1st November 2022. Cities | China

How Google’s Sidewalk Labs got the ‘smart city’ so wrong. // China, America, and peak globalisation.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: How Google’s Sidewalk Labs got the ‘smart city’ so wrong.

Google’s foray into Toronto—mentioned briefly on Just Two Things a while ago—was one of the worst things that could have happened to the idea of the “smart city”. So it’s not surprising, perhaps, that a Toronto-based journalist, Josh O’Kane, has now written a book on Google’s ill-considered Sidewalk Labs project, which he also covered at the time.

Next City has published an extract from the book, and it’s full of details that explain how Google managed to get the city so wrong. It started from the top:

By the start of 2016, (Google’s then CEO Larry) Page had made it clear to the employees of his Google side-project that they should think about the pieces of a city in wholly new terms. Every piece, every unit, could be movable or rearrangeable. They shouldn’t be restrained by governments, real estate prices or people—they should abide only by the constraints of physics.

Sidewalk Labs’ CEO Dan Doctoroff had worked on New York’s Olympic bid in the 1990s, and one of his mental models was the “bid book” that detailed how a bidding city would be transformed by the Olympics. The Sidewalk Labs team set out to build a bid book of their own—the so-called ‘Yellow Book’:

Peppered with references to Disney and the dome-obsessed futurist Buckminster Fuller, the Yellow Book declared that Sidewalk would help cities “overcome cynicism about the future” and build “a city from the internet up.” The plans proposed a massive community that could house 100,000 people across 1,000 acres. It viewed people through the lenses of efficiency and profit, even as it promised residents better lives through novel technologies.

Buried inside of the Yellow Book was a set of assumptions about how this suburb would work that were, frankly, dystopian. To be sure, there were some socially progressive ideas. Schools would account for different learning styles and even social disadvantage. The justice programme would transfer people from prison to mental health programmes, or substance abuse treatment. But, but, but:

Though Sidewalk promised to build an inclusive world, it proposed handing enormous power to the private sector. It would resemble a kind of fiefdom—one where people would be monitored from the moment they looked in the mirror in the morning. No, really. The mirror would collect data on residents using a hidden sensor to monitor for stress marks on a person’s face or changes in skin colour that could indicate fluctuations in blood oxygen levels.

The technology to do this wasn’t quite there yet, although all the bits were there. But sitting behind this was a more insidious notion: the Google city was a vast profit centre, trading in data:

Users would be encouraged to share as much data about themselves as possible, collected by everything from those smart mirrors to their smartphones. Project Sidewalk would create “a new market for data” to learn more about city living, and Sidewalk and other companies would reap economic rewards from learning about people’s day-to-day lives. Insurance company executives, for example, would trip over themselves for the type of smart-mirror data Sidewalk wanted to collect.

Of course, this is exactly the sort of urban innovation that you’d expect to come from a company that is steeped in Silicon Valley culture. They were disdainful, naturally, of urban bureaucracy, which they thought got in the way. Data could do some of these things instead:

(P)eople living in a Project Sidewalk community would also have to endure tiered access to their own neighborhood based in large part on how much data about themselves they were willing to share. In this regard, data would be a kind of currency: People who chose not to share anything about themselves when they visited a friend’s apartment in Project Sidewalk might not get access to its self-driving “taxibots” or be able to buy items from certain stores. Data could ultimately be used to reward “good behaviour,” too. Business licences could be more easily renewed for those offering good customer service. Interest rates on loans could be determined by “digital reputation ratings.”

Some readers might recognise this as looking quite a lot like Cory Doctorow’s notion of ‘Whuffie’, a reputational currency that pops up in his early novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom. All the same, it’s almost as if they haven’t read to the end of the novel, where the whole thing falls apart.

(The site of the planned Sidewalk Labs project in Toronto. Image booledozer, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.)

There’s also a telling story about Sidewalk Labs blindness to the building blocks of community in actually existing cities. The technology writer and urban innovator Anthony Townsend ended up at Sidewalk Labs on the back of his book Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia. Before Toronto, the company had been looking at whether it might be possible to buy a chunk of Detroit to develop their city. They’d found an area of the city, Poletown East, which seemed to be 85% empty: it would, they thought, sure be possible to persuade the other 15% to move out.

So Townsend was studying Poletown East on GoogleEarth when he noticed that the area still had a lot of churches, which seemed to be in good order. Some were black churches, some Polish. It turned out that congregations still returned to these churches:

These were people’s spiritual sanctuaries. Even though thousands had left the community, many still returned weekly to the place they once called home. Townsend was stunned—not because of the controversy that would clearly emerge if Sidewalk tried to displace the churches, but because no one at Sidewalk had raised this as an issue. They hadn’t considered how real people might be hurt by the utopian city they were planning to satisfy their billionaire patron.

2: China, America and peak globalisation

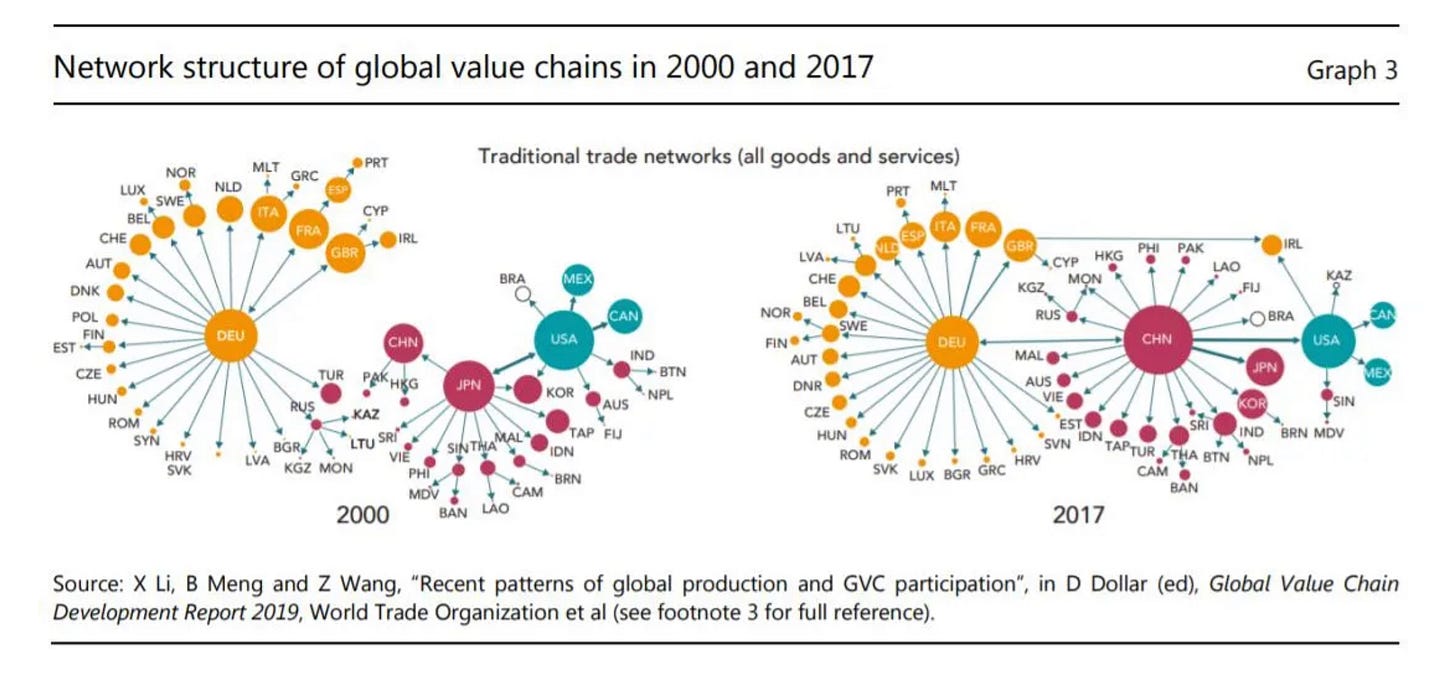

I saw a striking chart last week—I seem to have lost the immediate source for the moment—which showed global trade connections in 2000 and then again in 2018. The pattern was clear: in particular, over that time, China had been enrolled into the world economy, with strong links to both America and to Germany that hadn’t been there less than two decades earlier.

Of course, this is topical right now because the Biden administration is determinedly unravelling some of this right now, imposing controls that restrict exports to the Chinese chip industry. There’s a good piece by Jon Bateman at Foresigh Affairs that looks at this through the lens of US policy:

In short, America’s restrictionists—zero-sum thinkers who urgently want to accelerate technological decoupling—have won the strategy debate inside the Biden administration. More cautious voices—technocrats and centrists who advocate incremental curbs on select aspects of China’s tech ties—have lost. This shift portends even harsher U.S. measures to come, not only in advanced computing but also in other sectors (like biotech, manufacturing, and finance) deemed strategic... China’s technological rise will be slowed at any price.

I’m reading this as a sign that globalisation has peaked: the talk is now of a regionalised world economy, as Rana Foorohar writes in an edition of the FT’s newsletter Swamp Notes, which has been briefly released from behind the FT paywall:

If we had any doubt about US-China tech decoupling, the past few days have cleared it up... Regionalisation of the global economy gained further steam as French president Emmanuel Macron took the opportunity to call for a Buy European Act “like the Americans”, as the EU needs “to reserve (our subsidies) for our European manufacturers”. I’m actually OK with that; I think the world would ultimately be an economically healthier and more politically balanced place if there were more regionalised and even localised hubs of production and consumption.

From a Chinese perspective, it’s possible that Xi Jinping’s are also causing nervousness, at least among the rich. That’s what the Chinese stock market might be telling us, anyway:

(D)uring last week’s market rout, both foreign and domestic investors in China dumped a lot of short-term risk assets, but foreign fixed-income investors didn’t give up as many longer-dated Chinese bonds, while domestic investors dumped nearly everything. What does this tell us? For starters, richer Chinese are scared about the more authoritarian, top-down nature of President Xi Jinping’s regime. They are running for the hills.

Foroohar outlines a pessimistic scenario, and a more optimistic one. The pessimistic one sees the Chinese property bubble continue to deflate, with potential financial risk for the country’s provincial governments. If their debt turns bad it could be contagious: quite a lot of the Belt and Road programme is based on infrastructure funded by debt now against eventual returns later.

Well, I’ve read quite a lot of pessimistic accounts of the Chinese economy over the years, and so far they haven’t come to pass. So it’s probably worth sharing her more optimistic scenario as well:

China makes it through this period of turmoil, manages a kind of “soft” decoupling with the US (with lots of exemptions for various products) and then leverages the speed of decision-making inherent in authoritarian regimes to bolster its own technology needs and ultimately achieve regional supply chain independence. In this paradigm, more state control creates an executive, outcome-oriented system, well positioned to carry out a playbook for known economic needs.

There’s more to be written on China of course, though not today. Western commentators tend to see Xi Jinping’s assault on the big tech companies as catastrophic, although this assumes that huge tech companies are good for economies, and we haven’t seen much evidence of that in the West. At the same time, China is giving up some of the lower-value production it used to do to other parts of Asia, which is an inevitable part of growing richer, but the US squeeze on the high-tech sector may slow the development of its higher value production economy.

Swamp Notes is structured as a kind of conversation between Foroohar and her FT colleague, Edward Luce. As it happens, he doesn’t have much of a view on China, but does have a view on India:

(T)his is India’s chance to take the lead as the world’s fastest growing economy (a feat it did achieve once before, between 2013 and 2018). India has already taken a piece of the rejigged tech supply chains that are moving out of China... It has a much younger age profile than China, which is hitting a demographic middle-income trap. It has a far more impressive entrepreneurial base... While Xi continues to impose stifling zero-Covid restrictions on much of China, India is operating as if the pandemic is in the past.

But of course, people have also said this of India before, and been disappointed. And there are lots of reasons to believe that India can mess up this opportunity.

They include: its exposure to catastrophic climate change (up to and including ‘wet-bulb’ temperature); a shaky current account, given world energy and food prices; and its politics, which Luce describes as “ever more neo-fascist”—undermining the secular pluralism that had been a strength.

j2t#388

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.