22 November 2022*. Update—Iran | Mastodon

Revolution from the bottom—Different by design—Notes from readers

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. This is update edition—shorter follow ups on recent pieces. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The roots of the Iranian protests

I wrote a piece about Iran here a few weeks ago, and more recently caught an interview with the Iranian-American academic Narjes Bajoghli on the podcast Politics Theory Other recently, and learnt quite a lot about the current Iranian protests that I hadn’t seen elsewhere.

Politics Theory Other podcast: https://on.soundcloud.com/Y8n6m

(‘Woman. Life Freedom’. Graphic by Farzan Kermaninjad, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

Some of this was about the present moment in Iranian politics, with a weak conservative President in power at least partly because the credibility of more liberal political leaders—who had been negotiating with the west to reduce sanction—had been destroyed by Trump’s decision to increase them. In turn the adverse effects of this on the Iranian economy had fallen disproportionately on women, who have been protesting about the hijab and other things since 2017.

Bajoghli suggested that one of the reasons that the protests have been so widespread is that almost everyone has had a brush with the Iranian morality police—even women in conservative households. And she had a wider point about the protests as well: that because the revolution that ousted the Shah in 1979 was a bottom-up revolution, people are used to the idea of protesting: the country hasn’t reached a political settlement that everyone is happy with since then.

Bajoghli also had a short article about the protests in Vanity Fair at the end of September. One of the things in that which caught my attention was the connection she made between younger activists, across the globe, connecting on various social media platforms, and a connection between the Iran protestors and a decade of other radical campaigns:

In the past five years, members of Generation Z have joined and added new energy to build popular uprisings against the fundamental structures that uphold those in power and that are endangering the planet. Each of these movements have given millennials and Gen Z new language and art for identifying structures of power: #OWS ushered in language for a critique of corporate capitalism and vast economic inequality; #BLM globalized the understanding that anti-Black violence is at the heart of the western project; #SaveSheikhJarrah laid bare the violence Palestinians live with on a daily basis and mainstreamed the notion of Israel as an apartheid, settler-colonial state; #MeToo and #NiUnaMás unmasked the fear and silence patriarchy demands for its continuation.

2: Mastodon and Twitter

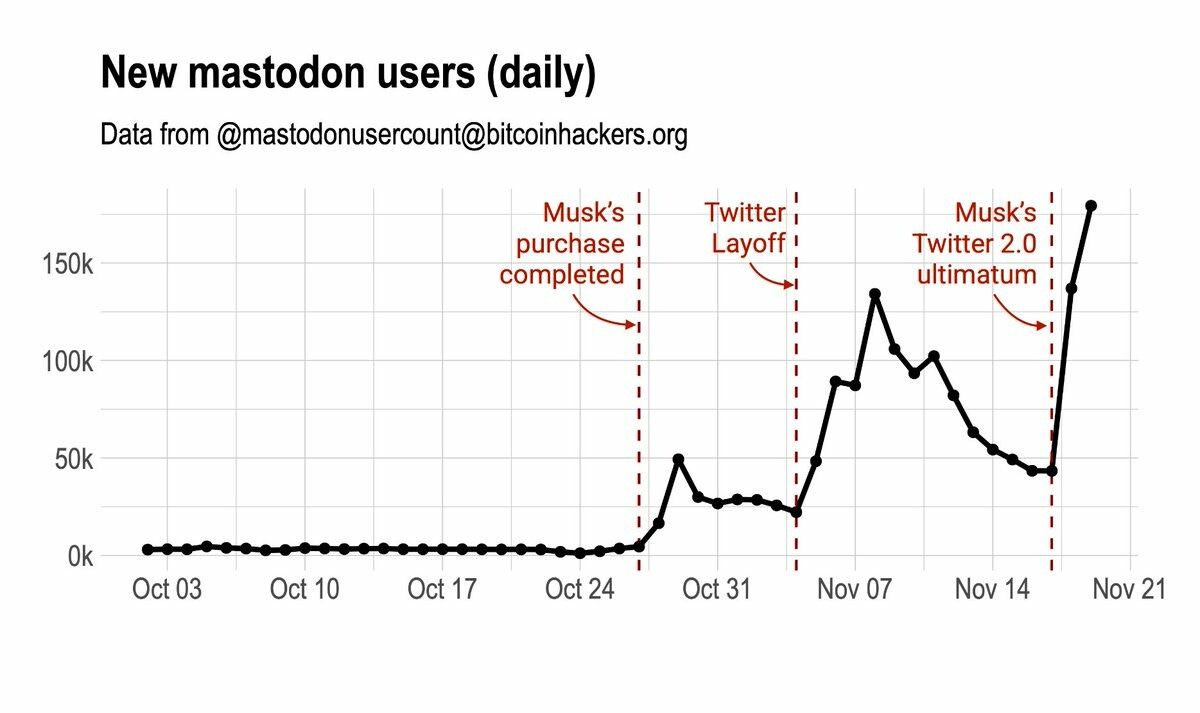

There was a telling chart on Mastodon at the weekend about the spikes of new joiners since Elon Musk took over Twitter. (I wrote about Mastodon last week).

The Markup editor Julia Angwin is one of those joiners, and in her interview at the weekend she talked to a friend and journalist, Adam Davidson, who had set up an “instance”—as Mastodon’s distributed servers are known—for journalists. Some of the conversation is about the way that Twitter’s verification “blue tick” effectively outsourced a set of journalistic decisions to Twitter, and—now that Musk has wrecked all of that—it was time for the journalism community to reclaim it.

He also underlines the differences between the two sites, driven by the way their design choices differ:

If I have a funny joke or a really powerful statement and I want lots of people to hear it, then Twitter’s way better for that right now... Whereas on Mastodon, it’s actually much harder to go viral. There’s no algorithm promoting tweets. It’s just the people you follow... I have something like 150,000 followers on Twitter, and I have something like 2,500 on Mastodon, but I have way more substantive conversations on Mastodon even though it’s a smaller audience. I think there’s both design choices that lead to this and also just the vibe of the place where even pointed disagreements are somehow more thoughtful and more respectful.

And I would have left this here, except that I saw that Mastodon.art had “defederated” from Davidson’s “instance”, journo.host, meaning that it had blocked anyone on journo.host from looking at any posts on Mastodon.art. (Which is a lovely place, by the way).

I’m not able to check the story out, but they said that people on the journalists’ instance had been using material without quoting it or paying for it, and had also been using a tool to find people that was designed to harass people. The Mastodon.art Curator: “using a tool developed by known harassers for the sole purpose of harassing is over the line.” There are some suggestions that Davidson’s put a stop to using this tool now, but for me this also speaks to the extractive nature of the relationships that social media has trained us to accept (it’s on Twitter so anyone can use it, right?).

(Image © by @twisteddoodles)

Notes from readers

Ellie Howcroft responded to my piece on ‘The Waste Land’ with a story about T.S. Eliot reading the poem to the British Royal Family at Windsor Castle during the Second World War, prompted by the writer and critic A.N. Wilson in an interview with Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother:

Elizabeth: “We had this rather lugubrious man in a suit, and he read a poem. . . . I think it was called ‘The Desert.’ And first the girls got the giggles, and then I did and then even the King.”

Wilson: “ ‘The Desert,’ ma’am? Are you sure it wasn’t called ‘The Waste Land?’ ”

Elizabeth: “That’s it. I’m afraid we all giggled. Such a gloomy man, looked as though he worked in a bank, and we didn’t understand a word.”

Wilson: “I believe he did once work in a bank.”

I couldn’t help but wonder if Eliot might have been trolling the Royals a little. Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats had been published in 1939, and he must have known that these poems would have played better than ‘The Waste Land’ with the extremely middlebrow Windsors.

j2t#396

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.