Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Beavers are the great ecologists

I never got around to writing about a long piece by Adam Ramsay in April on Byline Supplement about the re-introduction of beavers to Tayside. Ramsay is the c0-leader of the UK Green Party, and the child of Scots farmers who were involved in bringing the beavers back. I think it’s well known now that beavers are terrific at restoring habitats, and the article touches on this, but I was at least as interested in the politics of it all.

He says that they have transformed the land that his parents’ farm stands on,

from a low-productivity upland farm criss-crossed with drainage ditches, into a rich, biodiverse wetland, a haven for birds, mammals, fish and amphibians.

In the 1990s, his father had learned at a conference that beavers had been a native species in Scotland until the 1600s, until they were hunted to extinction to their pelts. As a landowner, he was able to find a way to bring them back, at least to his land, although it involved skating around the edge of the law, as it then stood. The newly-created Scottish government, led by the Labour Party had decided against changing the law to permit beavers to be reintroduced.

It happened that the Ramseys’ land was right for beaver habitat. The legal trick was that they would be reintroduced to enclosed areas (“legally a bit like pets”), so that populations would be established by the time the government did change the law.

(Photo: Paul Stewart/flickr, CC BY 2,0)

So where do you get beavers from? Germany, it turns out. Bavaria’s Bibermeister has the responsibility of relocating Bavarian beavers who have caused a nuisance, and in due course, a couple of pairs arrived, and later, a third pair for a neighbours’ farm. And, eventually, when the Scottish Nationalists took control of the Scottish Government, a beaver trial was introduced, but in such a way that it was almost bound to fail.

(You see quite a lot of this behaviour by organisations in response to change. The systems theorist Donald Schön gave it a name: ‘dynamic conservatism’, in which the organisation does the minimum possible in response to change.)1

By that time, quite a lot of these quasi-captive beavers had already escaped, and so, in this official view, they needed to be trapped. On Tayside, locals were less keen on this: they would pee on the traps so the beavers would be warned off by the scent. Tayside became known to politicians as a place that campaigned for beavers to be in the wild. And eventually, in 2016, the Scots government relented and changed the law. Beavers were now a protected native species.

Except: this isn’t as good as it sounds. It only meant that farmers needed a licence to kill them, and there was no shortage of licences issued. Ramsey’s mother campaigned for a policy of translocation instead (moving unwanted beavers to locations where they were wanted, rather than killing them), and eventually the Scots government agreed to this as well.

In the meantime, there had been beavers on the Ramsey farm for a couple of decades, and scientists had been monitoring the effects. In truth, the effects were pretty visible:

beaver dams trap pollution from farms, cleaning up water, boost invertebrate and water plant numbers, and are good for trout. But you don’t need to be a scientist to see the improvements. Newt and frog armadas attract heron, goosanders, kingfishers, sandpipers, and dippers. Otters play. Last year, ospreys nested.

Other studies have shown that beaver dams help regulate rainflows, catching water during rainy periods, allowing it to flow during droughts, reducing soil erosion, acting as a firebreak:

[O]ther species came to depend on those ponds, forming complex webs of relationships. Fungi and bugs evolved to harvest the woodchips they drop when they chop trees. Even the trees evolved alongside beavers: the species they tend to gnaw spring back, producing coppiced thickets of undergrowth which themselves create new ecosystems, often richer than the original vertical tree.

It seems likely that had we not exterminated the beaver, Britain’s countryside would be in better health. We’d probably have more temperate rainforest, for example. And now, the National Trust has released the first “unfenced” beavers in England, in Purbeck in Dorset. They had been trapped in Tayside, where there are now more than a thousand beavers. The results will only be good:

these rodents are building dams to make ponds for frogs, toads and fish; insects, birds, and mammals. The ecosystems they create will, over the next few years, start to flourish. Life will revive. Sometimes, amidst horrors, good things happen too.

(Beavers at work. Photo: Richard Sutcliffe/ Geograph, CC BY-SA 2.0)

One of the reasons I was reminded of this piece was because I saw an article over the weekend in the grimly designed Club Amsterdam newsletter that used the beaver dams as a metaphor. Andrew Wiebe specifically proposes them, drawing on the work of the indigenous scholars Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Audra Simpson, professor of anthropology at Columbia University, as a metaphor for how we should create and sustain indigenous spaces:

Both situate the beaver dam as an ethical bridge between worlds. They also describe the beaver dam as a site of protest. It is one in which Indigenous thinkers and dreamers build their own sustainable and ethical infrastructure.

The inter-relational nature of the beaver dam is also a useful part of the metaphor:

This relationship between beavers and the human world is seen as an important part of maintaining harmony in Indigenous communities. As Betasamosake Simpson says, harming the beaver harms everyone in the community because the beaver brings water and life.

This leads in the piece to a call for values and ethics to be embedded in infrastructure, drawing on the work of Michelle Murphy. This is from the linked article:

A basic lesson from Indigenous reproductive justice is that “violence on the land is violence on our bodies.” What happens to the water is what happens to its relations.

Wiebe is specifically interested in a live project in which better internet connections are being rolled out to Canada’s indigenous communities, in a classic partnership between the government and commercial partners:

These structures are part of a larger power dynamic being exercised by both the government and private companies... Re-envisioning how we engage in building infrastructure as a relational practice, we can build like beavers and aim for structural regeneration and sustainable digital infrastructure in the community's hands.

I’m not actually sure if this metaphor completely works, but all the same there are Canadian organisations who are at work building relational approaches to infrastructure. Wiebe writes about Adisöke, the future Public Library in Ottawa. This “has Indigenous partners embedded within its design, infrastructure and future.”

Obviously libraries are seen as forms of cultural and physical infrastructure in a way that the internet isn’t (even if it ought to be.) This means, as Wiebe says,

Communities are not given control of the infrastructure intended to regenerate community.

If we’re taking the beaver dam seriously as a metaphor, we should be thinking more about the ecologies that infrastructure generates, and the relationships that these create.

2: Long-distance war

I gave up being a journalist in my 30s because I realised that on pretty much any subject of real importance, news—in my case broadcast news—had nothing to say of any consequence in terms of understanding what was going on. If anything, journalism has got worse since then. The current attacks by Israel and the United States on Iran are a case in point. If you want to understand them, the news is not a useful guide.

The first observation about the war, from Adam Tooze’s Chartbook on Substack, is just about how historically anomalous it is to have combatant states trading attacks with each other at a distance of more than 1500 kilometres — just shy of the distance from Berlin to Moscow. This is, incidentally, a terrific piece of analysis and research.

There is no land border between the two countries, and the counties in between—Syria and Iraq—are not parties to the war.

From Israel’s perspective:

To attack targets in Iran, Israel’s small but high-tech air force flies thousands of km on each sortie, across foreign air space and sparsely populated territory. Israel’s F15, F16 and F35 fighter bombers can operate at these long ranges thanks to refueling and the routine violation of foreign air space. This would not be possible if Iran could mount a significant counter to Israel’s incoming air force.

Tooze is an economic historian, and he notes the differences in the material base of the two countries that create this resource difference. Over 30 years, economic sanctions on Iran have hobbled its economic development, while Israel has done just fine.

Which, just from a war-fighting point of view is handy, because modern planes are awfully expensive.

The procurement price of a single, upgraded Israeli F35 stealth fighter is $110 million and that does not include the cost of servicing and maintaining them. Israel has over 40 F35s in its operational fleet.

While its bombs are less sophisticated than its planes, Israel’s relative air superiority means that it can bomb pretty much what it wants. Iran’s air fleet is ageing and its planes no match for the Israeli Air Force. On the other hand, it has invested heavily in ballistic missiles, which are not cheap, but they are a lot cheaper. A typical missile comes in at between $2 million and $10 million, according to a helpful table in the article.

Iran response’s to Israel’s bombing is to fire missiles towards Israel, 1000 miles away. Linger over this statement. This too is a radical and anomalous fact. Israel flies its aircraft a thousand miles to drop bombs. Iran fires missiles, a thousand miles back the other direction... A large salvo of ballistic missiles might run to $200 million, but it pales by comparison with the tens of billions of dollars embodied in Israel’s 200 strike aircraft.

There’s a technological history here, of course. Most of this missile technology emerged originally from the post-war Soviet Union, which developed them from the expertise of captured German rocket scientists (as did the US, of course). The Soviet Scud missile was fired in huge numbers by both sides in the Iran-Iraq war. Both the Iranian and the Russian missile programmes, however, have moved on to far more accurate missiles in the 21st century. Indeed, Russia has fired a lot of Iskander missiles at Ukraine from ranges of 400-500 kilometres.

And technically, Iranian missiles reach heights of several hundred kilometres and speeds of Mach 5 before coming back down towards their targets.

(Image: CSIS Missile Threat via ABC Australia and Adam Tooze/Chartbook)

So, of course, Israel has a complex of missile defence systems, starting with the local “Iron Dome”—obviously the name itself is a form of propaganda—and working out to the regional “Arrow 3” system.

Arrow 3 has its roots in the 1980s, and Ronald Reagan’s Cold War dream of a “Star Wars” defence system that would shield America from Soviet attack. The Arrow programme, going back to the 1980s, has largely been paid for by the US with Israeli technical expertise doing the work. Arrow 3 had its first operational success in 2023, when it shot down a Houthi missile in the exo-atmosphere, more than 100 km up.

But these defence systems aren’t cheap either.

According to Israeli estimates, its interceptions of incoming missiles during an intensive bombardment costs as much as $285 million per night. Each Arrow 3 interceptor is priced at $2 million. And more importantly than price, it is physical stocks and production capacity that are limited. Even sharing the production runs on a 50/50 basis the military-industrial establishments of Israel and the US cannot keep up with demand for the interceptors.

This may be more about the materiel of the war than you really want to know, but it is striking that the most technologically sophisticated warfare, with only a modest requirement for military personnel, still comes down to the production of hardware. And according to American analysts, we don’t know which side will run out of missiles first.

In his piece, Tooze nods to, but parks, the other elements of the war ignored by news media:

[T]he huge international effort to anathematize the idea of an Iranian nuke; or the conflation of Israel’s utterly ruthless strategy of preemption and regional dominance with anodyne assertions of its right to self-defense.

To go there, I turned to the radical writer Tariq Ali in the Sidecar blog that is run by New Left Review. It’s a long piece that takes a synoptic look at Iran’s position within the history of the Middle East over multiple decades.

I’m not going to try to summarise it, but the post touches on something like three quarters of a century of Western manipulation and hypocrisy in its dealings with Iran, starting with the 1953 coup that overthrew the elected government and installed the Pahlavi dynasty. The involvement of America in the vastly destructive war between Iran and Iraq after the coup that overthrew the Shah is also referenced:

Hundreds of Iraqi missiles hit Iranian cities and economic targets, especially the oil industry. In the war’s final stages, the US destroyed nearly half the Iranian navy in the Gulf and, for good measure, shot down a civilian passenger plane. Britain loyally helped in the cover-up. Since then, the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy has always put the regime’s survival at its centre.

But it is worth pulling out the elements about Iran’s so-called nuclear “threat”, since the invocation of this by American and other leaders is so clearly performative.

As Trump’s Director of National Security, Tulsi Gabbard, said in March:

‘The Intelligence Community continues to assess that Iran is not building a nuclear weapon and Supreme Leader Khamenei has not authorized the nuclear weapons programme he suspended in 2003.’

This assessment was based on the work of International Atomic Energy Authority inspectors, who, in Tariq Ali’s assessment,

have simply been acting as willing spies for the US and Israel, providing pen-portraits of the senior scientists who have now been killed.

The history of the Iranian uranium programme is also skated over in the current coverage. It originated in the 1970s under the Shah, with US support. Dick Cheney was involved. When Khomeini came to power in 1979 he halted it, thinking it un-Islamic.

But the impact of the Iran-Iraq war, and the geopolitics of Iran’s situation—surrounded by nuclear powers (Russia, India, Pakistan, Israel, together with a circle of American military bases)—meant that he relented. All the same, what Iran currently has is quite a long way from a bomb: its enriched uranium is still short of weapons grade, and there is no evidence that it has assembled the other parts you’d need for an actual bomb. Hence the IAEA assessment.

And frankly, nothing that Iran has done since then has made any difference to the rhetoric. It really doesn’t matter whether it co-operates or not, or whether it allows inspections or not, since the sanctions don’t get lifted and Western noise about Iran continues. (This isn’t just a Republican obsession: Hillary Clinton was just as hawkish.)

And as John Mecklin, the editor-in-chief of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, noted on Sunday, after the US bombing of alleged nuclear sites in Iran;

Before and after Saturday’s attacks, many experts said that direct US military action would likely make a negotiated end to Iran’s nuclear program all but impossible and could lead the country to decide to pursue nuclear weapons quickly and covertly. James Acton, a director of the nuclear policy program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote that “any hope for diplomacy has now vanished (which was NOT the case before the U.S. attack).”

Tariq Ali reports (unsourced) on demonstrations against Israel in the streets of Iran:

Hijabless women have been demonstrating in the streets, chanting ‘Get an atom bomb’. One of them told a reporter: ‘In parliament, they’re discussing closing down the Hormuz Straits. No need to discuss. Just close them down.’

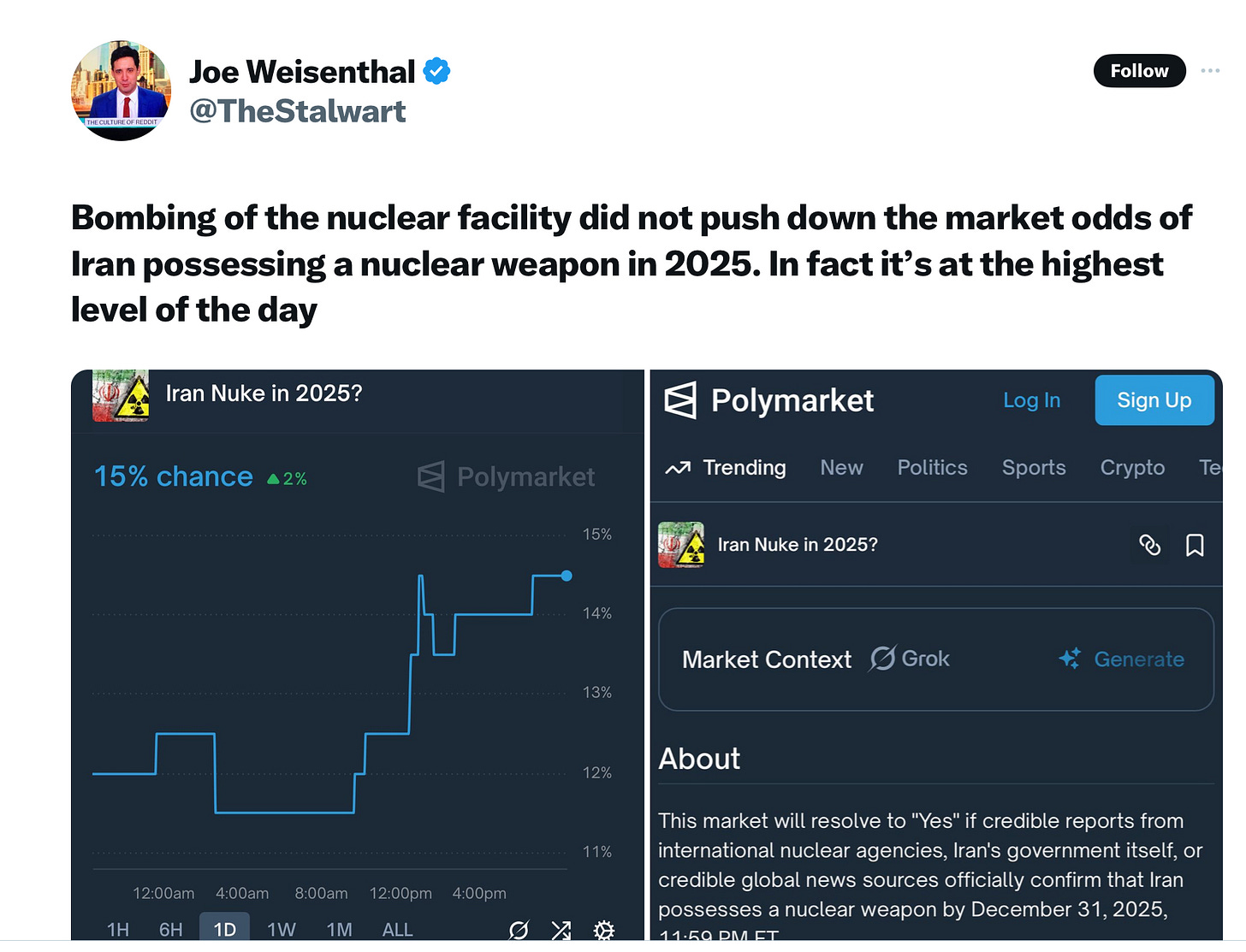

(Joe Wiesenthal/ Twitter-X, 22 June 2025)

And if you need evidence of Western hypocrisy here, it would be this: there has been endless pressure on Iran about compliance with international nuclear rules, while none of this has been enforced on Israel, as Tariq Ali notes:

Israel has not joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, has not signed the Biological Weapons Convention and the Ottawa Convention, has not ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention and has disregarded international law and UN resolutions for decades... This is what a rogue state looks like.

j2t#643

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

“The system as a whole has the property of resistance to change. Sometimes we talk about this property as though it were inertia... But it is a rather passive metaphor and I propose instead that organisations are dynamically conservative: that is to say, they fight like mad to remain the same.” (Emphasis in original).