Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

Have a good weekend!

1: The rise and rise of BookTok

I didn’t know that #BookTok was a thing until I noticed a story in one of my feeds that said that TikTok was the new digital media partner of the Hay Festival, which opened yesterday.

This was how Hay announced it:

The strategic partnership will see TikTok support Hay Festival as it looks to reach more diverse audiences via TikTok's easy to use product and supportive community. With discoverability and creativity hard-wired into the platform the opportunities for upcoming and established authors and writers are endless. TikTok will also be bringing new faces who are driving the #BookTok trend to Hay Festival.

A little bit of research led me to an article by Alicia Lansom from a few months ago explaining #BookTok on the online site Refinery29.

BookTok, according to the headline, is “the last wholesome place on the internet”.

If you were starting to think that social media was filled purely with angry people shouting at one another for no reason, you wouldn’t exactly be wrong. But thankfully, in the depths of TikTok, there is a wholesome place reigniting faith in the internet. The name of this magical world? BookTok. A sanctuary for literature lovers of all kinds, the #booktok tag currently has over 39.2 billion views as creators discuss their favourite reads through video reviews, recommendations and book nerd memes.

It’s now 53 billion views, by the way.

(Image: Westmont Public Library)

Given TikTok’s user profile, the books it talks about tend towards the young adult, with a bit of millennial interest thrown in. Part of the secret of its success seems to be that it doesn’t talk about books in the way that publishers do—or teachers or reviewers, come to that:

Taking in dystopian franchises, romance novels and period adventure series, the video trends include creators discussing plot points and character developments and even calling out authors for misrepresenting minority groups. A-level English it is not. And if you've ever struggled to know what to read next, BookTok's dramatically named reading lists vary from "books that had me sobbing at 3 am" to "books I would sell my soul to read again".

Another reason is that young people don’t necessarily know people in their own immediate friendship groups who like books, and so BookTok has created communities of interest. But it has also created communities of activists:

For other creators, BookTok has acted as a platform to call for progress in the literary world, a place where they are able to push for the inclusion and development of young queer characters. "I like to think that people follow me due to our shared goal of diversifying books," says 16-year-old Faye, who regularly creates LGBTQ+ content.

And for some creators, it has led—perhaps inevitably—to virtual book clubs.

"We Zoom every week, give each other advice and always support each other’s content. There honestly isn’t a single person I’ve interacted with in the TikTok book community who hasn’t been completely welcoming and friendly," (says British Booktokker Brittany, 21.) This level of friendship also extends to a culture of gifting. "A lot of us have our book wish lists in our bio and we often send books to each other," says 16-year-old British BookToker Kate.

All the same, there are still a few negatives. Lansom talks to one woman who has experienced Islamophobia, and says that reports of negative experiences have increased with the rapid growth in the app.

BookTok remains one of the best places to discover young female authors, according to Lansom. Writers are also joining the community to talk to readers—which the Hay Festival mentions in its sponsorship announcement. Her article comes with a handy guide on where to start if you’re curious:

there is a string of much-mentioned popular titles which you should probably get to know before heading in (including Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo, From Blood and Ash by Jennifer L. Armentrout and The Cruel Prince by Holly Black). If you pick only one fictional series to learn about ahead of time, A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas is probably your best bet. "I’ve never been surrounded by a series that’s been more analysed in the book community," says Ayman, adding that "the fandom can be very obsessive".

The US Publishers’ Weekly hosted a panel this month to discuss all of this from an industry perspective. A couple of observations from their panellists:

"There is no 'mainstream BookTok," but rather a collection of "niche communities," said (Shannon deVito of Barnes and Noble), citing a growing cadre of male sci-fi book reviewers on the app. (Booktokker Kendra) Keeter-Gray, whose account @kendra.reads has more than 123,000 followers, mainly reads romance and fantasy, and agreed that BookTok is surprisingly vast and diverse. "Every day I'm discovering new people with hundreds of thousands of followings," she said, "but who are in a totally different genre than me."

Sponsored content tends not to do well; organic engagement—following what’s happening, not trying to manufacture it—and being an authentic self tends to do better. You can’t “force” buzz.

But from a publishing point of view, backlist titles can do well when they get picked up by one of the communities of interest. And the interest starts on the app, but people looking to buy books come into stores:

What's happening on the app is not about staying on the app," (deVito) said. "It's about then going to the store, meeting people, building reading groups, and so on."..."We don't want to corporate-ify it," she said. "so we really lean on our booksellers." And it is those expert booksellers, she said, who "can be physical versions of the algorithm."

Oddly, quite a lot of this reminded me of the 1999 ‘Cluetrain Mainfesto’, which was a prescient article about how the web would change marketing.

Here are the first four of their ‘95 Theses’:

1. Markets are conversations.

2. Markets consist of human beings, not demographic sectors.

3. Conversations among human beings sound human. They are conducted in a human voice.

4. Whether delivering information, opinions, perspectives, dissenting arguments or humorous asides, the human voice is typically open, natural, uncontrived.

Given the way the web has turned out—“angry people shouting at one another for no reason”—it made me wonder what BookTok was doing right. I came to the conclusion that it was partly the way that TikTok works, and partly the calming nature of books.

And here’s an introduction on TikTok to #BookTok (double click on the image to play):

2: Seven types of stupidity

I am not a huge fan of Ian Leslie’s newsletter The Ruffian, and there’s probably not enough space here to explain why.1 On the other hand, every so often, he pulls out a piece that is absolutely terrific. (If you’re interested in Paul McCartney and the Beatles, for example, this post is long and fascinating).

And his recent post on Seven Types of Stupidity was definitely towards this end of the scale.

I might as well dive in with the seven categories:

- Pure stupidity

- Ignorant stupidity

- Fish out of water stupidity

- Rule-based stupidity

- Overthinking stupidity

- Emergent stupidity

- Ego-driven stupidity.

Some of these are pretty obvious—notably the first two—but the others are more subtle. Some of them overlap a little bit. I’m not going to discuss them all, but there are lots of worthwhile points in here.

Fish out of water stupidity, for example, while not that interesting of itself, is about the propensity of experts in one field to think their expertise extends beyond it:

They take their own accumulated knowledge for granted and believe that the facility it gives them in their field is merely a function of their all-round brilliance... Twitter has been great for revealing how scientists or historians can be stupid once outside of their academic field.

And sometimes their expertise is so narrow that they don’t notice that the domain has moved around them. In the 2008 crash, bankers thought they were dealing with risk, in which they regarded themselves as experts, but they were actually dealing with uncertainty.

Rules-based stupidity is about the idea that stupidity isn’t just a property of individuals (that belief might be regarded as a form of stupidity in itself) but of systems.

The Romans, for example, were stupid at mathematics, because their letter-based systems made it nigh impossible to do it. (Even arithmetic is pretty challenging). Adopting Arab numerals made this a lot simpler.

This observation is from the Santa Fe complexity theorist David Kracauer:

The tool or platform we’re using can keep us stupid, even when we’re smart. In fact, Krakauer’s view is that stupidity isn’t the absence of intelligence or knowledge; it’s the persistent application of faulty algorithms (itself an Arabic concept, of course).

Although the idea of algorithms makes us think of computers, a lot of our heuristics/ rules of thumb work in the same way as algorithms:

Look around and you can see people trapped in flawed algorithms (if there is war, then it must be America’s fault’; ‘if there is a market crash then a recovery is just around the corner’) Rules of thinking inflexibly applied lead to stupid conclusions.

Such rules of thinking lead to cognitive inflexibility—which itself can a form of stupidity.

The example about overthinking stupidity comes with a hilarious example. Researchers put some food at the left hand end of a T-shaped corridor (A) 60% of the time, and at the right hand end (B) 40% of the time.

(Source: The Ruffian)

Humans tried to work out a complex way of anticipating where the food would pop up next, and they were right 52% of the time.

A rat, meanwhile, just turned left every time, have worked out there was a better chance of finding food there, and so was right 60% of the time.

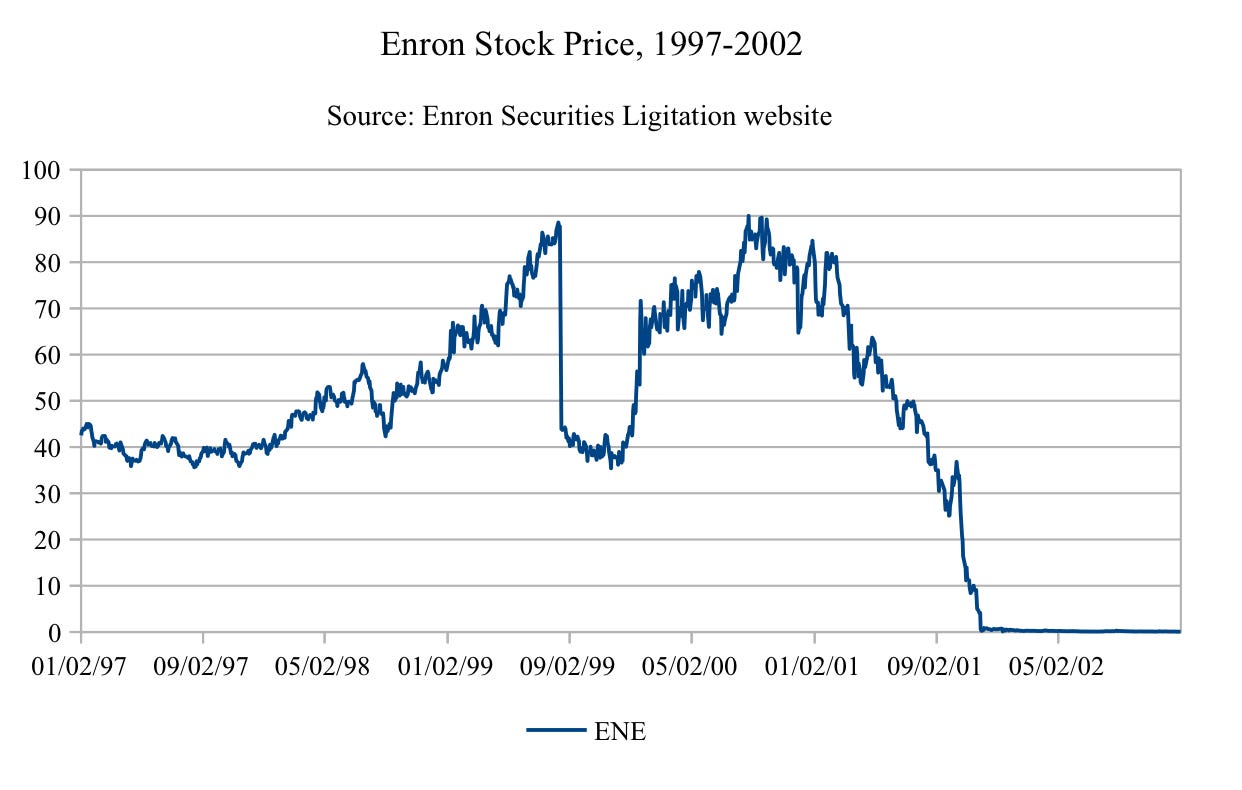

The category of emergent stupidity has something in common with rules-based stupidity. The system is full of smart people, but collectively they produce terrible outcomes. Enron, famously, was full of “the smartest people in the room”.

(The collapse of Enron. Chart by 0xF8E8, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

Collective intelligence can emerge when a group follows a few simple rules or guiding principles, but if the rules are badly designed, so can collective stupidity.

There is no innate human drive to avoid stupidity. We evolved to survive and thrive and that means getting along with others - that’s our priority, most of the time. The good news is that getting smarter and getting along are not necessarily at odds with one another; the bad news is that they often are... The more that members of a group follow a rule like ‘agree with the consensus’ or ‘agree with the leader’ the less gets contributed to the general pool of ideas and arguments. The shallower the pool, the more likely it is that something stupid will crawl out from it, covered in slime.

j2t#320

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Oh alright then: his writing often has a patina that expresses the privileges he enjoys of class, colour, gender, and place in the global distribution of income, and he seems blithely unaware of this.