18 January 2025. Energy | Davos

The energy ‘transition’ story is wrong—and misleading // I’m so through with the Davos Risks Report [#627]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The energy ‘transition‘ story is wrong—and misleading

The notion of the energy ‘transition’—from fossil fuels to clean low-or-no carbon energy sources—is right at the heart of the narrative of the switch to a net zero world.

An article by Adam Tooze in the London Review of Books (which may be paywalled) gives a critical reading of the idea of ‘transition’, in the shape of a review of Jean-Baptiste Ferroz’s book More and More and More: An All-consuming History of Energy. It was published by Penguin Books in the UK in October:

The first [transition] was from organic energy - muscle, wind and water power - to coal. The second was from coal to hydrocarbons (oil and gas). The third transition will be the replacement of fossil fuels by forms of renewable energy. The transition narrative is reassuring because it suggests that we have done something like this before.

We owe our current prosperity to these two previous transitions, which have by now transformed living standards in most parts of the world. So in some ways, our story about the green transition is also a reassuring story about our future prosperity. And since energy transitions have—in the past—taken around 50 years, this story even reassures us that we might, despite everything, be just about on track for 2050.

But, as Tooze says, this might not be a reliable model of how energy transition has happened in the past. It might just be a reassuring story, “a fairy tale dressed up in a business suit”. And this is, more or less, the argument that Ferroz makes in More and More and More:

When we look more closely at the historical record, it shows not a neat sequence of energy transitions, but the accumulation of ever more and different types of energy. Economic growth has been based not on progressive shifts from one source of energy to the next, but on their interdependent agglomeration. Using more coal involved using more wood, using more oil consumed more coal, and so on.

In other words, the shift to decarbonise our energy system isn’t just a repeat of something that we have done before, but a fundamentally different kind of energy transition.

Fressoz is a French historian of science. He argues that

historical experience has little or nothing to teach us about the challenge ahead. Any hope of stabilisation depends on doing the unprecedented at unprecedented speed. If we are to grasp the scale of what lies ahead, the first thing we have to do is to free ourselves from the ideology of the history of energy transition.

In arguing that the history of energy is not a story of transition but accumulation, in which each new source increases demand for the others, Fressoz is partly following in the footsteps of On Barak. Tooze suggests that Fressoz

puts paid to the energy transition paradigm by showing incontestably that the great displacement never happened.

This part of the argument is laid out quite extensively by Tooze in the article, but a couple of headlines stand out. The first is that today we use more wood than we ever have before, including for firewood. And the history of our various industrial revolutions involves a lot of wood—even now wooden pit props are used in coal mines.

The second is that we are, similarly, using more coal than ever before:

Oil and coal weren’t substitutes but complements... And when you end coal consumption for power generation, as the UK managed to do in 2024, what do you turn to instead? The giant Drax plant in North Yorkshire now burns wood pellets imported from North America.

(Drax: from coal to biomass. Photo: Chris Allen, via Geograph. CC BY-SA 2.0).

Tooze suggests that we are blind to this because people preferred elegant stories in which a dominant energy technology became a synedoche for a particular historical period: the “age of steam”, the :age of oil”, even the “nuclear age”. Humans love narratives, even when they’re not true. Tooze has a phrase for this: “mono-materialism”.

In this telling there’s a sideswipe at Timothy Mitchell, whose well-regarded book Carbon Democracy argues that the displacement of coal by oil also undermined trade union power. But:

The 1940s and 1950s did not see the displacement of coal by oil, but an acute shortage of energy. Oil was a complement, not a substitute.

In fact, the history of materialism, and therefore of modernism, is just much more messy than this. As Bruno Latour argues in We Have Never Been Modern,

there has been a systematic blindness to the giant entangling of natural resources and technologies that has enabled the expansion and acceleration of modernity.

Fressoz acknowledges a debt to the British historian David Edgerton, who proposes in his book The Shock of the Old—one of my favourite economic history books—that the reason we miss these actual material conditions of modernity is because we are over-interested in innovation and under-interested in the way that systems of production work in practice.

We seem to have the nuclear industry to thank for the dominant ‘transition’ model. It promoted it as a strategy to displace the oil sector. In the 1970s and 1980s, when climate projections started to become alarming, politicians grasped at the idea of transition because it was a way of pretending that despite the challenge of climate change, nothing would need to change. Indeed, the economist William Nordhaus

insisted that economic growth should not be fettered by unduly heavy carbon pricing for fear that slower growth would retard the technological transition.1

You might think that with the benefit of hindsight that he got this the wrong way round, but this idea has a long shadow. I happened to be looking through the 2023 UK Government Office for Science Net Zero scenarios, which are a solid enough piece of work, to see among their ‘key findings’ that:

Economic growth and technological innovation are correlated. There is a risk that a low growth, low innovation world would have fewer technological options for meeting net zero.

Ferroz argues that the model of “energy transitions” is one of the reasons—one of the main reasons—that effective action on climate change has been delayed. In Tooze’s account:

He is no fan of Green New Deals or big-push investment programmes. He has nothing but scorn for the ‘nebulous group of neo-Keynesian experts, NGOs and foundations thriving in the shadow of the COPs’ who ‘regularly put forward estimates of the “cost of transition”’... without any indication of the way this money would ‘change the chemistry of cement, steel or nitrogen oxides, or how it would convince producing countries to close their oil and gas wells’.

He isn’t, however, a climate fatalist. Change is possible. But it involves a break with our economic history, so it’s not comfortable:

It must mark a fundamental break with an otherwise irresistible logic of accumulation. [My emphasis] It doesn’t require unanimity or consensus. It doesn’t require that no one is left behind. What it does require is a powerful coalition to impose its will, to make history in the most radical sense.

Ferroz’s book ends in the early 1990s, and Tooze suggests that since then there has been a surprisingly large decarbonisation of parts of the energy system, notably in the closure of coal-fired power stations. It still involves quite a lot of material, especially of key minerals. Nonetheless it is a change in kind.

Because the book finishes in the 1990s, it misses the global switch in industrial production to East Asia:

Japan and South Korea became the great new centres of steel production and shipbuilding... In the production of steel and cement China recapitulated the entire industrial history of humanity in the space of two decades.

As a result, Europe and the US now account for around 21% of global emissions—although this is understated, of course, because of the displaced emissions associated with their imports from Asia.2

Which means, in turn, that as we work out how to reduce our material impact, that’s a conversation that includes all of the world. Which is why the last few COP meetings have been so scratchy.

This post is already too long, but a couple of notes from me. The first is that a lot of this reminded me of Vaclav Smil’s steady focus on the material nature of production, and therefore both of emissions, and on the materials needed to produce of clean or green energy. He came back to this in an article last year that has as much detail in it as most people will need.

The second is that this is also a reminder of the nature of modernity. Hardin Tibbs and I discussed this in a 2010 paper called ‘What Kind of Crisis Is It?’, which referenced the sociologist Martin Albrow. The dominant feature of modernity, according to Albrow, is that it is always expanding.

That’s why this time is different. Either we engineer a radical decoupling between energy and materials, and the production and consumption of goods or services—and we’ve not done this well so far, partly because of a Jevons effect3—or we are going to have to get by on less.

H/t to Peter Curry for the link.

2: I’m so through with the Davos Risks Report

Every year, about this time, I feel the need to have a look at the World Economic Forum [WEF]’s annual Risk Report, out of a sense of professional duty, and every year I hate myself a little bit more for doing this. FN Longer-term readers will probably know by now that I am not a fan of the World Economic Forum’s annual. X

Because every year, it says nothing and it tells you nothing.

I know: by now I shouldn’t be surprised. The sample

brought together the collective intelligence of over 900 global leaders across academia, business, government, international organizations and civil society.

The analysis

also leverages insights from some 100 thematic experts, including the risk specialists who form the Global Risks Report Advisory Board, the Global Future Council on Complex Risks, and the Chief Risk Officers Community.

In other words, much of the sample is drawn from a privileged group whose deformation professionel and general outlook skews them to be more inward looking and short-termist.

And every year the research team at WEF wrestles with the wholly unsurprising data that this sample produces to try to give it some semblance of meaning. It’s like putting lipstick on a pig. (Which, come to think of it, isn’t a bad simile for the relationship between WEF and the gilded class of people in charge of late-stage capitalism.)

They take their pig-wrestling seriously. The Global Risks Report is produced by WEF’s grandly-titled Global Risks Initiative. They’ve learned something, at least, about the performative nature of late capitalism.

Anyway, for the record, from their Global Risks Perception Survey (their caps), here’s their chart of short-term (two year) and longer-term (ten year) risks as assessed by the WEF sample.

(Source: WEF Risk Report, 2025)

And a quick scan tells you that the short-run risks are the kind of thing you’d get from asking people to tell you what news items they remember from the news coverage they have seen in the last year.

In 2021, ‘infectious diseases’ made the top five. In 2016, ‘involuntary migration’ came top of the short-term list. There’s no obvious signs of any reflection going on here.

As they try to make the data more meaningful, the Global Risks Initiative team does a cross tab of the two year and ten year risks, which produces this chart:

(Source: WEF Risk Report, 2025)

It looks nice, but it still shows you that even this group—which includes a lot of people who have contributed to worsening climate change—thinks that climate change in its various forms is the most severe threat facing us.

As Ian Christie noted in an email he sends out,

as ever, the report is written in the strategic passive voice, with no analysis of where the multiple alarming risks come from or who has failed to get a grip on them - or who benefits from making them worse. From the report:

“This long-term outlook has remained similar to the survey results last year, in terms of its level of negativity, reflecting respondent skepticism that current societal mechanisms and governing institutions are capable of navigating and mending the fragility generated by the risks we face today.”

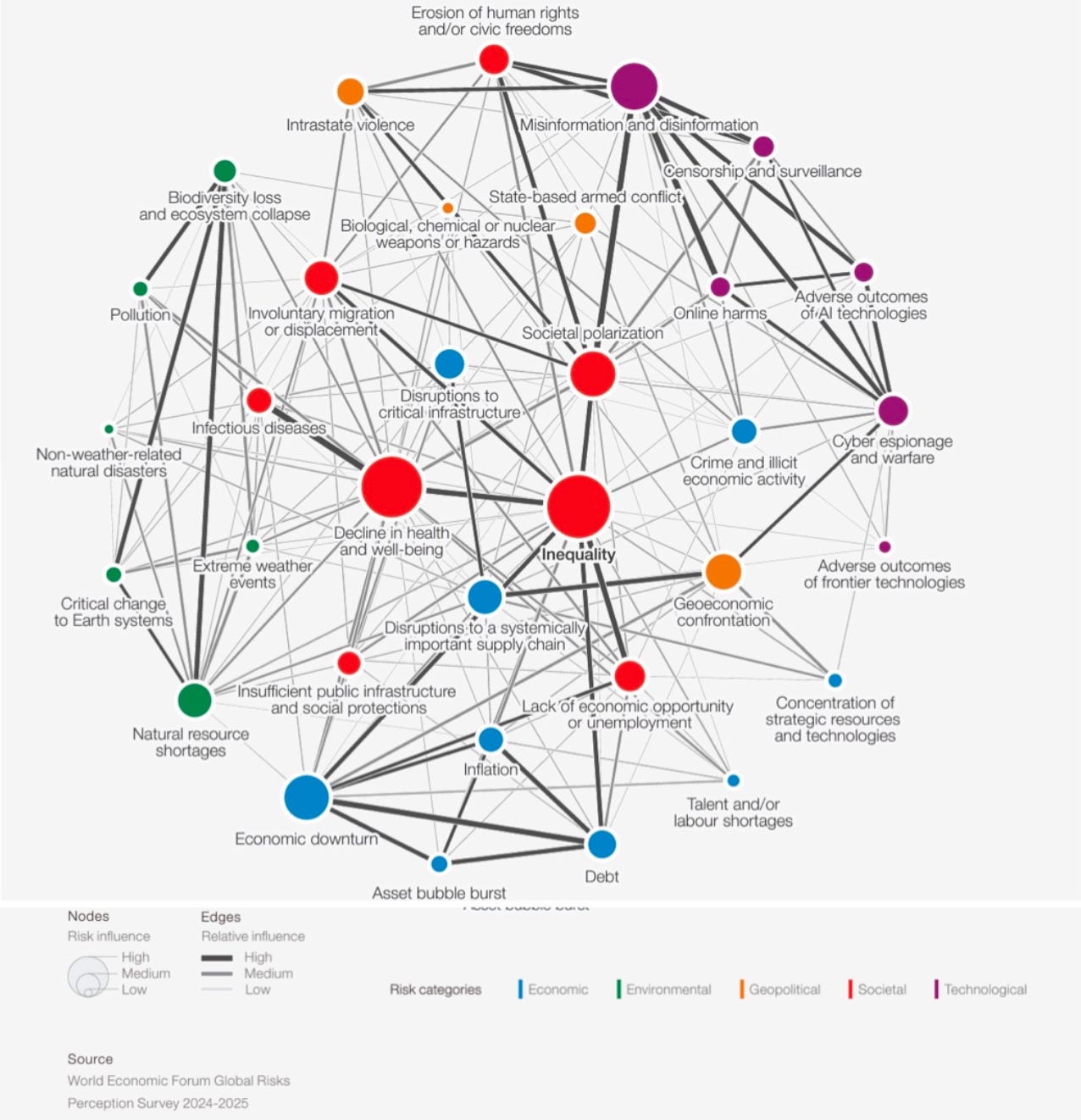

And this becomes even clearer when you look at the inter-connections map (methodology not clear, but seems more likely to have been generated by the ‘thematic experts’.

(Source: WEF Risk Report, 2025)

Some of this is useful, at least, even if, somehow, the analysis manages to take the climate and biodiversity risks rated as the most significant over a ten year period (as per the previous two figures) and relegate them to the fringes of the diagram. If I’d been shown this by a project team, I would have sent it back to give the team an opportunity to think it a bit harder about the impacts of the drivers.

All the same: Misinformation connects to the erosion of civil rights, censorship and surveillance, and societal polarization.

Inequality is connected to both societal polarization and to decline in health and well-being, in what looks like a negative reinforcing loop.

But we know that Facebook will be at Davos, just after they have taken steps that will almost certainly increase the level of misinformation in the world’s information systems, no doubt with Elon Musk, currently the world most active source of misinformation and disinformation.

And so will the senior executives of all the food companies whose product and marketing policies are actively contributing to the decline in health and wellbeing (see the Update on Ultra-Processed Foods below).

And most egregious of all, so will all the American banks and investment houses who have just used the election of Trump to back out of the Net Zero Banking Alliance. Climate change risks be damned when there’s money to be made.

Because when it comes to lipstick, the World Economic Forum has never seen a pig it doesn’t like.

Update: Ultra processed foods

For those following this issue, Marion Nestle published some links to a set of resources on it at her Food Politics blog this week. They are a set of factsheets on UPFs published by the US Right to Know, and although there doesn’t seem to be an easy way to link to all the factsheets in one link—Nestle has laid them out individually in her post—I also see that doing a search for ‘ultra processed foods’ at the US Right to Know produces an informative set of articles.

j2t#627

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Nordhaus’s calculations of growth and technological transition had climate change stabilising at between 2.7 and 3.5 degrees.

Their current share of global emissions is 21%; current share of global population is 13%.

The most recent example of the Jevons effect in operation is that the energy demand from datacentres means that electricity companies in some places are having to delay plans to shutter their coal plants to meet this demand, as The Register reported in October.

Adam Tooze isn't quite right to assert that the book only takes us up to the 1990s. The last few chapters do deal with recent events, including for example the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in the US.

Perhaps Fressoz can be criticised for excess pessimism over the continuation of fossil fuel growth in recent years. Yes, solar panels and wind turbines take energy and other resources to make - an example used in the book - but the 'payback' is a matter of months. We are a long way of reducing global emissions but renewable energies can and are replacing fossil fuels at a increasingly rapid rate.

Thanks as ever for these stimulating articles Andrew.

Your discussion of energy reminded me of this piece by Richard York from 2017, “Why Petroleum Did Not Save the Whales” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023117739217. Because we tend to conceptualize systems as input-output models we miss that advances or shifts in one part often feedback into acceleration in others.