26 September 2023. Social attitudes | Rhinos

Calling Ronald Inglehart, or the liberal shift in British social attitudes // Rewilding the white rhino [#500]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Just a small call-out to note that this is edition #500 of Just Two Things. I don’t think I expected to get that far. A rough calculation on my fingers suggests that there are probably around 800,000 words in the Just Two Things Substack archive, perhaps a bit more. My thanks to all the people whose articles I have quoted in that time.

1: The liberal shift in British social attitudes

The British Social Attitudes Survey has just published its 40th edition, which means that it is now able to compare data over four decades. Most of the coverage has focused on the general liberalisation of social attitudes. The Guardian’s report summarised it like this:

Examples of the ascendancy of liberal views include attitudes towards same-sex relationships – 50% of respondents said they were “always wrong” in 1983, compared with 9% in 2022 – and a woman’s right to choose an abortion, supported by 76% now, against 37% when the question was first asked 40 years ago. There have been similarly sweeping changes in public attitudes towards sex before marriage, having children outside wedlock, and traditional gender roles in the workplace and the home.

The survey is published in separate chapters by NatCen on its website, with chapter summaries and full pdfs. Although this is just British data, it seems at least possible that we would see similar patterns across Western Europe, partly because the social changes that seem to sit behind the changes in views are more widespread.

In the introduction, John Curtice summarises those changes like this:

Many more people now go to university, while fewer attend any kind of religious service. More are employed in white-collar jobs and fewer in blue-collar ones. More women, including those with younger children, go out to work, while a growing population of older people means there are more men and women who are no longer working at all. Immigration has ensured the country has become more ethnically diverse, while a decline in rates of marriage has been accompanied by more diverse types of family formation, including by same-sex couples whose partnerships are now legally recognised.

Social attitudes are clearly undergoing a long-term secular change. However, attitudes to government and spending are more cyclical. I’ll come back to that.

At the same time, one of the insights here is the time it takes for change to happen. Homosexuality was legalised in Britain in 1967, but sixteen years later, in 1983, in the first year of the BSA survey, only 17% thought that “same-sex relationships were not wrong at all”. This number declined in the following years.

As Elizabeth Clery notes in her commentary, there is

a dip in support in the early to mid- 1980s, with the onset of HIV-AIDS and the subsequent introduction of Section 28, and a marked rise in support around 2013, around the time of the introduction of the Same Sex Marriages Act. These blips are not evident in relation to support for pre-marital sex and suggest that, for some people at least, the legislative position and popular discussion in relation to homosexual relationships has the power to influence their views.

(British Social Attitudes survey 1983-2023).

In other words, the public climate matters.

For these reasons, I was interested by something that was a little buried in the report and ignored in the coverage that I saw.

Since 1986, NatCen has been asking a suite of questions that are designed to position the respondent on a ‘liberal/authoritarian’ scale, which

are designed to measure where people stand more broadly on the debate about the extent to which society should be requiring its members to follow a particular moral code and set of social norms, or whether individuals should be left to decide such issues for themselves.

Actually, having looked at the actual questions in the Technical Report, I’m not sure that this is quite what they measure. Here’s the questions:

(NatCen British Social Attitudes, 2023, Technical Report.)

Here’s the headline chart on that for the whole population:

(British Social Attitudes survey 1986-2023).

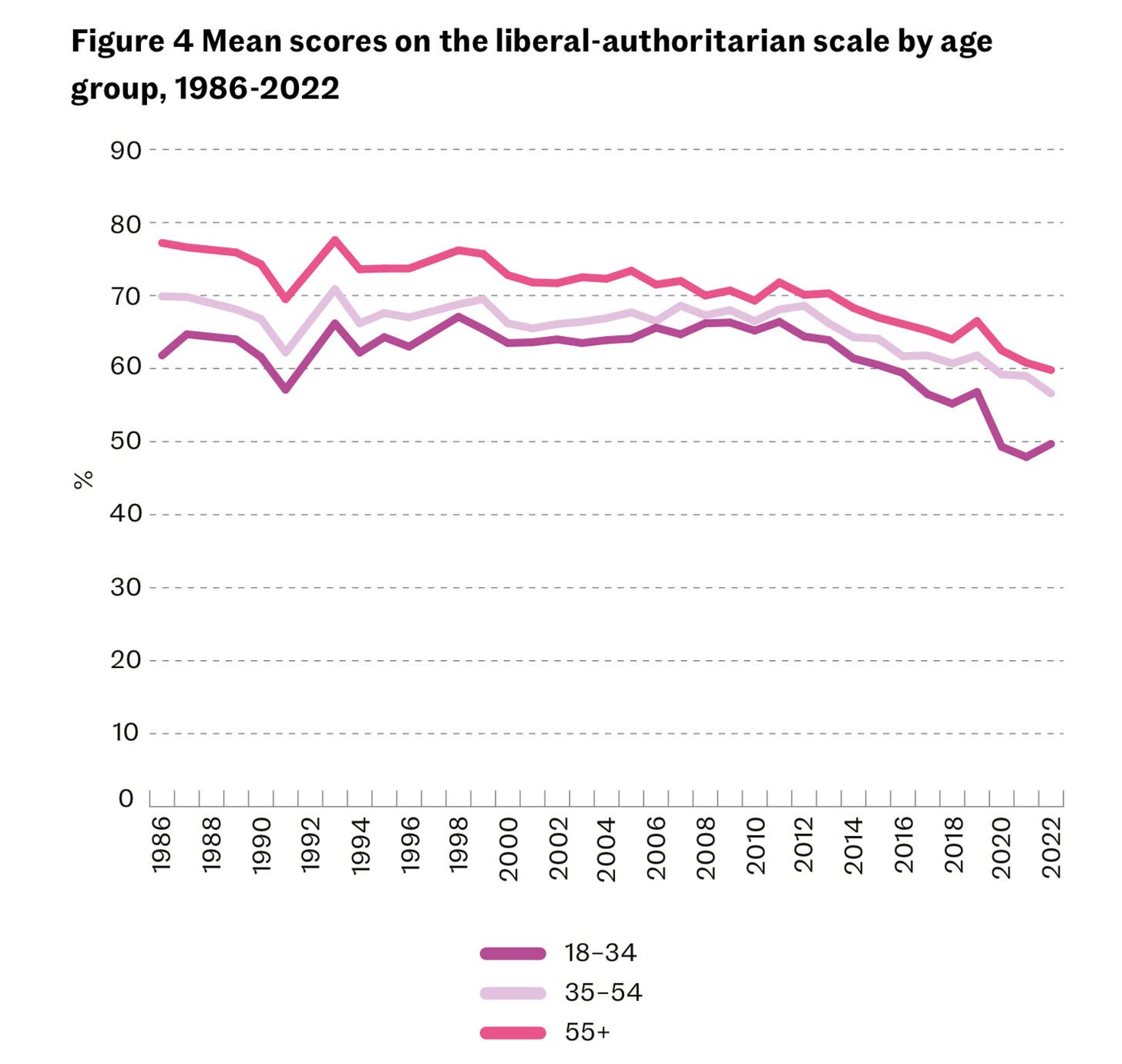

They fluctuate for much of that time, and then show a marked shift about a decade ago. There are age differences within this, of course, which are covered in the chapter on generational differences.1 Here’s the chart:

(British Social Attitudes survey 1986-2023).

Younger people, in other words, have always been more liberal on this spectrum compared to both middle-aged and older people. But older people are now more liberal than younger people were for the first 25 years of the survey.

So this might be regarded as proof of Ronald Inglehart’s post-materialism thesis, in which he argued that post-materialist values, around self-expression, autonomy, diversity, and so on, would replace ‘modern’ values, characterised by conformity and authority. (This is the distinction that underpins this scale, and this makes sense since Inglehart’s book was published in 1977, so his ideas were percolating into social research in the mid-80s.)

But, but: Inglehart’s model was based on a Maslovian idea that as people got more affluent they would become more post-materialist because they could afford to be. And this change in values seems to coincide with a period when British living standards were flatlining. So it is possible that this is a secular shift that is completely disconnected from economics.

And young people are now less keen on increased taxation and public spending than old people, which has reversed over 20 years:

In 1984, 42% of those aged 18-34 supported increased taxation and public spending, compared with 33% of those aged 55 and over.

Although by 1995, support among younger people for more taxation and spending had increased to 55%, among older people it had risen to 60%.

Now just 43% of younger people favour higher taxation and spending, whereas as many as 67% of older people express that view.

In commentary, NatCen observes that this might just be a function of who pays tax and who receives benefits from the government, since in the UK older people are definitely state beneficiaries through things like the “triple lock” on pensions, while younger people are not. For example, they now pay fees to go to university, which they didn’t do in 1984.

Finally, although in general opinion on sexual matters has liberalised hugely over the last 40 years, the last few years has seen a shift in attitudes towards transgender people.

64% describe themselves as not prejudiced at all against people who are transgender, a decline of 18 percentage points since 2019 (82%).

It’s worth noting that 64% is still a high number. All the same, I’ll say it again: the public climate matters.

2: Rewilding the white rhino

My feed suddenly had quite a lot about rhinos in it, and I realised that this was because it was World Rhino Day last Friday and the International Rhino Foundation had published its annual State of the Rhino report.

Of course, the rhino is still an endangered species, still poached for its horn, but there were straws in the report that suggested that for some rhino species the tide might be turning. Here’s the report’s infographic:

(Source: International Rhino Foundation)

In 2022, the world rhino population increased by 5%, and the reason seems to better conservation measures. Although more than 550 rhinos were killed by poachers last year, one report—which I can’t find again now—said that the proportion killed by poachers had fallen to below 3.5%, which is a threshold level that enables the populations to grow.

Overall, the rhino population increased to 27,000, which is a step in the right direction, but still a long way below the population size of 50,000 in the 20th century. The numbers of the Black rhino—one of the three critically endangered rhino species—have also increased, to almost 6,500 animals.

The other two critically endangered Rhino species — Javan and Sumatran — are still numbered in the tens. The official count is 76 Javan rhinos and an estimate of around 50 Sumatran rhinos, but both of these may be over-estimates.

(Photo of White rhinos: Savetherhino.org)

There’s also been an increase in the population of the White rhino population for the first time in a decade (despite the headline on the infographic). And the white rhino seems to be a story that summarises the battle between conservation and poaching. There were fewer than 100 White rhinos in the world in the early 1900s, and 3,500 fifty years ago, but the population had been helped to recover to more than 21,000 by the end of 2012.

This meant that they became the most attractive target for poachers, since they represented the largest population of rhinos, and over the last 10 years they have declined to around 16,000. The population is now more dispersed, which makes it harder for governments to protect them, but also makes it harder for poachers to find them.

The other reason that poachers track White rhinos is because despite their size they are fairly docile creatures—they could do with some of the aggression that hippos display.

But buried in the report is a story that also suggests the shape of conservation to come:

the sale of Platinum Rhino Project and their 2,000 southern white rhinos to nonprofit African Parks, which will begin historic and critical translocations across Africa in order to build rhino populations in key protected areas. After years of uncertainty about the fate of these animals, which comprise an eighth of the world’s white rhino population, this plan... will greatly contribute to conservation of the species.

At The Conversation, the ecologist Jason Gilchrist has a bit of background to what this is all about.

The Platinum Rhino Project was a private venture to farm rhinos, run by the South African businessman John Hume, in the hope that a legal international trade in rhino horn might be permitted. There had been an (unlikely) argument that such a trade might reduce poaching:

The logic here is that legalisation would flood the market with legal rhino horn, devaluing illegal horns and slashing the profits of poachers and wildlife traffickers. With that, the incentive to kill rhino would shrink.

Anyway, it didn’t happen, despite lobbying by Hume (there’s chirpy five-minute PR video on youtube), so he put the farm up for auction. But with no legal market for rhino there weren’t any buyers, and so the non-profit African Parks was able to acquire the herd instead. They manage 20 million hectares across 22 national parks and protected areas in 12 countries.

They have a track record in this area: The charity has already reintroduced rhino to parks in Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo and Malawi.

They now plan

to translocate the rhino to well-managed protected areas across Africa, to supplement or create strategic populations to protect the long-term future of the species.

Gilchrist was involved, a few years ago, in what was then the largest rhino translocation, involving 30 rhinos to Rwanda. (There’s a 10-minute video at the bottom of the piece if you want to know more, or just watch some rhinos.) African Parks plans to distribute the 2,000-strong Platinum Rhino herd in ten years. It’s a huge undertaking.

But it makes sense. As Gilchrist says:

As an ecologist, I don’t see the point in conserving a wild species to keep in captivity. Wildlife belongs in the wild.

There’s a bigger point here. Rhinos are, in the wild, important parts of their ecosystem. Restoring them to the wild is complex, but it helps to remake ecologies, and support local economies. As the IUCN said in a news release:

They create habitats for other species, providing opportunities for future global restoration and rewilding options. Thriving wild African rhinos can also contribute to the livelihoods and well-being of local people, attracting tourists from all over the world, creating employment opportunities and contributing to economic development.

Gilchrist quotes a recent paper that says that rewilding, or restoring ‘megafauna’, as large animals are known, is complex, but requires a shift from farming to ‘wildlife ranching.’ It seems likely that the African Parks translocation of its 2,000 rhinos to new parts of Africa will function as a whole set of pilot in understanding what we need to do to make this work.

j2t#500

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

There are also marked generational differences in the UK about left-right politics, but the libertarian/authoritarian scale doesn’t translate directly. There’s a different scale for left-right attitudes. The chapter on generational differences discusses this.

I just went back to look at the chapter, and it doesn’t seem to have considered whether this is different in Scotland, which for my money would have been a good way to test the hypothesis. Disappointingly, the discussion about left/right attitudes refers exclusively to Conservative and Labour voters, which suggests a focus on the (large) English samples. It’s also worth noting (Figure 7 in the generational divide chapter) that the cyclical effects on views on tax and spend are quite strong—about a decade for upswing and downswing—and that different generations do track each other. We’re definitely on an upswing at the moment.

I know that NatCen has a big sample and do research the whole of the UK. The example of tuition fees was just an example: generally public spending has been loaded against the young over the past decade and a half: you have the Triple Lock, but you close down the SureStart programme or other childcare support, for example. But I agree that there might be differences in these generational views in Scotland and Wales.