17 April 2023. Business (2) | Space

Changing business for the better // Robots are the future of space exploration

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Changing business for the better

On Friday, I discussed the types of businesses we need if they are going to be sustainable, and the gap between those and most of our actually existing businesses. I shared a model from Richard Normann that I suggested might help improve the analysis of this—shown again here:

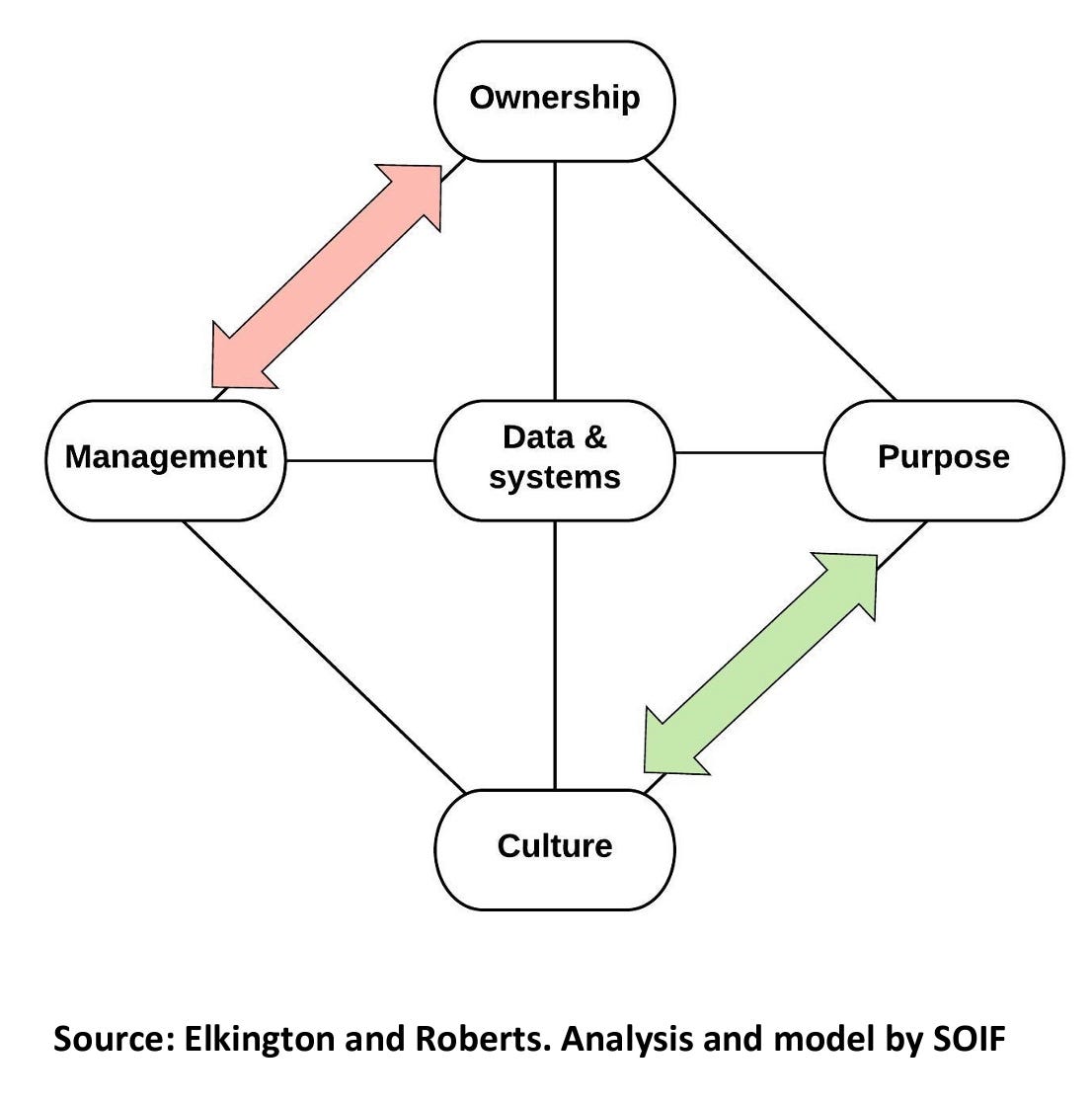

Today I’m going to build on all of this. Because this model has more value when different organisation functions are laid on top of it. Borrowing from and developing work done by the Tomorrow’s Capitalism project, one can simplify the organisation to five functions:

• Ownership

• Management

• Purpose/ citizenship

• Culture, and

• Data/Systems.

It’s also possible to map these five functions of the business onto the Richard Normann diagram.

In times of change, ownership and culture are likely to conflict with one another, and so is management and purpose. Similarly, ownership and management are likely to align as an axis that slows down change, while purpose and culture are likely to align as an axis that promotes change.

The reason for this is that ownership and management are both systems that are embedded in the business and its history. They are intended to be stable, and to provide structure, and this involves a degree of (partly necessary) “lock-in.”

In contrast, in times of change, purpose and culture are more fluid. They are rooted in values and attitudes, which change more quickly, and are also influenced more quickly by social change outside of the business. Data and systems, which are typically products of earlier “theories of the business”, and the assumptions embedded in it, sit in the middle of these tensions, evolving to fit new demands, always behind the curve.

As a result, the value commitments that leaders and managers choose to make are critical and often symbolic. They are ‘enacting’ the culture and purpose they want to see.

The problems caused by current models of ownership is one of the recurring themes in the current literature about new forms of capitalism. There are good reasons for this, which I’ll come back to in a moment. But in the normal workings of a business, ownership should be an anchor on change. Shell’s research on long-lived companies, popularised by Arie de Geus in The Living Company, found that almost all of them were conservative about finance.

Similarly, the management and structure of a business is designed to maintain its integrity and ensure its continuing existence. All organisations are ‘dynamically conservative’ (in Schon’s phrase). They respond to shocks with the minimum amount of change needed to ensure their continuing viability.

They therefore also tend to cling on to outmoded models of the world, and outmoded notions of viability. Even when actual data and performance elsewhere shows that these models are both wrong and no longer useful, they are reluctant to change. Businesses that are actively committed to change need to find ways to use purpose and value commitments to modernise structures and keep owners onside.

It’s worth exploring how this works in practice, with a couple of examples.

Food manufacturer Danone was founded with a mission that combined economic and social purpose. When its North American subsidiary acquired WhiteWave in 2016, it incorporated the combined business as a b-corps. This meant that it could enrol its social purpose in its legal corporate structure. This allows purpose to signal to ownership.

The company’s chief executive also told its North American executives that they would stop selling foods with GM ingredients in them. The management team achieved this in two years despite some initial scepticism about timescales.

This represented a value commitment that used culture to drive change in management. But it doesn’t always work. It’s possible that Richard Browne’s attempt to move BP to “beyond petroleum” was a value commitment. But since it was backed by little in the way of meaningful action—not much in the way of “commitment”, in other words—it was read instead as greenwashing.

The legacy of the idea of ‘shareholder’ capitalism is that ‘owners’ have been privileged above other stakeholders. The combination of lightly regulated investment and digital technology has amplified the interests of owners, and created a financialised business sector.

The business literature is full of reasons why this is a bad idea. As Martin Wolf of the Financial Times observes: companies

“serve the interests of those least committed to it, while control is also entrusted to those least knowledgeable about its activities and at least risk of damage by its failure.”

In her book, Eve Poole quotes research that says in the age of high frequency trading, ‘owners’ own their shares for less than a minute, on average. A share conveys certain rights to the holder, but not the rights of ownership. This skews, hopelessly, the incentives in the market. It benefits short-termist financially driven businesses at the expense of others.

And as the economist Michael Pettis notes, it creates balance sheet incentives around debt that make it hard for prudent businesses to compete. It creates the conditions of predation.

Businesses that are trying to play by different rules—even large ones—can’t escape from these dynamics. Again, looking through the model at a well-known example, the short-lived bid by Kraft Heinz for Unilever is a case in point.

Kraft Heinz, owned by 3G Capital, has an aggressive M&A driven model which squeezes costs out of acquisitions and returns money to shareholders. It seems to produce short term improvements in returns and a long-term decline, which should be to no-one’s surprise.

Unilever’s model was about long-run, purpose-driven growth. But facing down the bid wasn’t a cost-free exercise. The price of getting shareholders to support the Unilever Board was a a share buyback and more aggressive cost-cutting. At the time of the bid, Unilever’s long-run share price growth had been comfortably greater than that of Kraft Heinz. But both these measures would reduce growth. When ‘owners’ meet ‘purpose’, in the current model, ‘owners’ win.

Broadly speaking, this all comes back to a case for different rules governing the intersection of finance and businesses. The joint stock company—a creature of the early stages of modern capitalism—is, in the way that it is currently constituted, no longer fit for purpose. In an age of instantaneous share transactions, companies need a buffer to protect them from what amounts to hot money. The thinking behind B-corps is one way to create that buffer—purpose, in effect, gets written in to the company’s legal articles of association.

But on its own, this is not enough. We need to change the rules of finance. I know that there are people working on this who know much more about it than I do. I’d love to hear from you.

2: Robots are the future of space exploration

I’ve been doing a project on the future of space, which I can’t say anything much about at the moment. But one of the articles I came across when I was involved in the research was by Martin Rees, the British Astronomer Royal, and Donald Goldsmith. It was based on their recent book, and it argued that people are more or less superfluous when it comes to future space exploration.

(Artist concept of the NASA Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover. Picryl, CC0)

Future exploration, they suggest, will be down to robots.

And while we know that robots continue to be terrible at some things, such as playing football, they are now able to perform space exploration tasks at far lower cost and with far lower risk, then humans, and will continue to get better at them:

Our robot explorers have visited all the sun’s planets (including that former planet Pluto), as well as two comets and an asteroid, securing immense amounts of data about them and their moons, most notably Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus, where oceans that lie beneath an icy crust may harbor strange forms of life... Each of these missions has cost far less than a single voyage that would send not robots but humans, which in any case remains an impossibility, for the next few decades, for any destination save the moon and Mars.

They suggest six reasons why we are still attached to the idea the future of space exploration is about humans. These are: tradition; engagement; adventure; inspiration; ownership; and wealth (e.g. space mining). As they note, the first four of these stem from deep-seated human attitudes (they don’t use language about deep-rooted narratives about space, but they could have done).

The last two, on the other hand, are more linked to

“the long history of conquest and exploitation of Earth’s resources, whose long and effective history has profoundly altered our planet”.1 —FN They note, in brackets, that “the best argument against long-term plans to “terraform” Mars by creating a more Earthlike environment remains the sad results of our “terraforming” of Earth.

Although these are the worst reasons for going into space, they could easily be done by robots, and entrepreneurs, and arguably space mining will only be done, if it ever happens, by robots.

Science could also benefit from this:

astronomers would dearly love to have a giant radio telescope on the far side of the moon, which would screen out terrestrial radio interference marvelously well. In the near future robots could build this telescope more efficiently and much more cheaply than humans.

And, indeed, astronomy provides the model here. Rees and Goldsmith contrast the expense of the low orbit Hubble telescope, and its multiple manned repair missions, with the lower cost of deep space telescopes such as the James Webb. These missions cost about a billion dollars each:

the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute said that the cost of the five repair missions would have paid for seven replacement telescopes.

NASA has a list of “20 breakthroughs from 20 years of the International Space Station”, and it turns out that this is a useful checklist for the value of robotics over people:

Seventeen of these dealt with processes that robots can perform, such as launching small satellites, the detection of cosmic particles, employing microgravity conditions for drug development and the study of flames, and spaceborne 3-D printing. The remaining three dealt with muscle atrophy and bone loss, growing food, or identifying microbes in space—important for humans in that environment, though hardly a rationale for sending them into space.

Of course, much of the rationale for space exploration is not driven by rationality. I don’t think I’d fully appreciated, before I started the space project, the extent to which space exploration was bound up with ideas of modernity—that human progress is inextricably tied up with ideas of expansion.

Indeed, my son pointed me towards an interesting conversation between anthropologists and an indigenous peoples in the Amazon in which the anthropologists walked the Amazonians through various features of Western civilisation.

When they told them about astronauts landing on the Moon, the Amazonians hated it, because the Moon was a sacred object in their culture. I’m not sure how they would have felt about a giant radio telescope on the dark side of the moon, even if it had been built by robots.

Other writing: fiction and music

I’ve posted a couple of fiction reviews on my blog ‘Around the Edges’ in the past couple of weeks. The first is on Jonathan Coe’s book Billy Wilder and Me, which I read as an exploration of what happens when an artist loses touch with their audience. The other was G. Willow Wilson’s Alif the Unseen, set in a modern fictional Arab state. An extract:

The other thing I like about the book is that one of the lead characters is a girl who has chosen to wear a niqab ever since she was at school, even though her classmates didn’t, and it engages seriously with the complexities of this. In fact, Alif the Unseen is one of the few novels I’ve read by a Western author that takes Islam seriously.

I also have a review of a gig by Rachel Waterson’s side project, Unthank:Smith, at the folk music site Salut!Live, if you are interested in contemporary British folk music.

j2t#446

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

They note, in brackets, that “the best argument against long-term plans to “terraform” Mars by creating a more Earthlike environment remains the sad results of our “terraforming” of Earth.”