Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The price of life

I sat in recently on a talk by Jenny Kleeman, who has just published a book called The Price of Life, which is, at its heart, about the different types of price put on a human life in different forms of cost-benefit analysis. She was clear from the start that she was “not a numbers person”—her approach is more qualitative.

The book is based around 12 different calculations of the price of a human life. In the talk, hosted in person and online by the London organisation and venue Conway Hall, she focussed on just a few of these.

The starting point here is that the cost of saving a life and of taking a life is routinely calculated by a wide range of professionals. They all use dispassionate logic, and they sometimes try to keep their numbers quiet.

But people who think that life is priceless should look away now.

The implicit price of a human life is revealed in everyday decisions that are sometimes mundane. Every time a life-saving measure is described as too expensive to implement, we identify the limits of what a life is worth. And vice-versa. You can think of investment in lifeboats, safety caps on food products, hard shoulders on motorways. Cost-benefit economists have been doing these kinds of calculations since the middle of the 20th century.

In making them, data is used to provide “objective” judgments, and, increasingly, algorithms are applied. But as she observed, this quantification of everyday life has crept into our lives without anyone ever taking a formal decision. It’s one of those phenomena that exists at the level of “good administration” by rational organisations.

But she also concluded after doing her research that there’s no right answer:

I came to this with an arched eyebrow. I came away thinking that sometimes this was useful, and sometimes not.

In her talk she focused on about five of the twelve numbers in her book.

The first cost of a life comes from what you would pay a hitman. The best estimate she had for this was £15,180, which she thought “surprisingly affordable”, but added that we only have data from the hitmen that get caught.1 The good ones might be more expensive. As Kleeman noted, there’s a lot of sociology associated with all of this kind of data.

The price of saving a life in sub-Saharan Africa is around $4,000-$5,000. This number comes from GiveWell, which is the most influential charity evaluator in the world. This is the sort of number that sits behind the model of effective altruism. Kleeman characterised effective altruism with two quotes: ‘Give with your head, not with your heart’; and ‘Where will my money do the greatest good?.’

She travelled to San Francisco to research this further, and found that the effective altruists had a graph plotting the optimum age to save someone’s life: eight years old. She also met the effective altruist philosopher Will McAskill, and discussed Giles Fraser’s thought experiment about the burning building which has a Picasso and a child inside it. The effective altruist

would save the Picasso and not the child.

(Save the Picasso, not the child. ‘La soupe’, Pablo Picasso, 1902-03. Art Gallery of Ontario, via Wikipedia. Public Domain.)

You save the Picasso because the money from selling it saves lots of children. (Kleeman didn’t say this, but it did strike me that you could let it burn, save the child in the building, and use the insurance money to save the other children.)

While in San Francisco she also talked to the effective altruists about the city’s terrible homeless problem. But obviously they would never give money to people on the street because homeless people don’t represent good investments in “good”. I think this quote is probably a paraphrase from her interview with Will McAskill, but my notes aren’t completely clear:

You must blind yourself to the problems of the doorstep.

Kleeman’s comment on this:

For me, doing good has to be more than an accounting problem. Doing good is about building the world we want to live in together.

The third example she discussed was from COVID19 and lockdown. Andrew Cuomo, the then Government of New York, said that the cost of a human live is priceless. Rishi Sunak, then the UK finance minister, said that we would do “whatever it takes”, regardless of the bill.

In fact, the bioethicist Simon Wood told Kleeman that savings lives from COVID cost six times as much as saving lives from any other intervention.

This took us into the world of QALYs—quality adjusted life years. The cost of a QALY was set at £20-30,000 in 1999, when the UK’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence was created, and has stayed the same ever since. It’s not a particularly scientific calculation: it represents the cost of a year of dialysis in 1999. But because it’s a known number it leads to a complex financial dance with pharma companies about the price of new drugs.

Is a death from COVID six times worse than other deaths? Well, probably not. Wood told Kleeman that you’d get a much better return if you spent the money on alleviating poverty. I wondered if this might not be the full calculation, since we also threw money at COVID to make sure that the National Health Service wasn’t overwhelmed, and because we needed to maintain the structure of society in the face of the pandemic. Because, as she said, the cost of saving a life is also about justice and fairness.

The other side of measuring the cost of saving a life is the cost of creating a life. In the UK, one in six couples have fertility issues — and I’m guessing that the figure is similar in other parts of the rich world.

In the UK, most people going through fertility treatment pay for it. The average cost is £13,700, but there is a very long tail. A significant proportion of couples pay more than £30,000, some pay £100,000. For Kleeman, this raised the question of whether only the biologically fortunate or the wealthy should be able to have children.

Looking at life through its price also shows where there is unfairness. Crime is one example. The UK’s Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority tariff for a death of a family member is £11,000, which isn’t enough to change your life. This hasn’t been changed since 2012. You get more for the loss of leg above and below the knee, because have to live with it. The CICA is the body you turn to when there is no-one to sue.

She looked at this through the lens of the London Bridge attack, in which eight people were killed: three French, two Australians, two Canadians, one Briton, one Spanish. Two were killed by a van on London Bridge, the others stabbed in the nearby Borough Market.

So this is an exercise in international comparison, and the scales here suggest that the victims of terrorist attacks are regarded differently in some countries. Spain, for example,

has a special fund for the victims of terrorism, and pays €250,000. Australia pays $A75,000 (about £40K), the UK, as above, £11,000, and Canada C$10,000, which might just about cover getting the body home and buried. France, inevitably, has a complex bereavement scale.

The van had been hired from Hertz by the killers, and the families of the two people killed by it sued Hertz. Their insurers paid out close to £1.5 million per life — around 140 times as much than the British person killed by a knife minutes later.

Kleeman suggested that looking at the price of life in this way shows “what we value”. So we can use it as a tool to try to get closer to justice and fairness, but all it really does is to show us where injustice is. The numbers don’t show the true value of everything. As she remarked:

The prices are only meaningful if we reduce the people to a series of indices, and that is a dangerous thing.

2: The accelerating energy transition

At her Sustainability by Numbers blog, Hannah Ritchie has some quick notes on a big recent deck from the environmental researchers Rocky Mountain Institute [RMI] on the rapidly shifting economics of transition. It’s written by Kingsmill Bond, Sam Butler-Sloss, and Daan Walter.

There’s more than 80 slides here, and so I’m just going to point to some of Hannah Ritchie’s comments and maybe add a couple of my own.

Her headlines first:

Most of the world’s energy is wasted, and there is lots of room for efficiency gains

'Most’ here means that around two-thirds of the primary energy from fossil fuels doesn’t get used productively—it vanishes into thermodynamic and system losses. So electrification can produce a lot of system efficiences.

Electrification drives efficiency

Electric vehicles need 3 to 4 times less energy than petrol ones. Electric heat pumps are around 3 times as efficient as a gas boiler.

This is true pretty much everywhere when you electrify, which RMI has a good chart on.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

China is electrifying quickly

This is the other part of the story I told earlier this week about China’s EV industry. Over two decades, China’s share of final energy use provided by electricity has gone from nowhere to overtake all the other leading economies. I think this is down to national strategy—RMI suggests it’s because the cost of natural gas in China is higher than electricity, whereas it is cheaper in the USA and Europe. Of course, both of these things can be true at the same time.

Time to electrify transport

Transport is way behind other sectors in electrifying—most vehicles are still powered by fossil fuels. Almost all the electrification has taken place in buildings and industry, while—over a century!—transport has barely shifted. It represents a big win in moving away from fossil fuel use.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

The energy transition narrative is shifting

The RMI deck has some slides on the way this narrative is shifting, and I thought these were the most interesting part of the deck, partly because I have a belief that rapid change has to follow narrative change.

This is how Hannah Ritchie summarised this part:

In 2015, renewables were expensive. Not anymore.

Headlines claimed that 10% to 20% of solar and wind on the grid would break it. Many countries have easily passed these thresholds, and their grids are still standing.

Electric vehicles were a pipe dream. Now, most manufacturers are going electric to dominate the future market.

But in some ways this is the ‘rational’ policy part of this reframing. There are several slides throughout the piece that suggest that this all goes deeper.

The first slide contrasts and ‘old’ versus ‘new’ narrative, in which business as usual fossil fuels are challenged by more dynamic and more beneficial clean technologies.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

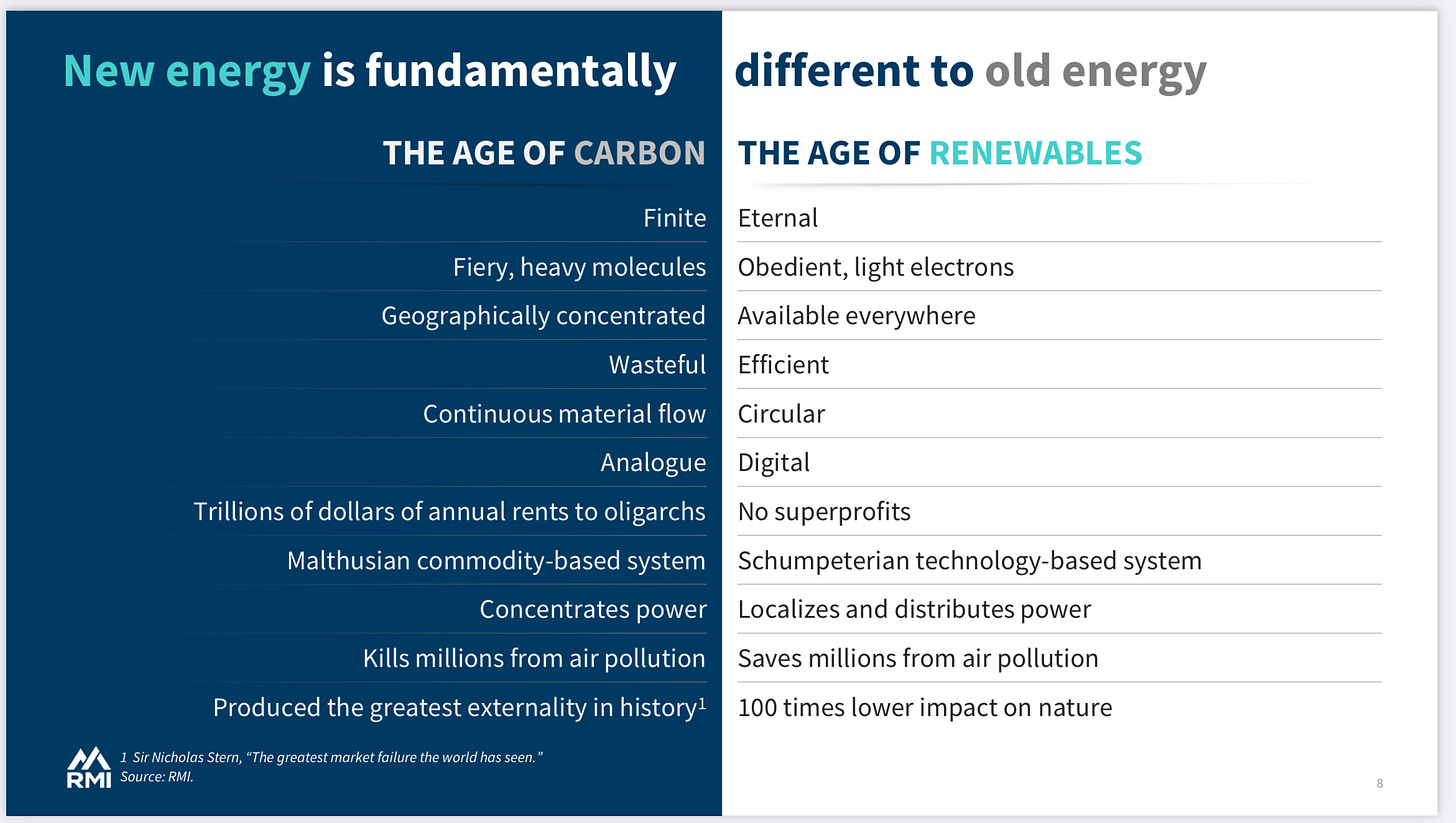

In addition, the two energy technologies have very different qualities, and a chart captures a set of oppositions between them. From a narrative point of view this is a classic way in which narratives get described: finite (fossil) versus eternal (renewables); wasteful versus efficient; material flows versus circular economies; analogue versus digital; molecules versus electrons; Malthusian versus Schumpeterian (!); concentrated versus distributed. And so on.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

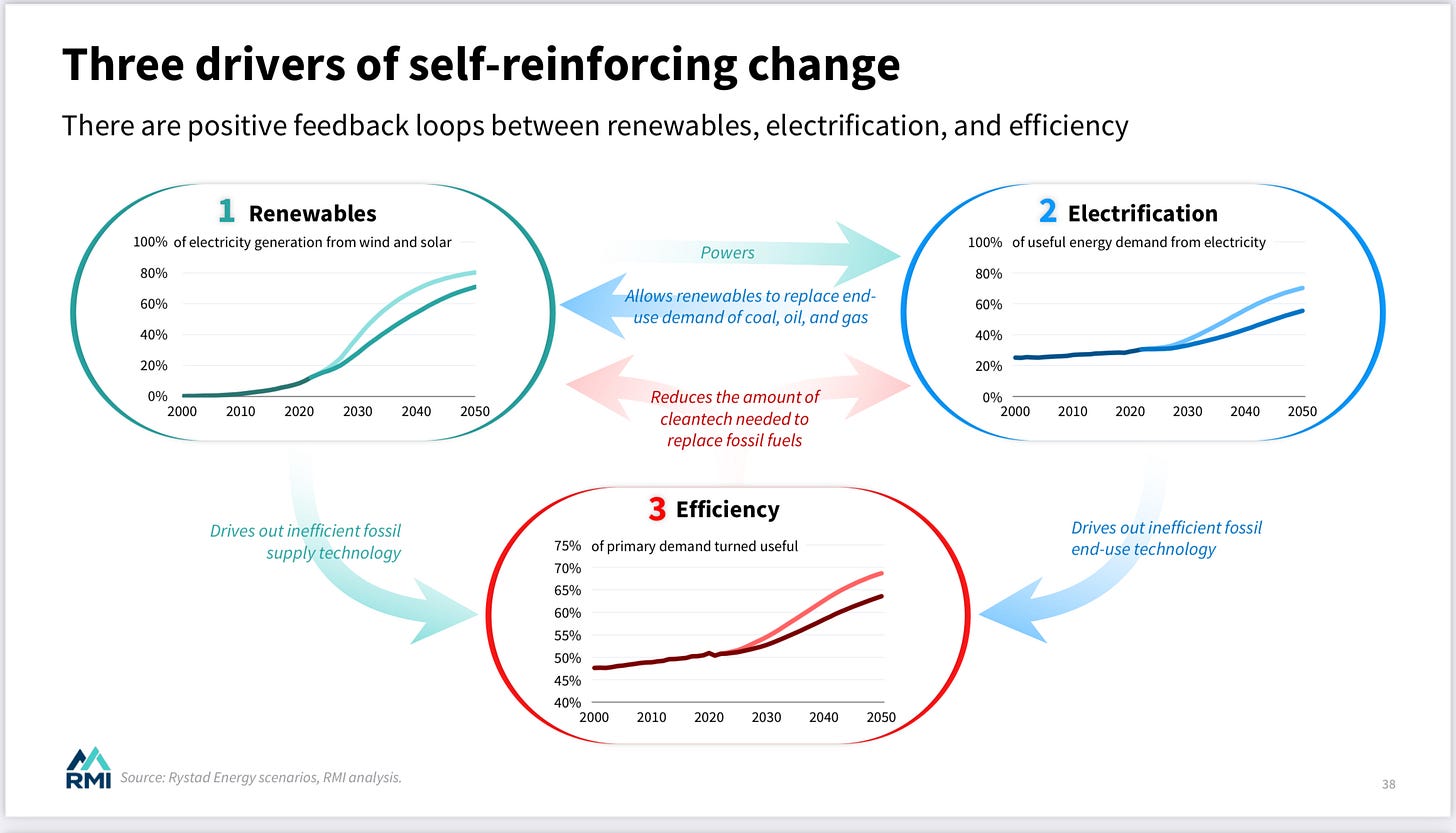

There’s also a powerful systemic push to accelerate transition. They see three elements here: renewables, efficiency and electrification. Renewables increase efficiency and electrification; together renewables and electrification combine to increase efficiency (this isn’t quite a flywheel). And electrification does increase demand for renewables which (they don’t say this) will increase economies of scope and scale.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

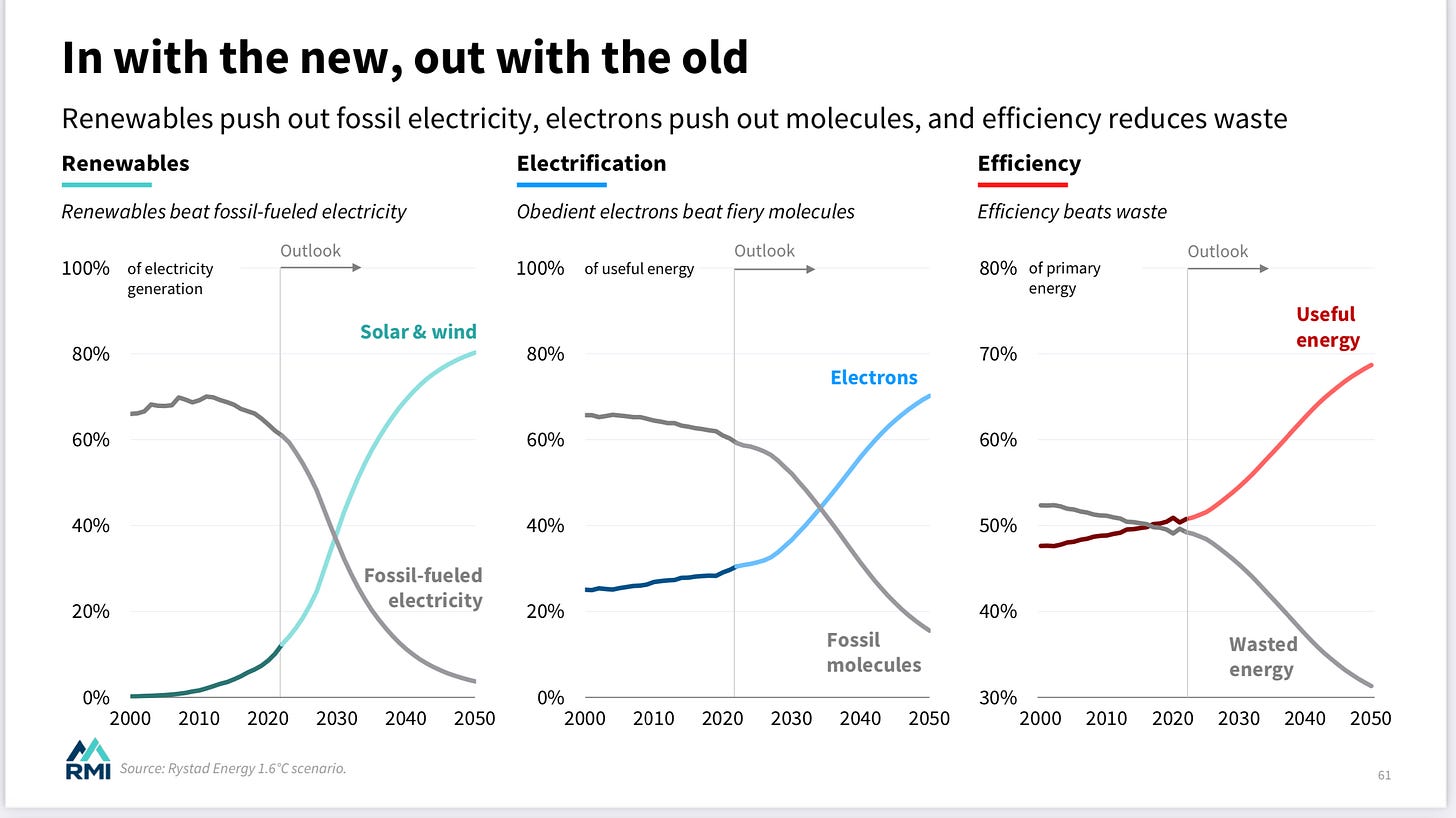

Finally, there’s a set of S-curves here, part historical data, part projection, which show a classic Horizon 1 in decline and Horizon 3 moving up to replace it. Each of these curves measures a dimension on the three elements in the chart above.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

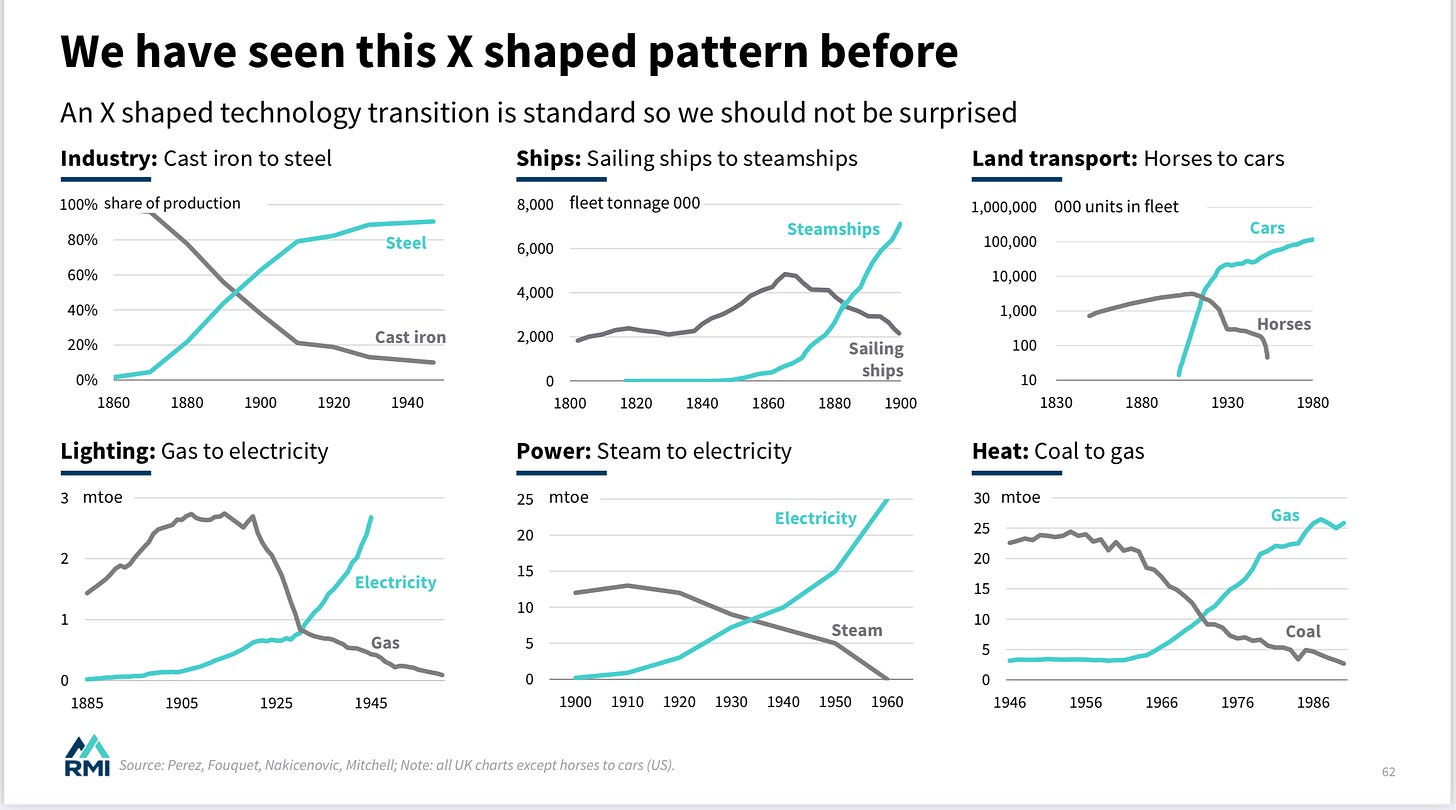

Curves like this are familiar to historians of technology, as they remind us on the next slide. We have been here before.

(Source: Rocky Mountain Institute)

There’s a tonne of data in the deck—I’ve barely scratched the surface here. If you’re interested in the energy transition from a practical perspective, a technology perspective, or a policy perspective, it’s probably an essential read.

j2t#583

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

During the late 1980s I was told by an Irish colleague with some knowledge of the IRA that the cost then of ‘hurting’ someone—Actual Bodily Harm—was around £700-800.