26 May 2023. Technology | Change

The limits of technology innovation // Thinking like the 21st century.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

It’s a public holiday in Britain on Monday so the next Just Two Things will be out next Wednesday.

1: The limits of technology innovation

Rodney Brooks is one of the more interesting technologists in the world, straddling business and academia, and the worlds of digital and manufacturing. He also has a strong grasp of the conditions under which technologies finally arrive in the mainstream. So a long interview with him in IEEE Spectrum is something to be welcomed.

The interview starts with AI—I guess it has to at the moment, at least editorially speaking—but the more interesting parts are why self-driving cars have stalled and about his current robotics start-up, working on robotics in warehouses.

But let’s get the AI bit out of the way first. The problem he sees here is that people look at AI, and mistake performance for competence. The way he describes it (although he doesn’t put it exactly like this) is that effectively we’re anthropomorphising AIs by ascribing characteristics in them that we’d ascribe to people who showed the same level of performance:

When we see a person with some level performance at some intellectual thing, like describing what’s in a picture, for instance, from that performance, we can generalize about their competence in the area they’re talking about. And we’re really good at that. Evolutionarily, it’s something that we ought to be able to do. We see a person do something, and we know what else they can do, and we can make a judgement quickly. But our models for generalizing from a performance to a competence don’t apply to AI systems.

(Playing frisbee in the park. Photo by Don DeBold/flickr, CC BY 2.0)

We can’t make the same assessment of an AI because the AI doesn’t have a model of the world which allows it to broaden its understanding from the particular to the contextual. (Again, I wrote about this here recently). He uses the example of watching a person throwing a Frisbee:

if a person says, “Oh, that’s a person playing Frisbee in the park,” you would assume you could ask him a question, like, “Can you eat a Frisbee?” And they would know, of course not; it’s made of plastic... Or, how far can a person throw a Frisbee? “Can they throw it 10 miles? Can they only throw it 10 centimeters?” You’d expect all that competence from that one piece of performance: a person saying, “That’s a picture of people playing Frisbee in the park.”

He’s been using AI to help with coding, and he has a couple of observations. The first is that when it’s good, it’s much better than a search engine, because it gives more context. But it is also very confident when it makes mistakes (I believe that ‘hallucinating’ is the tech euphemism for this). This is because it is a language correlation machine.

He doubts if AI is going to have the adverse effects on categories of employment that are often proposed—and the discussion of robotics, below, is relevant here. He’s also sceptical that AI is going to wash its face financially (I realise that this has been a bit of a theme here recently). In general, he thinks AI is going to be “another thing that’s useful”:

(J)ust to articulate where I think the large language models come in: I think they’re going to be better than the Watson Jeopardy! program, which IBM said, “It’s going to solve medicine.” Didn’t at all. It was a total flop. I think it’s going to be better than that. But not AGI.

On AI, by the way, he recommends Stephen Wolfram’s long essay on the subject.

He’s also clear-eyed on how long change takes, and self-driving cars are a good lens for that. Because it’s less than a decade since CEOs of car companies were predicting that self-driving cars would be everywhere by now. And where we actually are is that Level 2 and 3 work pretty well, but Level 5—full self-driving—is still a series of demonstrator projects in a small number of American cities. This is also an area where there are huge levels of spend that may be hard to get a return on.

(The future of the automated highway, 1961, via computerhistory.org. Image: Popular Mechanics)

But one of the problems of this kind of reckless techno-optimism is that it shuts down forms of innovation that are more likely to work. For example, he points to the research in the 1990s into using guide sensors in the roadway to enable forms of vehicle automation. The infrastructure would enable the cars to guide themselves:

(T)hen the hype came: “Oh no, we don’t even need that. It’s just going to be a few years and the cars will drive themselves. You don’t need to change infrastructure.” So we stopped changing infrastructure. And I think that slowed the whole autonomous vehicles for commuting down by at least 10, maybe 20 years.

He has a bigger point here. As a species, we’ve done several big mobility upgrades over the past several centuries, and they have all required investment in infrastructure. So there’s a certain hubris—my reading of what he’s saying—if you announce that this time it is going to be different:

When you go from trains that are driven by a person to self-driving trains, such as we see in airports and a few out there, there’s a whole change in infrastructure so that you can’t possibly have a person walking on the tracks. We’ve tried to make this transition (to self-driving cars) without changing infrastructure. You always need to change infrastructure if you’re going to do a major change.

Brooks’ current start-up is a company that’s doing robotics in the warehouse. Because Amazon has huge warehouses and has invested heavily in this technology, people have an expectation that warehouses will become automated. Amazon has designed its warehouses around robot workflows (which is probably one of the reasons why they are such horrible places to work). (He had a previous robotics start-up that was “a beautiful artistic success, a financial failure” because it was in the market too early.) But most warehouses—80% of them—are much smaller, and currently have “zero automation”:

We start with the assumption that there are going to be people in the warehouses that we’re in. There’s going to be people for a long time. It’s not going to be lights-out, full automation because those 80 percent of warehouses are not going to rebuild the whole thing and put millions of dollars of equipment in. They’ll be gradually putting stuff in. So we’re trying to make our robots human-centered, we call it.

One of the secrets to that is that the robots need to treat their human co-workers with respect (this reminded me of Michael Frayn’s comic 1960s novel Tin Men about an automation research institute trying to train robots in philosophy). The other is to design them so humans can take control of them easily:

(T)he magic of our robot is that it looks like a shopping cart. It’s got handlebars on it. If a person goes up and grabs it, it’s now a powered shopping cart or powered cart that they can move around. So (the warehouse workers) are not subject to the whims of the automation. They get to take over.

All of this reminded me that a lot of the technological determinism we’ve seen in the digital technology surge has been because so much of the technology has been relatively self-contained. Even aspects of it that needed new infrastructure—like mobile telephony—needed fairly self-contained infrastructure. Generally it was able to deploy within existing systems. Most technology innovation is more complex—and a lot harder to do.

(Thanks to John Naughton’s Memex 1.1. Blog for the link).

2: Thinking like the 21st century

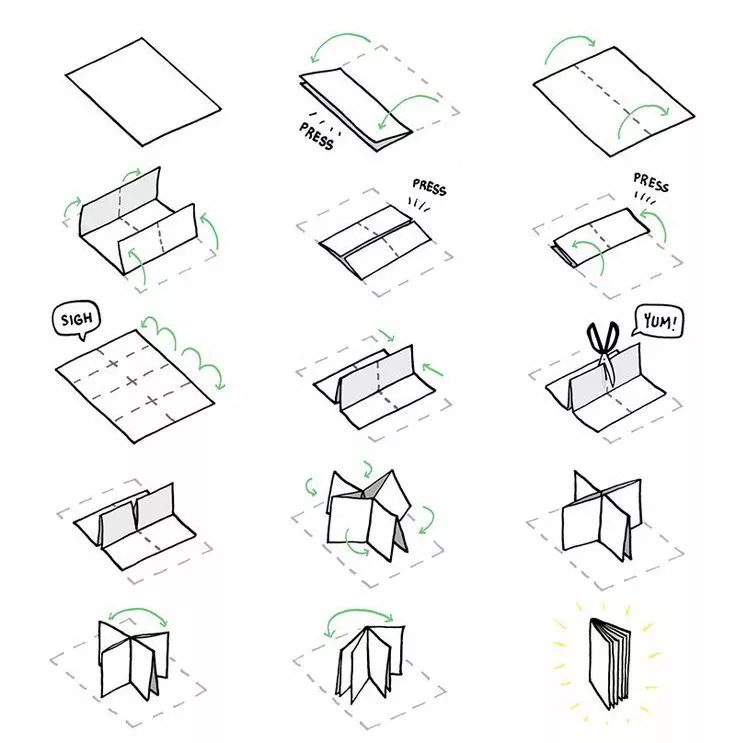

Obviously I know how to have a good time, so when I saw that Doughnut Economics had designed a little booklet that summarised its seven principles of change—“How to think like a 21st century economist”—that you needed to print and then cleverly fold, I obviously gave it a try. (You need a pair of scissors as well).

But this was definitely a successful project, as the photo demonstrates.

(Image: Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

But more to the point, it is also a helpful guide to seven principles of change, so I’m just going to list them here, with some brief commentary.

1. Change the goal

This is the ‘doughnut’—we need to organise our economic activity so that it sits between a sustainable social base and the planetary boundaries. But it’s also a reminder of Donella Meadows’ list of ‘leverage points’; changing the goals of the system is one of the strongest levergae points on the list.

2. See the big economic picture

The economy is embedded in society, and society is embedded within the overall environment. Markets are only one part of the economy: households, the state and the commons are all in there too.

3. Nurture human nature

This is about the importance of caring, reciprocating, communities in making life work. This is usually listed under the heading of ‘social capital’, but I think it’s also possible to think of it as a form of ‘human commons’. Either way, the idea that ‘care’ is going to be a necessary part of the new economic structure of cities is something I have written about here.

4. Get savvy with systems

“Embracing the unpredictability of complex systems and their interconnections” is the comment in the booklet, and — from my perspective this links again to Donella Meadows and her observation that if you are trying to make change happen quickly you need to identify the positive and negative feedback loops, amplify the former, and damp down the latter.

5. Be distributive by design

“Sharing opportunity and value with all who co-create it”—which means everybody in society. And again, we know from the work of Wilkinson and Pickett that societies that do this are better for everyone, not just better for the poor.

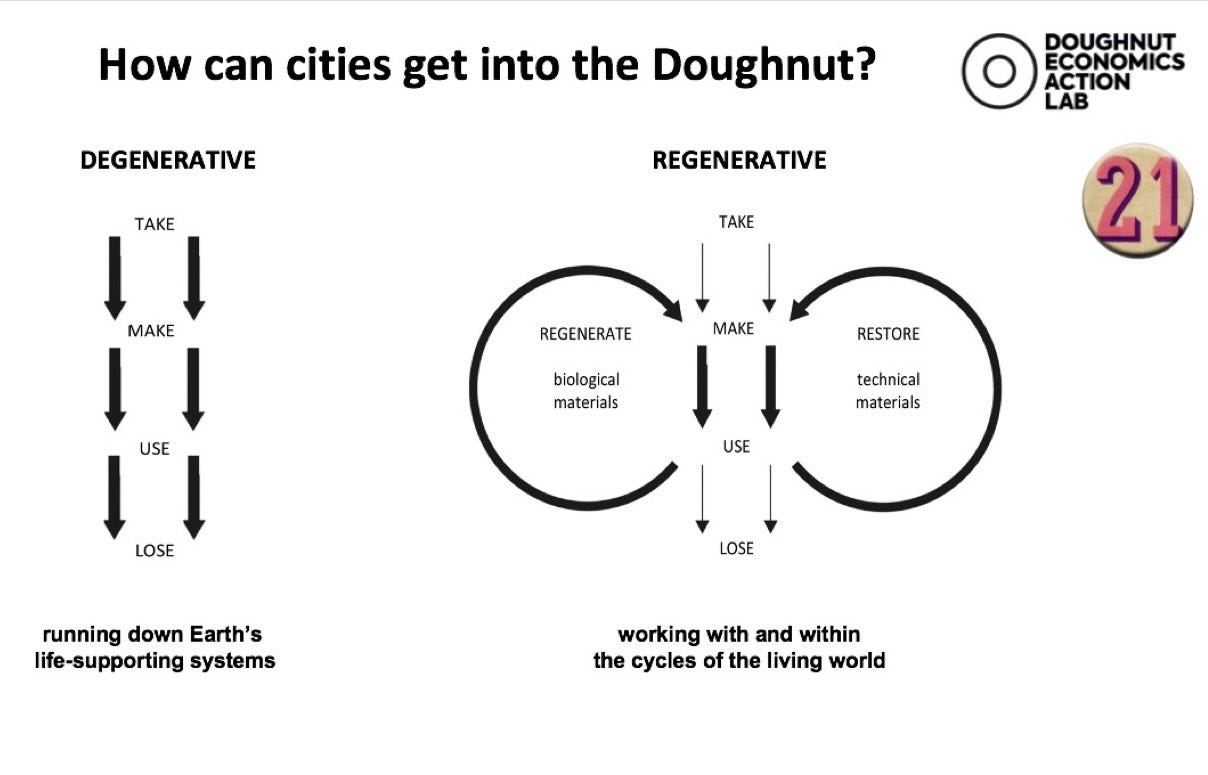

6. Be regenerative by design

There’s a nice little diagram in the booklet that has a loop on the left that says ‘regenerate biological materials’ on the left, and one on the right that says ‘restore technical materials’, and contrasts this with the dominant current market model of “Take-Make-Use-Lose”. In fact, it’s a simplified version of this diagram.

(Image: Doughnut Economics Action Lab)

7. Think again about growth

The copy here says,

“We need economies that help us to thrive, whether or not they grow.”

And this reminds that I’ve noticed non-21st century economists getting more strident about the horrors of the ‘degrowth’ movement, in a way that suggests that the idea of ‘degrowth’ might be heading towards the mainstream.

Of course, one of the problems of criticising the idea of ‘degrowth’ is that we might not have a choice about it, when you look at the Limits to Growth data. The choice might be whether we get managed degrowth, or unmanaged degrowth—and unmanaged degrowth would be a lot worse.

And the other issue here is that ‘growth’ is tied up with GDP, which everyone agrees is a very limited indicator, even a problematic one. Some of the trends we’re seeing at the moment, such as the four-day week, suggest to me that people understand that there are other things to value in life than money (which is what GDP is very good at measuring). But there’s a longer post here that needs quite a lot more thought.

(Leaflet folding instructions. Source: Doughnut Economics Action Lab)

Update: Business

I mentioned the work of Brett Christophers here recently in a piece on how infrastructure companies had become financial vehicles, and he popped up in The Guardian this week on the way in which the “alternative asset managers” such as private equity companies claim that they are rewarded for takings risks—but actually are largely shielded from risk. Here’s an extract:

(T)he business of alternative asset management is less about taking on risk than, in (Jacob) Hacker’s terms, moving it elsewhere. So when things go wrong, others bear the brunt. This can be the employees on the shopfloor of a retailer owned by private equity who find that they’ve shouldered the risk when they’re told they’re being laid off. It can be ordinary retirement savers, who find they have a meagre pension because the alternative funds in which their savings were invested by the asset manager have tanked. Why does this matter? Because unless elected policymakers understand how risk is produced and distributed in modern economies, they will not be in a position to act appropriately and proportionately.

j2t#460

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.