20 March 2023. Cars | Textiles

Cars, conflict, and political capture. // Following the trail of ‘shoddy’ cloth

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Cars, conflict, and political capture

Part 1 of a two-part review of Tom Standage’s 2021 book A Brief History of Motion.

Although Tom Standage’s book is billed as A Brief History of Motion, it is really about the long century of the car. Standage dates this from 1894, when the French newspaper Le Petit Journal its first automobile race, from Paris to Rouen, and six years after Bertha Benz had climbed into her three wheeled Motorwagen with her teenaged sons and driven to see her mother, who lived sixty five miles (105 km) away.

I picked up Standage’s book in the library because I had enjoyed other of his books, notably The Victorian Internet, about the invention and use of the telegraph in the 19th century.

It takes him a couple of chapters to get up to speed, with a canter through various wheeled vehicles that preceded the car—chariot, cart, carriage, train, bicycle. I learned a few things from this.

There were civilisations that knew about the wheel but didn’t use it for transport, usually because the vehicle weight wrecked their tracks. The first public transport service in the world, in Nantes, in France, in 1926, gave us the word ‘omnibus’. The internet tropes about modern rail gauges being defined through a series of path-dependent outcomes from the Roman chariot don’t stand up to scrutiny. And the bicycle, which preceded the car, literally paved the way for the car, by improving road surfaces.

The book proceeds partly chronologically and partly thematically. Looking across the chapters, a few things jump out. The first is the amount of conflict around the car. The second is the extent to which car companies shaped regulation and policy in their favour. The third is the way that they used what would be now called ‘cultural imaginaries’ to shape ideas about desirable (car-based) futures. The fourth is that almost all of the recent innovations about the car have longer histories that is usually understood. And fifth, the role of lock-in and path dependency is critical, and hard to unwind.

Conflict

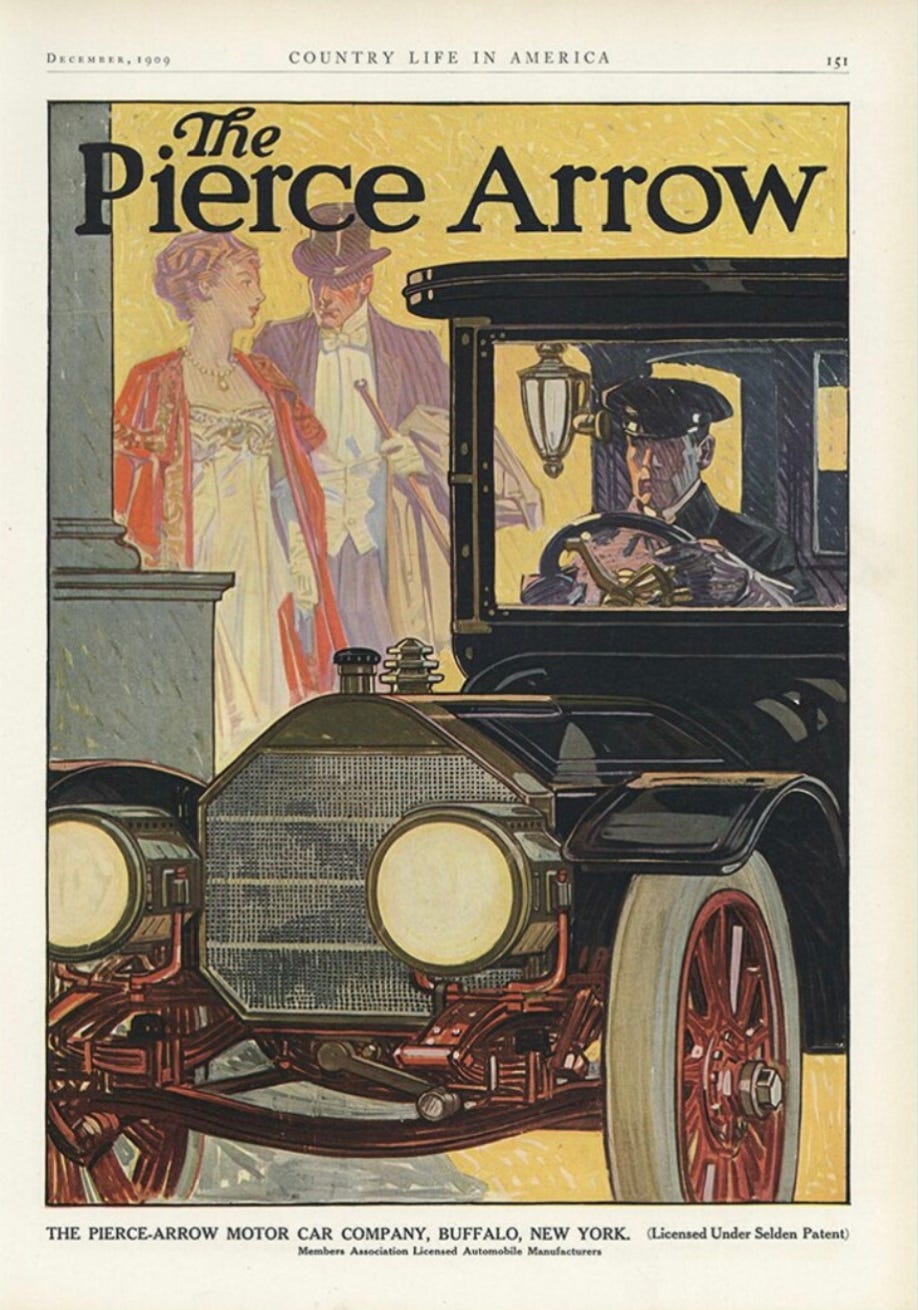

In 1900, there were around 8,000 cars on each side of the Atlantic. By 1908, these costs between $80,000 and $200,000 in current prices, but running costs were also high. Driving a car was a messy business and having a chauffeur certainly helped. In the US farmers would dig ditches to stop people driving through their area. The most famous early motorist in English literature is a reckless aristocrat, Toad of Toad Hall.

(A chaffeur helps. Pierce-Arrow advertising, 1910s. Via Etsy)

In other words, there’s a strong element of class conflict around the car in the 1910s. In 1906 Woodrow Wilson, then running Princeton,

worried that loutish motorists were fanning the flames of resentment towards the rich: “Nothing has spread socialistic feeling in this country more than the use of automobiles” (67).

This antagonism never completely went away. In the 1960s, when the ideological triumph of the car was at its height, Robert Moses’ New York road schemes were described by neighbourhood organisations as

white men’s roads through black men’s houses.

This conflict was reduced by two things. The first was the falling cost of the car, driven initially by Henry Ford, who combined process innovation and materials innovation to drive down the price of the vehicle. The second was the way in which General Motors, under Alfred Sloan, turned the car into an object of social status, pretty much inventing 20th century consumer capitalism at the same time. It segmented its consumers by income, used annual design updates to encourage people to buy more recent models, and locked its customers into finance deals to pay for them. It almost bankrupted Ford at the same time.

Capturing politicians and regulators

More cars meant more conflict with other road users. In the United States, the car companies manufactured the idea of ‘jaywalking’—to describe pedestrians who crossed roads in an unregulated way—and successfully pushed sanctions against ‘jaywalkers’ into city bylaws. (This part of the story was noted by every review of the book that I saw). Critically, this shifted the responsibility for road safety onto the pedestrian from the motorist.

In Britain, in 1937, a Parliamentary report on road safety took a similar tone:

Propaganda should be employed for the purpose of making those who do not own motor-cars realize how much they owe to motor transport for the supply of their food, for passenger services and so on. There still remains in the public mind a prejudice against motor-cars, born no doubt in the old days when few people owned them (103).

And in Germany in the 1930s, Hitler promoted the car as an engine of growth of the economy, removing regulations and taxes, and abolishing speed limits (which to this day don’t exist on German autobahns).

For me, this added a layer of further understanding to the Carlota Perez model of technological and financial innovation. She suggests that long technology surges, long S-curves which take 50-60 years, fall into two parts. There is an installation phase, funded by finance capital, and a deployment stage, funded by production capital, separated by a financial crash.

She doesn’t really discuss regulation, but in my work with her model, I have noticed that regulation to manage the external costs of a technology surge tends to arrive only in the fourth and final quadrant of the S-curve.

But it’s clear from the car story that there is a period in the second and third quadrants of the S-curve, when the technology is associated with the idea of ‘being modern’, when politicians and regulators align regulation for the benefit of the companies that are promoting the new technologies. We saw something similar with the ICT/digital surge, when regulators for a while went out of their way to make life easier for Big Tech, although now that surge is reaching its end regulators have become more focussed on reducing external costs.

And I’m just making this point here because the usual story about technological surges and regulation is that somehow politicians ‘get in the way of change’. That’s not right. They help it along.

(Part 2 on Wednesday)

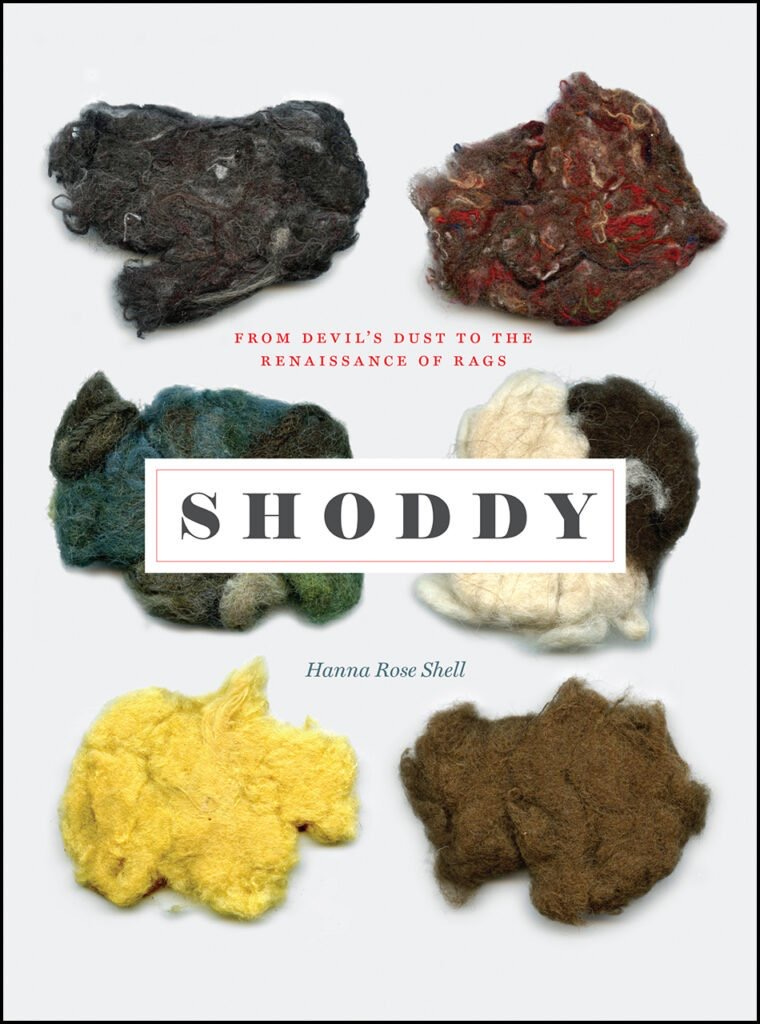

2: Following the trail of ‘shoddy’ cloth

For some reason a couple of pieces about what happens to old textiles have come my way recently. The first was an interview with the historian Hanna Rose Shell on the People and Things podcast on the history of ‘shoddy’—which was a noun before it became an adjective. The second was an interview on Scope of Work with Adam Minter, on what happens to goods from the Global North once they get donated to the charity shop or thrift store (there’s enough interesting material in this outside of the paywall to make it worth noticing).

Shoddy was the name for clothes and textiles made from old wool—it was unpicked and rewoven. It was always clothing for the poor, but there was still expertise in making it. All the same, as different parts of the world industrialised, shoddy tended to gravitate to the newer industrial locations. (I can’t remember who said that the history of textiles is also the history of capitalism, but this is also another example of that.)

Here’s an extract from a short review of her book:

The term came into existence in the early decades of the nineteenth century as a noun, referring to a new textile material produced from old rags and tailors’ clippings. Workers made it by shredding wool rags in what were christened “devils,” grinding machines equipped with sharp teeth. Recycled waste and other leftovers were turned into plentiful “new” raw materials in the “shoddy towns” of Batley and Dewsbury.

On the podcast she points out that the working conditions were terrible—one of the effects of the manufacturing process was to throw tiny wool particles into the air.

So the shoddy industry started initially in a particular part of West Yorkshire in England, and then migrated to the Northern states of the Union. Initially the clothes made from shoddy in the US went to clothe slaves, but when the Civil War broke out, the mill owners switched quickly to supplying clothes for Unionist soldiers, which often fell apart as they were wearing them. (She suggests in the podcast that this is when the word became an adjective meaning cheap and poorly made). They were’t particularly comfortable either: shoddy was often rough, rough, material.

In effect, Adam Minter takes up the story of how this industry works now in his book Secondhand, which looks at the contemporary global market for secondhand goods, including clothing.

The interview has a photo of a contemporary shoddy loom in Panipat in India, which is using shoddy to make blankets.

(A shoddy loom in Panipat. Panipat is the only region in India that is allowed to import used textiles. Image credit: (c) Adam Minter.)

Minter comes from a family that prospered in the US by recycling, and now works for Bloomberg, and he combines these perspectives by having some regard for the people who do the recycling, and some interest in the business models involved.

I think the narrative that's been established takes away agency from African and Chinese recyclers – it just says, you're dumping garbage on these people... It takes away their agency, it takes away their humanity. One of the things I wanted to do with this book was to say, look, these are not helpless natives, as they’re commonly depicted – they are business people who are doing things for themselves, for their families, for their towns.

His book looks beyond the textiles sector to other forms of second-hand goods such as electronics, but he points out that when you look at the shipping documents, the cost of shipping is being picked up by the importers in Ghana or Pakistan. In other words, there’s a business here.

And he points out that some of the issues here are about who gets to decide what waste is:

One of the underlying themes in this book is who gets to define what is waste. Right now, the way that treaties, legislation, regulations, and narratives are being written, it's really Europeans and North Americans who are deciding what is waste and telling the rest of the world to follow our definition.

Minter’s interest in the subject of the flows of secondhand goods started after his mother died, and he and his sister spent a year sorting out her possessions. That meant, eventually, going to a Goodwill (charity shop) store in the US.

I didn't expect the level of sophistication of sorting that you find at a Goodwill... There'll be large carts full of clothing and they will go to sorters who, first of all, ... have almost like a flowchart. ... I think it's around 85 to 90 brands on there. And they will tell the sorters how to price those. But on top of that, they go through and they feel the fabric. Is it thin? Does it feel like something that's gonna fall apart after one to five washes? ... There's an objective side to it. But there's also sort of the subjective side that requires the sorters in these rooms — just talking about apparel — to use their subjective knowledge that they've acquired as they spend time with thousands and thousands of garments.

Of course, there’s too much stuff, too much of everything. Most of the impact is in manufacturing, but the longer you make it last, the less impact it has. ‘Shoddy’ may have got a bad reputation, but in the UK, it is still used to fill mattresses. It is a form of downcycling, but it’s delaying the moment wool ends up in or on the land somewhere.

Other writing: music

The last of my series on Salut! Live looking back at the Celtic Connections festival in Glasgow has just been published, about the American band Bonny Light Horseman. Here’s an extract:

The(ir) first record is beguiling, a reworking of many of the classics of British folk music through a rich patina of Americana, as if The Band and Sandy Denny had got together and spawned a wild, self-taught, child. The name of the band is a clue to that—the song Bonny Light Horseman is a folk standard, which, slightly recursively, is also the first song on that first record, also called Bonny Light Horseman. On stage you can see why the band works. Mitchell and Johnson do most of the singing, and their voices meld well. Hers is high, quite gentle, and entirely distinctive, his a stronger tenor. On many of the songs they play to this strength, with his voice coming in behind hers, on a chorus or for a new verse.

The whole series is here. And here’s the band playing the folk standard ‘Bonny Light Horseman’:

j2t#437

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.