23 June 2022. Visioning | Flying cars

Seeds of a better future. // Flying cars need somewhere to land.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: Seeds of a better future

One of the tough parts of futures work is helping people step out of the present. The sheer weight of how we do things and think about things right here, right now, gets in the way of people imagining how things can change for the better.

One method that I’ve used—and I’m very much standing on the shoulders of the futurists Wendy Schultz and Tanja Hichert is the idea of ‘Seeds of Change’, originally coined by Wendy in her Manoa scenarios model, and developed by Tanja, working with Wendy, in the Seeds of the Good Anthropocene. Tanja and I presented on this at the Association of Professional Futurists’ conference this week.

In Wendy’s conception, a ‘seed’ is a weak signal or a ‘pocket of the future in the present’. The reason she called it a seed is that the Manoa method, which is designed—her words—to maximise difference, starts by ‘seeding’ a set of futures wheels with several seeds, and the scenarios emerge from this process.

And a seed is defined like this (by the Good Anthropocene Project) as a small sign of a positive future:

‘Seeds are likely not widespread nor well-known. They can be social initiatives, new technologies, economic tools, or social-ecological projects, or organisations, movements or new ways of acting that appear to be contributing to the creation of a future that is just, prosperous, and sustainable.’

The Seeds of the Good Anthropocene project was designed to help communities in Southern Africa identify ways of increasing their resilience in the face of climate change. It combines a number of methods, including Wendy’s Manoa method and three horizons, but its other innovation was to start the process not with a weak signal, emerging at the margins, but with the ‘mature’ version of that seed. What happens, in other words, if that seed had grown in such a way that if has become mainstream. It needs to be grown into a tree, in other words.

In other words, at least for readers who’re familiar with Three Horizons, it has moved from the bottom left of the Horizon 3 ‘visionary’ S-curve to the top.

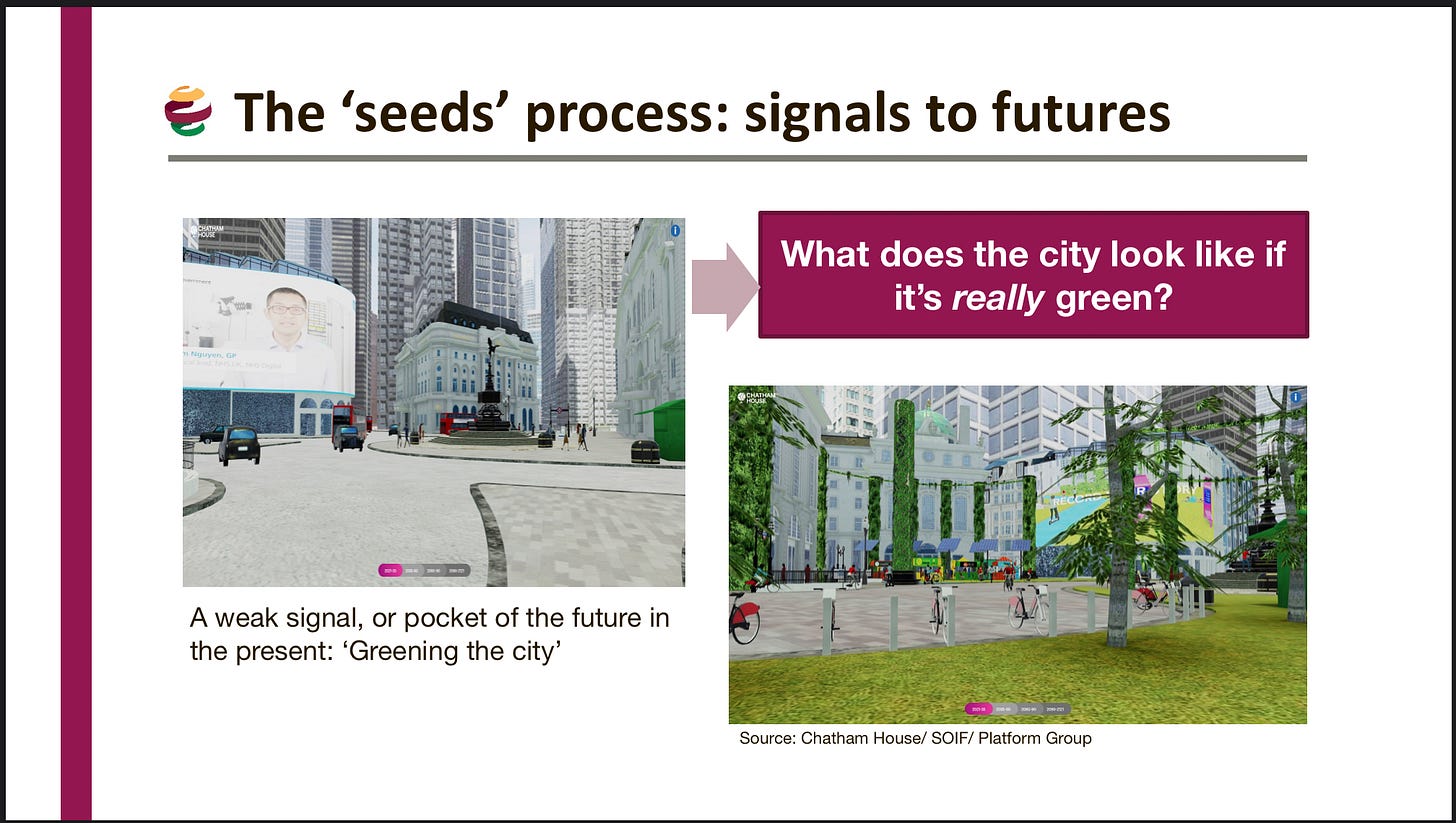

Or to put it another way: planners have started to add trees to urban landscapes, but not with any intent (these images are from a project about re-imagining Piccadilly Circus for Chatham House, animated by the Platform Group). What if we decide we’re serious about trees?

(Image: Chatham House/Platform Group)

I used this approach in the Community Futures/Better Futures Wales method that SOIF piloted last year with Wales Community and Voluntary Action. We started with developing mature seeds, and it opened space in the (virtual) room for people to imagine worlds in which change for the better was possible.

Typically you need to combine this with other techniques—both the Good Anthropocene (borrowing from Manoa) and the Better Futures Wales project used Futures Wheels, if in slightly different ways. And although visioning is, I think, an essential component in helping to build agency, you also need to help people start somewhere rather than left hanging in an imagined future. It’s not coincidence that both projects used Three Horizons as a way to build a narrative about what to do in the ‘entrepreneurial’ Horizon 2.

But it’s also a reminder that the way you ask people about the future matters. Robert Jungk tells a story in his book Future Workshops (sadly out of print) about a group of teenagers whose views on the future had seemed unremittingly gloomy when they were asked about in school

He started his work with them, and found to his surprise, that they were quite animated about possible futures. He asked them what had changed. Their answer: the school asked us about the future we expected, but you asked us about the future we wanted.

Anyway, the handbook for the Better Futures Wales project sets out these steps for building mature seeds, as well as connecting them to a whole community futures process:

Check your potential Seeds of Change against these simple statements:

• A seed is anything that is innovative, already happens and points to a positive future, but is not well-known or widespread.

• A good seed would have people excited and inspire them to think of how their own community could change.

• It should be novel and not exist at scale in your community but should actually be possible.

• It should stretch the imagination and help the community dream beyond your existing conversations.

• It should energise or even excite the group when they discuss it, and they should feel comfortable using it at the start of the process.

If your potential Seed of Change meets most of these criteria, re-write its description in the present tense, as if it already exists and has grown beyond a mere idea to being mainstream or commonplace. For instance, the seed of a single repair cafe has grown into a place where everything can be repaired, or the seed of a single community bus has become a free transport network! Writing the description about your Seed of Change in such a way makes it easier for participants to understand its impact.

2: Flying cars need somewhere to land

I was involved in some work recently about short-range aviation, which covers urban and regional flights. I can’t say anything about that project, because it is shrouded in a web of non-disclosure agreements, but fortunately the IEEE’s Spectrum magazine and others have run pieces since then that cover the issue pretty well.

Futurists are supposed to be open-minded about such things, but I’ve always been sceptical for the need for short-range aviation, or air-taxis, or flying cars or eVTOL (electric Vertical Take Off and Landing, as it’s also known). It has always seemed like a solution is search of a use case, and one that underlined the narrow individual interests of the very affluent rather than social solutions to shared problems.

As the son of someone who worked as an air traffic controller for 20 years, it also seems like a set of mid-air collisions waiting to happen, at least if it is going to provide the kind of point-to-point service that provides faster door-to-door transport for those willing to pay for it.

But what do I know? Investment money is pouring into the sector (in the billions of dollars), prototypes were on show at CES in January, some of the car companies are expressing interest, and innovation policy makers are talking about it as if it is an important new transport sector. Here’s IEEE assessing the state of the market:

If the vision becomes reality, hundreds of eVTOLs will swarm over the skies of a big city during a typical rush hour, whisking small numbers of passengers at per-kilometer costs no greater than those of driving a car. This vision, which goes by the name urban air mobility or advanced air mobility, will require backers to overcome entire categories of obstacles, including certification, technology development, and the operational considerations of safely flying large numbers of aircraft in a small airspace.

Of course, we can be confident that if there is a mass market, there won’t be 250 companies in it. Put like this, it sounds like the auto market circa 1920. There are other problems. One is that although this market needs aviation skills, no aviation company builds at that scale, and they also sit on top of complex supply chains.

And because it’s aviation, and therefore the consequences of crashing are serious, it will need a lot of certification. There are also a lot of different designs, which means that certification is complex. And at the moment, there isn’t a cadre of eVTOL/flying car certificators out there waiting for the planes to arrive to be tested.

So far, even the technological development—which ought to be the straightforward part—is a bit tricky:

Joby, one of the most advanced of the startups, provided a stark reminder of this fact when it was disclosed on 16 February that one of its unpiloted prototypes crashed during a test flight in a remote part of California. Few details were available, but reporting by FutureFlight suggested the aircraft was flying test routes at altitudes up to 1,200 feet and at speeds as high as 240 knots.

The critical issue in terms of the development of the sector is not so much the flying but the landing and taking off. The Next Web reports that the first prototype ‘vertiport’ in the UK was opened in Coventry by urban-Air Port in April, and their article reviews many of the issues.

(Image: urban-Air Port)

Location matters—it needs to be close to transport hubs. The Coventry location is effectively a car park near the rail station. But some of the visions for air taxis have the craft leaving every few minutes, which means you need parking and waiting space for them (there’s not much of that in the Coventry site). The craft also need to recharge.

There are currently rules about how far craft have to be apart from each other when passengers are embarking or disembarking (around 60 metres for helicopters in the UK, although some of this is specifically because of the down-draught from the rotors). This generates further space requirements.

We still don’t know what kind of security protocols regulators will expect, and some of the industry expectations about how quickly they’ll load and leave seem wildly optimistic.

Uber Elevate proposes a turnaround time of five minutes in between departing passengers and the next vertiport take-off. It is logistically questionable. Think about the time it takes to get off a plane, get on a bus, and arrive at the terminal, for instance.

Again, to get close to that kind of operational frequency suggests that you’ll be loading a number of different craft in different locations on the same site, which again suggests that you’re going to need a bigger site. Again, the chances of finding that close to a transport hub seems small in most of the locations that I’m familiar with.

Again, the range of designs and shapes in the development space at the moment makes this more difficult—there are reasons why airlines have converged on a small number of designs. That will likely happen, but it will take time.

And it will also take a while before we’re able to agree a set of safe operational procedures that allow us to fly things around at relatively low heights in built up areas. It’s always the infrastructure and the business model that are the pinch point in the development in these kinds of technologies.

My own bet is that we’ll see drones continue to evolve for cargo distribution, and as they become more sophisticated (and powerful enough to carry heavier loads, which needs better batteries) we’ll see them adapted for carrying passengers, probably using existing helicopter landing areas initially. The most likely early use case is as a cheaper way of delivering air services that currently require helicopters. I suspect the investors backing those 250 or so air taxi companies might be disappointed.

j2t#335

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.