17 December 2021. Business | Jazz

Strategy+Business’ best business books of 2021 also tell a story about business. | Louis Armstrong’s flying trip to pre-independence Ghana

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Strategy+Business’ best business books of 2021 also tell a story about business.

I’ve been meaning to write about strategy+business’ list of the best business books of the year, because, over the years, I’ve found that it’s a good way to take the temperature of how people are thinking about business.

And that seems to be the case this year.

S+b has seven categories—leadership, strategy, economics, management, tech and innovation, consumer behaviour, and narratives. (I’ll park the last one, since it tends always just to be a great business story, as it this year: Unstoppable, by Joseph Greene, on Siggi Wilzig, who survived Auschwitz and built a brilliant Wall Street career.)

The other six are:

- Excellence Now, by Tom Peters

- Open Strategy, by Christian Stadler, Julia Hautz, Kurt Matzler, and Stephan Friedrich von den Eichen

- Shutdown, by Adam Tooze

- Beyond Collaboration Overload, by Rob Cross

- Your Computer is on Fire, edited by Thomas S. Mullaney, Benjamin Peters, Mar Hicks, and Kavita Philip

- Four Thousand Weeks, by Oliver Burkeman.

—

(Image: strategy+business)

And before I go on: The fine business books written by women this year maybe didn’t reach strategy+business this year. Just a wild guess.1

Leaving that rather large point to one side, all of these books, in their different ways, reflect the sense that business doesn’t really know what it’s for or how it should work anymore.

The format here is that a well-regarded academic or journalist writes about each category. So for example, Ryan Avent writes about economics (Shutdown), James Surowiecki writes about consumer behaviour (Four Thousand Weeks), and so on.

Tom Peters, now well past the age at which you might describe him as a ‘veteran’, has written a short book that distils the countless books he’s written down the decades. Daniel Akst summarises it like this:

(T)he book, the best business book of the year on leadership, is significant for one big reason: it is the avowed summa of a man who has been the nation’s premier management guru for decades. And at the heart of his new volume is the urgent recognition that above all else, leaders will have to pay far more attention to people from here on out. To do that, they may well have to rethink their business’s presumed purpose.

Open Strategy is about just what it says on the cover; what happens when you open up your strategy process to your employees, rather than having a small senior group do it in private. In large companies, doing strategy is usually a macho pursuit in which managers, mostly male, have a dick-waving competition:

However, the reality is that leaders often find it difficult to develop imaginative ideas on their own, shackled as they are by their conventional wisdom and groupthink. Encouraging their employees to sign up for a newly developed strategy is harder still, considering that they haven’t been given a say in how the strategy should be implemented. It’s therefore no surprise that between 50% and 90% of strategies fail... The authors boldly argue that a lack of openness is a bigger obstacle to success than the wrong strategic framework, a lack of intelligence, or poor consultants.

Beyond Collaboration Overload, by Rob Cross, ploughs a similar furrow, but from a different angle. It turns out that businesses have become so collaborative that they suffer from ‘collaboration overload’, which turns out to be a time-consuming problem. Theodore Kimmi summarises it like this:

Beyond Collaboration Overload earns its spot among this year’s best business books for several reasons. It disabuses us of the notion that collaboration per se is a good thing. It defines dysfunctional collaboration and identifies its many causes. It provides a host of research-derived tools and techniques for managing collaboration in ways that benefit people and the organizations they work within.

I was less convinced by this argument, although I havern’t read the book (let’s face it, how many business books are worth reading all the way through?). What was being described in Kimmi’s article were businesses that were apparently being collaborative but in a hierarchical structure. Better to fix the problem at source.

The Tech and Innovation title, Your Computer Is On Fire, is quite a left-field choice: an academic collection of essays written for STEM students. But:

The authors fearlessly dismantle the technology industry’s most sacred assumptions, forcing a rethinking of everything we’ve come to accept as true about our digital lives and the multibillion-dollar digital transformations going on inside our companies. Titles such as “Gender Is a Corporate Tool,” “A Network Is Not a Network,” and “Coding Is Not Empowerment” pull no punches... Your Computer Is On Fire succeeds by forcing us to adjust how we think and talk about the essential issues at the center of business and society.

Historically, at least from memory, this section has been Silicon Valley blah, so this does represent a change in the weather.

Oliver Burkemann’s book Four Thousand Weeks is something of an assault on the idea of time management, and the tyranny of the to-do list, and by extension, on some of the ideas about task-driven productivity. I’ve been meaning to write a piece about it on Just Two Things for a while. James Surowiecki suggests that it’s about more than work, however:

Although Four Thousand Weeks offers plenty of lessons about work, it’s also the year’s best book about consumer behavior. That’s not just because it has a lot to say about how the attention economy warps our experience, but because it’s a book about consumption in the deepest sense, a book about how we spend our time. As Burkeman puts it, in one of the book’s most haunting sentences, “When you pay attention to something you don’t especially value, it’s not an exaggeration to say that you’re paying with your life.”

Adam Tooze’ book, Shutdown, has had a lot of love this year, and apparently deservedly so. I probably don’t need to add to that here. But it’s worth noting Ray Avent’s conclusion here:

To survive this new era, in which old orthodoxies have been thrown aside and new rules apply, we will have to find a vision and a wisdom that has eluded us these past two years. It will not be easy. Tooze closes his book, once again, in ominous fashion, with the line, “We ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Even when we solve the medical crises, we will still have an economic crisis to solve. I’m probably going to read Shutdown at some point, but the book that jumped out for me here—partly because I’d not heard about it before—is Your Computer Is On Fire.

#2: Ghana’s legacy from Louis Armstrong’s flying pre-independence visit

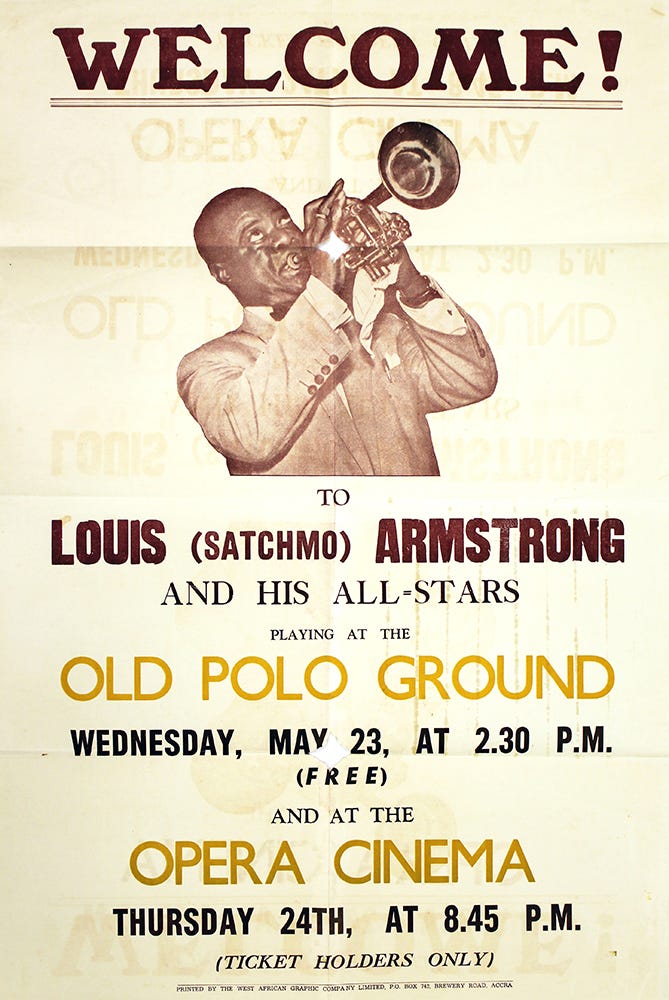

(‘Welcome Armstrong!’. Accra flyer, 1956. Source: Georgetown University Library.)

The trumpeter Louis Armstrong visited Ghana (then still known as the Gold Coast) 65 years ago, and the trip shaped both the country’s music and its sense of itself in the last few months before it gained its independence from Britain.

At the time, Armstrong was one of the most famous musicians in the world, and certainly one of the most famous black musicians. It was the first time he’d been to Africa, and he was greeted by huge crowds wherever he went. One lasting legacy is the sound of highlife music, Ghana’s distinctive sound.

This story is told by Laura Kiniry in an article in Atlas Obscura.

“There was more than just excitement in the region during Armstrong’s visit,” says Adrian Oddoye, co-owner of Accra’s +233 Jazz Bar and Grill, “it was euphoria,” he says of the scene captured in archival recordings … The trumpeter had arrived at the precise moment that the citizens of this soon-to-be independent country were reclaiming both themselves and their sound—one that played a pivotal role in establishing Ghana’s new national identity.

There’s quite a complex musical history that sits behind this. American jazz emerged from New Orleans in the first helf of the 20th century, but it was built around rhythms and musical patterns that had come from Africa:

Rhythms and harmonies derived from West Africa’s indigenous tribes made their way across the Atlantic with the enslaved people removed from Africa through ports such as Elmina Castle and Cape Coast Castle in Ghana. By the time of Armstrong’s 1956 visit, New Orleans jazz had already found its way back to West Africa. Swing jazz and highlife were the tunes of choice in local clubs catering to American and British allied troops stationed along the Gold Coast during World War II.

Armstrong was in the country for only 48 hours but ever hard working, played two concerts as well as a jam session with the local musician Mensah, the ‘king of highlife’:

Not only did their joint jam session propel Mensah and the highlife genre toward international recognition, but it also solidified Mensah as a leading voice in Ghana’s independence movement. The musician’s song Ghana Freedom became an unofficial national anthem.

The trip was funded by Armstrong’s record company and organised by the broadcaster Ed Murrow, who was producing a documentary about Armstrong and was interested in seeing how the trumpeter might react to the country. We don’t really know that, and as Kiniry points out, what we do know was largely mediated by white media, although it’s a matter of record that the following year he spoke out the American government’s failure to enforce desegregation in Little Rock.

And these two stories have a dark sequel. America’s civil rights failures meant a loss of reputation for the US across Africa at a time when many countries were gaining their independence. So the CIA, noticing the success of trips like Armstrong’s, funded a ‘jazz ambassadors’ programme that sent leading jazz musicians to play in Africa—musicians who didn’t know they were part of a State Department ploy. Four years later, Armstrong played an unwitting part in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo. But that’s a different story.

(Ghana flyer, 1956. Source: Georgetown University Library.)

j2t#230

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Before someone from strategy+business complains, there are some books by women authors among the two ‘honourable mentions’ in each section.