23 June 2023. Cities | Film

The design challenge of branding a city // The ‘most significant’ political films [#470]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: The design challenge of branding a city

There’s a striking piece by Dalia Dawood at It’s Nice That on the branding of cities, that stretches across the apparently controversial tweak to the branding of New York to the challenges of branding a city that doesn’t exist yet—Indonesia’s new capital city Nusantara. The images probably say as much as the text does, so I’ll link some short sections with the pictures.

New York first, since Milton Glaser’s ‘I Love New York’ motif probably launched the idea of urban branding, so changing it was bound to attract brickbats as well as bouquets.

(WE ❤ NYC campaign (Copyright © New York State Department of Economic Development, 2023))

The article quotes from Maryam Banikarim, who ran the NYC campaign:

The aim of the rebrand was to infuse pride in New Yorkers and “drive civic action” by encouraging citizens to volunteer in their communities. “This is a moment for ‘we’ not ‘me’,” she explains. “The campaign isn’t trying to replace the original mark; it’s designed to exist alongside it and bring NYC residents together. Whether you love the mark or hate it, do something for your city.”

The theory of city- or place-based branding is that it needs to find the set of attributes that represent a powerful sense of place, and which represent the “unique character” of the place.

In New Zealand Christchurch Ōtautahi was devastated by an earthquake in 2011, and to some extent is still recovering from that. Its rebrand was designed to attract external visitors and investors.

The designers Resonance Consultancy spent time talking to residents, business and visitors:

They discovered that its image as the “Garden City” was important, as well as being a good place to balance work and leisure, leading them to create the promise: “Christchurch is a playground for people.” Jeremie (Feinblatt of Resonance Consultancy) calls this process “from logic to magic”.

(Christchurch Ōtautahi (Copyright © Christchurch, 2023))

The logo incorporates the city’s name in both languages and its dual lines are a nod to ‘haehae’, a technique used in whakairo (Māori carvings), plus the two sides of the Avon River’s banks.

If I’m honest, I found this a bit underwhelming, although I can see that in an age where people emphasise the ‘liveability’ of cities it might work. But doing city branding is a tough challenge. Once launched it needs to work for 10 years or more. You can see that simpler might be better.

The article looks at Oslo and Madrid as well. The Oslo campaign was in the ‘refresh’ business, finding a way to update a century old city seal, which shows the city’s patron sait, St Hallvard, making it more modern, more minimal, and easier to combine with other messaging:

“Less clutter, more clarity” was their strategy, he says, plus drawing on the city for inspiration when choosing colours and fonts. The blue and green hues of the brand represent everything from streetcars and the fjord to Oslo’s parks, while the bespoke font, Oslo Sans, is inspired by the city’s street signs.

(From the old St Hallvard to the new. Copyright © Knowit Experience (formerly Creuna), 2019)

And since I love typography, here’s Oslo Sans.

(Oslo Sans (Copyright © Knowit Experience (formerly Creuna), 2019))

Of course, when you’re branding an unbuilt city, none of the constraints above apply, but you also have nothing much to work from. The Indonesian Association of Graphic Designers (ADGI) is helping the government develop the logo for the country’s new capital, Nusantara. Diaz Hensuk sits on ADGI’s board of advisors:

“There’s no culture yet, there’s no people yet,” he says. “We have to create our own image through the design.” The narrative ADGI has devised seeks to present Nusantara as “a home for all” to meet the government’s professed aims of promoting economic equality and inclusivity, and decentralising the country by shifting the focus from the dominant island of Java.

If in doubt, hold a competition, which is what AGDI did, inviting submissions from its members. The winning entry, unveiled at the end of May, went for a tree theme:

(Aulia Akbar ‘s) logo is called “Pohon Hayat Nusantara” (Nusantara’s Tree of Life) and was inspired by the symbolism of trees from west to east Indonesia, representing the rich biodiversity in Indonesia’s ecology.

(The winning visual identity design for Nusantara (Copyright © Aulia Akbar from ADGI Bandung Chapter, 2023)

As the article suggests, a good city brand is about increasing the cohesion of the city, creating more of a sense of being and belonging. It’s designed to connect people to an idea and a story about where they live. Like all brands, it is a shorthand of a promise of value. So the story has to have some connection with people’s lived experience of it.

But I think it’s trying to do something more. Cities are fragmenting, under pressure of money, climate, and the social, economic and generational consequences of these. Urban branding is trying to create a sense that shared place gives us something in common—from “me” to “we”, as the New York logo does. Of course: it might not be enough.

2: The ‘most significant’ political films

The New Republic decided that the summer was a good time to run a list of the Top 100 most significant political films, and invited the veteran film critic J. Hoberman to curate it. Hoberman suggested that it should be a list of “the most significant” rather than the best—which certainly makes it potentially more interesting. 79 critics, academics and film programmers each sent in their top 10 lists, and these were scored and ranked.

You can have a look at the list for yourself if you’re interested, but Hoberman’s essay on the exercise, about “what we learned” is worth a little time.

He gets through the obvious points quickly. Polls are about the people polled. Most of the 79 were based in North America, and North American films are well represented here. Although: the film that comes top (I’ve put in the footnote1) was written, directed, and scored by Italians about a conflict in North Africa, and in terms of votes was listed by almost half of the group and ended up miles clear of the second and third films in the list.

Some eras are more fraught than others. The oldest and the most recent films to make the Top 50 are Birth of a Nation (1915) and Selma, both really about the same subject, and both screened in their own times in the White House.

On Birth of a Nation, Hoberman has this to say:

Having demonstrated cinema’s power to rewrite the past, D.W. Griffith similarly proved that a film might intervene in history. Shown at the White House and endorsed by President Woodrow Wilson, The Birth of a Nation promoted the myth of the Lost Cause, falsified the history of Reconstruction, reactivated the Ku Klux Klan, and promoted a new national narrative based on Aryan birthright. It also inspired America’s first counter cinema, the “race movies” made by Oscar Micheaux and others.

Birth of a Nation comes fifth, one spot above Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. Younger critics were less likely to list it. They were also less fond of Eisenstein’s Potemkin, despite its high ranking here:

Younger voters were more militant, supporting The Hour of the Furnaces (#32), The Murder of Fred Hampton (#37), and Born in Flames (#43) in proportionally higher numbers.

His third opening observation is that there appeared to be broad agreement, if not consensus, about what constituted political cinema:

Over a dozen films in the Top 100 were about elections. Eight concerned the subject of revolution, over 10 depicted anti-democratic coups, and many more focused on political violence ranging from strikes and demonstrations to murder, genocide, and war.

Hoberman acknowledges that a list like this tends to the consensual—he tests this by asking a chatbot to do the same exercise. And he borrows Jacques Ellul’s idea of “sociological propaganda” to cover some of the familiar mainstream films in the list.

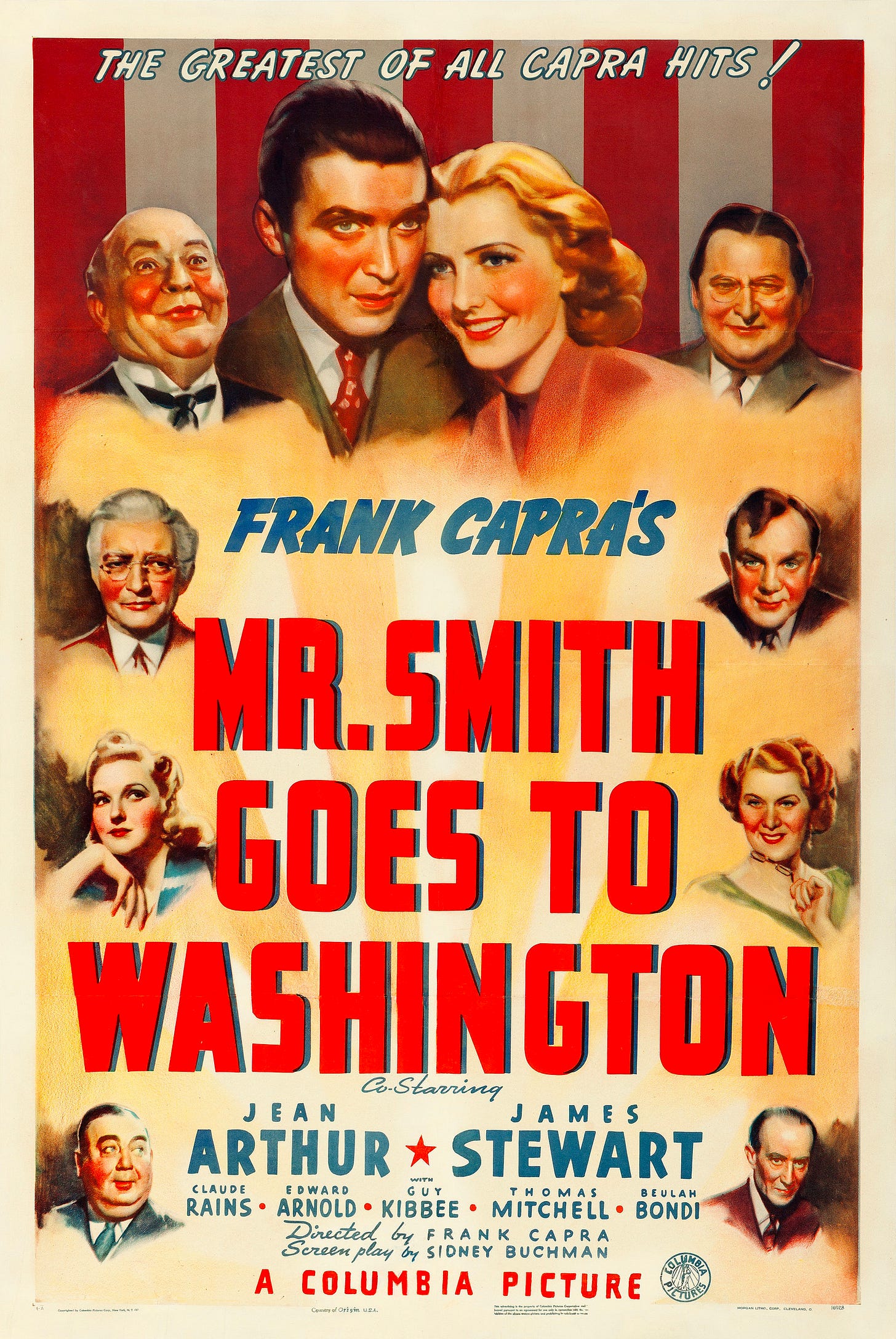

(‘One good man can make a difference’, and other feelgood political myths.)

The Frank Capra/James Stewart film Mr Smith Goes to Washington, for example:

The feel-good spectacle of James Stewart’s Boy Scout freshman senator filibustering a corrupt Congress to its senses may be Hollywood’s most resilient—and universal—political fantasy. Yes, the system works, and one good man can make a difference!

Or, more recently, All The President’s Men, which, he says, illustrates “Truth, Justice, and the American Way.”

He’s more interested in films that use multiple protagonists to portray a wider social conflict. Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing is an example of this, and polled well. There are other, non-American films in here in the same style:

Two more examples are The Lives of Others and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s 1968 Memories of Underdevelopment (#27), a newsreel-enriched portrait of a disaffected bourgeois in revolutionary Havana.

The definition of “political” also extends to how some of these films got made, drawing on a quote from Jean-Lus Godard:

“The problem is not to make political films but to make films politically.”

(Godard had six films nominated, but only two in the final list).

One of the things I like about Hoberman’s essay is that, as an educator as well as a critic, he goes out of his way to talk about films that the 79 critics have ignored or neglected—for example, Shinsuke Ogawa’s 1971 documentary, Narita: The Peasants of the Second Fortress , or a Carole Roussopoulos’ documentary portrait of sex workers occupying a French church— The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak.

In talking about these Godardian “politically-made” films, he mixes and matches:

Salt of the Earth was made by blacklisted Hollywood writers and directors, Chantal Akerman’s thirty-sixth-ranked Jeanne Dielman(1975) with an almost all-female crew, and Jafar Panahi’s unranked This Is Not a Film (2011) under a form of house arrest when he was forbidden to make movies. Plug pulled by its Hollywood studio, the 1974 anti-Vietnam War documentary Hearts and Minds (#39) was self-distributed, albeit by wealthy independents.

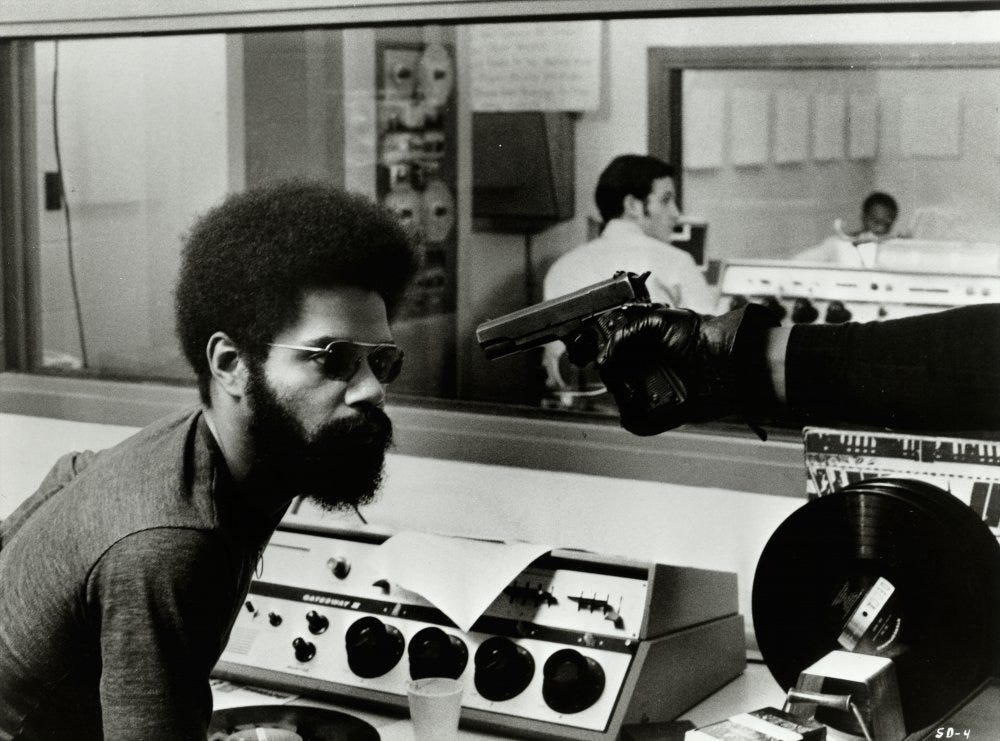

A film that does make the Top 100 list is The Spook Who Sat by the Door, produced by Sam Greenlee from his own novel. It was financed largely by Black investors and showed scenes of urban insurrection in which Gary, Indiana, stood in for Chicago:

Like Salt of the Earth, it was hounded by the FBI (with theaters subjected to intimidation), and like Hearts and Minds, it was abandoned by its distributor. Unlike either, however, The Spook Who Sat by the Door became a cult film, leading a fugitive existence circulating on bootleg VHS tapes.

(Still from ‘The Spook Who Sat By The Door’. Hounded by the FBI. Image: British Film Institute).

Finally, there’s a film made by the British director Peter Watkins for French television that I’d never heard of, but sounds fascinating. Watkins had made a faux-documentary, The War Game in the 1960s, about nuclear attack, which was financed by the BBC but shelved under government pressure for 20 years. His radical 1971 film Punishment Park, which is in here at #50, was set in an authoritarian Nixon-led America. His 1964 docudramaCulloden interviewed historical participants in the battle as if it was unfolding live in front of his cameras.

But I didn’t know that he’d been invited by French television to do something similar, much more recently, about the Paris Commune:

Nearly six hours long, made for but buried by French television, La Commune (Paris, 1871) integrates (space for) discussion within itself in its critique of the medium. Arguably the most original political film since Battleship Potemkin, if not The Birth of a Nation, La Commune is doubly pedagogical—made to educate its participants as well as its audience.

The film—#17 on the list—was shot in two weeks, in chronological order, after 16 months of pre-production, during which the characters—often played by political activists—had researched their own characters:

Actors merged with their characters as the events of 1871 reflected the situation of France in 2000.

Finally, he writes about the rise of hand-held phone-made films, or so-called ‘vernacular videos’:

As so-called guerrilla newsreels were facilitated by lightweight 16-millimeter and later video cameras, the development of the camera-phone in the early twenty-first century created a new sort of political cinema.

One critic put Zapruder’s famous 8-millimetre footage of Kennedy’s assassination on their list, although no-one put Darnella Frazier’s documentation of George Floyd’s death on theirs. Hoberman concludes:

There is a case to be made that, along with the various amateur recordings of the January 6 storming of Congress, Frazier’s 10-minute film belongs with the most significant political documentaries made in America over the past few years, if not ever. Because the personal really is the political.

j2t#470

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The Battle of Algiers, of course.