16 June 2025. Difference | Nudge

Sly Stone and the celebrity of difference // Giving up on ‘nudge’ theory// Bloomsday [#J2T 642]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Sly Stone and the celebrity of difference

(Photo: Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

About halfway through Amir ‘Questlove’ Thompson’s music documentary Summer of Soul, Sly and the Family Stone are about to appear on stage. It’s not quite as simple as that. As one of the other performers recalls—in an interview filmed years later—just because Sly had been announced it didn’t mean that he was going to appear straightaway.

But: he does appear, and seeing the band there, in Harlem, in 1969, at pretty much the height of their fame and reputation, you can see immediately the impact they had.

The band appeared at the first of the six concerts that made up the Harlem Cultural Festival in Mount Morris Park that summer, two months before headlining at Woodstock.

As Rolling Stone said in its paywalled obituary of Sly, who has died at the age of 82,

At the peak of his success, when hits like “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People” were high on the charts, the wildly inventive musician and singer presented a glowingly optimistic image in step with the times, bringing together Black and white audiences, uplifting crowds with electrifying shows. But the unpredictability that was the core of his genius gave way to a long decline, as his personal demons destroyed what he had once been.

Ted Gioia, normally a sharp commentator on music, tells a version of the same story in a republished review of Stone’s autobiography. It’s a familiar music industry trope—too familiar, really—and I’ll come back to the notion of “unpredictability” and “genius” later on.

But the main point here is that It’s easy, after more than 50 years, to overlook the huge cultural impact Sly Stone had in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The band was racially mixed—one of the two white musicians jokes on the film that they were the only white people in Mount Morris Park that day. It had women in the lineup who played instruments rather than just singing backing vocals. They were a blaze of colour: psychedelic clothes may have been common in white rock music by 1969 but in black music stage outfits still tended to be regimented.

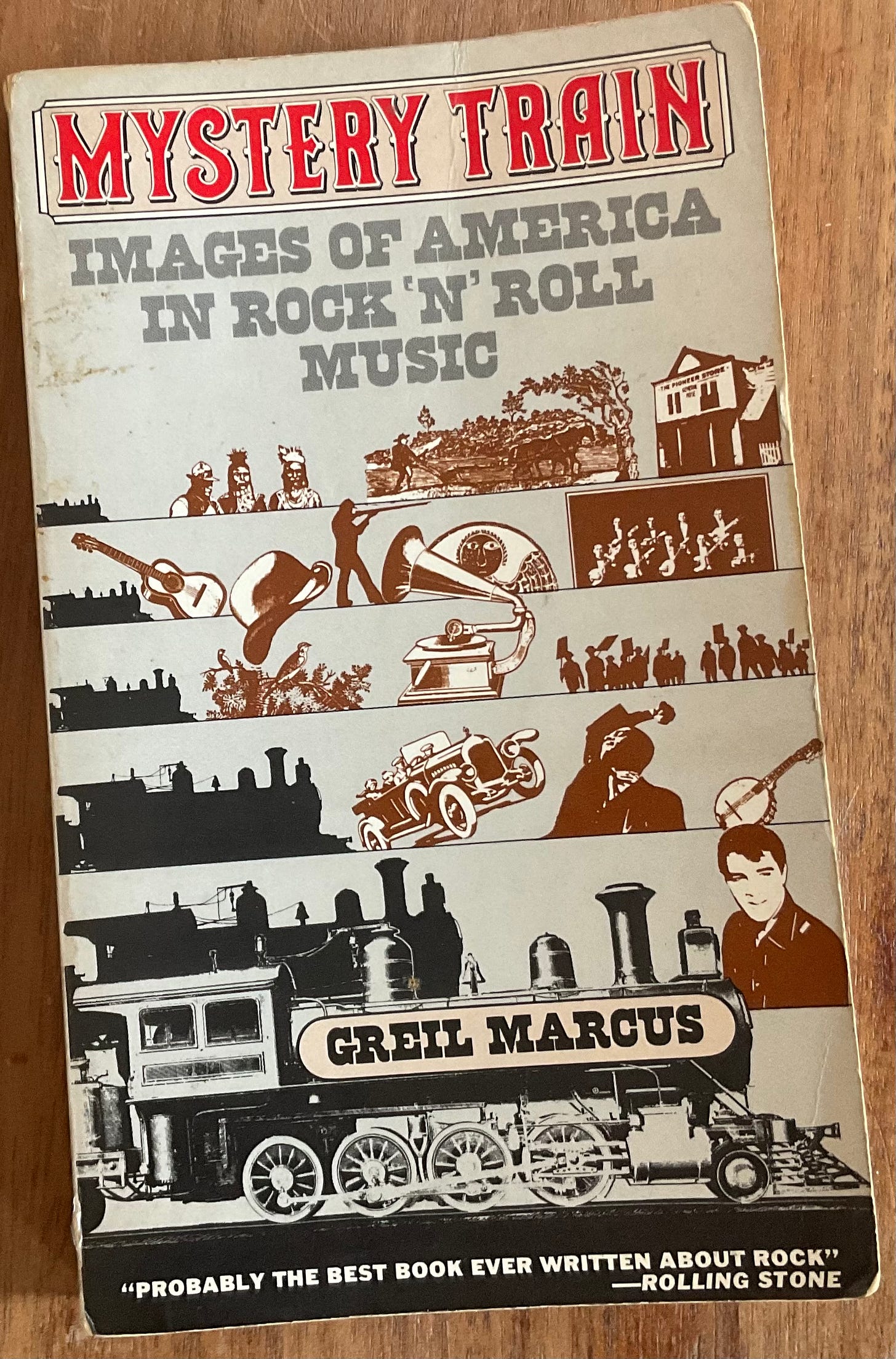

And then there was the music. In Greil Marcus’ words, in his 1976 book Mystery Train:

In the manner of the very greatest rock 'n' roll, Sly and the Family Stone made music no one had ever heard before. In moments you could catch echoes of Sam Cooke, the Beatles, a lot of jazz, and even a little surf music... The whole was something other than its parts, perhaps because what came across was not simply a new musical style, though there was that, but a shared attitude, a point of view: not just a brand-new talk, but the brand-new walk of young men and women on the move. [81]

As Anil Dash says in a short piece published after Sly’s death, of seeing Sly play years later,

I don't think I've ever seen a room feel greater relief than watching him tear into "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again)" and feeling the frustration, anger, and resentment of everyone around him melt away from the sheer force of the joy and pure undeniable propulsive funk of that song. And there's no better example of the power of Sly's gift.

And one of the reasons that all of this struck a chord with me was because I had the privilege recently of facilitating a workshop for one of the Max Planck Institutes on the future of difference, and, for me, Sly Stone represents a moment where difference is created.

I’m pretty sure that the first time I came across Sly Stone, in an age when music wasn’t on tap, was in Mystery Train, which I probably bought a couple of years after it was published.1 Marcus has a way of writing about music that is both allusive and metaphorical, which is not to everyone’s taste. In Mystery Train he starts out with the blues players Robert Johnson and Harmonica Frank, before moving on the longer essays about contemporary performers he considers have a connection to them: The Band, Sly and the Family Stone, Randy Newman, and Elvis Presley.

(Photo: Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This might seem like an eccentric selection, but the book works.

Metaphorically he links Sly Stone to the blues song about Staggerlee, the bad black man who lived life on his own terms and seems untouchable—until he’s not.

Sly Stone had talent to burn. He had been a teenage prodigy, working while still a teenager as a music producer and a disc jockey in suburban California.2 By the late ‘60s, as Gioia notes,

Between 1967 and 1971, Sly and the Family Stone were constantly in the airwaves—with five top ten singles, including three that reached number one on the chart... Sly Stone had a whole new sound. He called it psychedelic soul. And every record label wanted its own version of it.

It’s hard to overstate his influence: Miles Davis, for example, listened to his music over and over while working on Bitches Brew.

As we move through the ‘70s and beyond, Stone’s behaviour becomes more erratic, he becomes more dependent on different types of drugs, and he becomes more unreliable. He ends up in rehab, he runs out of money.

As it happens, Questlove has, with perfect timing, completed and released a full length documentary, Sly Lives!, on Sly Stone’s career. There’s a 12-minute segment from ABC’s On the Red Carpet slot of him talking about the film, with some great footage. In the short clips, Stone comes across as both whip-smart and reflective.

The subtitle of the documentary is The Burden of Black Genius, and in the interview Thompson is keen to reject the idea of the “troubled genius”.

Instead he points to the violence and trauma that were swirling around in America at that time, and which sometimes touched on the band directly. Thompson notes that many of his interviewees, now in their 70s, had never really processed that violence until he asks them about it for the film:

A band member shared with me a rather disparaging story about getting pulled over by the police, and when they’re describing what happened to Sly, it’s one of the most horrific things I’ve ever heard in my life... Guns were in people’s temples... and when I said, ‘What happened after that?’, they just shrugged it off. ‘We got back on the bus and then we headed to Cleveland and we did a show’.

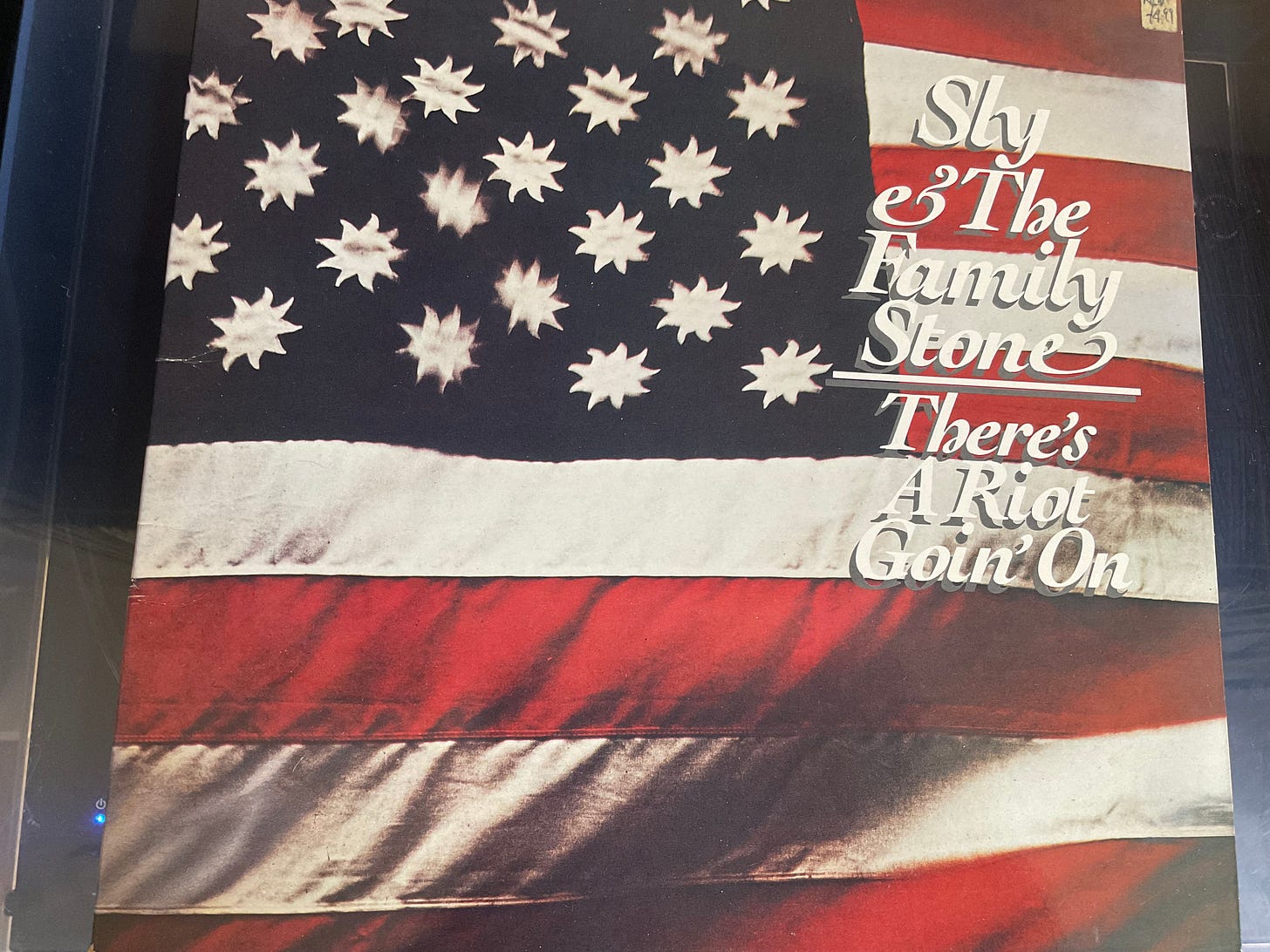

If Stone’s early records had felt light and uplifting, albeit with a touch of irony, his masterpiece is There’s A Riot Going On’, released in 1971. It’s a lot darker.

The date is important. In America’s endlessly racially charged politics, the political gains made by the civil rights movement in the 1960s were already being rolled back, as has happened several times since then. One marker of this was the FBI’s sustained attack on the Black Panther Party, which assassinated some leaders, such as Fred Hampton, imprisoned some, and drove others into exile. George Jackson’s killingin San Quentin, shot in the back in 1971 “while trying to escape”, was part of the same pattern.

Mystery Train was written while these and other related events were still fresh in the mind, and this is where Greil Marcus goes with his story. I’m not going to try to distil a 40-page essay here, but an extract might help:

The record was no fun. It was slow, hard to hear, and it didn't celebrate anything. It was not groovy. In fact, it was distinctly unpleasant, unnerving...

'There's a riot goin' on’ was an exploration of and a pronouncement on the state of the nation, Sly's career, his audience, black music, black politics, and a white world. Emerging out of a pervasive sense, at once public and personal, that the good ideas of the sixties had gone to their limits, turned back upon themselves, and produced evil where only good was expected, the album began where "Everybody Is a Star" left off, and it asked: So what? [83]

Greil Marcus traces a cultural thread of how Riot infused black film and music culture in the 70s, although I don’t have space to explore that here. But he’s clear that in making the record, Sly Stone has reached some kind of limit:

[It’s] the confession of a man, speaking for more than himself, who has been trapped by limits whose existence he once would not even admit to, let alone respect: trapped by dope; by the weakness behind a world based on style; by the repression that sent black men and women into hiding, into exile, into the morgue; by the flimsiness of the rewards a white society has offered him. [84]

Perhaps the clearest indicator of this is the final track on the record, ‘Thank you for talking to me, Africa’, which a remake of ‘Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again)’, slowed right down, the funk all but stripped out of it.

What I take from the story of Sly Stone is that societies can only absorb so much new difference at any one time, especially if that difference attacks or unsettles existing privilege or power relationships. It’s a dispiriting conclusion.

It was Anil Dash’s piece that prompted me to think more about what Sly Stone did, and and what happened to him afterwards. As Dash says:

It's hard to explain what Sly Stone was in a contemporary context. We have witnessed the ascendence and current dominance of a decades-long effort to dismantle the vision of racial and gender harmony that Sly invented and advanced in popular culture. But they only fought back against because he kicked that door open almost single-handedly... For all his flaws and foibles, this was a brave man. He changed things.

2: Giving up on ‘nudge theory’

I’ve always been sceptical of ‘nudge theory’. It’s an essentially neoliberal idea, although I’m not sure that the academics who developed it would recognise this description. It’s a neoliberal idea because it proposes, broadly, that the best that governments can do is to change the decision frameworks of individuals by fiddling with the settings within which they make what are essentially consumption decisions. It ignores the role that governments or agencies might be able to play in changing systems or structure. I also wonder about the ethics of it.

So I was pleased to see a recent paper in Behavioural Public Policythat proposes a more collective approach to this: ‘boosting’, not ‘nudging’.

I should probably back up a bit. ‘Nudge theory’ has been floating about for a while until it was formulated in a 2008 book by the Chicago academics Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. In the following years, a number of governments set up ‘nudge units’, including the UK.

Wikipedia has a pretty good summary of the approach, and of some of the controversies, which includes this extract from Sunstein and Thaler’s book:

A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.

Describing this approach before they critique it, the paper’s authors—Hertwig, Michie, West, and Reicher—characterise it like this, in yet another example drawn from public health:

To encourage healthier diets, for example, nudging steers clear of instruments like banning products, restricting advertising, or increasing costs through taxation... By rearranging products so that healthier options are more prominently featured and easier to access, nudging aims to direct people towards choices that are in their long-term best interests.

They also summarise the reasons that this approach is popular with policy makers:

nudge policies can be cost-effective, because they are usually cheap;

it appeals to governments opposed to regulation;

it doesn’t require governments to confront corporate interests;

it can be used to absolve governments of their failure to address collective or social problems; and

it aligns with politicians’ general views of the public, which often portray individuals as cognitively and motivationally deficient.

Since the Nudge book has come out, many nudge-based approaches have been researched, which is one of the benefits of an approach that basically comes out of behavioural science. If there’s a theme to this research (I say, vastly oversimplifying) it is that nudge approaches to change tend to have less effect than is initially claimed for them.

A lot of the thinking that sits behind ‘nudge’ is the whole range of behaviours that come under the general headings of ‘cognitive bias’. This links to a version of policy that is about making good “human deficits”—both cognitive deficits and motivational deficits; people can’t, in short, be trusted to do the right thing.

But this leads to an individualistic focus, typically at the point of consumption, which is one of the reasons I described ‘nudge’ thinking at the top of this piece as being a neoliberal idea. If my local Sainsbury’s is busy removing fresh food from the shelves to replace it with more profitable but less healthy processed food (as they visibly are) all the nudging in the world isn’t going to help.

And—without extending the underlying argument in the paper much beyond that of the authors—there’s a trust problem in there. Nudging is a form of cognitive trickery:

Governments basing policy on an individual deficit model which assumes that people are neither willing nor able to make good choices are unlikely to use strategies known to build shared identity and trust, such as listening to the public, engaging with them, co-producing policy, and showing respect.

What the paper proposes instead of ‘nudging’ is ‘boosting’:

Boosts are interventions designed to improve people’s competences to make informed choices that align with their goals, preferences, and desires.

This has been a live argument in the field for a few years now, and one of the main reasons for proposing boosting is that it respects human agency. In the version in the paper they are keen on different forms of literacy: digital literacy, risk literacy, financial literacy, health literacy, and so on.

Some of this language causes some concern to me. It sounds a bit like ‘nudge-plus’. I’ve been in more workshops than I can remember where people who work for financial services companies have suggested that what their customers need is more financial literacy, rather than having access to more straightforward products that are simpler to understand the benefits of.

All the same, the researcher connect ‘boosting’ to maximising ‘competences’:

Boosting involves more than just enhancing people’s competences; it also means shaping the environment to maximize individuals’ ability to use those competences.

I’d expected to see Amartya Sen in the bibliography, since I have some time for his human capability model, and this feels like it is in the same space, but the researchers hadn’t made that connection.

But the main point that underlines the paper is that the scale of our current crisis is such that we don’t have the time to rely on trivial interventions such as nudging. We need behavioural tools that promote trust and develop agency:

The concept of agency—and the recognition that people are empowered to make changes when they act together—marks a critical dividing line between approaches to behaviour change. The problem with the individual deficit model of the nudge approach is that it merely tweaks behaviour at the margins.

I’d go at least one step further here, I think. The unwillingness of governments to take steps against corporations and other organisations that are visibly causing harm is one of the factors that is reducing trust in politics and politicians—which undermines that ability of political parties to work with people to shape necessary change.

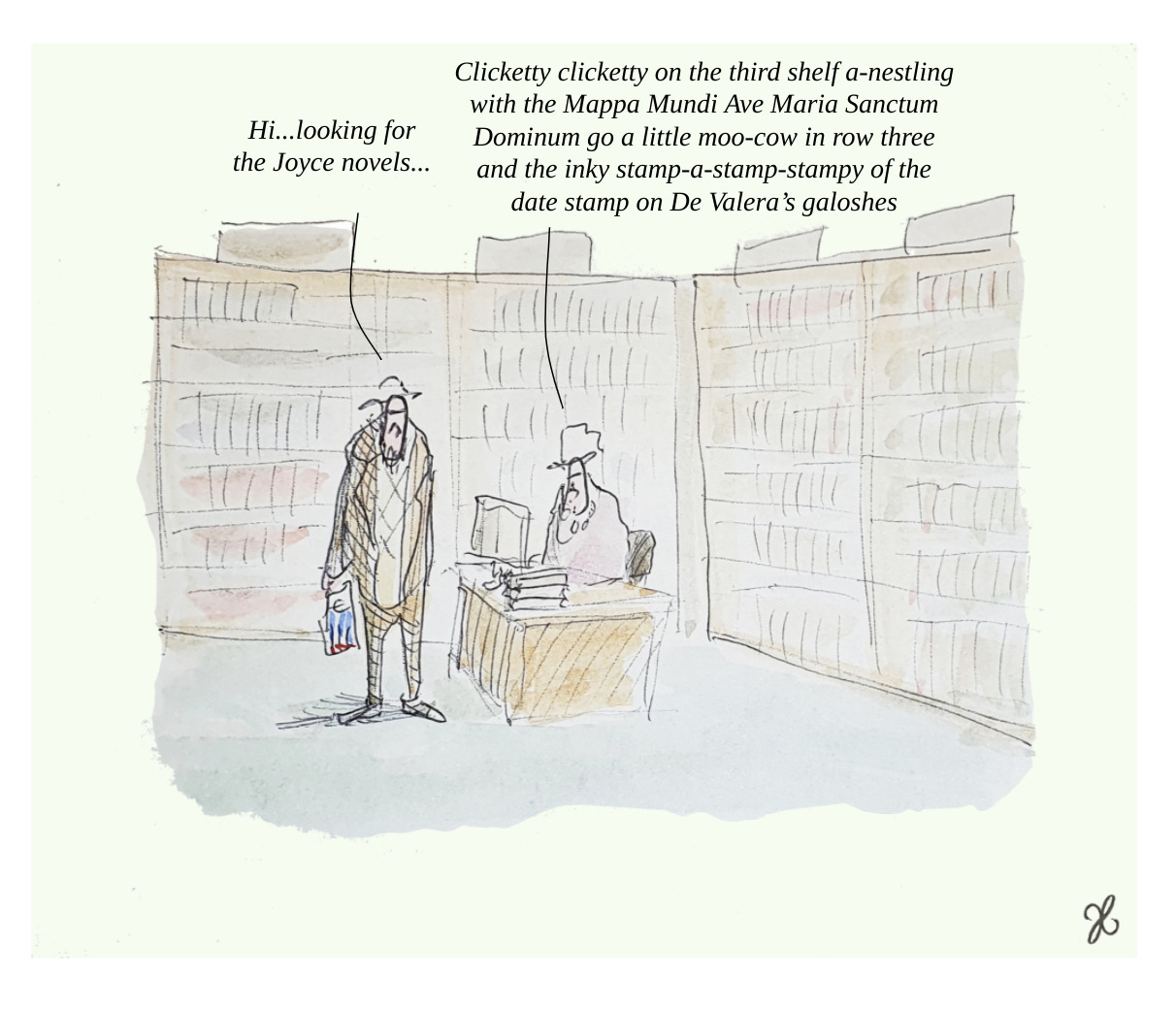

AND ONE MORE THING: BLOOMSDAY

It’s Bloomsday today—the day on which the action in James Joyce’s novel Ulysses unfolds. And to mark that, and to remember my late colleague Jake Goretzki, here’s one of his ‘bookshop’ series of cartoons, this one about Joyce.

((c) Jake Goretzki)

j2t#642

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Looking at the book now, it’s an American edition, which almost certainly means that it came from Compendium Books, a long-closed four story treasure trove of books in Camden that specialised in US imports.

He produced the version of White Rabbit that Grace Slick recorded with her band Great Society, before she joined Jefferson Airplane