24 June 2022. Cameras | United States

Cameras are getting so small they’ll be in everything. // Secession maps: a disunited States

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

Have a good weekend!

1: Cameras are getting so small they’ll be in everything

Cameras are going to be everywhere. On his blog, Pete Warden explains why, but it’s a simple proposition: they are getting smaller and smaller—small enough to fit into other things without being noticeable—and the their price is now in single finger dollars and still falling.

(Thanks to Charles Arthur’s Overspill blog for the link.)

Lets start with the size:

Soon imaging sensors will be so small, cheap, and energy efficient that they’ll be added to many more devices in our daily lives, and because they’re so tiny they won’t even be noticeable! What am I basing this prediction on? The clearest indicator for me is that you can already buy devices like the Himax HM01B0 with an imaging sensor that’s less than 2mm by 2mm in size, low single-digit dollars in cost, and 2 milliwatts or less in power usage.

The cameras that are coming out of the research labs are even smaller. He shares a picture of a camera shown recently at a conference by the University of Michigan that contained a compete system and sits comfortably on a finger. (Which sounds like it might be the beginning of a hi-tech fairy story).

(Image: University of Michigan)

There’s clearly innovation in this space. Rice University has shown a tiny device that can monitor eye tracking, has dispensed with a lens to enable size reductions, and uses 23 milliwatts of power. We’ll come back to this, but I’m having difficulty thinking about uses of this device that aren’t, we;;. A bit creepy.

The tech story that Warden is proposing in his piece is that these cameras are so small, and so cheap, that they’ll replace sensors in devices, while offering greater functionality than sensors do. Here is his list of some possible applications that take advantage of this:

- Voice interfaces that use lip reading to improve accuracy in noisy situations.

- Stovetops that turn themselves off if they don’t see anyone nearby for a while.

- Water and other meters that share their data digitally with the cloud, without expensive replacements.

- A toaster that pops out the toast when smoke starts billowing.

- TVs that recognize when someone sits down, and who they are, to provide parental controls and personalized content.

- Shades that automatically close when nobody’s around, to conserve energy.

- Gesture recognition for controlling a lamp.

He acknowledges that some of these won’t turn out to be useful, in all likelihood, but equally that once a technology gets to be that cheap you can try out lots of things with it, so other applications will be tested and stick.

Intriguingly, he links to an (undated) article on the Natural History Museum website the discusses the possibility that the Cambrian Explosion happened because creatures evolved eyes. Maybe the analogy is a stretch, but you can see that once people start thinking about visual versions of technology capabilities and affordances, the number of cameras could explode. We could be surrounded by thousands of things. That is, at best, a mixed blessing:

As an engineer I’m excited, because we have the chance to make a positive impact on peoples’ lives. As a human being, I’m terrified because the potential for harm is so large, through unwanted tracking, recording of private moments, and the sharing of massive amounts of data with technology suppliers.

There are some immediate questions here. Even if they are small, if there are millions of them, there will be resource impacts—depending on the materials involved. And we know that we are not very good at using ‘massive amounts of data’ at the moment, so probably won’t be any better at using more of it. But in turn, the way we fix that at the moment is to throw machine learning and algorithms at it, which currently doesn’t seem to turn out well.

As it happens, Pete Warden is already ahead of the curve here. He has a blog post earlier this month discussing the challenge of what he calls ‘ML sensors’:

At the same time as I was thinking about how to get ML into more peoples hands, I was also worried about the potential for abuse that the proliferation of cameras and microphones in everyday devices enables. I realized that the modular approach might have some advantages there too. I think of personal information as toxic waste, because any leaks can be highly damaging to individuals, and to the companies involved, and there are few data sources that have as much potential for harm as video and audio streams from within peoples’ homes.

He has co-written a technical paper that sets out a technical proposal that tries to both machine learning more accessible, while also increasing privacy and accuracy—by walling off the sensitive data—and is looking for comments.

He asks if there should be regulation, and I think he’s right about this:

Even if we don’t get it in the US, will Europe take the lead? Should there be voluntary standards around labeling products that contain cameras or microphones? I don’t know the answers, but I don’t think we have the luxury of waiting too long to figure them out, because if we don’t make any changes we’ll be deploying billions of poorly-secured devices into everybody’s lives as a giant uncontrolled experiment.

2: Secession maps: a disunited States

The US Supreme Court is on a roll at the moment, and not in a good way. From The Guardian:

The US supreme court has opened the door for almost all law-abiding Americans to carry concealed and loaded handguns in public, after the conservative majority struck down a New York law that placed strict restrictions on firearms outside the home.

And having already eroded even further last month the law on campaign funding, we’re still waiting, imminently, for its assault on abortion rights.

There’s more to be said here about what happens when one wing of a tripartite political structure goes rogue, but that will have to wait for another time. Equally, I know the idea of secession of States from the Union has long been unthinkable, because of the history of the Civil War. But: the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the United States Constitution has already diverged from mainstream opinion in general, and radically from mainstream opinion in some of its richest and most populous states. If the Constitution stops providing the rights and the protections that people believe are appropriate, you might need to construct a new Constitution.

American friends will no doubt tell me that everything that follows shows a lack of understanding of the way the US works, and they may well be right. But I’m going to stay with it for a moment.

As it happens, the Brookings Institution explored the secession question in a piece late last year, while acknowledging that it was complex, and therefore unlikely. As a starter, what do you do with the US military?

The result could be a patchwork of differing nations pursuing very different policies on a variety of issues. Whoever formed the majority in the particular areas would specify COVID-19 vaccine and mask rules, adopt or oppose gun control, allow or forbid abortion, raise or lower taxes, and expand or reduce the role of government in health policy. And if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade next year—as many legal experts expect—and abortion law is returned to the states, we will see a vivid illustration of how different states handle that contentious policy area.

Of course, we’d probably see geographical clusters emerging around new groups of States:

Since political polarization plays out unevenly across the nation, one could imagine a situation similar to Europe where a number of separate entities would emerge, including a contingent of Southern states, the Northeast, the heartland, the West Coast, and rural parts of Oregon and Washington joining nearby states.

There was a flurry of discussion about this idea about fifteen years ago, when Dimitri Orlov mischievously argued that many of the pressures that could be seen in the break-up of the Soviet Union could also be seen in the 2000s United States.

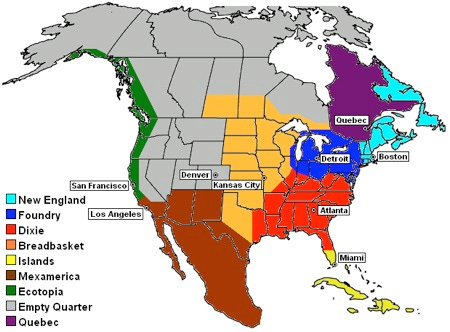

The futurist Kevin Kelly entertained the notion in a blog post, and pointed to Joel Garreau’s 1980s book The Nine Nations of North America.

In past decades bold American thinkers have imagined how the US might break up, but these were more thought experiments indicating the cultural differences within this large country. There’s no shortage of maps showing the alternative arrangements of North American countries. One of the finest is Joel Garreau’ s 1981 scenario of the Nine Nations of North America.

And here’s the map:

(Joel Garreau, Nine Nations of North America)

There’s more detail on this on Wikipedia. I suspect that Canada, which still seems pretty cohesive to me, might have something to say about this, although living with its vast southern neighbour going through the level of turmoil even some of this would involve would be fairly destabilising.

A few years after Orlov, another Russian, Igor Panarin, got coverage in the Wall Street Journal for suggesting that the US would split in 2010. He got that forecast wrong, but timing isn’t always the most important element of futures. Here was his argument:

He predicts that economic, financial and demographic trends will provoke a political and social crisis in the U.S. When the going gets tough, he says, wealthier states will withhold funds from the federal government and effectively secede from the union. Social unrest up to and including a civil war will follow. The U.S. will then split along ethnic lines, and foreign powers will move in.

Unlike the Joel Garreau version, these fractions of the USA all fall under foreign influence. This seems unlikely to me, given the scale of each of these groups, but here’s his map:

Looking at it, I’d be less worried about foreign influence than climate change effects.

Of course, once you start with this ball of string on the internet, it keeps on unravelling. Phil Gyford has a whole set of secession maps in this blog post from 2009, including Panarin’s version above and Garreau’s Nine Nations.

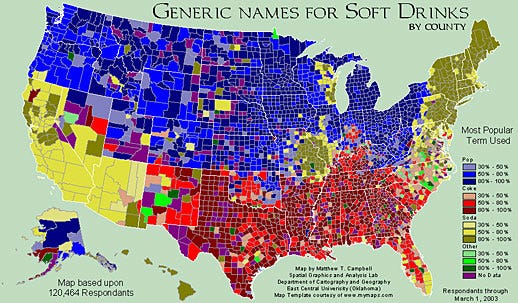

From that post, let me take one, which you could think of as a linguistic map of the United States. It maps the couthry on the basis of whether people call soft drinks soda, pop, or something else:

Clarification corner

I ended up chatting to Wendy Schultz in the break of an online event, and she asked me to clarify something about the ‘Seeds of Change’ method I wrote about yesterday. Her Manoa method was based on weak signals. The language about ‘seeds’ was an invention of the Good Anthopocene Project, and—at least initially—referred specifically to the Project’s Seed Bank.

I realise this might seem like a detail, but there’s enough poor attribution in the futures space without my inadvertently contributing to it. I have corrected the original article to remove any ambiguity.

j2t#336

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.