Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Giving up on ‘smart’ cities

The idea of the ‘smart city’ was always something of a marketing pitch. There’s a reason why it was promoted aggressively by the likes of Cisco, IBM, and Siemens. It plugged into a 2000s idea of modernity at a time when city budgets were also tightening. They promised to collect more data, and use it to promote greater efficiency, at lower cost.

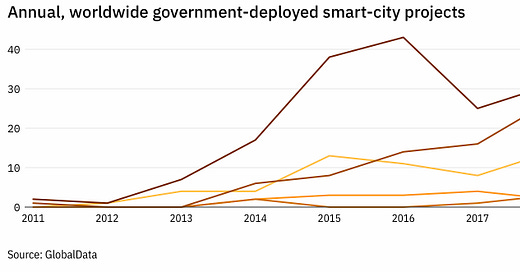

But the most recent evidence suggests that the idea is losing its lustre, according to City Monitor, and that this was happening even before the pandemic:

Concerns around privacy, of who should own or control public data and to what extent technology is always the answer could be heard loud and clear at least a couple of years before Covid-19 changed the world. Backlash against the practices of companies like Amazon and Facebook helped spur the grassroots movement that ultimately contributed to the cancellation in May of a major Sidewalk Labs project in Toronto.

But there’s a deeper shift going on—and one is that is driven by more positive trends about how urban success is measured:

These questions were all present prior to 2020. In 2021, the idea that the goal of every city should be to get smarter feels painfully out of touch…. as with so many other aspects of life on our planet over the past year, it is starting to feel like the end of an era.

“Part of it is that people are sick of talking about this term, ‘smart cities’,” says Story Bellows, a partner at the urban-change management consultancy Cityfi. “People are more focused now on creating outcomes in their communities, whether that’s using technology, whether that’s reinventing processes – kind of the layering of all of those various approaches to making meaningful change on key indicators, whether it’s on health or equity or whatever it is.”

This reminded me of a workshop I attended a few years ago at Lancaster’s Institute of Social Futures, convened by the late John Urry, called Smart Cities vs Happy Cities. There’s not a record of the event online, but I summarised John’s notes on some of the features of the “happy city.”

“Happy cities thus involve a smaller scale system of neighbourhoods, indeed with cities fragmented into more self-sufficient neighbourhoods without rigid zoning.”

“Collective ownership would also be key. Car-[and bike-] sharing schemes are an example of a new ‘access’ economy incorporating wider systems of mobility.”

“A liveable city would involve much less energy use through enabling social practices on a smaller scale.”

“Happy cities involve re-designing places to foster higher density living and shifting towards practices that are just much smaller in scale….There should be a systemic reduction in distances travelled by people, objects, goods and money.”

Finally, and this is an important point: “Such a city would be one with reasonable levels of wellbeing although in terms of normal economic measures most people would be ‘poorer’.”

Of course, this still involves technologies. But to different ends, and probably controlled by different people.

#2: The post-pandemic recovery

It’s a year since I went into lockdown (the British government caught up about a week later), and we are probably about halfway through the immediate health crisis. Vaccines are being rolled out, we understand the virus better, we are quicker to spot new variations.

But the economic crisis is still at an early stage, so it’s worth noting what the Managing Director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, had to say about it. Especially given that in the aftermath of the last crisis it was a hawkish advocate of austerity and debt reduction.

It seems that the world his moved on since then. Georgieva is concerned both about what she calls ‘the great divergence’, both between countries, and within them.

Between:

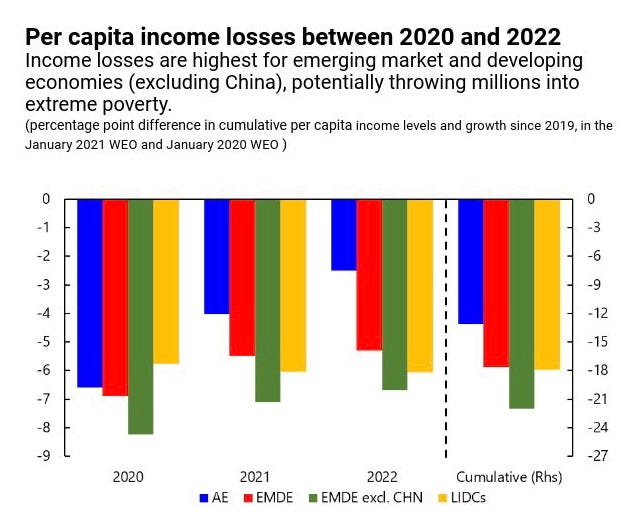

We estimate that, by the end of 2022, cumulative per capita income will be 13 percent below pre-crisis projections in advanced economies—compared with 18 percent for low-income countries and 22 percent for emerging and developing countries excluding China. This projected hit to per capita income will increase by millions the number of extremely poor people in the developing world.

(Source: IMF. The blue bar is for ‘advanced economies’)

Within:

the young, the low-skilled, women, and informal workers have been disproportionately affected by job losses. And millions of children are still facing disruptions to education. Allowing them to become a lost generation would be an unforgiveable mistake.

Georgieva sees three priorities:

Step up attempts to end the health crisis, including rolling out the vaccine more quickly to developing countries: “Faster progress in ending the health crisis could raise global income cumulatively by $9 trillion over 2020–25.”

Step up the fight against the economic crisis. So far governments have spent nearly $14 trillion to mitigate the economic crisis, and they need to continue to do this: “The key is to help maintain livelihoods, while seeking to ensure that otherwise viable companies do not go under.”

Step up support to vulnerable countries, who could face an impossible choice “between maintaining macroeconomic stability, tackling the health crisis, and meeting peoples’ basic needs.” The IMF may step up itself here by issuing a new Special Drawing Right to boost government reserves without increasing debt.

And a reminder: the report I wrote for SOIF on ‘The Long Pandemic’ can be found here pdf)

j2t#056

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.