25 March 2022. Stonehenge | Design

Understanding Stonehenge. The rise and fall of ‘Corporate Memphis’

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Understanding Stonehenge

Exiting through the gift shop of the current British Museum exhibition about Stonehenge, I picked up Rosemary Hill’s book of the same name. It’s a cultural history of Stonehenge which tracks the way we have understood the stones over time.

I’ll come back to that, but first, the exhibition. It locates Stonehenge in the culture of its time across northern Europe, and it’s impossible not to be impressed by the quality of the craft, given the tools they were working with. The exhibition also covers the other ‘henge’ monuments, such as Woodhenge and Seahenge. It’s also striking how much people travelled. Stonehenge was visited by people from all over northern Europe. Trade was also extensive – this piece, found in Germany, which marks the positions of the rising and setting sun at different times of the year, was made with gold from Cornwall and bronze from central Europe.

(The Nebra Sky Disc, in the British Museum’s Stonehenge exhibition. Photo, Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC 4.0)

The layout of the exhibition is a little annoying – crowded near the door, much more space further in. It’s also sponsored by BP, which is more than annoying.

I hadn’t realised how long it took to build the various elements of the site. Stonehenge emerged over 70 generations, or 1500 years. I can’t think of something physical in our contemporary culture that has been relevant for that length of time.

In her book, which is short and crisply written, Rosemary Hill divides her material chronologically. As it turns out this also works thematically.

The first wave of Stonehenge researchers were antiquarians – in some ways forerunners of archaeologists – who were interested in understanding the past through objects rather than through documents. John Aubrey, best known as a biographer, was among the first to study the stones, to identify Avebury as a stone circle, and to float the idea of ‘druids’. He gave a paper about Stonehenge to the Royal Society.

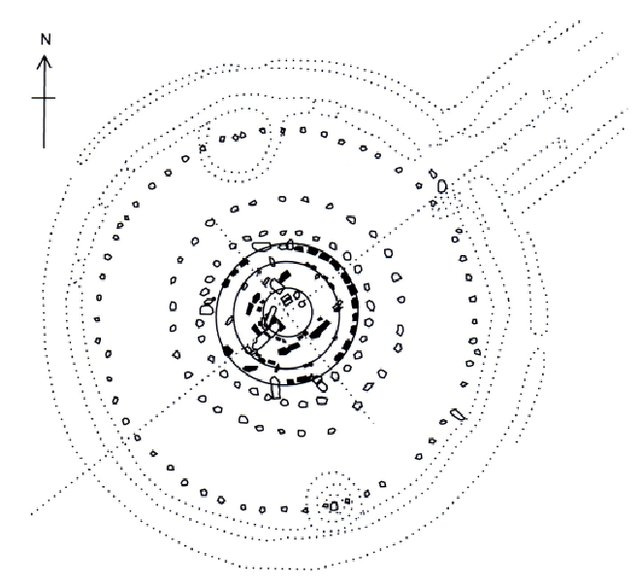

William Stukely, who published his book Stonehenge in 1740, built on Aubrey’s work. He visited Stonehenge and Avebury repeatedly, connected Stonehenge with the wider landscape, excavated some of the nearby barrows, and was the first to measure the place properly.1

The second round were the architects, notably John Wood, who developed a bit of an obsession with the circle and its measurements. Wood eventually translated this into his plan to build the fashionable Circus in Bath – a development that Hill is also willing to link to the invention of the traffic roundabout.

(John Wood’s diagram of Stonehenge, showing The Avenue aligned with the sun. Redrawn by Tessa Morrison.)

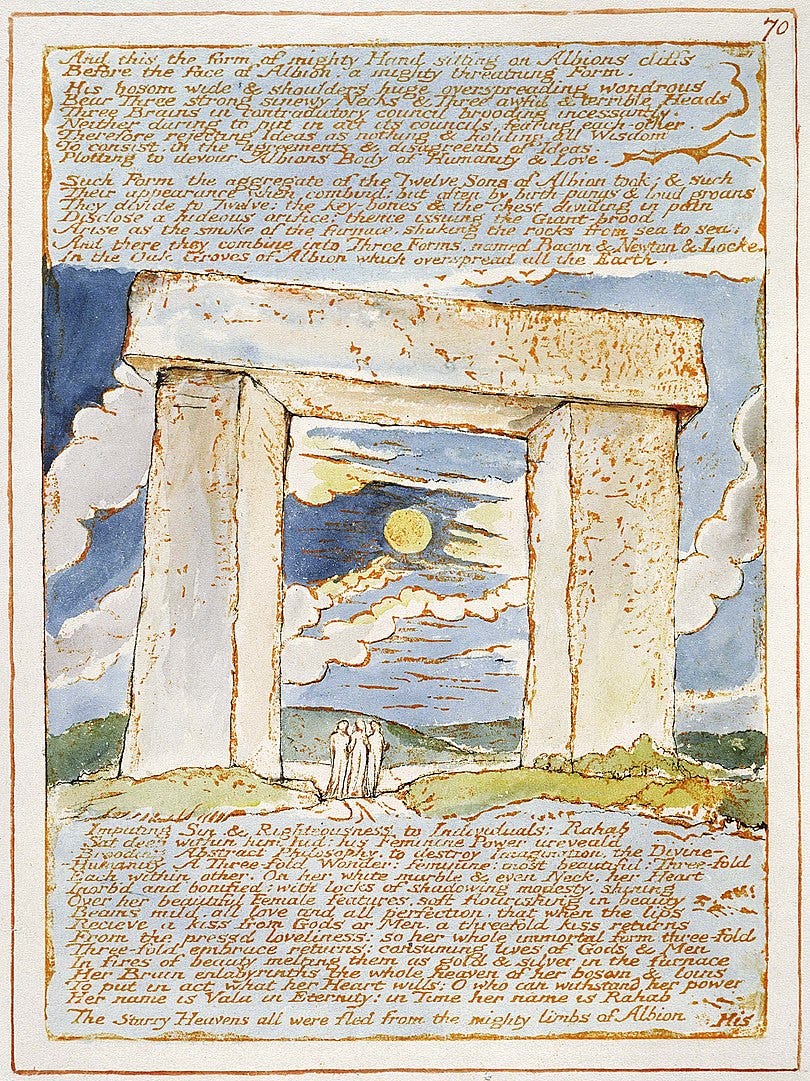

The 19th century is perhaps the domain of the artists and scientists. William Blake visited, famously, but also Wordsworth, Constable and Turner. Fanny Burney and Thomas Hardy wove Stonehenge into novels. The Victorians also had a lot of confidence in the explanatory power of science. Hill quotes the architect James Ferguson, from the Quarterly Review in 1860, saying “Very few of the riddles and puzzles that perplexed our forefathers now remain”. He then goes on to argue that the stones were a “post-Roman Buddhist temple". Even in 1860, this view was a bit of an outlier.

When you read this history, there are three stories that run through it all.

The first is that people found it hard to believe that the stones are as old as they actually are. They were hampered, early on, by the creationist religious idea that the world started in 4004 BCE.

The second is a general disbelief that the builders could have done it on their own without outside help of some kind. This starts with the Royal architect Inigo Jones, in the mid 17th century. The Romans get a lot of love in some of these accounts, as do the Myceneans.

The third is a set of what are broadly colonial assumptions about early peoples. These mean that the place is imagined as more bloody than it was. The Heel Stone, long thought to have been a site of sacrifice, turns out to have been one of a pair of standing stones that has now fallen. The split skull of the child found at Woodhenge–interpreted as a sacrificial victim—has almost certainly just decomposed. As time has progressed, the Beaker People, once assumed to have been conquerors, are now understood to have been traders.

And playing in and around all of these accounts of the stones is the idea of Druids, which turned out to be a fiction imagined by some of the early researchers, notably Aubrey and Stukeley. Stukeley’s Stonehenge book even has an illustration of them. The best way to understand this now is to think of the Druids as an explanatory fiction, to claim the site for the Britons, from the Romans. Of course, this historical fiction has become a contemporary fact.

(Drawing from William Stukeley, Stonehenge. From the University of Glasgow Library.)

The theory that the stones were aligned with the sun is ubiquitous now. It had floated around in writings about Stonehenge since the mid-eighteenth century, and was first seriously addressed by the astronomer Norman Lockyer in 1906, amid some scepticism. Critics of the theory assumed that the ancient Britons wouldn’t have known enough about astronomy to do all of that.

Yet now, at the other end of the century, we have the new hybrid discipline of astro–archaeology. The word first appeared in print in the early 1970s; the first professor, Clive Ruggles, was appointed at Leicester University in 1999.

One intriguing section of Hill’s book, which was new to me, was about the stones at Durrington, near to Stonehenge. Shockingly, much of this site was destroyed—despite protests—so a road could be straightened in the 1960s. This site was also aligned with the stars in a way that complements Stonehenge. Stonehenge is aligned on the midsummer sunrise and the midwinter sunset, while Durrington showed the midwinter sunrise and the midsummer sunset. Hill notes,

Not only does this strike another blow for astro–archaeology, it establishes an elegant link between Durrington and Stonehenge... This makes it seem likely that the same people used both places.

—

(William Blake, Jerusalem, the Emanation of the Giant Albion. The Blake Archive, Public Domain via Wikimedia)

One of the shortcomings of the British Museum exhibition was a lack of material on the cultural context of Stonehenge – it runs only to a few William Blake prints. Hill is good on the 20th century context, both on issues of how heritage sites should be owned and managed, and in the second half of the 20th century on how Stonehenge became something of a contested space between the counterculture and the authorities.

The violent police action in 1986—the Battle of the Beanfield—which brought the free festivals to an end, seems of a piece with the policing of the miners’ strike and the clampdown by the Conservatives on rave music. Similarly, the long fight to regain access to the stones on the solstice by latter-day Druids, in the face of English Heritage’s control freakery. Arthur Pendragon, who had changed his name by deed poll from John Rothwell, figures large in this.

Hill also mentions the famous Stonehenge tribute in the rockumentary This Is Spinal Tap, when the group has a design malfunction with a set designer. I hadn’t realised that the real life Black Sabbath had a related set problem when they tried to incorporate Stonehenge into their 1983 tour set. But the Black Sabbath designer had made the stones far too large.

2: The rise and fall of ‘Corporate Memphis’ and its shiny blue people

You might not know the name of the 'Corporate Memphis’ design style, but you will know immediately what it looks like, because it is everywhere. At Weblog’s blog their managing editor Liz Huang has an engaging article on how that happened.

She characterises Corporate Memphis like this:

The rubber-limbed, brightly colored human figures who tumble across subway ads, Instagram sponsored posts, and big tech websites are instantly recognizable.

If you haven’t a clue what this is about, here’s an example: Alice Lee’s illustrations for Slack.

(Alice Lee)

Huang traces the history of the design. Corporate Memphis emerged in the late 2000s, at a point where there was a certain amount of nostalgia for the 1980s. It was named for the Memphis design group, which came to prominence in the decade and preferred bright colours.

(Memphis Design Group furniture. Photo by Dennis Zanone via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0).

The style influence is obvious, with the bright blocks of color, childish patterns, and oversized geometric shapes... The style rejected the idea of "good taste" and made purposefully flashy and impractical furniture. You might recognize its influence in the design of Pee-wee’s Playhouse or the 1989 show Saved by the Bell. Like the illustration style that took its name, Memphis was criticized during its time for glorifying conspicuous consumption and being a sign of tasteless consumerism.

There’s a history of illustration that links the 1980s Memphis to the modern Corporate Memphis, and Huang namechecks a series of women illustrators such as Yakai Du, Nathalie du Pasquier, Mary Blair, and Charley Harper. It has to be said that some of this work is lovely.

But the re-emergence of Corporate Memphis is down to big tech, and in particular Facebook’s Alegria product. As Huang notes,

The key features of Corporate Memphis include:

- Exaggerated human figures, often featuring oversized, bendy limbs, small heads, and little to no facial features.

- Movement! Figures are often dancing, jumping, cartwheeling, active.

- Skin tones in unnatural shades like blue, yellow, and green.

- Flat colored geometric shapes (vector graphics).

- Bright, whimsical colors. Either bright primaries or soft pastels.

—

(Facebook Alegria, by BUCK Studio)

And after that, tech companies everywhere piled in:

The aesthetic became especially popular for companies making digital services for consumers such as apps, startups, and SaaS in general. From Google Fi to the dating app Hinge, to B2B services like Markup.io, and even as far as the California DMV, the style started showing up everywhere.

There were a few reasons for this. One was the move to flat design—tech designers decided that their customers were literate enough not to need skeuomorphic icons that showed the images of, say, a camera or a clock.

In turn, these flat images were easier to create with vector images:

They were scalable, easy to animate, and easy to create and replicate for however many pages or situations a company might need illustrations.

But it wasn’t just about graphic technology. The Corporate Memphis characters allowed designers to represent people in an inclusive way:

Human figures with unrealistic proportions and non-human skin colors are able to represent customers and communities without ever explicitly including or excluding one group of people. BUCK studio (who designed Alegria) explains, “We designed and built a scalable system rooted in flat, minimal, geometric shapes. The figures are abstracted — oversized limbs and non-representational skin colors help them instantly achieve a universal feel.”

Well, it sounds good, in theory, but pretty much everyone hates it in practice, as Huang observes:

No one is underrepresented, erased, or tokenized by a blue person...but no one is represented, uplifted, or made to feel seen by them either. “You're trying to make marginalized people feel included...by portraying them as these grotesque colored homunculi," complained one online commentator. Minority groups as a whole want more than just a lack of non-inclusion. People want to see themselves authentically represented in advertising and media… Generic figures are never going to communicate that.

It doesn’t have to be like that. Huang commends the work of Jennifer Hom in her illustrations for Airbnb, for example. But one of the problems that Corporate Memphis has to wrestle with is that these bright shiny people are being promoted by companies that we find a little sinister these days, even quite dystopian.

In a Marketplace Morning Report interview, Mike Merrill, who has been credited with coining the term “Corporate Memphis” itself, says, “It is all about this idea of, ‘Trust me. I’m a trustworthy company.’ And let’s not look behind the curtain and see what’s actually going on.”

Or: welcome to 2030:

And there’s one more problem. Because pretty much every tech company has used Corporate Memphis, it’s impossible to use it to distinguish what your brand does or differentiate it in the minds of actual or prospective customers. She has an entertaining sequence of ‘guess the brand’ images. I failed.

Anyway, Liz Huang concludes that we’ve probably passed the point of maximum Memphis, which leaves the question of what comes next. And it turns out that the quirky British futurist Justin Pickard has done an Are.na board that asks exactly that question. It’s well worth spending some time with.

Notes from readers:

In response to my piece yesterday on Web3, Charlie Hyde pointed me towards a set of blog posts by Stephen Diehl. They look fascinating—and what’s not to like about a post called ‘The Tinkerbell Griftopia’? Charlie also recommended a post by David Rosenthal of a talk that Rosenthal had given at Stanford, while noting that it drew a bit of flak.

j2t#287

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Stukeley showed that the measurements of Stonehenge didn’t correspond to Roman units, disproving the idea that the Romans built the monument.