19th May 2023: Cities | Photography

In praise of street experiments. // Re-imagining William Blake

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: In praise of street experiments

I haven’t written here much recently about cities, transport or urbanism, but I enjoyed a long thread on Twitter on this subject recently by the University of Toronto academic Jedwin Mok. I’ve turned it into a link on Thread Reader: you have to dodge the adverts but it is more or less readable. (But I do wish that people who write long Twitter threads would also just turn them into posts somewhere as well).

The piece falls into two halves. The first is about the myths that North Americans tell themselves to explain why European cities are so much more liveable than their own. The second is about tactics to change the urban agenda away from cars. I’ll follow his narrative here. But if you want to skip ahead: the tactic is “street experiments”.

The two big myths are: #1, “European cities are old”; and related, #2, ”European cities were built before the car”. In fact, Europe’s more liveable cities came about through public protest and participation.

On myth #1, Mok points out that many of Europe’s cities were more or less flattened during World War II, notably in Germany and the Netherlands. Some were rebuilt on their old street grids, some (like Rotterdam) were so badly damaged that they were rebuilt anew.

On myth #2, European planners caught the car bug as much as American ones (or British ones) did, forcing cars into the cities and drawing up plans to drive motorways into the city centre. (I wrote about some of that British experience here).

In Europe,

Swaths of urban space were repurposed for moving and storing cars, causing decay and disinvestment in inner cities. These plans received scrutiny and opposition... To solve the congestion of 1960s Amsterdam, planners introduced a massive highway plan, “Plan Jokinen,” set to demolish historic neighborhoods.

In some cases, they faced quite serious opposition. The Amsterdam campaign against Plan Jokinen was called ‘Stop de Kindermoord’, which translated into ‘Stop child murder’.

This was

a massive protest movement against traffic violence (and heavily influenced NL “sustainable safety” traffic policies). Similar demonstrations were held in other cities as a reaction.

What’s interesting is that in the face of this divided opinion cities started turning to direct votes on traffic plans. Groningen, for example had a vote on whether to ban cars from a road through a city centre park.

(Photo by Frank Straatemeier, courtesy of Gemeente Gronigen)

The vote against cars was won by 51% to 49%. This small margin was the start of Groningen’s innovation in sustainable mobility, in which it is now seen as a leader in the Netherlands.

So how do you test what people might like? Mok’s thread is about a trip to Europe last year in which he learned about “street experiments”. He has come back a fan:

I now strongly believe they are the single most effective tool for rapid urban change and public participation.

This is his definition:

Street Experiments are temporary and low-cost changes to the urban realm, usually reallocating space used by private cars for other forms of mobility or activity. Experiment is the key: disruptive changes to urban space can be tested without significant commitment.

In writing about them, he pulls out four principles that make them effective:

“𝐓𝐞𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐫𝐲” 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐭𝐡

Experiments are cheap and quick to implement. What matters isn’t quality, but the reallocation of space for other uses. It’s easy to sell to the public on temporary measures; if it doesn’t work, remove it! Here’s a “schanigarten” (outdoor patio) in Munich. Simple benches and tables have turned subsidized street parking into economically productive dining space.

𝐀 𝐩𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐮𝐥 𝐭𝐨𝐨𝐥 𝐭𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐮𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐜 𝐬𝐩𝐚𝐜𝐞

Unlike abstract renders or public consultations, change is made tangible with an experiment. Planners/residents can physically test & observe effects, visualizing in real time how space is utilized.

Munich again:

(Photos from @jedwinmok)

As he says: “the existing realm of possibility is broken”.

𝐒𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐞𝐭 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐩𝐮𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐨𝐨𝐥𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐯𝐞𝐬

In Munich, we had the opportunity to turn street parking into a parklet. No lengthy ‘community consultation’ required, just a permit from the city. (North American) planners would regard this as ‘authoritarian’ or ‘inconsiderate.’ Surely, there would be backlash from the local community. Instead, the opposite happened: Even during construction, people walking by became curious and engaged. Many asked questions, tried the parklet, and some even offered a helping hand.

But the important change here is that because the change is actually being tested in public space it engages people who use the space rather than those who go to meetings:

Since change is tangible, projects are experienced and critiqued by actual stakeholders - including marginalized groups who are often excluded from traditional public engagement processes.

(Photo from @jedwinmok)

𝐃𝐚𝐭𝐚 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞, 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞

Street experiments are fundamentally an exercise in data collection. The planning process becomes evidence-based and empirical - centered around measurable outcomes.

He gives an example from Amsterdam where planners turned off a set of traffic lights at a junction. People expected gridlock, but that’s not what happened:

Robust data collection and analysis proved that road users became more aware - while traffic was reduced. Not only was this pilot successful - it was proof that the necessity of traffic controls was to be questioned when accompanied by good street design.

This, he says, is why street experiments work: because you can live in them for a while:

This is fundamentally why street experiments are so powerful for creating permanent and lasting change. Despite being ‘temporary’, they are a concrete implementation of urban change to be experienced, rather than just an idea or visualization to be shown.

There’s a bit more here about why North American cities find this hard to do, even after running some fairly successful street experiments of their own during the pandemic which were typically reversed. He puts this down partly to what he calls a “process fetish”— “where planning is not driven by empirical outcomes; rather by the appearance of equitability within the planning process”. And partly to a system where participation requires time and money.

His lesson from his European trip?

building liveable, inclusive, & sustainable cities is a creative exercise requiring constant revision - places that aren't scared of failure, embrace change, and empower people to imagine the impossible.

2: Re-imagining William Blake

I went last week to visit Photo London at Somerset House—a vast annual photography fair at which scores of galleries and dealers come to show off their stock for four days.

Amongst some classic work (Robert Frank, Terry O’Neill, Bill Brandt, Lee Miller, for example) there was a lot of contemporary photography. Among the contemporary work there were quite a few images about race and ethnicity, and my eye was caught by some work by the British photographer Leah Gordon, who is now based in Haiti.

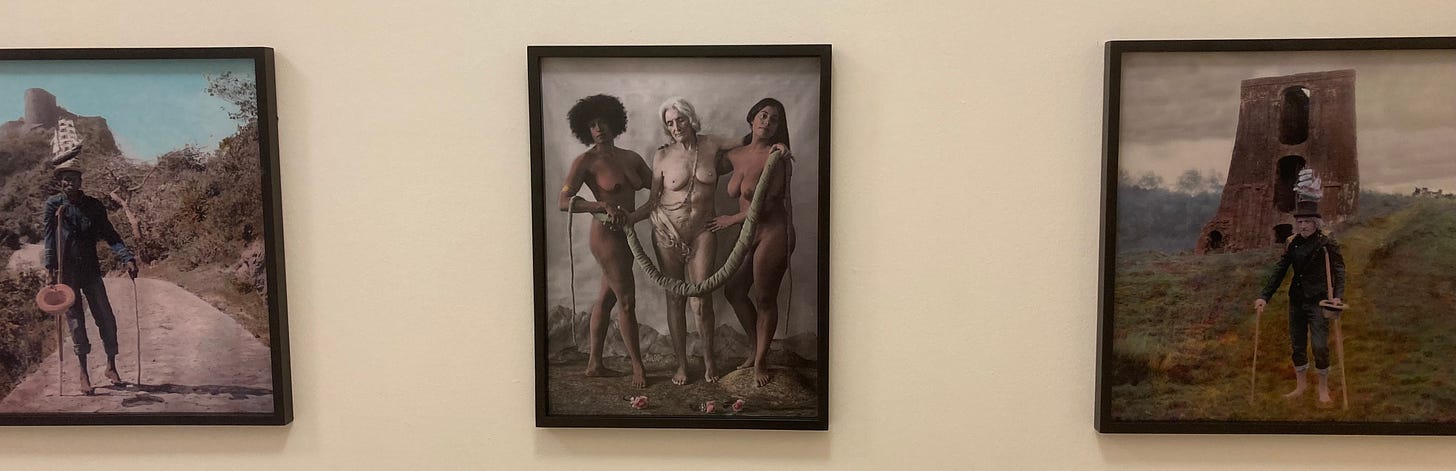

(Leah Gordon, 2019, ‘The Kingdom of the World’. Photo Andrew Curry.)

This isn’t a particularly good photo of her triptych The Kingdom of the World, made in 2019 to mark the 70th anniversary of Alejo Carpentier’s book of the same name. It conveys the idea: you can also look at her work online at the Ed Cross Gallery website.

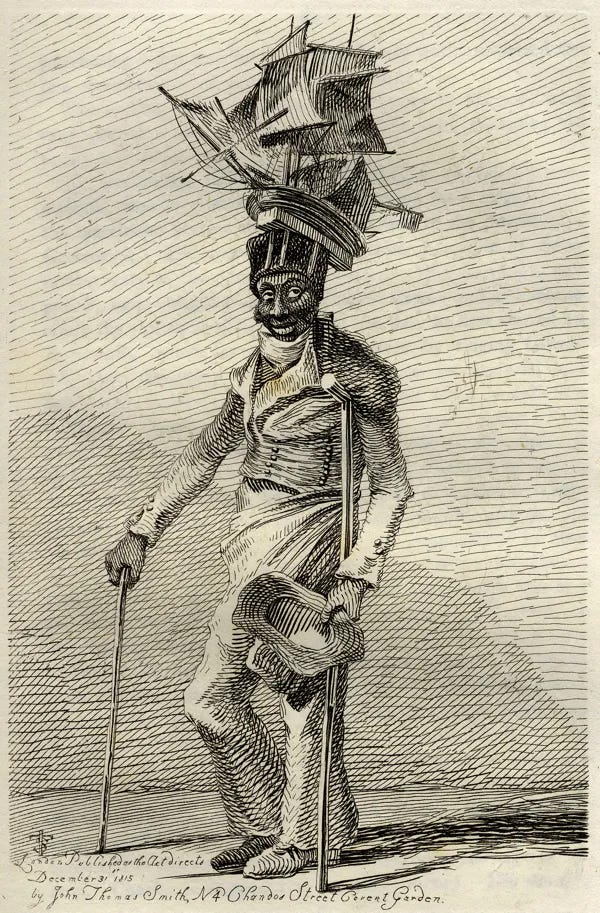

People might recognise the middle image, at least: it’s a reconstruction of William Blake's 1796 engraving of 'Europe Supported by Africa and the Americas’, which is taken from a book used by British abolitionists. It’s another reminder—as if we needed one—of how radical Blake was. Here’s a version of his original.

(William Blake, 1796, ‘Europe Supported by Africa and the Americas’. Public domain.)

The images at either side are re-imaginings of engravings by Blake’s friend and contemporary John Thomas Smith.1 He was a successful engraver, and his book Vagabondia, published in 1817, showed pictures of people who—by Gordon’s account—“chose the life of the vagabond or beggar rather than the misery of working in the Northern factories.” Some of the images from that are online, and there’s a good selection in this article here, including the original of the engraving of the sailor that Gordon has re-imagined in her triptych.

(John Thomas Smith, 1817. From Vagabondia)

The gallery’s note on the triptych says:

Taken as a whole, the triptych portrays the intervolved histories between the disenfranchised British working class and peasantry, the ironic complications of the British abolition movement and the complexities of the Haitian Revolution.

It also says something about the present, which is also “intervolved” with these pictures of a 200-year history. 200 years on, it is finally almost impossible to escape the long shadow of slavery and colonialism, with reparations at last being discussed seriously.

Or come to that, now we are at the other end of modernity, the people who are endlessly cast to its economic edges, in Blaenavon, in Wales, where Gordon’s right hand photograph was made, or Haiti, where the left-hand photograph is located.

Other things: podcasting

During lockdown I recorded a episode of the Facing Up To The Future podcast with Rishad Tobaccowala, of the agency Publicis, which was just used internally as part of Publicis’ internal knowledge programme. Three years on it has been released in to the wild—and apart from some pandemic references it holds up pretty well. According to the blurb, I share

some helpful approaches used by futurists to improve business outcomes, considers how his own work has changed over the past 20 years, and talks about developing futurist capabilities in the next generation of leaders.

It’s 33 minutes, and can be found on Spotify and Apple.

j2t#457

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Smith wrote the first biography of Blake.