24 January 2024. Business | Digital media

Why business futures isn’t about managing uncertainty. // Digital media algorithms, advertising, and the health of young girls. [#536]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Why business futures isn’t about managing uncertainty

I co-wrote—with my sometimes colleague Emma Bennett—a short piece on why focussing on uncertainty is not a useful way for organisations to imagine the future. It’s been published to the SOIF website, so I’m also sharing it here.

Talking about VUCA—Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity—is an unhelpful way to think about the future. It creates anxiety and it makes it harder for us to act. In practice, every purpose-driven business knows where it needs to get to to have a sustainable future. The challenge is how to get there.

Unsticking ourselves from VUCA

The world is more confusing than it used to be. Everyone can tick off the list: climate change, populism, pandemic, Ukraine, and more. But in the face of all of this, it is easy to feel stuck: to feel that, no matter what you do, it will be the wrong thing. Chess players have a word for this: zugzwang. You have to move, but once you have moved, you will be in a worse position.

These challenges affect the internal management of organisations as well. Technology was supposed to increase efficiency and improve customer management, but instead delivers supply chain disruption and customer noise.

Younger staff have different expectations about work and, often, different business values from their managers. People want to work for purposeful organisations, but the line between purpose and greenwashing can be thin.

In the face of this difficult, and different, operating environment, we are told that strategy is dead and planning is impossible. Agility and adaptation are said to be the answer. It’s all about volatility and uncertainty. Other acronyms tell a similar story.1

But treating the world as if everything is uncertain, and that the best we can do is to respond to the unpredictable, forces us into inaction. The concept of VUCA makes us more anxious, rather than less anxious. It creates “a sense of over-stimulation and overload,” as Sandra Waddock of Boston College argues.

Anxiety and overload are a terrible combination. They prevent us from making meaningful choices. They lock us into incremental variations in business as usual even though we know that it is becoming ever harder to make business as usual work. Worse: this inaction is both a symptom and a cause of the worsening larger environment. You can’t address 21st century problems with 20th century tools.

The half truth about uncertainty

The notion that we are living in uncertain times is only a half-truth. Yes, we are living in uncertain times. But if we are interested in a future that is sustainable for our organisations — economically, socially, environmentally—the path to that future is surprisingly certain. Axa said at the time of the Paris Accord, “A four degree world is uninsurable”. We have learned since then that a two-degree world is probably uninsurable as well. Maybe even a one and a half degree world. This means that the target area for the future business is tightly defined by climate crisis and biodiversity loss. In business terms, we are trying to land the plane on an atoll in the middle of the ocean.

(Wake Island/Atoll. Photo by Blatant World. CC BY 2.0)

For values-driven, purposeful organisations—whether in the private, public or third sectors—the need for significant transformation in coming years is clear and certain. The societal, economic and environmental systems we operate within are under growing pressure, and technology innovation alone will not provide a silver bullet that allows business as usual to continue.

We know that new business models, new ways of navigating resource constraints and new ways of managing staff and stakeholders will be required. Many leaders are already grappling with the scale and reach of transformation needed, for example to meet net zero carbon targets within the constraints of existing assumptions and operating models.

Finding the future

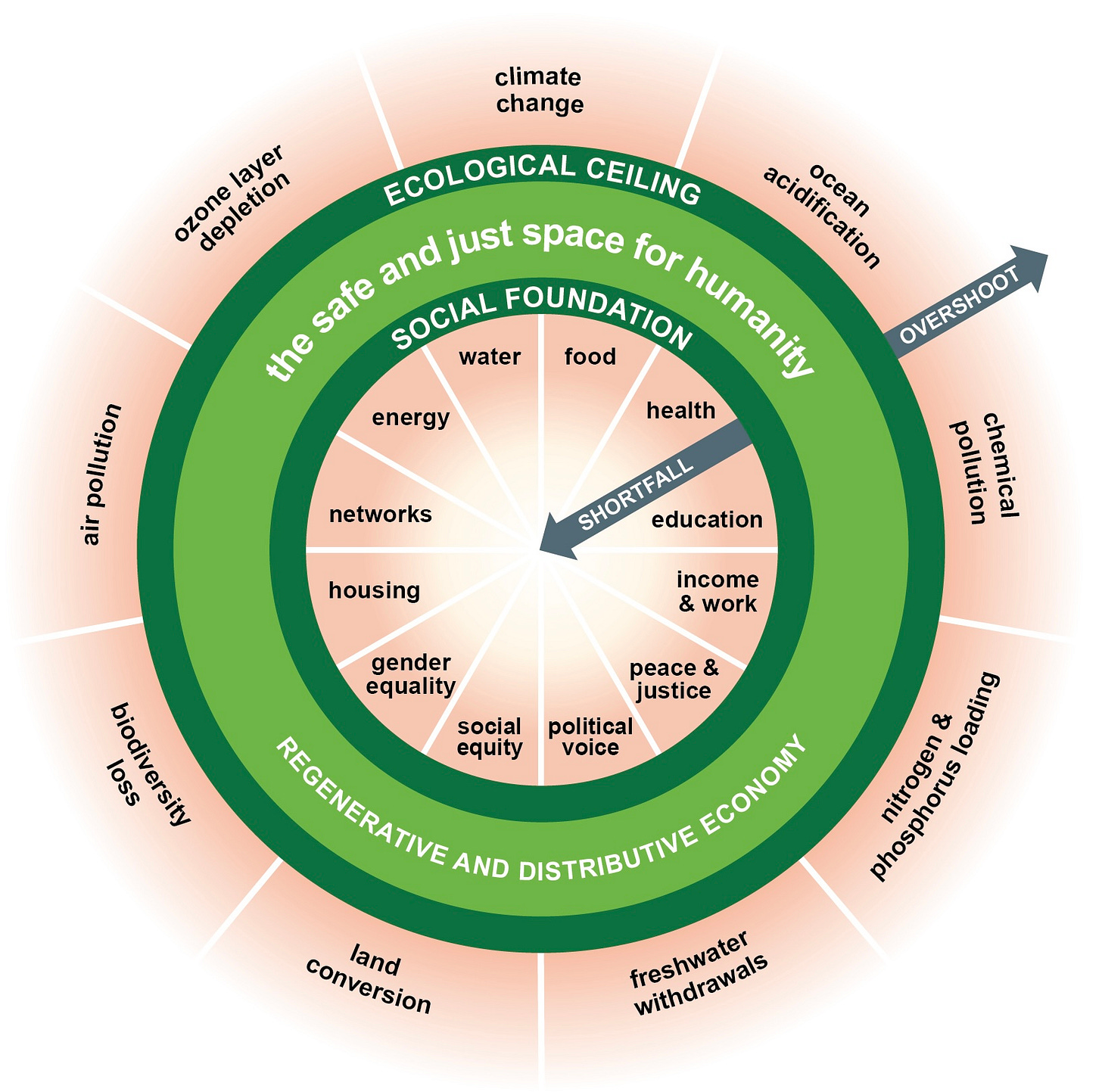

We also know quite a lot about what the atoll looks like. Different organisations have described it well enough. For example, drawing on FutureFit’s open source benchmarking tool, we can see that the businesses that survive in a sustainable future need to be able to operate within the planetary boundaries, as well as economic and social boundaries.

The corporate business model of exporting external costs into the rest of the system is not sustainable in this future world. In effect, they become the equivalent of ‘doughnut’ companies, borrowing Kate Raworth’s economic model, operating in a safe space between the ecological ceiling and a viable social and economic floor.

(Kate Raworth’s doughnut model. Via Wikipedia.)

This is a pragmatic view as much as it is a moral one. Either we manage our way to businesses that are stable and viable, or the system will manage it for us through continued decline, even collapse.

Using strategic futures as a map

If the outlook is relatively certain, what remains uncertain is how you get there. Transformation is a complex journey that requires navigating a lot of legacy issues at the organisational level. This is where strategic foresight has particular value to add. Foresight helps organisations to identify opportunities to transform, and to identify and then harness the sources of agency and energy needed to get there.

Strategic futures work complements other types of business planning methods, but they come into their own when it is possible to articulate the shape of the future that needs to be realised. Although futurists often talk about probable futures, possible futures, and preferred futures, and this opens up uncertainty about the future, we are now only looking at one future: the future that is necessary to avoid collapse.

We can sketch out the operating principles of such a future business, even if some of the detail remains out of focus. And from the operating principles, we can also identify the building blocks that need to be in place to get there, the constraints that we have to manage, and the leverage points that we can use to accelerate the transition, using tools such as the Three Horizons Framework, actor mapping, and backcasting, and so on.

Change is going to happen. The question for the future of business right now is whether we want to be the agents of change, or have change happen to us.

The PDF of this article can be downloaded from here.

2: Digital media algorithms, advertising, and the health of young girls.

At the Persuasion newsletter, Freya India has an article about the impact of social media on young girls. The makes it all sound quite neutral, but in fact the Persuasion headline and sub-head name the issue more clearly:

What the Algorithm Does to Young Girls: Unpacking the toxic treadmill of internet addiction and low self-esteem.

It starts with a bang:

Let’s start with the young women who transform their faces. You know the ones: they have their lips injected, noses chiseled, skin blurred with Botox, and cheeks pumped with filler, each funneling their previously unique features into the same Instagram Face .

Then, after this process, which is sometimes quite slow, they realise that they have destroyed what they used to look like in pursuit of an online look:

Molly-Mae Hague, for example, a reality TV influencer here in the UK, recently admitted to having no idea how she ended up destroying her face: “I literally looked like a different person. When I look back at pictures now, I’m terrified of myself. I’m like, ‘Who was that girl?’ I don’t know what happened.”

She might not know, but Freya India suggests that it might be a good idea if the rest of us did. She’s making some strong claims here, but she argues that ‘Instagram Face’ is

one manifestation of what I see as the driving force behind much of Gen Z’s growing and global mental health crisis. It is the end result—the inevitable end-point—of what I think of as the algorithmic conveyor belt.

(Image: Cubism-Inspired Female Portrait (detail), by Autlyx-Art. DeviantArt. CC BY-NC 4.0)

She charts the life story of someone born in 1999–so at the older end of Gen Z—against a set of online ‘innovations’. Instagram comes out when you are 12. A couple of years later, the editing app FaceTune arrives, and soon everyone on your feed looks perfect. You start editing yourself, and your face starts to change. Which is just as well, because you were fed up of the look of your face compared to those of your social group on Instagram. And then the algorithms get to work.

What the algorithms do is restructure your feed:

Instagram now serves you not just photos of the friends you follow but of “influencers”—beautiful women from all over the world, selecting the ones that make you feel the most insecure. Soon you get ads to fix your flaws: Botox; fillers; Brazilian Butt Lifts! By the time TikTok comes out you’re 18, and your feed tracks you even faster. Hate your nose? Try this editing app. Not enough? Try this video editing app. Want it in real life? Nose jobs near you! Suddenly you’re in your 20s and you’ve transformed your style, your face, maybe even your body. And yet you are still insecure.

This wasn’t a fast process. It was more like drip-feed, which is perhaps the worst of it. But the result is that we have skyrocketing rates of cosmetic surgery:

Little by little, the algorithm learns what keeps you watching. And since the most negative and extreme posts get the most engagement, very often your feed will become an endless stream of content that makes you feel worse about yourself.

So this ends up being about more than just self-image. It goes direct to your mental health. And this is an explicit connection that India makes in her piece. She’s about the same age as the cohort that she is writing about, and she recalls mental health being visible in social media when she was 12 or 13:

The first YouTube stars started opening up, tentatively, about their anxiety and depression. Celebrities confessed to struggling. Mental health communities formed on Tumblr. I learned about anorexia, self-harm, and disorders like ADHD. It all felt important to talk about.

But, of course, in the world of advertising driven digital media, no-one gets the change to just to talk about things, no matter how important they are:

Platforms like YouTube began to reward cheap, clickbait posts to boost advertising revenue, meaning that users were being served more and more sensational content. Slowly we went from watching influencers talk about anxiety to live-streaming their panic attacks.

And where content goes, advertisers are sure to follow. You might have ADHD? What you need is Ritalin. And so on.

And where have we ended up? With genuine conversations about mental health cheapened, monetized, and often trivialized into TikTok trends and fashion accessories... With a #mentalhealth hashtag on TikTok with over 110 billion views, and millions in my generation taking medication for their deteriorating mental health.

She acknowledges that not all of this can be explained just by algorithms. But she argues that this “conveyor belt” effect can explain some of the sharpening anxieties in the Gen Z world that lead to poorer mental health.

Of course she notes that the social media companies would say that this is down to us. Nick Clegg, for example, the lavishly well paid (my phrase, not hers) President of Global Affairs at Meta, argues:

our social media feeds are shaped by our own choices and actions, with algorithms helpfully organizing what we see to align with our preferences.

For some reason, a famous quote by Upton Sinclair comes to mind at this point.

Because, India is clearly right when she says:

we know that these platforms are engineered to be maximally addictive. We know that they use persuasive strategies like personalized feeds, the infinite scroll, and autoplay videos to keep us online. We know that they constantly surveil us, collect our personal data, and can identify when we feel “insecure,” “worthless” and vulnerable to advertising. And we know that they are aware of the adverse mental health effects.

And while she says, mildly, that “a 12-year-old’s mind is no match for a giant corporation using the most advanced AI to manipulate her behavior”, I think I might go a bit stronger here. Because there are whole areas of life where there are, for very good reasons, well-developed restrictions on the commercial and other relationships that companies can have with young people.

India recommends that parents of the children of the generation that is following hers should delay letting their kids having social media accounts until they are 16. There’s a burgeoning campaign in Barcelona where parents are organising against mobile access for their kids. As one of the organisers told El Pais:

The problem is access to social media. They are not mature enough. WhatsApp is for 16-year-olds. What are we doing giving WhatsApp to a 12-year-old? Even if they don’t use it at school, they continue cyberbullying at home. Let’s be conscious families and not give them a weapon that, if it were tobacco or alcohol, we would not give them. It is not regulated, and we give it (to kids) as if it were nothing.

This shouldn’t be down to individual parents. If there is social harm being done—and the evidence gets clearer all the time—we need more and better regulation. No matter what Nick Clegg thinks.

j2t#536

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Such as TUNA: Turbulent-Uncertain-Novel-Ambiguous. Spot the desperate attempt for a sliver of distinctiveness.