22 March 2023. Farming | Cars

Maybe vertical farming isn’t so easy // Cars, urban visions, and unintended consequences

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Maybe vertical farming isn’t so easy

So: according to a story in Fast Company it’s possible that vertical farming is a “bubble” that is about to burst. (Thanks to my colleague Lewis Lloyd for the link). Vertical farming is indoor farming, often at multiple levels, on a smaller surface area than traditional farming. It’s been one of the futures of farming, as far as I can remember, for the last 15 years or so.

The benefits: much greater control of the food production process, and potentially more frequent yields. The downside: they need a lot of lighting, which means a lot of energy.

Anyway, the Fast Company article starts with the sad story of Fifth Season, a vertical farm in Pennsylvania, where workers arrived one morning to discover they’ve been laid off. (You gotta love American labour agreements):

The farm, which had opened two years earlier, seemed to be running smoothly, growing tens of thousands of pounds of lettuce per year inside a robot-filled 60,000-square-foot warehouse. The brand was selling salad kits—like a taco-themed version with the company’s baby romaine, plus guacamole, tortilla strips, and cheese—in more than 1,200 stores, including Whole Foods and Kroger. Earlier in the year, the company had said that it projected a 600% growth in sales in 2022... Solar panels and a new microgrid had recently been installed at the building. A larger farm was being planned for Columbus, Ohio. But the workday never started.

The staff were told the business was shutting immediately.

The article has a litany of other similar concerns about the sector:

AppHarvest, which runs high-tech greenhouses in Appalachia growing tomatoes and greens, said in a recent quarterly reportthat it had “substantial doubt about our ability to continue as a going concern” unless it could raise more money… Agricool, a French company growing greens in recycled shipping containers, went into receivership in January. Infarm, a vertical farming company based in Berlin, recently announced that it was laying off more than half of its workforce—500 workers. IronOx, which built a complex robotic system to run its indoor farms, laid off nearly half of its staff.

But let’s start with the benefits of the indoor farming model:

They often use 90% less water than traditional farms... Indoor farming also eliminates pesticides and reduces fertilizer and keeps it out of rivers. Lettuce grown near Boston or New York City can avoid traveling thousands of miles from Western fields, saving gas and staying fresh longer... And as climate change makes extreme heat, drought, and flooding more likely, growing inside could become a necessity for some crops.

(A vertical farm in Finland. Image: ifarm.fi. CC BY-SA 4.0)

So let’s imagine that there might be four hypotheses here. The first is that the way this model is being applied isn’t quite right, and it needs to be rethought. The second is that well-managed greenhouses are always going to out-compete vertical farms (because they are cheaper and use natural light). The third is that the food sector and venture capital aren’t a good mix.

These tend to get a bit tangled up with each other.

On hypothesis one, some of the vertical farms seem to have invested huge sums—perhaps more than a lettuce business can sustain. Lighting is expensive, and although renewables help, it takes five acres of solar panels to grow an acre of lettuce.

Some of the businesses have bet on being able to automate a lot of the growing processes, but have invested heavily in tech, often writing it themselves. One of the reasons for doing this is that Silicon Valley investors like those stories, even if they make little business sense in the food sector:

“There are many reasons why they’re doing it, but one of the reasons is because they know that Silicon Valley investors won’t invest in a farm, but they’ll invest in a tech company,” says Henry Gordon-Smith, founder of Agritecture, a firm that consults on urban farming projects.

Eric Stein, who runs a research centre, the nonprofit Center of Excellence for Indoor Agriculture, says the economics don’t add up:

“For the life of me, I do not understand why investors are investing, because the economics are not the same as Silicon Valley high tech,” says Stein. “No matter how you want to spin it, it’s not the same. If you can build a farm that has a nice, healthy 20% to 25% margin, that’s a good bet. But it’s not going to be 150%.”

As Stein points out, it takes a long time to recoup a $20 million tech investment on items that sell for $1 or $2 a time.

And the most recent AgFoods report points out that venture capital investment in the food sector has fallen pretty much across the board, probably for reasons that have nothing to do with the food sector and a lot to do with the problems of the VC sector.

The Dutch experience is relevant because it is one of the largest exporters of food in Europe, and almost of that has involved innovation in food production. The Fast Company article suggests that the Dutch model manages to get by on less of everything: less labour, less technology (even though use technology effectively).

As it happened I’d looked at a long Washington Post article on Dutch food innovation a few months ago. If there’s a story in there, it seems to be that the Dutch farms are also operating at a far larger scale, and that some of them mix the benefits of simpler greenhouse technology with some vertical farming techniques.

In the US, one of the responses to this has been to change the product mix towards more expensive products, although this may be coming at the problem the wrong way round, as pivots go. Berries, for example, produce better returns than greens, but are harder to grow:

Companies are also shifting to other types of produce that could potentially make more: Oishii, one startup, markets absurdly expensive strawberries—$20 for a tray of 11—with a unique flavor. One of the farms Plenty is opening after closing its South San Francisco facility is in Virginia, where it’s partnering with berry giant Driscoll to, it claims, grow 20 million pounds of strawberries a year, with the first crop expected next winter.

It seems likely that we’ll need new farming techniques as climate change continues to roll through our weather systems. It’s possible that these issues are just part of a learning curve. But it still raises an issue, which is that stupid investments by people who think that tech is going to, er, ‘disrupt’ food production colour the impression of new ways of growing. And in turn, this can discourage more sensible investors who actually understand that food isn’t a technology sector.

2: Cars, urban visions, and unintended consequences

In Monday’s Just Two Things I started this review of Tom Standage’s book A Brief History of Motion. In Part 2 I will look at the cultural shaping of the car-based city, and the long histories of innovation.

Positive futures

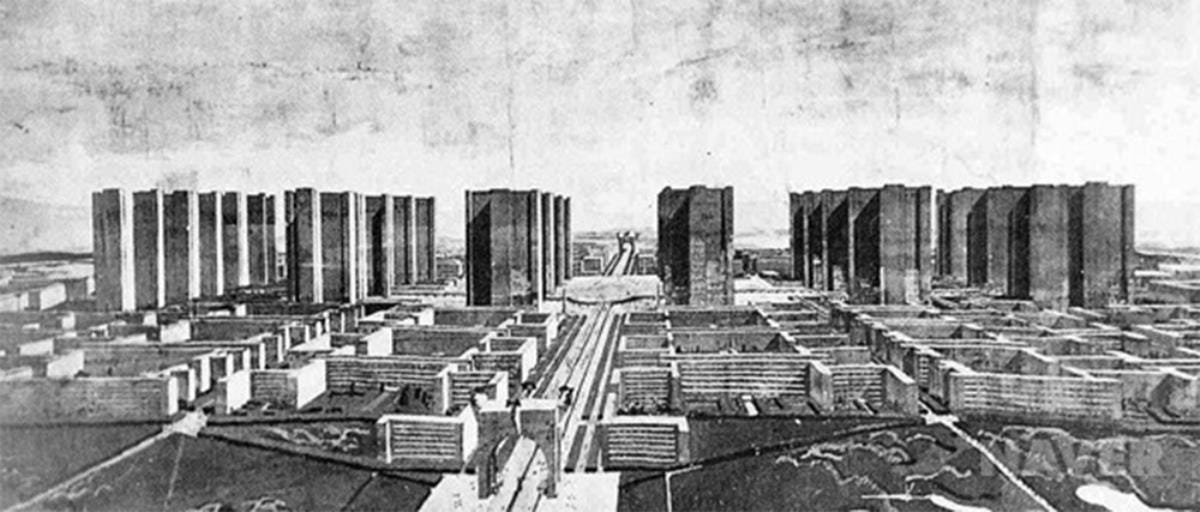

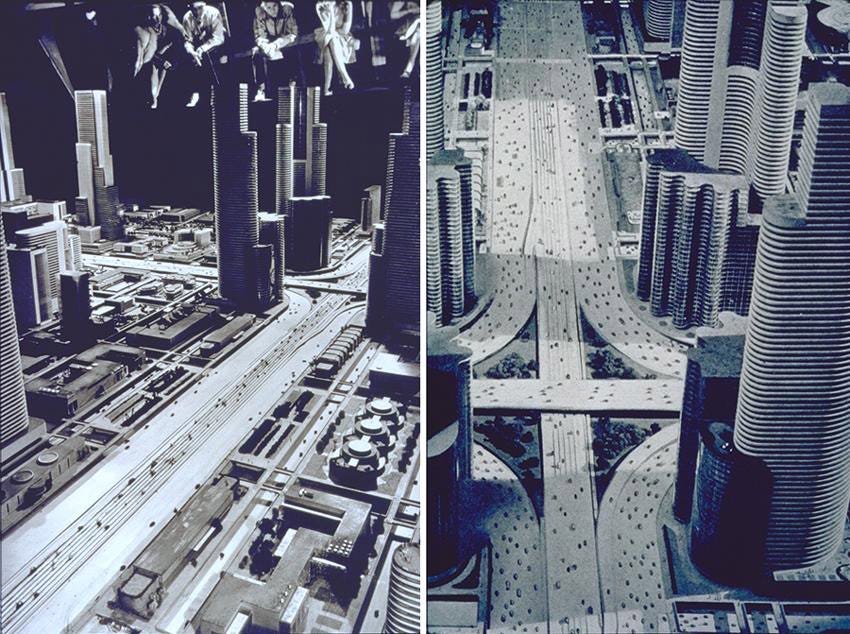

Images of the future with cars at the centre of them transformed the public discourse. The 1939 World’s Fair was a decisive moment in this. Its Futurama exhibit, sponsored by General Motors, showed a vision of a future city built around the car, which combined tightly zoned urban districts and car-dependent suburbs. The shadow of Le Corbusier’s 1920s design for the Radiant City—which separated cars and people—falls across these auto-utopian designs:

(Le Corbusier) declared that "streets are an obsolete notion" and that "normal biological speeds must never be forced into contact with the high speeds of modern vehicles." (118)

(Above: Le Corbusier’s La Ville Radieuse: Below: General Motors and Futurama)

The practice was less ideal.

The urban planner Robert Moses had been a prime mover behind the World’s Fair, and he set about building car-only ‘parkways’ across New York. (‘Parkways’—even the name.)

In the UK, the same imagined future, of urban motorways taking cars quickly in and out of city centres, also gripped the planners’ imagination. These projects were started in every large city during the 1960s, before being abandoned in the face of local opposition and changing values after some initial roads were built.

Long histories

Some of the contemporary futures of the car that we are offered have longer histories than we like to imagine. Uber’s model of using, effectively, private vehicles as hire cars, was foreshadowed by the jitneys that operated in their thousands in American cities in the 1910s. Eventually they were licensed out of existence. A similar idea emerged in Mongomery during the bus boycott in 1956, when car pooling helped black people get to work. This time, the courts shut them down.

Standage also notes that the idea of autonomous vehicles also has a long history. The roads in the 1939 Futurama exhibition were ‘magic motorways’ on which cars drove themselves. Its designer, Norman Bel Geddes, was sceptical about humans’ competence as drivers:

"Human nature itself, unaided, does not make for efficient driving”, he argued. "Human beings, even when at the wheel, are prone to talk, wave to their friends, make love, day dream, listen to the radio, stare at striking billboards, light cigarettes, take chances.” (184)

The modern evolution of the driverless car has striking similarities to the early days of the car itself. The blueprint for the early DARPA-sponsored competitions for the vehicles could have been lifted directly from Le Petit Journal’s Paris-Rouen race.

The very early technical improvements were rapid in both cases. But he notes that the AV prototypes are “stuck in perpetual testing”, while many of the predictions about autonomous vehicles also seem ‘eerily familiar’ to those made about early cars, which should of itself invite scepticism:

Automobiles were expected to be safer than horse-drawn vehicles because unlike horses they cold not bolt, kick people, or be scared by sudden noises. But because ofthie greater numbers and higher speeds, cars proved to be far more deadly... Similarly, cars were expected to reduce traffic congestion because they would take up less space on the road than horse-drawn vehicles. Again, the opposite proved to be the case. The lesson of the twentieth century is that when more road capacity is added to ease congestion, it encourages more car journeys. (198-199)

He quotes a San Francisco research project from 2017 that simulated the benefits of having a driverless car. It found that participants took more half as many additional trips, and those trips were also longer.

Roads not taken

Every story of a successful technology is also a story of technological lock-in. In telling his story about ‘jaywalking’ and pedestrian management, Standage also refers to the alternative path, in which conflicts over road use are instead resolved by reducing the impact of cars on pedestrians.

The road not taken here leads to Scandinavia and to Vision Zero. Both Helsinki and Oslo reported zero pedestrian road deaths in 2019; no children died in Norway in traffic collisions in the same year. The recipe includes lower speed limits, wider pavements, protected bike lanes, car free zones, and effective forms of road pricing:

Officials in Oslo talk of cars being treated as "guests" or "visitor, rather than owning the streets." Cars are not banned entirely, but drivers crawling through the city center are made to feel like interlopers. (106)

A similar lock-in happened around petrol. The early electric cars were clean, reliable, and mechanically simple, and looked promising, but battery technology didn’t improve enough to make it work. The first Ford Model-T was a “fuel flex vehicle” that could go on either ethanol or petrol. Ethanol had been widely used as a lighting fuel, so there was a distribution network for it. But the US tax regime wasn’t kind to it, and new oil finds pushed the price of petrol down.

--

Of course, all technologies reverse into the thing they are trying to escape from. Standage can’t find a record of the sometimes reported 19th century London Times’ prediction that its streets will be nine-feet deep in horse manure by 1950, if present trends continued, but there is plenty of published concern about the public health effects of using horses for transport. (Horse numbers in the US had grown fourfold between 1870 and 1900). Of course, cars create the same public health concerns now.

The French journalist Louis Baudry de Saunier could write in 1900 that “the automobile makes even the calmest man burn with an insatiable desire for speed”, but average urban speeds at the start of the 21st century were no faster than at the end of the 19th.

This is probably a theme of the book. Standage opens with an epigraph from Melvin Kranzberg:

Many of our technology-related problems arise because of the unforeseen consequences when apparently benign technologies are employed on a massive scale. (ix)

Standage himself draws three lessons from his book. The first is that it would be a mistake to replace one transport monoculture with another, as we did when we switched from horses to cars. The second is, channelling Kranzberg, that all technologies have unexpected effects:

The ways in which cars would transform aspects of everyday life, from mass production to dating to fast food to shopping malls, was entirely unanticipated. (214)

The third is that among those unintended consequences, the most damaging is the exhaust. At scale, horse manure had terrible effects on public health. The emissions from cars are bad for the health of people and planet.

Standage says, optimistically, that it’s almost as if we’re back at 1895 again, with the chance to make better choices for our cities. But the car, and its infrastructures and its business models, are now so locked in that it’s not as easy as that. We’re all stuck in the world that Alfred Sloan and Norman Bel Geddes created in the 1920s and the 1930s, whether we like it or not.

j2t#438

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague