2 September 2023. Biodiversity | Identity

Even small areas of meadow have surprisingly big effects. // Identity, family, state: reading Kamila Shamsie’s novel Home Fire. [#492]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Even small areas of meadow have big biodiversity effects

John Naughton’s excellent Memex 1.1 blog pointed me to a small but interesting story about King’s College, Cambridge, turning over part of its lawns to meadow to improve biodiversity.

(The King's College wildflower meadow. Credit: Geoff Moggridge/King's College, Cambridge)

Small because it wasn’t a large area of land (around half a football pitch, between the college chapel and the river); interesting because the effects were disproportionately large. We know this because a King’s botanist, Cicely Marshall surveyed it before and after. The results are written up in Scientific American.

(Sensor design. Source: “Urban Wildflower Meadow Planting for Biodiversity, Climate and Society: An Evaluation at King’s College, Cambridge,” by Cicely A. M. Marshall et al., in Ecological Solutions and Evidence, Vol. 4; May 2023.)

The lawn became popular in England in the 18th century as a display of wealth—I’m guessing that it was associated with the landscaping and gardening boom that made people like Capability Brown rich and famous.

They come with environmental and financial costs:

They require far more water than similar-size meadows, especially in arid regions. Lawn grass is often overloaded with fertilizers and pesticides and is regularly clipped with gas-guzzling mowers . Meadows, in contrast, sequester more carbon than lawns and foster far more biodiversity.

Given its relatively small size, the researchers were curious as to its impact. But the answer is: lots.

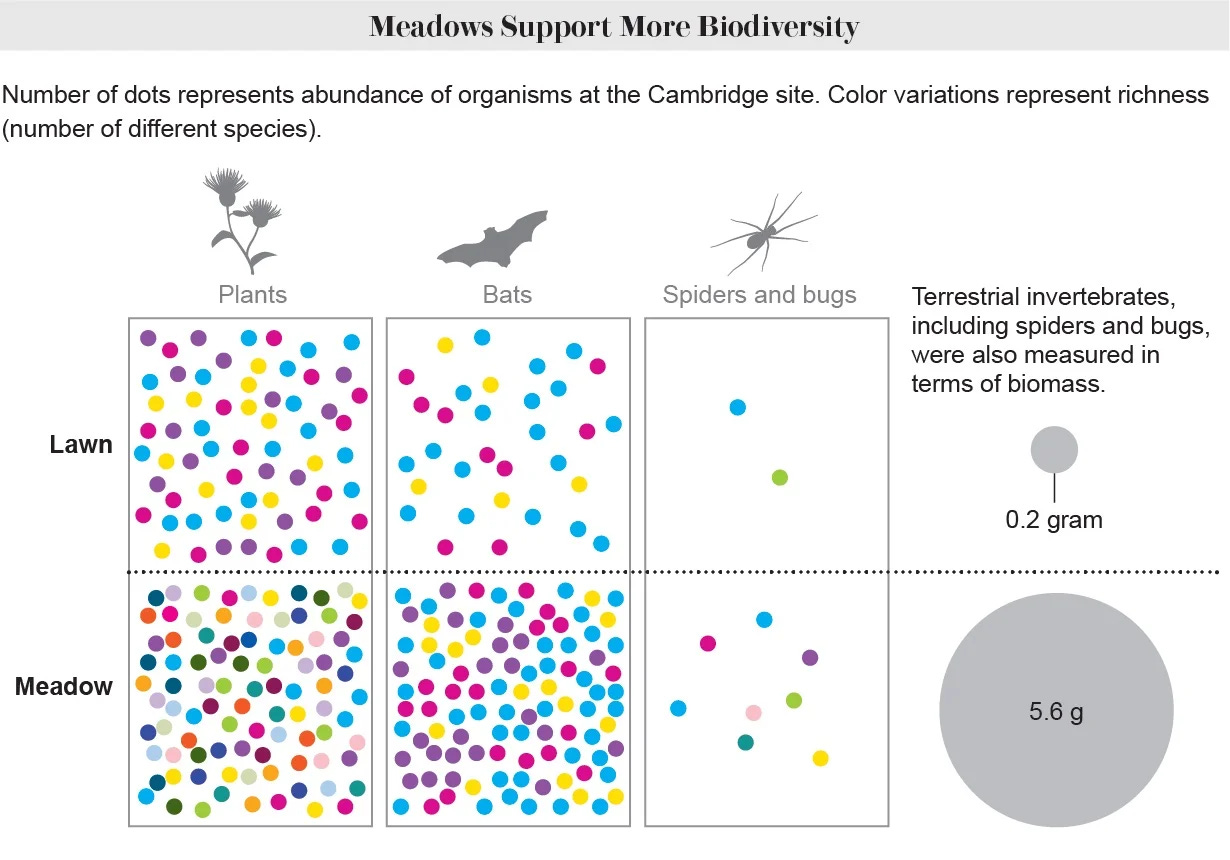

(Marshall) and her colleagues found that, compared with their numbers in the remaining lawn, plants, bats, spiders, true bugs and other invertebrates had flourished in the meadow. And without the need for much mowing or any fertilizer, the meadow's upkeep led to 99 percent less greenhouse gas emissions per hectare than the lawn.

The article comes with a terrific graphic showing biodiversity before, when it was lawn, and after, when it became meadow.

(Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Urban Wildflower Meadow Planting for Biodiversity, Climate and Society: An Evaluation at King’s College, Cambridge,” by Cicely A. M. Marshall et al., in Ecological Solutions and Evidence, Vol. 4; May 2023. Via Scientific American)

It seemed like there might be a bit more to the story than in Scientific American’s brief account. So I went into the weeds a bit1, and found that the journal article was outside of the Wiley paywall, as well as a write up on the university site. The journal article has an intriguing history of the area between the college buildings and the river—“The Backs”, as it is known:

in 1574, the college and city lands west of the river now known as ‘the Backs’ was a simple landscape of unimproved marshy pasture, which by 1592 had been formalised with avenues of trees, an artificial pond, and a duck house. In place of the King's Back Lawn were an orchard, a bowling green and a fellows' garden, which were replaced in 1688 with a grass sward divided by paths and avenues of trees... Not until 1772 did the idea to improve the land between Gibbs and the river take shape; the tree lined avenues were removed and the whole area was laid out as lawn to form the ‘Great Square’ of grass, known today as the Back Lawn.

The lawn was turned over to meadow in late 2019 on the initiative of the King’s College head gardener, Steve Coghill, and a King’s academic, Geoff Moggridge. Coghill describes it as

essentially an East Anglian hay meadow in the centre of Cambridge.

The Cambridge University article has more detail about the improvements in biodiversity, as well as other effects of the small meadow.

Despite its size, the wildflower meadow supported three times more species of plants, spiders and bugs than the remaining lawn - including 14 species with conservation designations, compared with six in the lawn. 84 plant species were counted during the sampling – but only 33 of these had been sown, with the rest appearing naturally.

In other words, meadows, once they develop, create their own biodiversty.

Also recorded were 16 bug and spider species, 149 nematode (roundworm) genera, and 8 species of bat. “We found that bats are foraging three times more often over the meadow than over the lawn. For species that might look for insects over several miles in a single evening, it’s incredible that our small meadow impacted their behaviour,” says Marshall.

There are also direct climate effects.

The reduced mowing and fertilisation associated with the meadow was found to save an estimated 1.36 tonnes of carbon emissions per hectare per year when compared with lawn... The meadow was found to have another climate benefit: it reflected 25% more sunlight than the lawn, helping to counteract what’s known as the ‘urban heat island’ effect.

The emissions numbers aren’t huge—that’s less than a return transatlantic flight—but these difference is likely to get larger. Lawns are becoming harder to maintain in the south of England as the climate becomes drier, to the point where many of Cambridge’s college lawns died out and had to be replanted last year. Wildflowers, in contrast, have deeper roots and are therefore more resilient to drought.

Finally, the researchers also surveyed respondents to test attitudes towards more meadow. The results were “overwhelmingly” positive, talking about the benefits to mental wellbeing, the environment, and educational value.

But they also said that lawns were important for recreational purposes.

Steve Coghill is also interesting on the cultural load that comes with lawns, perhaps a legacy of their origins as displays of landed money in the 18th century:

Many people mow their lawns because that’s what they’ve always done. There’s a perception that a close-mown lawn demonstrates you’re caring for the garden more.

Marshall et al’s full academic article is online at Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

2: ‘The ones we love… are enemies of the state’

I originally picked up Kamila Shamsie’s 2017 novel Home Fire because I was intrigued by the idea of using Antigone as a way in to the modern politics of race, state, and identity.

It took me a couple of goes to start it. The opening scene, in which Isma is interrogated by British border guards before she is allowed to fly to America, is important to the plot, it turns out, but was claustrophobic the first time I tried to raed it.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-SA-NC 4.0)

When Isma reaches the US, the story opens out, in multiple ways. I’m not going to say too much about the plot, because spoilers, but let me try to sketch in enough to indicate the lines of the story.

The novel unfolds in four parts, each focussing on one of the four main characters. Isma Pasha is the older sister to the twins Aneeka and Parvaiz, and has effectively brought them up after the early death of their mother. Isma is clever but plain, while Aneeka is smart and also clearly drop dead gorgeous. Parvaiz is fascinated by sound recording, and is trying to get work doing it. The twins are close, very close. I should add, because it is relevant to the story, that they are observing Muslims.

The fourth character, Eamonn, has Pakistani heritage, but has never visited the country. ‘Eamonn’ is a homophone of the Pakistani name ‘Ayman’, which is a telling detail. His wealthy father, Karamat Lone, married to a successful Swedish businesswoman, becomes British Home Secretary (Interior Minister) early in the book.

Karamat is a recognisable type, more conservative than the Conservatives on immigration, urging others with his heritage not to stand out, not to be different. Early in the novel Karamat makes a speech at his old school in Bradford that sets out some of these lines:

There is nothing this country won't allow you to achieve - Olympic medals, captaincy of the cricket team, pop stardom, reality TV crowns... You are, we are, British. Britain accepts this. So do most of you. But for those of you who are in some doubt about it, let me say this: don't set yourselves apart in the way you dress, the way you think, the outdated codes of behaviour you cling to, the ideologies to which you attach your loyalties.

This is, to a significant extent, a story about fathers and sons, and about present fathers and absent fathers. We discover quite early in the story (slight spoilers) that the Pashas father was largely absent, a jihadi who who was captured in Afghanistan, imprisoned (and possibly “interrogated”) in Bagram, and died in transit to Guantanamo.

Some of things I liked about the book:

The portrayal of the way in which Parvaiz is (so-called) “radicalised”, which undercuts many of the assumptions made in the British mainstream about how or why people get enrolled in jihadi. Indeed, all of the cliches of “radicalisation” are parodied by one of Eamonn’s white English friends. It’s hard to read the section about Parvaiz without thinking—indirectly—of the way in which Shamima Begum, who was effectively groomed and trafficked for sex as a child, has been treated by the British state. (The book was published before her case, but there are elements of the novel that have become more contemporary since then.) Or that this hard line increases resentment and “radicalisation”, and so is counterproductive.

Similarly the sympathetic portrayal of Karamat Lone, Eamonn’s father, who could in other hands have become a caricature. I liked in particular a speech to his son about the family of his former girlfriend Alice:

I have a lot more trouble with all the Double-Barrelled girls whose fathers don't waste a minute telling me of their family's long association with India - governor of this Province, aide-de-camp to that Viceroy. Helped quell the Mutiny. Helped quell the Mutiny! All delivered in a way that sounds perfectly polite, but everyone knows I'm being informed that my son isn't good enough for their daughter?

The way the book manages to make Islam mundane, even familiar in some ways. For example, one morning after Aneeka has done her morning prayers:

‘What were you praying for?' he asked, when she came back in and started to unbutton her long-sleeved shirt, starting at the base of her neck.

'Prayer isn't about transaction, Mr Capitalist. It's about starting the day right?’

(I’ve written about this before in the context of G. Willow Wilson’s novel Alif The Unseen.)

A little later on there is a scene that makes a hijab seem sexy that I think only a woman could write.

The class differences in the book are as telling as the story about identity. Isma and her siblings are brought up in Preston Road, a shabby London suburb on the wrong side of Wembley. Eamonn’s life moves between the more fashionable and more expensive parts of west London, from Holland Park to Notting Hill to Brook Green.

The bits of Englishness in the book aren’t attractive, and they are sometimes subtly mocked. All the way through, in fact, positions and attitudes are set up and then undermined. Anyway, Eamonn is invited in to watch some cricket by his Iranian neighbour, who by my calculations came to the UK after the fall of the Shah. He taught himself about cricket when he came to the country as a way to understand the English. As he says to Eamonn:

When I first arrived in England as a student I decided I had to understand cricket in order to come to grips with the subtlety of English character, Mr Rahimi said, ushering Eamonn into the TV room... 'Then I encountered the figure of Ian Botham and discovered that the English aren't nearly as subtle as they want the world to believe. You Pakistanis, on the other hand, with your leg glances and your googlies.?

You don’t have to know anything about Antigone to enjoy the book, but this does give a pointer to the tone of the book. Indeed, there is an epigraph that is taken from Heaney’s translation:

The ones we love... are enemies of the state.

Without giving anything away, I’d say that it ends in the only way it could while being honest with itself. This time around, I finished it in less than two days. But it’s going to stay with me for a long time.

j2t#492

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Pun intended

Loved this Just Two Things. Another minor addition to the King’s meadow story is that King’s are sharing the seeds generated by the meadow with local schools. So that glorious meadow is creating many more.