15 May 2023. Change | Lawyers

We need to change our deep narratives if we’re going to make change happen. // Holding law firms accountable for their fossil fuel work.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: All civilisations have a deep narrative story

This is the the first part of a two part review of John Higgs’ book, ‘The Future Starts Here’. The second part will be on Wednesday.

I ordered John Higgs’ 2019 book The Future Starts Here from the library because I wanted to see how he addressed the subject of “the future.” Higgs is an idiosyncratic writer who tends to write expansive if English cultural histories: William Blake, The Beatles and James Bond, Watling Street, the KLF.

(Image: John Higgs)

His starting point here is a cultural one: how is it that in the space of a few decades we have gone from optimistic views of the future to pessimistic ones—from the 1939 World’s Fair to Mad Max and The Road. His subtitle is: ”An Optimistic Guide to What Comes Next”.

When the post-apocalyptic Australian film Mad Max 2 was produced in 1981, it was necessary to explain to the audience why civilisation had collapsed. Text at the start of the film explained how, in the near future, the world would run out of oil and this would lead to the dystopia depicted in the story that followed. Now, it is no longer necessary for writers and filmmakers to explain the post-collapse worlds they explore (p2).

There’s also a generational question here as well:

When I was growing up in the 1970s, the idea that society was progressing, and that life would get better, was still a part of mainstream culture... The idea of constant progress and improvement had been the dominant Western narrative for centuries, embedded in everything from the Age of Enlightenment to the American Dream. When the Sex Pistols emerged like harbingers of an unwelcome nightmare and announced that we had 'no future', that was really shocking.

In developing this idea he has chapters that seek to understand AI, virtual reality, augmented reality, social media, space exploration, and some other things that crop up along the way. I’m not going to spend much time on those here, because they cover familiar ground, albeit in an interesting way.

But I should add a note to any reader who thinks that a discussion of AI from 2019 is going to have been overtaken, because Chat GPT: you would be wrong. Because Higgs is largely a cultural analyst he is interested in what lies beneath the surface of things. And so his discussion of AI spends quite a lot of time on notions of both intelligence and consciousness. This proceeds through Descartes and the consciousness of octopi, but a section in which he talks to Alexa about his cat is also emblematic of his style:

'Alexa, are you more intelligent than my cat?' I ask. 'Sorry, I can't find the answer to the question I heard,' she says. The cat shakes his head in a pitying manner...

'Alexa, does intelligence require awareness? I ask. 'Sorry, I didn't understand the question I heard, she replies. Awareness is an intrinsic part of cat, and human, intelligence. Alexa has access to potentially unlimited information, but data is a different thing to knowledge or understanding. (pp50-51)

The reason I’m not spending much time on these is because Higgs has a much bigger story here that he is trying to understand.

His underlying idea is that all civilisations have a “circumambient mythos”, or a deep narrative structure, that defines how they see the world. (Lyotard calls this a grand narratif). He thinks that our existing mythos has run its course, and that part of the confusion of the current moment is that we are in the middle of creating a new one.

The word 'circumambient' suggests something that entirely surrounds us, but also permeates everything so completely that we almost don't notice its presence. The importance of the circumambient mythos is why I was talking about mainstream Hollywood movies... It is in the bigger picture that the wider concerns of our culture reveal themselves (p9).

Because a circumambient mythos is a narrative, it falls into a narrative patttern. Higgs draws here on the work of Christopher Booker, who argued that there were seven types of plot. These are:

Overcoming The Monster, Rags to Riches, The Quest, Voyage and Return Comedy, Tragedy, and Rebirth (p10).

There’s a bit of a shoe shuffle here, since Higgs suggests that all circumambient mythos must fall into one of these seven story types , and there are other versions of this list of basic narratives. But it’s not a crazy step to take, so let’s go with it.

His view of our narrative history here is that pre-industrial revolution Christian societies (we’re looking at this through a Global North/western lens) were basically in a Voyage narrative. The Enlightenment substituted a Quest narrative instead: “We were on a journey to a better place, provided we could overcome all the obstacles that the journey tests us with” (p11).

But as we get to the limits of that Enlightenment story (see my previous writings here on modernity and its limits) this has become a Tragedy. I like this: Tragedy happens when the character flaws of the protagonist combine to destroy him or her.

Booker’s account of Tragedy runs like this:

'For a time, as the hero embarks on a course, he enjoys almost unbelievable, dreamlike success’, he continued. 'But somehow it is in the nature of the course he is pursuing that he cannot achieve satisfaction. His mood is increasingly chequered by a sense of frustration... The original dream has soured into a nightmare and everything is going more and more wrong. This eventually culminates in the hero's violent destruction.'

This is, Higgs suggests, the narrative we’re all living in at the moment. But his conceit here—hence the “optimistic guide” in the book’s tagline—is that we might be able to transform this into a mythos that is formed by Comedy, not Tragedy. As a narrative form, Comedy is not about jokes or slapstick. It is about a character flaw that doesn’t prove fatal, but can instead be resolved.

After a long diversion through a whole range of technologies, the potential mechanism for this change eventually reveals itself. It is generational change, or more precisely, generational change informed by fluent access to social media and digital networks.

This insight comes from an unlikely source: watching John Hughes’ 1980s film The Breakfast Club with his teenaged children.

More on that on Wednesday.

2: Holding law firms accountable for their fossil fuel work

Law Students for Climate Accountability (LSCA) is a law student-ledmovement that is trying “to push the legal industry to phase out fossil fuel representation and to support a just, livable future.”

Last year they wrote a “law firm climate change scorecard” on the US law firms. Now they have written a report on what they call “The Carbon Circle”—a play on the notion of London’s blue riband “Magic Circle law firms.” The subtitle is: “The UK Legal Industry’s Ties to Fossil Fuel Companies.”

Specifically, the report looks at two areas of legal activity. The first is where firms are involved “in transactions involving oil, gas, and coal projects”. The second is about “arbitration cases where law firms have represented fossil fuel interests against national governments.”

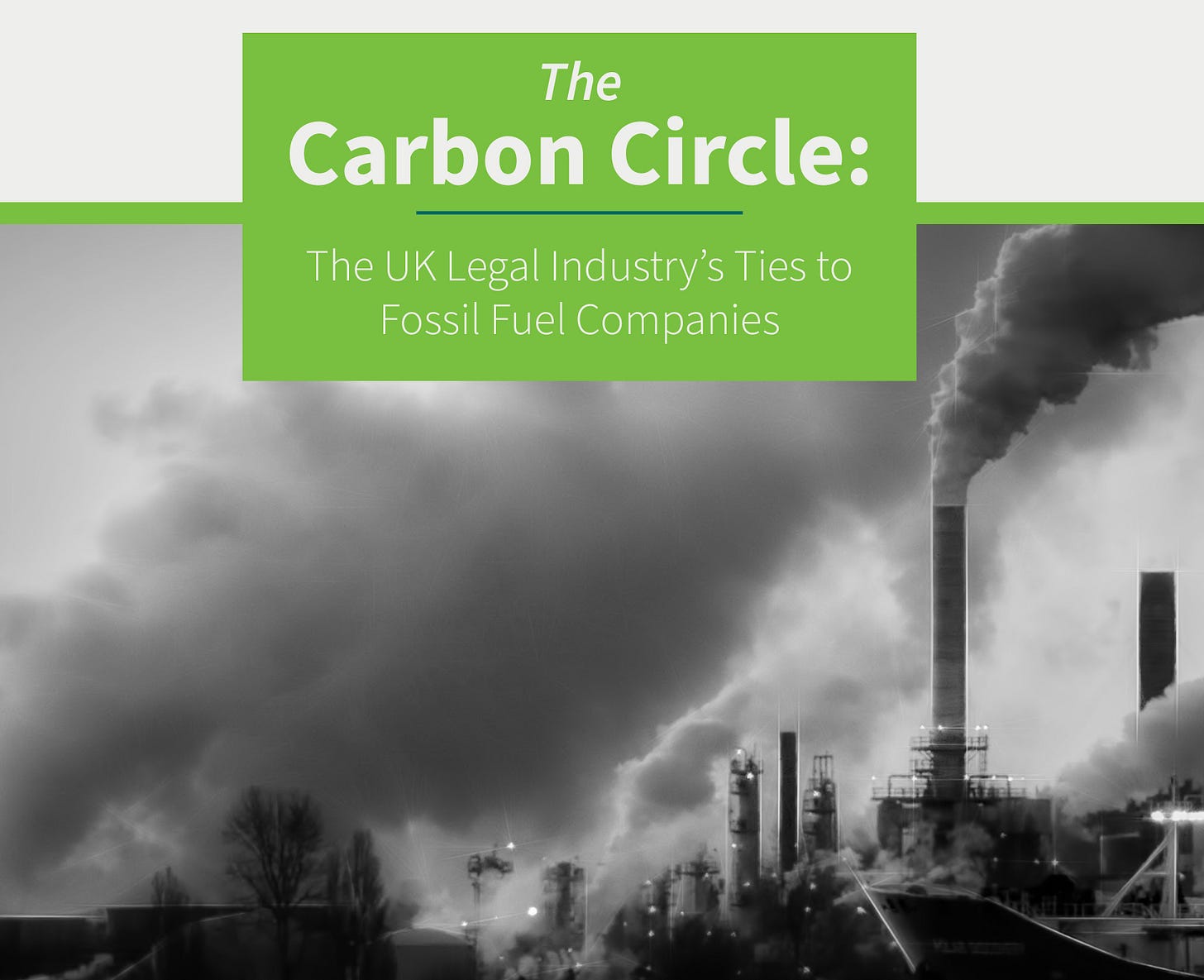

And frankly, these are big numbers. From the executive summary to the report:

In the context of transactional work (e.g. drafting contracts and arranging financing), from 2018 to 2022, 55 firms facilitated £1.48 trillion in fossil fuel projects, more than 2.5 times the amount these firms facilitated for the renewable energy industry (£546 billion).

They looked at these 55 firms because they each did more than a billion pounds sterling in fossil fuel transactions in the five years from 2018 to 2022.

Within this group, the five “Magic Circle” firms (Clifford Chance, Allen and Overy, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Linklaters and Slaughter and May) did “£285 billion worth of fossil fuel transactional work”, or almost 20% of the total fossil fuel transactions.

(Source: LSCA, ‘The Carbon Circle’)

In the second category—of arbitration cases—two firms are involved in more than 20% of cases:

Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and King & Spalding represented fossil fuel interests in more than 20% of all fossil fuel-related cases examined in this study... These two firms play a disproportionate role in ensuring fossil fuel interests prevail in arbitration disputes, representing more than ten times the average number of cases across the 55 firms examined in the report.

Freshfields is slightly out in front, with 20 cases, King & Spalding were involved in 18 cases.

(Source: LSCA, ‘The Carbon Circle’)

As the report notes, more generally:

Fossil fuel companies do not act alone. Law firms play a substantial role in facilitating fossil fuel development. Behind every fossil fuel project, there is a lawyer representing the interests of a fossil fuel company. Specifically, London-based law firms attract a large proportion of international commercial activity and provide key legal services for the fossil fuel industry.

The report was written by a group of researchers at a range of British and Irish universities.

This whole area—of what might be called the “carbon responsibility” of lawyers and the legal profession—has been moving quite fast recently. In March, as the report notes,

a group of lawyers and advocates orchestrated a climate action at the Royal Courts of Justice in London. Lawyers are Responsible issued a ‘declaration of conscience’, sending a clear message that they projected directly onto the building that houses the Royal Courts: an urgent and radical transformation is needed to seriously tackle the climate crisis.

In April, Lawyers for 1.5 degrees issued an open letter calling on lawyers to engage in more climate-conscious practice. This caused some controversy among barristers—who, at least in theory, have to follow a ‘cab-rank’ rule that means they can’t pick and choose who they represent—but is less problematic for solicitors, who can choose their work.

And in April, the Law Society, which represents solicitors, issued guidance to solicitors on climate change work:

Climate-related issues may be valid considerations in determining whether to act. Some law firms are evaluating risks to their commitments in this area and some are placing limitations on the instructions they will accept citing their own organisation's climate change commitments.

For lawyers, the most significant GHG emissions associated with your organisation are likely to be emissions associated with the matters upon which they advise, rather than scope one-to-three emissions...

Some solicitors may also choose to decline to advise on matters that are incompatible with the 1.5°C goal, or for clients actively working against that goal if it conflicts with your values or your firm’s stated objectives.

(My emphasis).

Of course, the companies that make billions from the fossil fuel sector also talk a good greenwashing game on climate change The report runs through of these, and they obviously represent a vast disconnect between what they say and the effects of their work. Clifford Chance, for example:

Managing our footprint not only contributes to a more sustainable world, it motivates our clients and our people. We target net zero ambitions at the same time as helping our clients with theirs. We are also aligning our community work and resources with environment-focused initiatives and climate change solutions.

Well, you’ll have got the drift by now. It’s interesting to me that this work is being driven by law students, because recruitment and retention is one of the biggest levers to get business behaviour to change, and the report comes with a handy set of questions for applicants and law firm associates to ask on the subject of climate change.

What this reminded me of was Oliver Bullough’s argument that elite London professional services firms had become the butlers to the world’s oligarchs, which I wrote about here. But it turns out that they’ll service anyone who has enough money. Just as long as it pays the salaries and profit-shares of the Magic Circle partners, which run at between £1.5–£2m a year, who cares about about ethics, or the planet?

UPDATE: AI

I wondered here a few weeks ago what kind of business the AI business might be. Because I am sceptical that there’s enough money in it to sustain the future scale that people talk about.

And I see that the blogger Dave Karpf has been reflecting on this recently as well. Here’s an extract from this post:

Where I think this will be most transformative is in online productive tools. We are probably approaching a future where Microsoft unveils a legitimately awesome next-generation Clippy… My other, more dystopian instinct is that there simply isn’t going to be enough money in online productivity tools to justify all the money that has been invested in building the AI future. OpenAI burned through $540 million developing ChatGPT last year. Sam Altman has suggested they’ll need $100 billion to develop the AI of his dreams. There is not $100 billion+ of revenues to be found in Clippy-but-awesome…

Over time, the trajectory of every new technology bends toward money. There are reasons to be excited about the ways this new technology might simplify our lives. It’s going to make satisficing so much easier, and that is often just what we need. But we should also watch the emerging revenue models closely.

(Thanks to John Naughton for the link).

j2t#455

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.