18th March 2024. Privacy | Food

Cars are “computers on wheels” that don’t care about privacy // Transforming the world’s food system is cheaper than you think [#553]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Cars are “computers on wheels” that don’t care about privacy

I’ve come to this a bit late, but the Mozilla Foundation produced a report last year that basically says that cars are the worst category for privacy that it has ever reviewed. The phrase it actually uses: “a privacy hightmare”.

Of course, we don’t think much about cars and privacy, but these days they are basically data-on-wheels:

Car makers have been bragging about their cars being “computers on wheels" for years to promote their advanced features. However, the conversation about what driving a computer means for its occupants' privacy hasn’t really caught up. While we worried that our doorbells and watches that connect to the internet might be spying on us, car brands quietly entered the data business by turning their vehicles into powerful data-gobbling machines.

The Mozilla Foundation reviewed 25 car brands, and all 25 earned their “Privacy not included” label.

There are four reasons why car privacy is so bad.

1. They all collect too much personal data

In summary here:

we handed out 25 “dings” for how those companies collect and use data and personal information. That’s right: every car brand we looked at collects more personal data than necessary and uses that information for a reason other than to operate your vehicle and manage their relationship with you.

Dings aren’t good. You can benchmark this, as they do here, by comparing cars with other categories that aren’t good at privacy, such as mental health apps, where only about three-fifths were dinged by Mozilla for privacy failures.

They say it’s worse than this, because car companies also have lots of opportunities to collect data, compared to other apps:

They can collect personal information from how you interact with your car, the connected services you use in your car, the car’s app (which provides a gateway to information on your phone), and can gather even more information about you from third party sources like Sirius XM or Google Maps. It’s a mess.

In fact there’s so much going on here, that Mozilla wrote a separate article outlining all of the ways that cars companies breach your privacy.

(Mercedes digital dashboard, via Wikipedia. Collecting data and sending it on. Image: Robert Basic, CC BY 2.0))

2. Most of them share or sell your data

84% of the car companies share your data, with service providers, data brokers, and others. 76% say they sell your data. And to add some icing to this particular cake, more than half will hand over your data to government agencies if requested, even if this is just an “informal request”.

car companies' willingness to share your data is beyond creepy. It has the potential to cause real harm and inspired our worst cars-and-privacy nightmares.

We know about the uses of personal data because of state laws (such as those in California) that require companies to disclose it. But there’s probably also a whole other business here in using aggregated data that we don’t know anything about.

3. Most give drivers little to no control over their personal data

Only two car brands gave their users permission to delete their personal data. (Renault and Dacia, for the record, both part of the same group). Their cars are only available in Europe, where they therefore need to comply with GDPR, which is probably the reason for this.

4. We couldn’t confirm whether any of them meet our Minimum Security Standards

The ‘Minimum Security Standards’ are Mozilla’s assessment of basic security standards, but the privacy policies published by the car companies don’t have enough information in them to assess this. Again, other sectors where you’d expect less publish more information here:

dating apps and sex toys publish more detailed security information than cars

And they didn’t just try to make sense of the privacy policies. They emailed them as well:

Our main concern is that we can’t tell whether any of the cars encrypt all of the personal information that sits on the car. And that’s the bare minimum! We don’t call them our state-of-the-art security standards, after all. We reached out (as we always do) by email to ask for clarity but most of the car companies completely ignored us.

This might have been because their cybersecurity records are terrible. Just looking back over three years, to 2020, the researchers found that two-thirds of these brands had enough leaks and hacks to put their drivers’ privacy at risk.

Some of the specific information about particular brands is worth sharing as well:

Tesla is the worst offender here (no surprise there, I think) — “only the second product we have ever reviewed to receive all of our privacy ‘dings.’”

Nissan—second to bottom—collected some of the “creepiest data” seen by the researchers, across multiple categories:

“It’s worth reading the review in full, but you should know it includes your ‘sexual activity’... Oh, and six car companies say they can collect your ‘genetic information’”.

In terms of sharing data with enforcement agencies, Hyundai is the worst: “In their privacy policy, it says they will comply with ‘lawful requests, whether formal or informal.’ That’s a serious red flag.”

It turns out that most of these companies have signed up to a list of Consumer Protection Principles developed by the US industry group Alliance for Automotive Innovation. (Renault and Dacia haven’t signed, probably because they don’t sell in the US, and also Tesla, inevitably).

the number of car brands that follow these principles? Zero. It’s interesting if only because it means the car companies do clearly know what they should be doing to respect your privacy even though they absolutely don’t do it.

Of course, there’s also not obvious things that consumers can do here, since all of the companies are data nightmares, people don’t generally shop for cars on privacy—there are dozens of other criteria involved in the purchase decision—and because for many people a car is a necessary purchase. It’s hard to boycott the category in protest.

And they do this work all the time, and spent weeks on the research, and even they were confused by the claims made, and not made, by the car companies.

There’s also no real consent here. Tesla says that you can opt out of data collection, for example, but the rest of this section also says that if you do so your car might stop working:

If you choose to opt out of vehicle data collection... (t)his may result in your vehicle suffering from reduced functionality, serious damage, or inoperability."

So this is another case where it shouldn’t be down to consumers to try to make informed decisions about they need to do. There’s no informed choice to be made here. This is down to lawmakers and regulators—but as the Mozilla Foundation says, you can take the first step in that direction by supporting its ‘Privacy for All’ campaign.

2: Transforming the world’s food system is cheaper than you think

The Food System Economics Commission (FSEC) is an independent economic commission funded by a group of foundations.1 It has just published a substantial report on funding the food system transformation. I’m going to summarise the main points from the executive summary here, having had time only to skim through the rest of it.

Their starting point: on the one hand, food systems

have achieved something of a miracle, keeping pace with decades of population growth while decreasing some forms of malnutrition, reducing poverty and increasing life expectancy.

On the other, the recent evolution of food systems has inflamed many pressing global issues, including “persistent hunger, undernutrition, the obesity epidemic, loss of biodiversity, environmental damage and climate change”. They put a price on the damage that food systems are currently doing:

The economic value of this human suffering and planetary harm is well above 10 trillion USD a year, more than food systems contribute to global GDP. In short, our food systems are destroying more value than they create.2

Prices here—throughout this piece—are at US$2020 purchasing power parity. Despite these external costs, the authors observe that food systems haven’t really had the scrutiny they deserve. Yet transforming food systems can make a big contribution to biodiversity, to climate change, and health:

such a transformation is not only biophysically and technically feasible... The net benefits of achieving a food system transformation are worth 5 to 10 trillion USD a year, equivalent to between 4 and 8 percent of global GDP in 2020.

Since people sometimes are a bit blind to the costs of the current food system, it’s worth briefly spelling out where they happen:

Health costs, which FSEC estimates to be at least 11 trillion USD. The economic costs of ill health due to food systems are measured through their negative effects on labor productivity. Those are driven by the prevalence of non-communicable diseases.

Environmental costs are estimated at 3 trillion USD a year and reflect the negative impacts of today’s food systems on ecosystems and climate... These practices are responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Finally, food systems are a source of structural poverty through the costs of food, but also through the low incomes of many who work in food production.

That’s where we are today. They have also modelled outcomes to 2050 based on a “Current Trends pathway”, and this shows increases in the number of obese people, vulnerability of food systems to climate and environmental degradation, continuing deforestation, and increasing nitrogen surplus and related pollution.

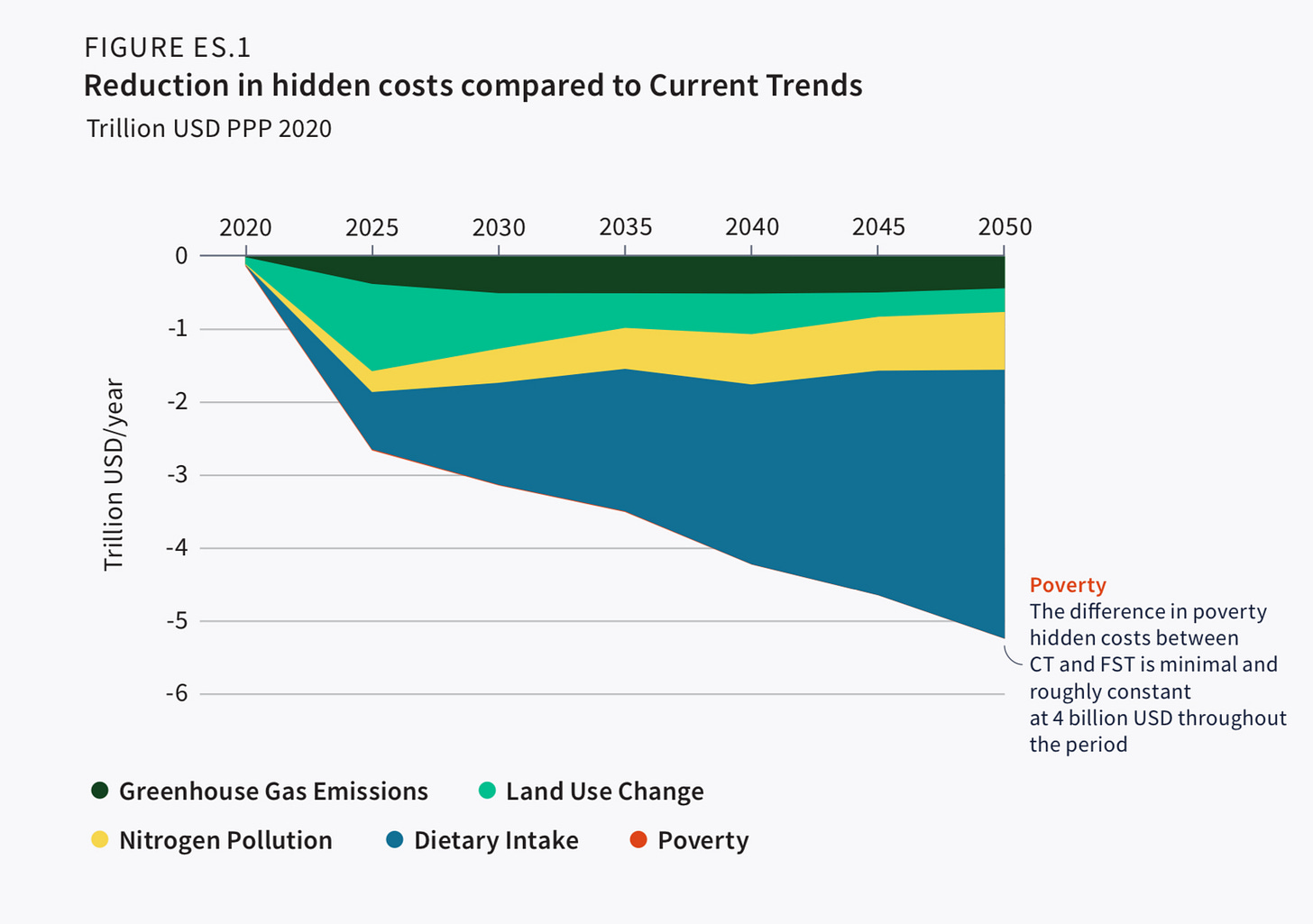

The FSEC has also modelled what it calls a “science-based transformation pathway for the food system”, called the FST or Food Systems Transformation—the “good future” rather than the “bad future”, I guess, although they don’t call them this.

This pathway is built around five goals—on diet, livelihood, biosphere, climate, and resilience—which I’m just going to list here. There is some “how” in the report:

Consumption of healthy diets by all

Strong livelihoods throughout the whole food system

Protection of intact land and restoration of degraded land

Environmentally sustainable production throughout the food system

Resilient food systems that maintain food and nutrition security in the short and long run.

This has better outcomes all round. But one of the salient points here is that the costs of the FST model are small compared to the savings involved.

(Food Systems Economic Commission, ‘The Economics of the Food System Transformation’, p. 10)

They estimate the costs at between $200-$500 million a year worldwide:

about 200 billion USD covers investments in rural infrastructure... the protection and restoration of forests, the reduction of food loss and waste, support for the dietary shift and agricultural research and development.

The other $300 billion is earmarked for transfers and subsidies to ensure that food prices remain affordable for poorer consumers, since they expect agricultural commodity prices to rise. This isn’t the whole story, since incomes will also increase and the pattern of foods produced and consumed will also change:

(A)t a global level, the costs of the food system transformation are equivalent to only 0.2–0.4 percent of global GDP, and clearly affordable compared to the global benefits.

Of course, it’s easier to describe the problem than change it, but there may come a point where the costs of the current food system start to get noticed by Treasury Departments. The report does come with some recommendations on how to get to the FST model.

Moving towards healthy diets is the biggest source of benefits here. Obviously, changing what people eat isn’t easy, but they discuss policies that have had some success, such as restricting the marketing of unhealthy food to children, using public food procurement, taking sugared and unhealthy foods, and reformulating packaged and processed foods.

Resetting incentives (1): Repurposing government support for agriculture. Currently much agricultural support benefits large producers and has harmful environmental, climate, and health effects. (I heard at the weekend that in the UK we pay £65 per hectare per year as a subsidy to grouse moor owners despite the harm they do environmentally). This discussion might sound a bit like deciding to subsidise renewables rather than continuing to subsidise fossil fuel producers.

Resetting incentives (2): Targeting revenue from new taxes to support the food system transformation. For example, transforming food systems into net carbon sinks and reducing nitrogen pollution are two important sources of benefits. This can be paid for by taxing carbon and nitrogen pollution, as recommended by the IPCC and the OECD.

Innovating to increase productivity and livelihood opportunities, especially for poorer workers in food systems. New food system technologies are being developed, mostly by the private sector, but public institutions can help to speed up the development and diffusion of innovations that meet the needs of poorer producers. Some of this might include “lightweight” digital technologies such as in-field sensors etc.

Scaling-up safety nets to keep food affordable for the poorest. This is critical to making food systems transitions politically feasible, since the politics of food shortages and price changes can quickly lead to social unrest. They say:

Experience with cash transfers during the COVID pandemic has redefined what is possible, in terms of making efficient digital payments and targeting vulnerable populations.

There’s a quick litany of things that might get in the way, including fear of political unrest, pushback from vested interests, and siloed policy making by governments.

On the upside, though, they point to signs of change. These include a mix of new political and citizen activism, to new (actual, not silver bullet) technologies, and also the COP28 UAE declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action, which has been signed by 150 countries. There are also examples throughout the report of ‘spotlights on change’, which are well worth a quick scan, on things like the prospects for urban agriculture and increasing women’s access to land.

The report is the outcome of four years’ work, and their background research is published here.

Other writing: Music

At the modest folk music site I write for, the editor and I put together an ‘imaginary CD’ for St Patrick’s Day yesterday—seven tracks each of the best of Irish folk music. You can read them all here—and disagree with them, if you like. But if not, here’s one of the tracks that we picked out to cheer up your Monday. Sharon Shannon and Mundy play ‘Galway Girl’ live in Galway’s main shopping street:

There’s also a link to a Spotify playlist in the article if you just want some Irish background music today.

j2t#553

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The Wellcome Trust, IKEA Foundation, Quadrature Climate Foundation, Norwegian Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI), and The Rockefeller Foundation.

Incidentally, that figure looks which looks similar to the price tag that the FAO recently came up with when they assessed the costs of agri-food systems.