Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The cultural clues to Iran’s protests

I’ve been trying to understand the Iranian protests better, since much of the news coverage seems to be merely descriptive. The protests have erupted, as if from nowhere, after the death of a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Amini, at the hands of the Iranian ‘morality police’ for not following the country’s hijab regulations.

Of course, there’s lots to admire in the protests, such as the way that almost every photograph shows the faces of the theocrats that are the subject of the protests, and none of the protesters themselves. Hair, and its cutting and its combing, is also a visceral symbol that goes deep into our myths.

There’s some striking demographic data as well. Iranian fertility rates have plummeted to the point where it is barely above replacement rate (2.2 live births per woman), and the result of this should be a kind of ‘demographic dividend’.

Countries that go through this curve either find ways to use the human resource released by it (as Ireland did) or end up with unrest. Iran’s curve is far steeper, and so the impact will be greater. It’s perhaps not coincidence that Ireland’s equivalent curve, which started two decades earlier, also led to the end of the Catholic Church’s stranglehold on Irish life.

(Source: Worldometers)

It’s also a reminder that states take on women’s movements—even informal ones—at their peril, as the theocracy that controls the United States Supreme Court seems also to have discovered the hard way this year.

As Annabelle Sreberny, professor emeritus at the Iranian Studies Centre at Soas University of London, told the Guardian:

“The women’s movement in Iran started in the first month of the Islamic Republic and has been simmering for at least the last 20 years,” said Sreberny. “It is seen as a carrier of socially progressive values... many Iranians see the women’s movement as having the potential to be the next social force to make waves.”

And ‘Woman - Life - Freedom’ is a powerful slogan.

Looking back, hindsight suggests that the regime’s clampdown on the wearing of the hijab, which led to the arrest of Mahsa Amini, was an act the reflected political weakness, rather than strength. The ill-judged spat with CNN’s Iranian-British journalist Chritine Amanpour fits with this. She cancelled an interview in New York with Iran’s President rather than wear a headscarf, as he had demanded.

Following links, I ended up at the Twitter feed of the American-Iranian policy analyst Karim Sadjadpour, who suggested that the song ‘Baraye’, by Shervin Hajipour, held clues to what was going on. Since Hajipour had been arrested by the Iranian authorities, there’s clearly something happening here (there are English subtitles):

'Baraye’ means ‘because of’ in Farsi, and the lyrics of the song are a litany of reasons why people are protesting, assembled from tweets about why people are protesting against the death of Mahsa Amini. One version of the video unfolds the tweets as Hajipour sings.

The song went viral—crashing Iran’s social networks, by some accounts—and was watched 40 million times in two days, before the government found ways to shut it down. No matter: it’s being sung and played at protests inside and outside of the country.

The song underlines a generational issue as well. Iran’s median age is 32, but it is ruled by a gerontocracy. As we’ve seen in many countries across the globe, the young—connected to cultures of other young people across the world through social media—simply have different values to their older ruling elites.

And although I’m not trying to reach any strong conclusions here—I’ve been skating across this—there’s something interesting about the role of the large Iranian diaspora as well. Hyperallergic had an article that pulled together images by artists in support of the protests.

(Image: Zehra Doğan)

The Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan staged a performance outside the Iranian consulate in Berlin which involved spreading hair, henna, and menstrual blood on its gates (she was taken into custody and released later on).

> “Kurdish women in Iran are tortured both for their identity and because they are women … That’s why I practice my art with my hair and blood. I want to say ‘I am here,’ ‘we are here,’ with my femininity against the male state that oppresses women by holding them by their hair.”

Marjane Satrapi, who created the graphic novel Persepolis, did something a bit simpler:

Finally: Dezeen magazine also had a selection of artists’ images, mostly culled from Instagram. I liked this image by the Turkish cartoonist Oğuz Demir which played on the idea of combing unwanted objects (like insects?) out of your hair:

His caption: “You can't force people into your paradise”. A much, much, looser translation might be:

I’m going to brush those men right out of my hair.

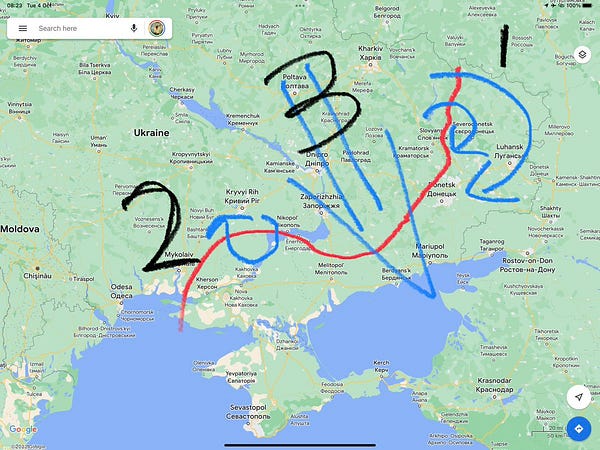

2: How wars end

How do wars end? At the end of the summer this seemed like an academic question, but suddenly it seems like it might be a real one, at least in the context of the Ukraine-Russian war. At least, if one assesses this against some of the more level-headed military analysts I follow on Twitter.

But it turns out that ending wars is maybe more complicated than this. The New Yorker turned to a group of academics who specialise in an admittedly niche discipline called ‘war termination theory’ to understand all of this better. And it is apparently a neglected area. A lot more work has been done on how wars start than how they end.

Hein Goemans, born in the Netherlands, who now works in the United States, wrote the first book on how wars end, published in 2000. Historically, the view was that one side surrendered, or was vanquished.

That already seems to be too simple a view. It takes two sides to start a war, and two sides to finish it. Russia abandoned the First World War after the Bolshevik Revolution, vanishing from the battlefield, but the Germans pursued them until they agreed peace terms.

Some of the early work on war termination borrowed concepts from economics: a war started when some kind of diplomatic bargaining process (over a piece of land, for example) broke down. War was a contest of strength, and the end of it was some kind of a bargain that resolved the dispute between the two sides as it became clearer who was the stronger.

That makes wars sound like a kind of informational mechanism, to establish the relative strength of the two sides.

But other mechanisms tended to get neglected in this account, especially ones that had less to do with economics:

One was the fact that contracts in the international system—in this case, peace deals—had little or no enforcement mechanism. If a country really wanted to break a deal, there was no court of arbitration to which the other party could appeal... This gave rise to the problem known as “credible commitment”: one reason wars might not end quickly is that one or both sides simply could not trust the other to honor any peace deal they reached.

This is the story, for example, behind the British decision to fight on in 1940, when some members of the government urged Churchill to come to some kind of agreement with the Nazis. This example comes from the work of Goemans’ colleague Dan Reiter:

the British fought on, because they knew that no deal with Nazi Germany could be trusted.

Another factor that had been ignored in the literature was domestic politics. It turns out that this depends on the type of government. Goemans built a database to assess this:

(D)emocrats tended to respond to the information delivered by the war and act accordingly... Dictators, because they had total control of their domestic audience, could also end wars when they needed to. After the first Gulf War, Saddam Hussein was such a leader; he simply killed anyone who criticized him. The trouble, Goemans found, lay with the leaders who were neither democrats nor dictators: because they were repressive, they often met with bad ends, but because they were not repressive enough, they had to think about public opinion and whether it was turning on them.

According to Goemans, Kaiser Wilhelm met with his war cabinet on 17 November 1914 and concluded that the war was unwinnable. They fought on for four more years.

Obviously we’re interested in this right now precisely because of the Russia-Ukraine war, and the writer of the article, Keith Gessen, asked his group of war termination theorists about the prospects for ending this war. (The conversations with his contributors started before the Kharkiv counter-offensive, and continued during it.).

They recognised some familiar aspects. The first was the miscalculation of the original attack (the Ukraine leadership would flee, and Ukraine collapse), which was a classic case of information asymmetry, based on poor information.

There’s a “credible commitment” problem, on both sides:

Russia claimed that it could not trust Ukraine to not become, in essence, a NATO state; Ukraine, for its part, had no reason to trust a Russian regime that had repeatedly broken promises and invaded it in February with no provocation.

And as Goemans notes, sometimes war generates the causes of war:

The revelations of Russian weakness and Ukrainian strength have buoyed the Ukrainian public; the discovery of the massacres of civilians at Bucha and now Izyum have enraged it. If once there was space in Ukrainian public opinion for concessions to Russia, that space has now closed.

Goemans also talked about the scale of the war—it’s effectively a European war, even if Ukraine is doing the fighting. That raises the stakes.

When Gessen started researching the piece, his theorists expected a protracted war:

None of the three main variables of war-termination theory—information, credible commitment, and domestic politics—had been resolved. Both sides still believed that they could win, and their distrust for each other was deepening by the day. As for domestic politics, Putin was exactly the sort of leader that Goemans had warned about.

As the Ukrainian Army regained territory across Kharkiv, the theorists got more worried. A collapse of Russian positions—of the kind that several military analysts are now anticipating—risked Russian escalation, up to and including a battlefield nuclear weapon. But winter might mean that both sides dig in once more for an extended conflict:

“People think it’s going to be over quickly, but, unfortunately, war doesn’t work like that,” (Goemans) said. But he also believes that Ukraine will resume its offensive in the spring, at which point the same dynamic and the same dangers will be back in play. “For a war to end,” Goemans said, “the minimum demands of at least one of the sides must change.” This is the first rule of war termination. And we have not yet reached a point where war aims have changed enough for a peace deal to be possible.

Reiter, for his part, doesn’t see a way to resolve the “credible commitment” issue. The Russian Federation isn’t likely to change its politics soon:

“You really don’t like to leave in place a country that is going to offer some kind of lingering threat,” he said. “However, sometimes that’s just the world you have to live in, because it’s just too costly to actually remove the threat completely.”

But Ukraine can make itself more defensible—what Reiter called a “military hedgehog”:

“Ukraine will look a lot different as a country and as a society than it did before the invasion.” It would look more like Israel, with high taxes, military spending, and lengthy mandatory military service. “But Ukraine is defensible,” Reiter said. “They’ve proven that.”

Goemans is less optimistic. His original work was on the First World War, and in 1917, facing defeat, Germany unleashed its U-boats to carry out “unlimited operations”. It was a “high variance” strategy—the hope was that Britain could be starved out of the war before the US entered it. It didn’t work.

For U-boats in 1917, read battlefield nuclear weapons now.

One of Goemans’ former students, Branislav Slantchev, is more persuaded than the others that Russia will use tactical nuclear weapons (meaning something less than a kiloton, or around a fifteenth the size of the Hiroshima bomb).

This could lead to yet another round of escalation. In such a situation, the West may be tempted, finally, to retreat. Slantchev urged them not to. “This is it now,” he wrote. “This is for all the marbles.”

It is perhaps, therefore, not coincidence that the retired American general David Petraeus has been on television this week saying that he thought that if Russia did use nuclear weapons, NATO would destroy the Black Sea fleet. People like Petraeus tend not to make off the cuff remarks on the morning shows. The stakes are high; this is for “all the marbles”.

As Goemans tells Gessen:

“This will shape the rest of the twenty-first century. If Russia loses, or it doesn’t get what it wants, it will be a different Russia afterward. If Russia wins, it will be a different Europe afterward.”

j2t#378

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.