16 November 2024. Resources | Poetry

Smarter resource use over time makes the circular economy work better // After Tahrir: the work of poet Mostafa Ibrahim. [#616]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: Smarter resource use over time makes the circular economy work better

I think the first time I thought seriously about the notion of the circular economy was in 2002, when I bought Cradle to Cradle, by William McDonough and Michael Braungart. By that stage they had been collaborating for a decade. (The concept goes back at least to 1976.)1

This is their summary of the circular economy:

Everything can be designed to be disassembled and safely returned to the soil as biological nutrients, or re-utilized as high quality materials for new products as technical nutrients without contamination.

The physical copy of the book that was sold was also a ‘technical nutrient’ that could be broken down and used in other processes. It was heavier than a book made from trees, glossier, and slightly strange to the touch, even futuristic.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The second chapter of Cradle to Cradle, ‘A Question of Design’, had a rundown of the design principles that underpinned the socio-technical systems of the Industrial Revolution—on the basis that ‘the purpose of a system is what it does.’ None of this has changed since they wrote it:

Design a system of production that

• puts billions of pounds of toxic material into the air, wa-ter, and soil every year

• produces some materials so dangerous they will require constant vigilance by future generations

• results in gigantic amounts of waste

• puts valuable materials in holes all over the planet, where they can never be retrieved

• requires thousands of complex regulations-not to keep people and natural systems safe, but rather to keep them from being poisoned too quickly

• measures productivity by how few people are working

• creates prosperity by digging up or cutting down natural resources and then burying or burning them

• erodes the diversity of species and cultural practices.

But the thing about changing our current industrial system into a circular economy is that—well, it’s hard. You need to connect up companies who need as their raw materials the by-products of your production processes, and typically they’re not in similar industrial sectors or business ecosystems.

And you need to design everything to be disassembled (and this is beginning to happen). And, however good your disassembly processes are, you’re never quite going to get to 100%. There’s always going to be something that can’t be reused or returned to the soil. We never quite eliminate the notion of ‘waste’.

So this is a longish introduction into a piece by Hannah Ritchie at her Sustainability by Numbers where she explains that the circular economy might work better than we have previously thought. If you don’t follow her work, she’s strong on the technical aspects of transition, less strong on the politics of it.

The reason: we’re getting better at using resources over time:

[W]e will need a large ramp-up period of mineral extraction as the world shifts to renewables, batteries, and electric cars, but the hope is that we then reach a better equilibrium where materials for new solar panels and turbines are coming from old ones that have reached the end of their life. Total circularity seems unlikely, but maybe we could get close. But I think this circularity discussion actually underestimates how much of a difference low-carbon technology could make in the model of the resource economy.

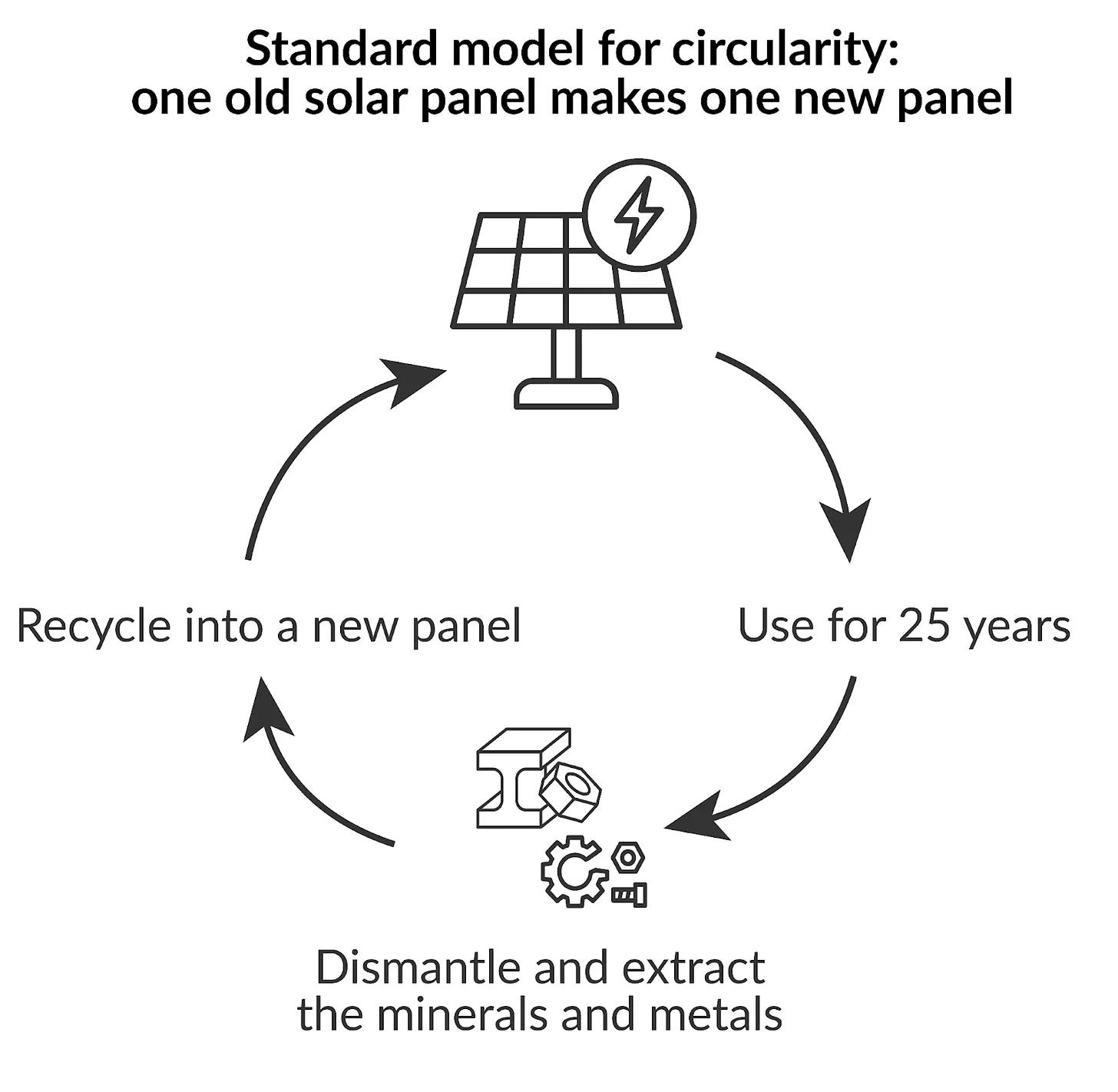

I think there’s three diagrams and charts in her piece that underline her point. The first is the traditional idea of the circular economy.

(Source: Hannah Ritchie: Sustainability by Numbers)

In this model, the materials that are disassembled from the solar panel that is being taken out of service are put into a replacement solar panel. One equals one. Or—because of leakage in the circular system, one probably equals a bit less than one.

But over the 20-year life of that solar panel, we’ve got a lot better at making solar panels. The 2024 solar panel is a lot more resource-efficient than the 2004 solar panel was.

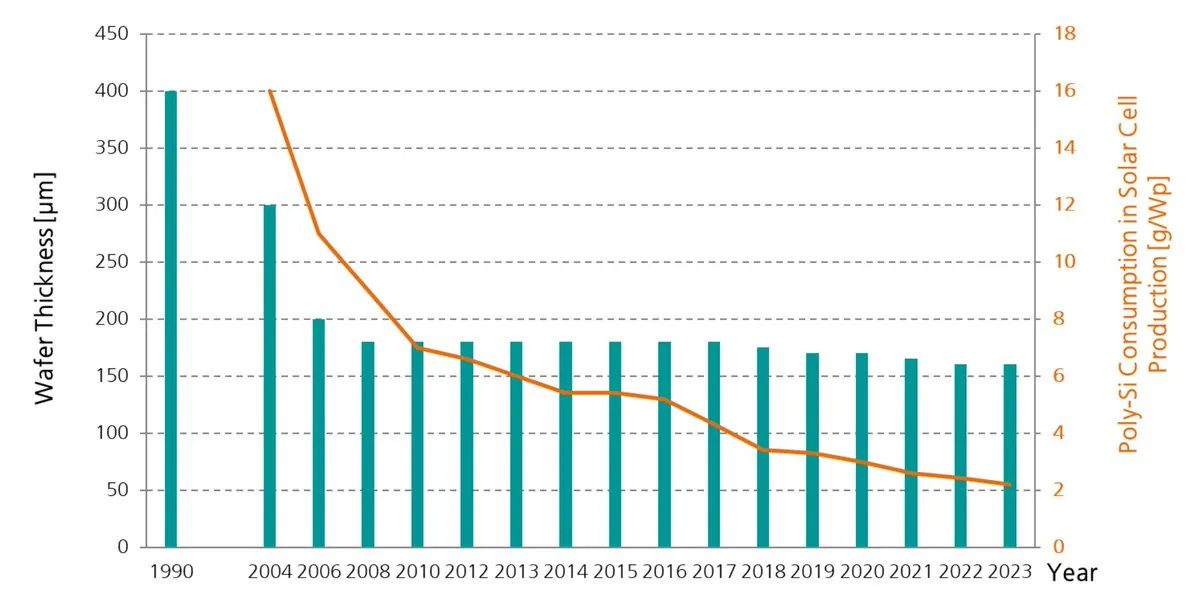

And in fact, the German Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, which is a knowledge transfer institute that connects academia to industry, has data on this.

(German Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, via Sustainability by Numbers).

Ritchie has had to focus on the data on the resource use of polysilicon and silver, because the data for the use of some of the other materials in solar panels is hard to come by. But it seems like a reasonable assumption that in general production would get more efficient.

Economists always talk about economies of scale as the factor that drives costs down, but at least as important are ‘economies of experience’. These are described in Wright’s Law, which is the best explanation of why costs fall over time.2 A summary of a 2012 paper from the Santa Fe Institute summarises the model that sits behind Wright’s Law as “learning by doing”.

Over 20 years, in fact, the same amount of resources is 6-8 times as effective as it was in 2004.3

With the 16 grams of polysilicon, you could have made one watt of solar power in 2004, 2 to 3 watts in 2014, and 6 to 8 watts today... Or take the example of silver. The amount of silver needed per watt of solar fell by 20% for every doubling of global cumulative capacity. That’s very similar to the “learning curve” of solar costs: every doubling in cumulative capacity led to a 20% drop in costs.

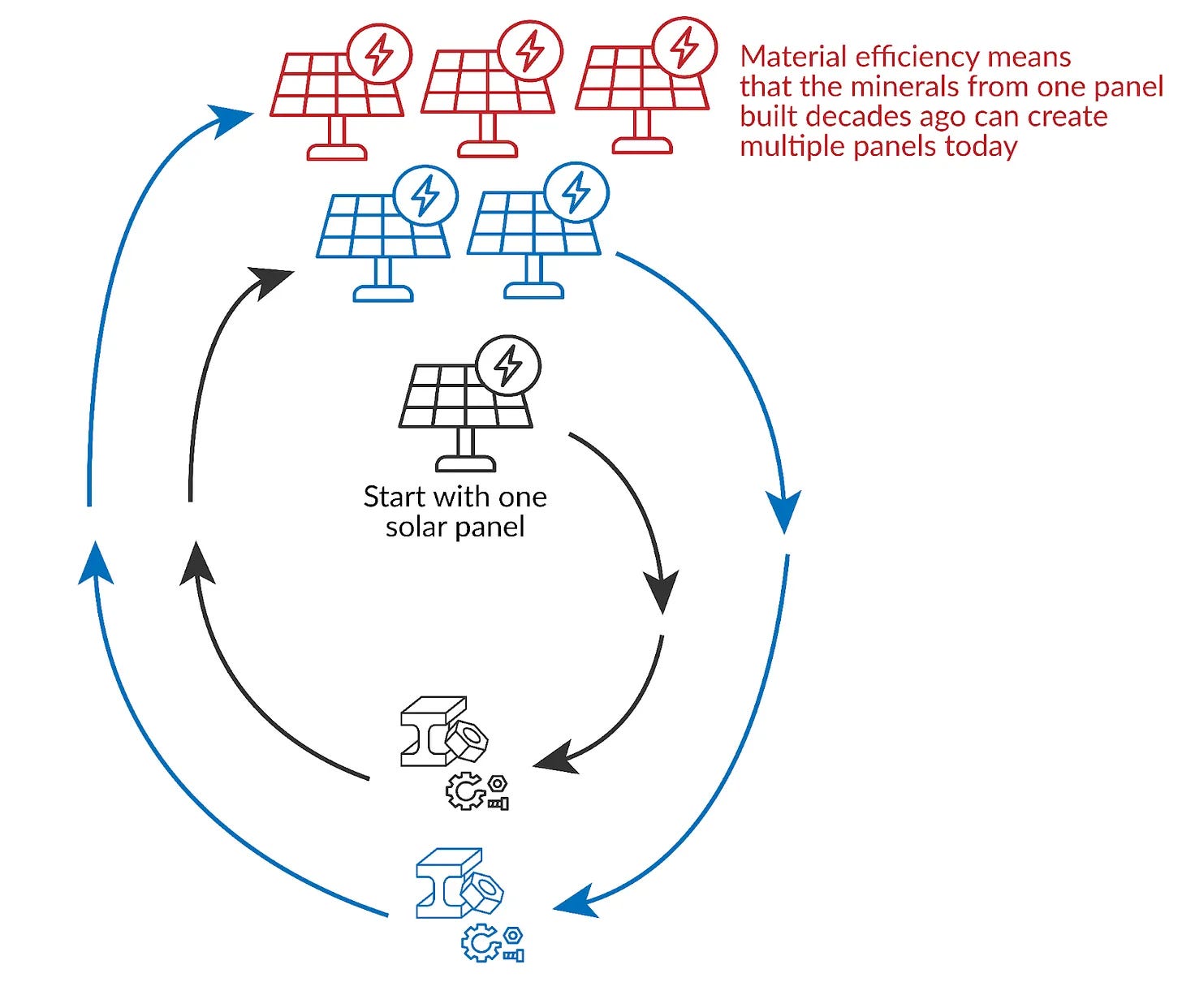

Heres what that looks like in her schematic:

(Source: Hannah Ritchie: Sustainability by Numbers)

Obviously, there’s a point where this resource effect starts to slow, but we’re a long way away from that at the moment when it comes to solar panels:

By the time a 2010 panel reaches the end of its life — in 2035 or 2040 — silver consumption might be as low as 5mg. In this case, it’d be enough for 10 panels (or “only” 8 if the recovery rate is 80%).

This does depend on recycling technologies continuing to improve.

She also notes that the difficulty in getting hold of some of the data is an indication of a market that is still developing fast. And from her perspective, that’s a good thing, not a bad thing;

It means things are moving quickly. But it also means that a lot of the literature is too pessimistic, using outdated assumptions on costs, and the amount of materials we’ll need in the future.

2: After Tahrir: the poet Mostafa Ibrahim

LitHub has published three newly-translated poems by the Egyptian poet Mostafa Ibrahim. He’s in his 30s now, and came to prominence as one of the voices of the January 2011 revolution. People would, apparently, graffiti lines from his work on walls and in public spaces.

(Mostafa Ibrahim: Source: Poetry Translation Centre)

I’m going to share one of the three poems below, but they come as a set, and they have a cumulative effect, so even if you’re only half-interested in poetry I recommend going to the LitHub article and reading them.

The thing that caught my attention, though, was the very personal description by the translator, Abdelrahman ElGendy, about his relationship with Ibrahim’s work, in particular his 2013 poetry collection The Manifesto:

It was also the text that sustained me in prison.

For over six years between 2013 and 2020, I was a political prisoner in Egypt. When dark thoughts swirled and clawed at my brain in prison cells, I turned to poetry. Along the years, Ibrahim’s Manifesto, in particular, became my sacred literary scripture. In the quiet of the night, I would let its lyricism hold me and mourn alongside its verses.

Any book published in 2013 by someone who had supported the revolution in Egypt would be more bitter than sweet, and so it proves:

The collection [recalls] the once fervent pulses of revolutionary vigor, now stilled by defeat. It oscillates on the spectrum between bleak realism and tender crests of romanticism. Each poem unfurls as a whisper, a mirror held up to the remnants of a crushed uprising. Through meticulous dissection, Ibrahim probes the skeletal remains of shattered dreams and fragmented loyalties among comrades who once shared a square, a sidewalk blanket, and a barricade.

His work, says ElGendy, “encapsulates Egypt’s 2011 Tahrir generation.”

Tofranil 50 is an anti-depressant. The next two poems in the sequence are called ‘Tofranil 75’ and ‘Tofranil 100’, respectively.

Tofranil 50

I always hold

out till the end: cards tossed

in games of chance,

answering roll call,

booking a seaside flat in Baltim.

Among my friends, I’m the last

to repent, the last

to rise from prayer, last

for shots in the school queue.

When it’s time for Qs, I’m the final

A

I’m an old scar, once

beneath long sleeves. The world

cursed me, and I cursed

back tenfold. I loved people

till I turned six. Then

they made me forget

who I was. I can’t recall

when it began. My cup of coffee

never empty, never-ending talks

with God. I’ve never trusted

any girl but Reem, and now

I’m not sure I can. Last time

I saw her, she was moving. A taxi

stuffed with suitcases replacing

her. Faces of strangers

I couldn’t name. Reem

was my age back then, but now

she’s younger. She knows

I age too fast, recall

too much. I remember

time down to the second,

like the day we buried

my sister. I remember the day

better than I remember her.

Some nights vanish in full, but

I can picture our Qasr El-Nil

flat, though the faces

of tenants slip away.

I’ve never forgotten

a place. Even Shady’s

house. I visited

once. A picture frame

by the door, his middle

school face, a faint mustache

smudging his lip. My back

stoops by all I carry. Sorry

to ramble, eat your time

and mine. My mind

is thickening. I need

to sleep, go home.

Thanks for the session—

When’s our next appointment?

We’ll meet soon.

I’m leaving now.

Goodbye.

OTHER WRITING: MUSIC

The Scots electro-folk band Niteworks are calling it quits on their career tonight in a big long-sold out gig in Glasgow. For me, they are one of the few successful attempts to meld dance music and folk.

I wrote a short piece about them at my Around the Edges blog. Here’s an extract:

They grew up playing ceilidh music and listening to dance music and they wanted to combine the two. Another Skye musician, Mylo, was an influence (see his 2004 record Exterminate Rock & Roll), as was Martyn Bennett, along with a dance festival that ran on Skye in the 2000s.

In a recent interview with Scots Magazine, the band’s piper and guitarist Allan MacDonald said,

“It felt natural to take the more traditional music we were making in various ceilidh bands and shape it into something more dance-y to reflect what we were listening to.”

j2t#616

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

In other words this is another example where we knew what we had to do 50 years ago but didn’t take it seriously enough to do it.

In case you’re wondering: Moore’s Law is a special case of Wright’s Law.

Ritchie has had to make some simplifying assumptions to translate resources into watts, but they are reasonable assumptions to make.