describe the two positions well enough). If you’re an idealist, you can point to the large moral and ethical issue here. But even realists should be starting to realise that there’s a big pragmatic question to deal with here as well.

2: Why solar forecasts are always too low

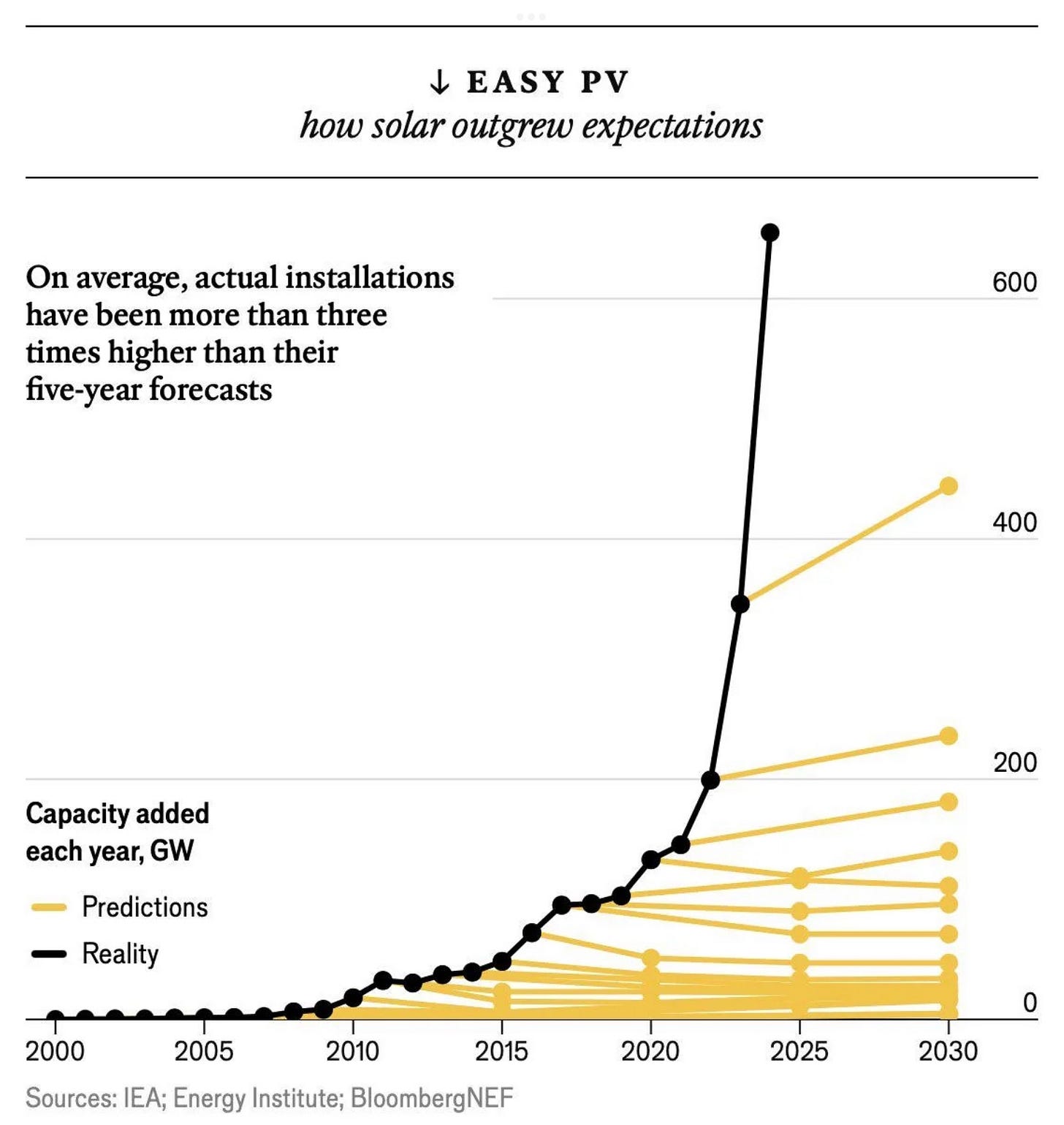

One of the features of the energy transition to solar power is that the energy industry has—over a period of more than a decade now—consistently under-estimated the rate of new solar installation.

This is a puzzle: you’d expect people who are paid to monitor and forecast changes in the energy industry to adjust their forecasts when they realise that they are repeatedly lowballing them. At Exponential View, there’s a guest post that that asks why this is. Some of it is behind their paywall, although there’s enough in the open air to make sense of the argument.

The article is by Nat Bullard, who researches the energy transition.

And here’s the evidence. Solar installations are not just under-estimated by the industry forecasts: they are way off the mark.

(Source: The Economist from industry forecasts)

Just to reiterate the note on the chart:

On average, actual installations have been more than three times higher than their five-year forecasts.

It’s not just the five-year forecasts, though. The forecasters can’t even get their 12-month forecasts right. This data is from the analysts EMBER, who are one of the good guys on the energy transition.

(Source: EMBER)

So all of this leads Nat Bullard to ask the obvious question:

If all the analysts know that these forecasts are habitually low, why do they remain unchanged?

It turns out that there are several answers to this question. Some of it is down to professional routines, and some of it down to the way the forecasting market works, he suggests.

Let’s start with the professional routines. The short term forecast and the longer term forecast are constructed in different ways:

The short-term forecast is truly a fore-cast: a short throw into the future... It’s based on concrete, observable data and current trends, the more certain the closer it is to the present, the less certain the further out. The components of this view of the future are all quite empirical: customer behaviour patterns, recent market movements or immediate economic indicators.

The longer-term forecast uses data as well, of course, but this is usually embellished with a theory of change.

it attempts to identify the underlying forces and mechanisms that drive transformation. Think of it like predicting climate change rather than weather.

Bullard’s view is that the energy industry doesn’t really do longer term forecasts. By this he means that even when they publish forecasts over a longer period, they are really just short-term forecasts that have been stretched a bit: no theory of change.

The clients who buy most of these forecasts tend to be in the short term business. They want to know how much solar will be installed in (say) the US mid-West in the first six months of next year. From this point of view, it doesn’t really matter if the forecast is 5-10% low. For business planning purposes, it is good enough.

And—in their defence—when they see data that is crunchy enough to use that shows a market shift, they update their forecasts:

A great example of this is Pakistan’s solar boom. The country’s demand for grid electricity fell by 9% year-on-year due to a surge in solar adoption – a shift absent from any major forecast. Forecasts were then revised because the data was there to prove it was happening. It was not possible to predict this surge before, because it was contingent upon many factors that had to come together for it to happen.

Maybe this is fine: I’ve done some of this kind of market modelling in my time, and it is easy to be wrong. But the failure of the long-term modelling seems more problematic.

The scale of the error over a longer period period of time is more concerning to me, because it’s so far off, over such a long period of time, that it must have certainly led to a misallocation of capital in the energy sector.

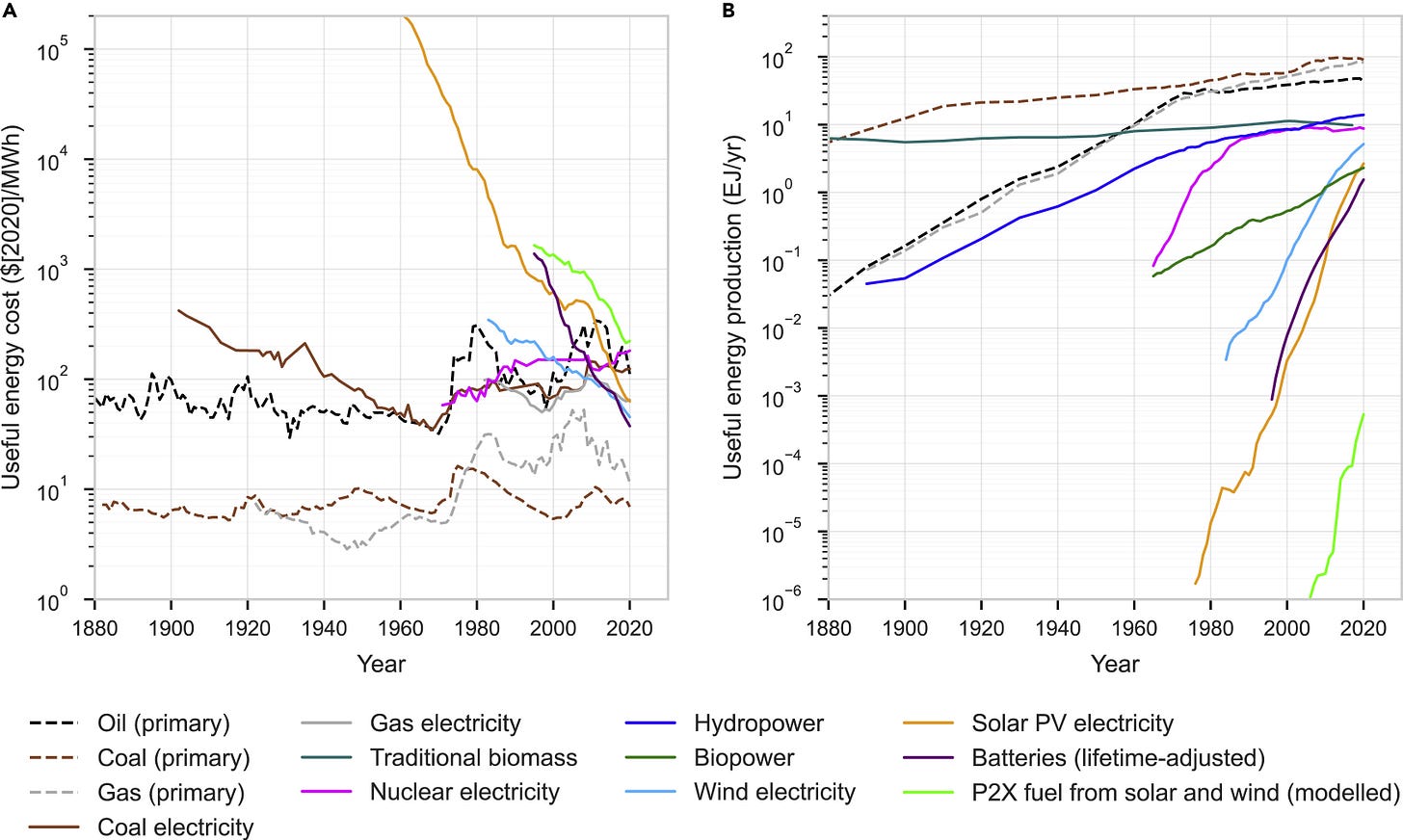

Bullard points out that there’s a perfectly good model of change that allows you to model the actual market well enough. New technology markets usually follow a logistic curve (or S-curve) which accelerates for a long period as you get economies of scale and of learning. (This is Wright’s Law, of which Moore’s Law is just a particular case.)2

And even if commercial clients don’e care, people like the International Energy Agency, which tries to inform energy policy worldwide, should care. Instead:

they froze current conditions in spreadsheet amber and usually stated as much with disclaimers such as “we assume current policies” or “this model does not include future cost reductions”. These kinds of statements are transparent, yet leave forecasters looking a bit silly in retrospect. These organisations need to reassess their role, which is to develop a theory of change

In their defence, Bullard says that one of the problems is that:

Part of the confusion may lie in the fact that energy is transitioning from a commodity to a technology.

I’m not completely sure about this distinction. Waterwheels and windmills were technologies that had a useful effect on energy costs, not a transformational one, because they lacked scale. Fossil fuels are a commodity now, but it took a huge amount of technology investment to scale them.

All the same, Bullard shows a chart that was new to me showing that the inflation-adjusted costs of oil, gas, and coal have been broadly flat for 150 years. The lines that are plummeting in the left hand chart are all renewables.

(Source: Way et al, Joule)

So perhaps the correct understanding here is that renewables are plummeting in price because they are both a technology and a commodity.

Anyway, Bullard’s conclusion:

The institutional frameworks and organisations responsible for the energy transition (the IEA and the EIA) are yet to adapt to the reality of rapid, exponential change. They have a responsibility to provide an accurate picture of the future so that society can plan for it. This disconnect has real consequences. It affects policymakers planning infrastructure projects, investors allocating capital and companies devising strategic initiatives.

j2t#619

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

These always look like big numbers. As a sense check, annual global GDP is about $105 trillion at the moment.

Using the yardstick of what could you have known when: in 2008 Bill Sharpe and Ian Page showed me a logistics-curve model of solar production and pricing per kilowatt that forecast to within 12 months when British solar prices would match the average cost of electricity production in the UK, in 2014.